< Previous | Contents | Next >

King Charles's Rules

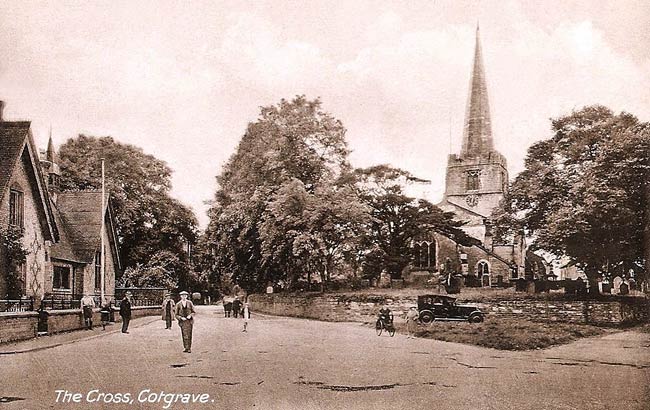

Cotgrave in the 1930s.

COTGRAVE. Reached by pleasant lanes in a countryside of fields and copse and cover, near the Fosse Way, it gathers trimly round its little square. Its prettiest corner is in a leafy lane where great limes and elms guard the church, and a lychgate leads to a burial-ground.

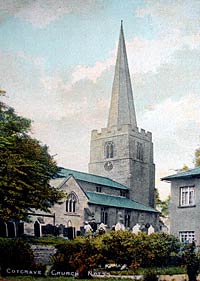

Cotgrave church, c.1905.

A gnarled old walnut tree stands near the tower, and an ancient yew shelters the chancel. Like most of the old work left in the church, both tower and spire come from the 14th century, the tower buttressed to the battlements and opening to the nave by a lofty arch. Of about the same time are the nave arcades with clustered pillars, and the chancel arch whose sides and capitals come from the close of Norman days.

An oak panel has the names of men who fell in the Great War, and of five women among those who served. We read in the tower that the bells were rung for an hour and 20 minutes, half muffled, in memory of Dorothy White, who died in 1918. Cotgrave has always been proud of its peal of bells, and she was one of the ringers. Another inscription tells that they were rung for over three hours in 1927 in memory of Pryce Taylor, one of the bell-founders of Loughborough, who died in Canada. Under the tower hang King Charles's Rules:

Profane no Divine Ordinance

Touch no State matters

Urge no Healths

Pick no quarrels

Maintain no ill opinions

Encourage no vice

Repeat no old grievances

Reveal no secrets

Make no comparisons

Keep no bad company

Make no long meals

Lay no wagers

Do nothing in anger

Cotgrave finds its way into many parts of the country with marl for cricket pitches; it is found in a pit here.

For the White Rose

COTHAM. It overlooks the lovely vale of Belvoir from its place between the River Devon and the Lincolnshire border, and has a reminder of its story in a lonely church across a field.

The modest home of only a few folk, it has little claim to distinction now, but it was a proud village five centuries ago when it became the seat of the Markhams. William was Lord Treasurer of Edward the First, and in the church of East Markham, the village from which they sprang, lies the Judge Markham who drew up the document for deposing Richard the Second. Sir Robert, a supporter of the White Rose, was knighted after the battle of Towton Field, and his son John, set out from his home here to distinguish himself as a leader in the terrible battle when the White Rose met the Red for the last time at East Stoke, three miles away.

Cotham church in 2008.

© Copyright Richard Croft and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

No trace of their splendid house is left, but in the ivied church near which it stood we see Anne Warburton kneeling with three sons and four daughters under the canopy of a wall monument; she was the wife of Robert Markham, whose unthriftiness brought to an end the glory of his house in the last years of Queen Elizabeth.

The church is only a shadow of its old self. Towards the end of the 18th century it lost two aisles as well as its tower, from which two gargoyles now guarding the churchyard gate are said to have looked down for over 500 years. Some of the old aisle windows are in the nave walls, and two 14th century relics are the massive font and the charming piscina. Two marble tombs, one of which has lost its brass portrait of a 14th century knight, may belong to the Leekes, who lived here before the Markhams came.

Cottam church (now a private residence) in 2012.

© Copyright Jonathan Thacker and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

COTTAM. Its few houses line one side of the road and look over meadows stretching nearly a mile to the Trent, dividing Notts from Lincolnshire; and its tiny church, guarding a precious doorway of 800 years, hides from all who hurry by.

A lychgate at the end of a wayside path brings us to the simple building, with walls aslant, nave and chancel under one steep roof on four massive old beams, and a turret for one bell. A porch shelters the Norman doorway, which has crude chevron mouldings boldly carved, and pillars on each side with scalloped capitals. The bowl of the ancient font is outside the porch, set on a new base.

A Gem From Pin Hole Cave

CRESWELL CRAGS. They belong to Derbyshire as well as Notts, the boundary running through them on the verge of Welbeck Park. At their foot are the famous caves where remarkable treasures made by the earliest men in Britain have been found. These caves have names of their own, Robin Hood's Cave, Church Hole (named from its narrow tapering entrance), Mother Grundy's Parlour, and the Pin Hole.

Nearly 50 years ago Sir William Boyd Dawkins began to dig in these caves, and among many treasures he found the earliest example of pictorial art discovered in our land, a piece of smooth bone three inches long and an inch deep, on which had been scratched the head and shoulders of a horse. The mane of the horse is remarkable; the hair stands up straight.

Inch by inch the soil from the first three of these caves was removed and sifted, down to the white sand in which there were no remains. Above the white sand and red sand were bones, and one or two rude implements of quartzite which were also found in a layer of red clay above. The remarkable thing about these bones is that they belonged to the hippopotamus and the rhinoceros, animals which needed a far warmer climate than ours. Hyenas shared the cave with them, the marks of their teeth being on the larger bones. The hippopotamus is a survivor of the Pliocene into the early Pleistocene age, and the man who made these quartzite implements before the ice ages descended on the land must have had a hot meal from the flesh of these beasts, for signs of fire remain on the bones.

Above the clay we come to the mottled and light-coloured cave earth with implements in a higher stage of manufacture. The hare was the chief food of these men. On a higher layer still is a red cave-earth in which charcoal fragments and blocks of limestone occur with the bones, with implements made of flint brought from a distance. The men who made these were the artists, and used implements of bone as well as of flint. The top layer of all consisted of stalagmite material and other worked flints. Most of these objects are at the British Museum.

A few years ago Mr Leslie Armstrong decided to excavate Pin Hole Cave, which had been left as not worth troubling about. It has proved the richest of all, and from it we have evidence that at least two glacial periods have passed over Creswell Crags, driving men from it. Thousands of years separate the periods of its habitation.

The gem of Pin Hole was an engraving of a masked man or woman on the bone of a reindeer. The figure is standing erect, apparently engaged in ceremonial dancing of the kind Australian or African natives enjoy today. Other engravings worked on ivory, and the beautiful flint tools with which they worked and hunted and fished 20,000 years before the birth of Christ, were found in the upper layer of this cave, which has proved one of the most valuable records we have of the men of the Old Stone Age over a period of nearly a thousand centuries.