< Previous | Contents | Next >

On a Roman Highway

Royston Manor in 1910.

Clayworth church, c.1910.

CLAYWORTH. It lies along a stretch of the Roman road from Doncaster to Lincoln, and its old church is a charming wayside picture of neat grey walls and roofs, timber-fronted porch, and a fine line of windows six centuries old. Near it the Hall shines golden through the trees; and down a lane, where flowers bedeck the cottage walls, is red-roofed Royston Manor, with mullioned windows looking across a wide expanse of fields. Much of the old house has gone, but it still has something left of the Elizabethan home of the Otters, who have lived here nearly all the time since it was built in Queen Elizabeth's day.

The upper part of the tower, with eight fine pinnacles and eight quaint gargoyles, has been rebuilt, but in the base is some of the oldest work in the church, coming from early in the 12th century, or even from Saxon days. Part of the wall between the nave and chancel is of the same time, and has a little herringbone masonry near the arch. There are two Norman doorways, one with a later one built outside it, the other framing a fine old door with studded panels and restored tracery.

The 13th century nave arcades of wide and elegant bays have pillars on Norman bases, one pillar with five heads and three ornaments in place of a capital, another wreathed with foliage. A 13th century archway in the south wall of the chancel opens to a chapel shut off from the aisle by a simple stone screen which may have been set up about 1388, a rare possession for a village church. A 13th and a 15th century archway lead from the chancel to the north chapel, which has a 700-year-old arch between it and the aisle.

The clerestory is 15th century. The charm of many of the 14th century windows is enhanced by modern glass, saints and prophets and angels making a fine gallery, others showing Christ giving the keys to Peter, the Annunciation, and the Wise Men. The tower has a Jesse window, and in the 19th century east window are scenes of Our Lord washing the feet of the Disciples, Peter leaving the Judgment Hall, Gethsemane with the soldiers sleeping,' and the Crucifixion. The upper half of the beautiful vaulted screen is new; the base, with its massive embattled rail enriched with floral medallions, is perhaps older than the Reformation. The new font has an old carved cover, and an old font has traces of painting.

The oldest memorial is a floorstone in the tower with a worn inscription to a rector of 1448. Under a great stone tomb carved with foliage and a shield of arms sleeps Humphrey Fitzwilliam, a Tudor judge, and on the tower wall is a memorial to William Sampson, a rector who founded a school and left behind 62 closely-written leaves of parchment giving a history of the parish from 1676 to 1701. Among the memorials of the Hartshornes who lived at Hayton Castle (now a farmhouse between the village and North Wheatley), is a quaint brass with the tiny figure of Time lying on his back; he has his scythe, and the sands are run down in the hourglass at his feet. The rhyme on the brass tells us of the virtues of John Hartshorne of 1678.

There are memorials in the church of a Yorkshire family distinguished in the siege of Scarborough Castle during the Civil War, the Ackloms. They had the neighbouring Wiseton estate in the time of Charles the Second, and.half a century ago built the handsome hall on the site of the older house in which they lived through the 18th century till the heiress married Lord Althorp, a well-known politician and an honest one. Lord Brougham was a frequent guest, and it has been said that perhaps the first Reform Bill was outlined under this roof. In the fine park is an old tulip tree and a magnificent fern-leaved beech.

Two brothers of the Otter family of Royston Manor are remembered in the church, and there is a wooden cross from the grave of one of them who fell in Flanders; the other was killed in an accident.

Proud Knights and Their Ladies

CLIFTON. Our countryside has few corners more beloved by those who know them, or more delightful for those who come upon them suddenly. Clifton, a mile or two from Nottingham, lives in poetry and in the hearts of all who come this way.

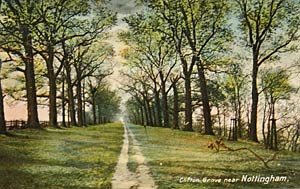

Clifton Grove, c.1910.

It is Nottingham's poet Henry Kirke White who has put it into literature in the dismal legend of the Fair Maid of Clifton, and in his liner poem on Clifton Grove, the far-famed view of oaks, elms, and beeches, planted two centuries ago and stretching for more than a mile along the top of a steep cliff overhanging the Trent, racing far below in one of its swiftest channels:

Dear native grove, where'er my devious track

To thee will memory lead the wanderer back.

Still, still to thee where'er my footsteps roam,

My heart shall point, and lead the wanderer home.

Other famous sights the village has. Who can forget the green on which every Mayday the children dance round the Maypole? Round it are gathered thatched cottages, gay gardens, the rectory, a pretty row of 18th century almshouses, and groups of stately trees; and on the green itself is a gabled dovecot lined with 2300 nests, a most remarkable number. It may be 18th century.

