< Previous | Contents | Next >

The Home of the Byrons

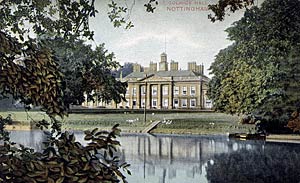

Colwick Hall, c.1905.

Colwick church, c.1905.

COLWICK. There is old and new Colwick. The old, with hall and church and park, has been drawn into Nottingham; the workaday part and the rambling old rectory by the Trent are left to the county. The herons still nest in Colwick Woods.

The hall and the church are close companions, with great beeches between them, but the great days of both are gone. One is a hotel, attached to the racecourse in Colwick Park, and the other we found in sorry plight, deserted for a mission church in the busy part of the village. Even before this book appears its monuments may be gone.

Built in 1776, and keeping still a splendid staircase and fine rooms with fireplaces in the style of the Adam brothers, the Hall is full of story, for the place where it stands is said to have been lived on since Saxon days. It was a home at the time of Domesday Book, when there was a mill by the Trent. Among the many owners who followed were the De Colwicks, who held it for a rent of 12 barbed arrows supplied to the king when he came to Nottingham Castle; then came the Byrons and the Musters, through whom it became the home of Mary Chaworth, the ill-fated heiress of Annesley immortalised in Byron's poems. She was his early love, but came here as the bride of the sporting squire, John Musters. She was here when the Reform Bill rioters looted and fired the hall, and the exposure she suffered then brought about her death a few months later at Wiverton Hall.

From the churchyard gate, a fine example of the ironwork for which Nottingham was then famous, we see the city's towers and spires, its castle high on a rock, the splendid dome of the new Council House, and the last of its old windmills at Sneinton. The church came into Domesday Book, but rebuilding by the Byrons in the 16th century and by the Musters in the 17th left it with little interest except for the monuments in a chancel almost too dark for them to be seen.

The Byrons were at Colwick for nearly 300 years, and there are monuments of three generations here. On an altar tomb are the elaborately engraved figures of Sir John Byron of 1576 and his two wives. Sir John, a knight in armour, was a favourite of Henry the Eighth, who granted him Newstead Priory in 1540. He was known as Little Sir John of the great beard, and, though he has no beard on the top of his tomb, he has one on the front, where we see him with his sons. With this group are three daughters and their mother, all in ruffs.

The monument to Sir John Byron and his wife, Alicia, daughter of Sir Nicholas Strelley, Knight, of Strelley. Sir John died in 1609.

The fine alabaster figures of his son (Sir John of 1609) and his wife Alice Strelley lie under the pillared canopy of a great monument across the chancel. The knight is in armour, wearing ruffs and a triple chain, and has an extraordinary moustache and a very long beard. His lady has a ruff and a double chain round her neck. Their son, another Sir John, is kneeling with his wife on a wall monument, both having died on the same day in 1623, and below them kneel their son and a granddaughter.

Among the Musters memorials is a bust of Sir John de Monasteries of 1680, who repaired the church. An elaborate monument has the absurdly theatrical figures of his son and his wife in robes and sandals kneeling lifesize on a projecting tomb. At one side of the altar stands (or stood when we called) the draped figure of Mary Ann Chaworth-Musters, Byron's Mary of Annesley. At the other side sits Sophia Musters of 1819, with three children at the foot of the monument, one dancing, one with a harp, and one with a board and easel. This accomplished lady painted the unusual east window, glowing with golden light below grey clouds, showing a dove looking down on Unica with the lion, the Flight into Egypt, and figures representing Justice, Faith, Hope, and Charity. She took for her inspiration the window designed by Sir Joshua Reynolds in the Chapel of New College, Oxford.

An odd thing we found in the church was a thankoffering for the coming back of the Stuarts, a dado in the nave of 31 carved oak panels, and five larger panels in the chancel, brought from Colwick Hall in 1661 by Sir John Musters. Worn and shabby with time, they were destined to be removed to Annesley Hall. This sad church may perhaps be pulled down when a new one is built, and the Byron monuments are to find a home in the crypt at Newstead Abbey.