< Previous | Contents | Next >

The Biggest Oak

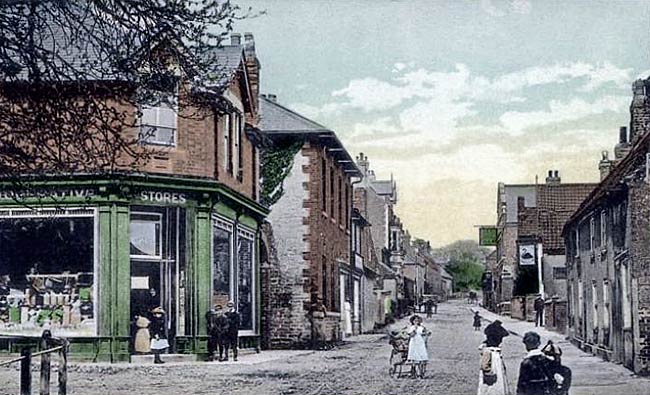

High Street, Edwinstowe, c.1905.

EDWINSTOWE. Pleasantly set on the River Maun, it is a gateway to some of the loveliest haunts of old Sherwood Forest. Above the church and the charming hall the village opens out to a spacious common on the doorstep of Birklands and Bilhagh, two parts of a wonderful stretch of forest with a driving road between, and many a path which we may tread in the wake of Robin Hood and his Merry Men. Birklands has ancient glades and a wealth of oaks, beeches, and the graceful silver birches which give it its name; Bilhagh has the grandest remnants of the old Forest, with magnificent oaks which have seen medieval and probably even Norman days, splendid still whether in life or in decay. It is on record that in 1609 there were 21,000 oaks in Birklands and 28,900 in Bilhagh, as well as thousands of other trees.

The Major Oak in 2010.

Within a mile of the church is the Queen or Major Oak, an ancient tree of great renown; it is the glory of Birklands and perhaps the biggest oak in the land. No one knows how many years it has weathered, but it is hale and green and shapely yet in spite of having lost its top in a storm last century. Standing in a little clearing, with oaks and silver birches paying it homage at respectful distance, this Monarch of the Forest has a hollow trunk 30 feet round, strong enough to support unaided the mighty limbs which make a ring of about 260 feet. The branches are held together by a ton of iron bands, and are protected from the weather by 15 cwts. of lead.

A mile and a half west of the Major Oak is Robin Hood's Larder, the remnant of another great oak in which Robin is said to have hung his game. The shell of three-quarters of its hollow trunk is left, 24 feet round, still giving life to the green above. Near this tree, where the ways through the Forest divide, is a charming one-storeyed Russian cottage in a delightful setting of lawn and flowers and rambler roses, backed by beech, birch, and chestnut trees. It is built of dove-tailed logs, adorned with splendid carving. The shutters are panelled and carved; the ridge of the steep tiled roof, the barge-boards and the decorative medallions are all like open embroidery. Made in Russia, and shown at a great Exhibition in England last century, it stands by the road for all to see, a gem worth finding.

On the edge of Birklands, set back from the Ollerton-to-Mansfield road, a tall iron cross painted white marks the site of a royal chapel, chantry, and hermitage dedicated to Edwin, King of Northumbria. A heap of old stones piled round the base of the cross is all that is left of the chapel where King John paid the hermit to pray for his soul.

Story says that the village itself owes its name to the Christian King Edwin, whose body perhaps had temporary burial here after he was slain in battle by Penda thirteen centuries ago. It was afterwards carried to Whitby for burial in the abbey between the moors and the sea.

Edwinstowe church in 2010.

The tradition of the Forest clings to the church, for here Robin Hood is said to have made Maid Marian his bride. Beautiful inside and out, looking younger than its years with restoration, its stone walls are of rosy hue with many delicate tints here and there. It came into Domesday Book, but has nothing older than the plain Norman priest's doorway in the chancel.

The lovely tower, over 700 years old, is a landmark with its stout broach spire adorned with fine pinnacles and windows between them. The spire was much rebuilt about 1680 after a storm, and at the same time the people petitioned the king for leave to cut enough of the forest oaks to pay for repair to the rest of the church. Two extraordinary heads, one with great staring eyes and the other with open mouth, are on the tower arch. Among the heads on the 13th century north arcade and the 14th century south arcade are mitred bishops, a pouting face, some with curly hair, and one with smartly trimmed beard.

Most of the windows are medieval, one having a little old glass, and the clerestory is 500 years old. A window with Gabriel, Michael, and Raphael is in memory of somebody from Kent who died on a New Year's Eve. The fine font with quatrefoils is 14th century. A piscina in the south aisle is of this time, and two aumbries here have floors formed by the two halves of a 700-year-old coffin lid engraved with shears by the stem of a cross. The medieval stone altar, with two crosses, has been set up after being found on the floor of the belfry. Fragments of the old chancel screen are in the organ case and over the altar. The altar table is Jacobean, and under glass on a pillar is a Cavalier's spur found in or near the church. A dwarf pillar piscina, only 16 inches high, has a four-clustered pillar between its head and base; it is 13th century.

An unusual relic is a stone, about 14 inches long, projecting from the north aisle wall, carved along the middle with a kind of milling pattern. It is possible it may have been used for measuring land, and to have been originally 18 inches long, which was the length of a forest foot.

A stone marks the grave in the churchyard of Dr Cobham Brewer, who, while living with his daughter, died at the vicarage here in 1897. A great scholar, he is remembered for his Dictionary of Phrase and Fable and his Reader's Handbook to Literature, two volumes still used by working journalists. A stone telling us that a native of Scotland lies here has a touch of the Scotsman's love of the land from which he comes away.

The Screen of Many Colours

Egmanton church in 2002.

EGMANTON. It lies in a hollow with orchards and trees, the pretty gardens of some of its houses reached by tiny bridges spanning a wayside stream. It has a fine little church with something of Norman days, and memories of a castle built soon after the Conquest. It stood on the green mound near the church, encircled by a dry moat and known as Gaddick Hill.

The church is by the great chestnuts overhanging the road in company with shapely old yews. The arresting thing about the interior is its medieval air, which comes chiefly from the red, white, blue, green, and gold of the modern oak screen, the organ case over the doorway, and the open pulpit—a most unusual blaze of colour for a church in this countryside. The handsome screen with entrance gates has beautiful craftsmanship in its tracery and fan-vaulting, and has a star-spangled canopy curving above a Crucifixion group on the roodloft.

We come into the nave by a Norman doorway on which are small crosses which may have been made by pilgrims. The panelled door is old. The nave arcade has the English pointed arches on the round Norman pillars, and the chancel arch, with a face at each side, comes from the same builders, the men who saw the Norman style changing into English. Most of the windows are medieval, old glass showing roundels with wreaths and part of a bird, a glowing little figure of St George, and perhaps St Michael. The massive Norman font has a beautiful modern cover carved with symbols, the rebuilt chancel has a 13th century piscina with two arches, and the 13th century Savile chapel has a charming trefoiled piscina and an aumbry. The old almsbox was made from a solid block of wood, the nave roof has old beams, and there is a Jacobean table.

A stone in the sanctuary floor has on it worn portraits of Nicholas Powtrell and two wives who lived at Egmanton Hall in the time of Queen Elizabeth; nothing is left of it now. Gargoyles of quaint heads, a muzzled bear, and a grotesque with its hands in its mouth look down from the tower.