Clifton Hall, c.1880.

At the head of the famous Grove stands Clifton Hall, plain outside but packed with treasure. It has lovely gardens with flights of steps leading down from terraced lawns, and shaded by rows of yews. In the woods is a summerhouse two centuries old. But far older than the mellowed walls of the great house is the story of the Cliftons, who have known the village from medieval days and still live at the hall, though the last male of the line died in 1869. For centuries they have been figures at our courts and on our battlefields, and many of them have had their favourite name of Gervase. The first Sir Gervase was High Sheriff of Notts and Derbyshire. Queen Elizabeth called one of them Gervase the Gentle. Another Gervase, first baronet, born on the eve of the Armada and dying when London was burning, inherited the estates as a baby and grew up to marry seven wives. He offered a fortune to Charles Stuart when the king wrote for all the arms he could send, and was fined heavily at the end of the war for his loyalty; the king's letter is still kept at the hall. A portrait of this Sir Gervase hangs on the wall, and the story is told that he was much beloved for entertaining all who came his way, king or beggar.

In the hall is also a portrait of Sir Arthur Clifton, and near it is his uniform, with the banner of the regiment he commanded at Waterloo. He lived to be 99, and was uncle of the last baronet of the house, Sir Robert, who, having encumbered his estates in his youth by losses on the turf, opened the Clifton collieries in the hope of retrieving his fortunes. One of the greatest treasures here is Romney's painting of Frances Clifton, who in 1797 married Robert Markham, Archdeacon of York. Their son became rector of Clifton, built the rectory, and laid out its grounds.

Clifton church in 2004.

We meet some of the Cliftons in the church, where a wonderful array of monuments are links of brass and stone in their story. It is a beautiful building with a 14th and 15th century tower rising from the middle of a cross, and a lovely gable cross with a crucifix, over 400 years old, is on the west end of the nave. Like most of the church, the south arcade with finely carved capitals is 14th century, the clerestory coming from its close. The oldest part is the north arcade, with round pillars and pointed arches, built when the Norman style was passing.

Very charming is the effect of the lofty arches of the tower, framing a view of the much-restored 15th century chancel with its great windows and lovely roof. The roof was built in 1503 by a rector who signed it with his name and his quaint portrait. Under the brilliant east window is a splendid reredos of Derbyshire alabaster, coloured blue and gold. The stalls and screen are modern, and a fine chest is over 400 years old.

Most of the old monuments are in the north transept. The knight lying in an alabaster tomb with his head on a peacock, his feet on a weary lion, and the Clifton lion rampant on his surcoat, is either Sir Gervase, who died under Richard the Second, or Sir John, who fell at the Battle of Shrewsbury. The fine brass portrait of Sir Robert Clifton of 1478 shows him in armour with his head on a helmet and a greyhound at his feet; another brass is of his son Gervase, knighted at the coronation of Richard the Third. Very lovely is the smiling figure of his wife, Alice Nevill, who lies on an alabaster tomb, wearing a long-sleeved gown of smooth folds.

"Gervase the Gentle" lies magnificent with his two wives, all three in ruffs and wearing a remarkable number of rings, one wife having 11 and the other 8. On one side of the tomb are the five children of his first wife, and on the other is the second wife's son George, who was only 20 when he died a few months before his father, leaving the baby Gervase as the heir, who was to grow up to marry seven wives. We see George again in a brass portrait with the wife he married when he was only 14; he wears a short cloak and a big ruff, and she has a cap with her gown and embroidered petticoat. Close by is the floor-stone of Dame Thorold, the grandmother who cared for the baby heir.

Grown-up, the much-married Sir Gervase set up an elaborate monument to his first three wives in 1631, showing their arms on a black sarcophagus with a medley of bones and skulls below; and built a vault in which he buried six wives, the seventh outliving him. At his own death in 1666 his bust and the arms of all the wives were placed over the chancel doorway to the vault. He is said to have left a thousand pounds for his funeral, which was attended with great pomp and ceremony.

There are many later memorials to the Cliftons, and one more relic of old days is a leaden case thought to contain a heart, perhaps of Sir William Clifton, a crusader. They had a negro servant in the 17th century, and it is said the initials J. P. on the entrance to the porch mark his height of 6 feet 4 inches. A floorstone in the south transept covers his grave, and tells us that Joseph, commonly known as the Black Prince, was converted to the Christian faith and died in the hope of a better life.

A charming memory of Clifton is the peep over the churchyard wall to the grounds of the hall, with a glimpse through the trees of the river shining below.