< Previous | Contents | Next >

The Wonderful Panorama

High Street, Gringley-on-the-Hill, c.1910.

GRINGLEY-ON-THE-HILL. Halfway between Bawtry and Gainsborough is this airy village of lovely views and steep and dangerous ways. It climbs the hillside and spreads along a ridge at the end of a long range of low hills which stretch from Nottingham; and in Beacon Hill, a green mound at the very end of the ridge, Gringley finds its glory.

From this site of an ancient encampment, where Prince Rupert is said to have camped before riding to the relief of Newark, is a matchless panorama reaching for 20 or 30 miles whichever way we turn. We see the gleaming towers of Lincoln, the Great North Road riding straight through the land beyond the valley of the River Idle, and the Cars which carry the eye to Yorkshire, a flat area like a great sea of reclaimed fenland, but a beautiful sight from Beacon Hill when the sun lights up the golden corn and shadows make waves on the fields.

Gringley-on-the-Hill church, c.1910.

Strikingly set where the road divides to make a dangerous bend and a steep drop, is the fine old village cross, and near it, standing well above the road, is the church, which has been restored this century from a pitiable plight to be a bright place not ashamed of its years. The tower, with battlements and pinnacles which were all in a heap inside it till the restoration, is mainly 15th century, though a built-up arch in the outside north wall may be Norman. Against this wall is an ancient stone coffin. From the 13th century comes an arch to the chancel chapel and the north arcade of the nave, its leaning pillars on massive bases. Among many medieval windows are those of the 15th century clerestory, and the east window of the new south aisle, with glass in memory of men who died or served for peace; it shows St George with the dragon, St Michael with scales and flaming sword, and Christ crowned.

A treasure of the church is a beautiful shaft piscina 600 years old, with natural foliage encircling the top of a round column. Some old timbers remain in the roofs of the nave and the north aisle, and of four old bosses in the nave one shows the grotesque head of an animal with its tongue out, and another a man's face with a great moustache and a small beard. A quaint face with pursed lips and goggle eyes looks tirelessly out from the wall over the small doorway in the tower. The modern screens are neat and good, and a charming little angel crowns the modern cover of the font.

The Tapestry Map

GROVE. Right well is it named, for this secluded hillside village is truly mantled in trees.

Above a delightful gathering of red cottages, white-walled farm, rectory, and church, where the road becomes a deep cutting at the top of the village, two flights of rough-hewn steps climb to a tall grey cross with a fine view of the countryside and a sight of Lincoln Cathedral when the day is clear. The cross is a tribute to men who went to the war, and a memorial to one who did not return.

Grove church in 2014.

© Copyright Alan Murray-Rust and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

A lychgate with stout oak timbers opens to the pretty churchyard, where the small aisleless church was built in 1882 in the style of 600 years ago. Its fine tower has a spire with two tiers of tiny dormers, and is very neat inside with its vaulted stone roof and a charming arch to the nave. There is rich carving in the font, and also on a niche on the porch, sheltering a crowned figure of St Helena.

The only relics of the old church, which stood close by, are two floorstones in the tower, one showing a chalice by the stem of a cross, the other with splendid portraits of Hugh Hercy of 1455 and his wife Elizabeth, restored by a descendant. Hugh is a knight in armour with sword and dagger, with a tam o' shanter kind of hat on his head, and his feet on a dog. His lady has a long pleated gown and a headdress at a rakish angle.

Grove Hall, c.1900.

The Hercys built the hall in the 16th century, but it is much changed since their day. It stands west of the church, hidden from the road in a park of rolling turf and fine old trees, and looking out to the dark woods of Sherwood Forest and the hills of Derbyshire. It still has some remains of the time of Henry the Eighth, and with the fine pictures and rare books treasured by the Harcourt Vernons, who live here now, are two unique tapestries worked by their kinswoman Mary Eyre 300 years ago. They make a complete map of Notts, with every place named.

North of the village, on Castle Hill, are traces of earthworks of Roman or perhaps earlier times, and a moat on the edge of the woods.

The Tribute of a Refugee

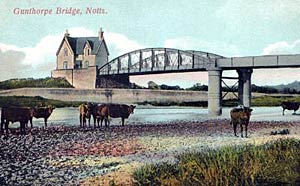

Gunthorpe Bridge, c.1910.

GUNTHORPE. Once owned by Simon de Montfort, it finds its beauty by a wide peaceful reach of the Trent where the river sweeps on its way to Hoveringham. Opposite Gunthorpe's quiet meadows are woods and cliffs crowned by the pretty village of East Bridgford.

Once there was but a ferry boat bringing the two villages together, but in 1875 Gunthorpe found a new importance, for with the building of an iron toll bridge (the first and only road bridge between Nottingham and Newark) all kinds of traffic began to pass along the river bank and down the village street. Half a century later came another change, and quieter days again for the heart of the village, and today the old toll house, bereft of its bridge, looks upstream to where growing traffic between north and south runs over the three wide spans of a fine new bridge.

In the little stone chapel of 1849, with just a nave and chancel and a bell in a gable, is Gunthorpe's roll of honour, the names of 58 men of whom 12 did not come back. They are set in a frame showing the arms of the Allies, the fine handiwork and gift of a Belgian refugee who lived here for a while, an architect of Ghent.

The Bell of a Thousand Years

Halam church in 2014.

© Copyright J.Hannan-Briggs and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

HALAM. Pleasant with its orchards and a stream flowing to the River Greet, sheltered by the low hills between it and Southwell, it is rung to church every Sunday by a bell known in the countryside as the bell of a thousand years. It hangs in a sturdy 13th century tower with pinnacles and a squat pyramid roof, a muzzled bear and a dragon among its gargoyles, and an arch all askew opening to the nave. The bell is said to be Norman and is still sound, though its 18th century companion is cracked and never struck.

The fine Norman chancel arch has scalloped capitals enriched with Vandyke and diamond pattern. The font comes from the close of the 12th century; the beautiful little nave arcade from the end of the 13th was opened out when the aisle was made new half a century ago. A projecting piscina rests on a carved head, and there is a handsomely carved Elizabethan altar table. The oak lectern of our century has a splendid St Michael in a niche.

We see the patron saint again in a 13th century lancet. Four lovely panels in other windows, by William Morris and Burne-Jones, show Gabriel bringing the good news, the meeting of Elizabeth and Mary, the Transfiguration, and the Ascension. A window rather like a page in a child's picture book has the Nativity with a choir of angels, roses and passion flowers climbing round the stable at Bethlehem with the oxen, an ass, and a lamb standing by, a dovecot and the doves, shepherds with an English sheep dog, and a shepherd with his crook. Four charming 15th century panels shining in a chancel window have Eve spinning, Adam digging, St Christopher carrying the Child, and St Anthony with his staff; birds are in the borders. On this window outside are two laughing faces, and on the north wall is a whistling boy.