< Previous | Contents | Next >

The Stately Homes

DUKERIES. All travellers in Notts come to the Dukeries, one of the loveliest patches of our Motherland, and one of the richest in associations, for this remnant of old Sherwood Forest has become the glorious domain of the three rich estates of Welbeck, Clumber, and Thoresby. Their spacious deer parks, woodlands, gardens, and lakes cover the greater part of a rough seven-mile square, divided almost in two by the highway from Ollerton to Worksop, and threaded by other roads where we may ride, and paths where we may walk among the hoary oaks, the stately beeches, and the countless silver birches. None of the old trees make a braver array than those at Bilhagh and Birklands, which are on each side of the road as we go from Edwinstowe to seek the Major Oak.

The River Poulter fills a string of lakes as it flows through the parks of Welbeck and Clumber; the River Meden forms Thoresby's beautiful lake. Rufford Abbey at the south-east, and Worksop Manor at the north-west, are worthy neighbours of the three lordly estates of the Dukeries, owned by the Duke of Portland, the Duke of Newcastle, and Earl Manvers.

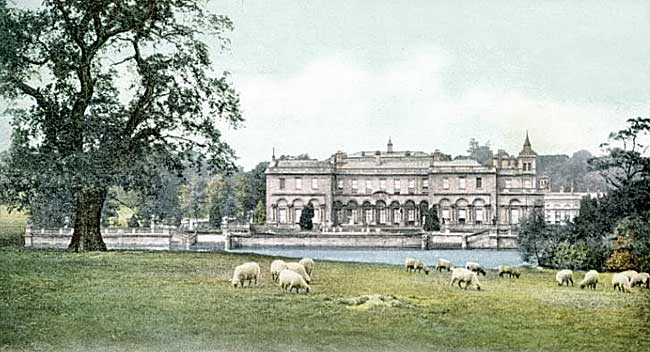

Welbeck Abbey, c. 1905.

Welbeck Abbey is an imposing pile, reflecting the changing taste of its owners through three centuries, for there is little left of its earliest days, when it was actually an abbey. It was founded in the middle of the 12th century by Thomas de Cuckney, and was the head of the Order till the destruction of the monasteries by Henry the Eighth, when it was granted to Richard Whalley. He became involved in the troubles of his relative the Duke of Somerset, was imprisoned, and so heavily fined that he had to part with Welbeck. Bess of Hardwick bought the estate and left it to her son Sir Charles Cavendish, whose son Sir William was made Duke of Newcastle for his services to Charles Stuart. It was he who built the old riding-school at the abbey. His wife idolised him and wrote much in his praise, thus earning the contempt of Pepys; she also wrote poems and plays.

Welbeck passed into the hands of the Earl of Clare, and the Earl of Oxford whose daughter was the "noble, lovely little Peggy" of Matthew Prior's poem. It was she who brought Welbeck to the Bentincks by her marriage with the second Duke of Portland.

The house is built round the 13th century vaulted undercroft of the abbey's western cloister range, part of which is now the servant's hall. Most of the central block was built by Sir Charles Cavendish early in the 17th century, and the south wing, originally built by his son (the first Duke of Newcastle) about 1630, was rebuilt by Lady Oxford between 1740 and 1750. The whole building was much altered by Sir Ernest George after a fire in 1900.

The west front has embattled parapets and a great square tower from which the duke may display his banners. The east front rises from a broad terrace over the lawns to the lake. The south front, with balustraded parapets, is in that Italian style which during the 18th century changed the appearance of so many English homes.

There is another aspect of it less visible and in some way more remarkable, the underground Welbeck. The ceremonial way to the abbey is through the iron gates of the Lady Bolsover Drive, but once it was through a mile-and-a-half tunnel under the lake, lighted artificially and by skylights in the roof. It was wide enough for a horse and cart then, and is wide enough for a motor-car now. This is only one of the labyrinth of underground tunnels and rooms dug to the order of the fifth duke, who employed thousands of men and spent colossal sums of money on these undertakings. He was a recluse, and because of his unusual style of building was generally regarded as extremely eccentric. One of these underground chambers is a vast place, 160 feet long and 63 wide, and it is now used as a picture gallery and ballroom. It is the biggest room in England without pillars. The duke also built a great riding-school, 400 feet long and 106 wide, with a roof in three divisions supported on fifty pillars; the centre division, of iron and glass, is arched and decorated with a frieze of animals, birds, and foliage.

In the remarkable ballroom are paintings of members of the great families with whom the Bentincks claimed connection by marriage: Cavendishes, Holies, Talbots, Harleys, Veres and Wriothesleys. This wonderful collection of portraits is like the pedigree of the Dukes of Portland. Notable among these is the series of portraits of the Wriothesleys, Earls of Southampton, formerly at Titchfield Abbey in Hampshire. Also in the ballroom is a drawing of an angel by Sir Joshua Reynolds, bequeathed by the artist to the third Duke of Portland.

The dining-room is remarkable for the fine Van Dyck portraits of Prince Charles, William Cavendish (Earl of Newcastle), and the famous Earl of Strafford. The Gothic Hall, built in the middle of the 18th century by the Countess of Oxford, has splendid fan-vaulting, and the drawing-rooms are notable for their exquisite decoration and French furniture. The library and chapel were built as a riding-school by the first Duke of Newcastle before his fortune was sacrificed to the Stuarts. Things beyond price in the library are the collections of letters written to the Portlands through many reigns, beginning with the letters of William the Third (in his own hand) to William Bentinck, companion of his boyhood, advisor of his manhood, and faithful soul for whom he sent on his deathbed. Here also is preserved the Harley correspondence retained by Lady Oxford when the Harleian manuscripts were sold to the nation in 1753, the enormous correspondence of Robert Harley, first Earl of Oxford, and Lord Treasurer.

These are some of the heirlooms of a family prominent in English affairs since the days of the Stuarts, but there are others of a different kind, including a collection of beautiful miniatures, the pearl earring worn by Charles Stuart on the scaffold, the chalice of his last Communion, a rosary of Henrietta Maria, the emerald seal of Charles the first, a ruby ring Dutch William gave to his Queen Mary (worn at her coronation), and a dagger of the insatiable Henry the Eighth.

The gardens of Welbeck are most beautiful, massed with flowering borders, a triumph of modern gardening; there are vineries, conservatories, and orangeries. One of the famous oaks in the park is the Greendale Oak, past its old glory but still with the archway cut through its trunk in 1724 by the second Earl of Oxford. One of the treasures of the furniture in the abbey is a cabinet made of oak from this tree, with many panels showing it as it stood in its greater days. Near the lakes, which wind for over four miles, is a bronze medallion in memory of Lord George Bentinck, son of the fourth Duke, who was famous at the time of the Corn Law agitation and died here suddenly when walking to Thoresby.

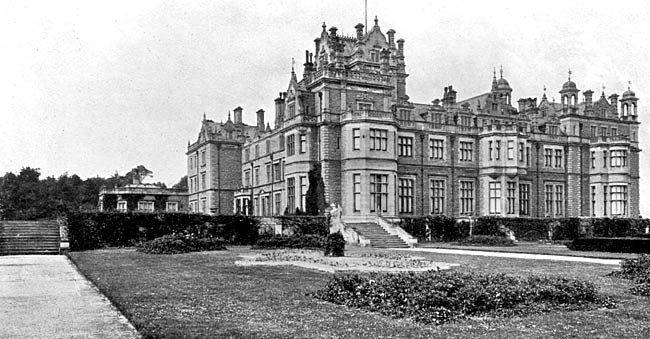

Clumber House. c.1910.

Clumber Park is eleven miles round, and through it runs the noble Duke's Drive, an avenue three miles long, with a double row of limes on each side. It was a barren waste and a rabbit warren till about 1770, when the Duke of Newcastle built Clumber House. It had four wings round a central block, and was designed by Stephen Wright, who was responsible for the old Cambridge University Library. Fires last century and this left old work only in the wings. The library, state drawing-room, and great hall all had their glories, but a sad day came for them a few years ago when the house became a shell emptied of its rich store of treasure, and the charming church with a delicate spire, built half a century ago, was closed. Worse was yet to come, for in our time the splendid house was demolished. But the church and the beautiful Lincoln Terrace (built of stone brought from Italy a century ago) are still mirrored in the lake of nearly a hundred acres. The rare collection of famous pictures has been sold.

Thoresby Hall, c.1910.

Thoresby Park, formed in 1683 by the Duke of Kingston, is the most richly wooded of the ducal estates. Bounding it on the south is Bilhagh (entered by the quaint gates crowned by two stone deer), with its ancient oaks from medieval days, and the glorious Ollerton beeches, which form a forest cathedral unsurpassed. It may be doubted if there is in England a more impressive natural nave than this. On the west of Bilhagh are the Birklands, renowned for their slender silver birches.

The splendid house stands near the lake of about 65 acres, and a road running east through the park from Budby passes near by. It was built about 1870, near the site of a brick mansion which followed an older house burned down in 1745. It was in the older house that Lady Mary Montagu passed her girlhood years with her father.

The chief rooms of the house we see have decorated ceilings and floors and panelling of oak, walnut, of maple. There are fine carved mantelpieces in white marble, and the library chimneypiece shows a scene in Sherwood Forest. It is the home of Earl Manvers, whose family name is an honoured one in the county, for there have been Pierreponts in Notts from very early days.