< Previous | Contents | Next >

Schools and Scholars

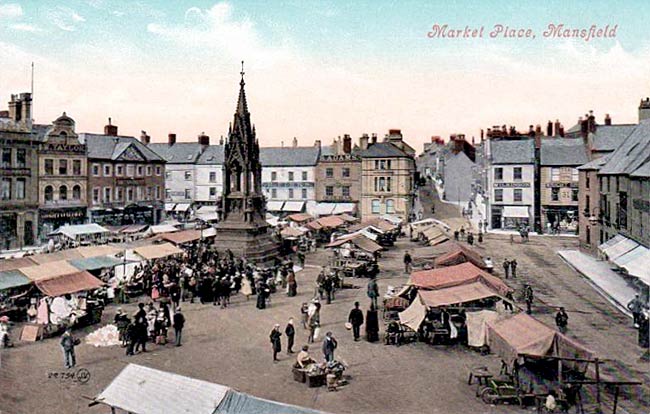

The Market Place, Mansfield, c.1910.

Church Street, Mansfield, in 2004.

MANSFIELD. This market town of about 45,000 people, busy with industries and mining, takes its name perhaps from the little River Maun flowing through it. It has a roll-call of notable men of which many a bigger place might well be proud, and though there is little that is old in its streets, Sherwood Forest is near enough to lend it some of the glamour of days gone by.

There are old cave dwellings at Rock Hill. The Romans are said to have encamped here, and coins of Vespasian, Constantine, and Marcus Aurelius have been found. It was a residence of Mercian kings, and was for centuries a royal manor, Norman and later kings finding it a pleasant resort when hunting in the Forest.

It has great civic pride, and its mayor wears a chain worth £2000. It has a link with London and the very heart of the Empire, for stone from its quarries is in the Houses of Parliament. In the marketplace is a great stone monument with a canopied turret, elaborate with lions and heraldry, in memory of Lord George Bentinck, who died suddenly in 1848 when walking in Sherwood Forest. Disraeli wrote his biography.

Mansfield is proud of its schools. Brunt's School has modern buildings now, and is endowed partly by the bequest of Samuel Brunt of 1709, and partly by Charles Thompson, who was born here and became rich in his business career in Europe and the East. He settled down here after seeing Lisbon destroyed by earthquake in 1755, and became a local celebrity; and he has been sleeping since 1784 on a hilltop a mile away on the road to Southwell, a spot he chose himself because it reminded him of the place from where he witnessed one of the most appalling spectacles in history. He lies with trees about his grave in a stone-walled enclosure.

The scholars of Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School have a fine modern building on a new site, but the 16th century one still stands in St Peter's churchyard. A tablet over the doorway tells of its foundation in 1561, and it has links with not a few of the men Mansfield delights to honour. Two of its boys became bishops and another was the Earl of Chesterfield who wrote the famous letters to his son. One boy who trudged to this school was Richard Sterne Archbishop of York and grandfather of the Laurence Sterne who gave us Tristram Shandy. Richard was one of Laud's chaplains and attended him on the scaffold. He founded four scholarships at Cambridge and two for natives of York and Mansfield, sometimes held by boys from his old school. He sleeps in York Minster.

The Archbishop was a son of Mansfield, as were also Hayman Rooke, the antiquary who greatly loved his own corner of Notts; James Collinson, the artist who was a fellow student with Rosetti and Holman Hunt; and James Murray, inventor of the circular saw, whose father was "old Joe Murray," Lord Byron's servant. An old friar and a young footman are among Mansfield's most distinguished sons. The friar was William de Mansfield, famed in the 14th century for his knowledge of logic, ethics, and physics; the footman was Robert Dodsley who made a name as poet, publisher, and bookseller. Born in 1703, son of a master of the grammar school, he was apprenticed to a stocking weaver, but ran away to London and took a post as footman. While thus engaged he wrote a book of poems and a friend of Pope took him into his service. Later he started a bookshop and publishing business. A very delightful man, Dodsley was as modest as he was popular. Tristram Shandy and Young's Night Thoughts were two of the books he published. Dr Johnson called him Doddy, and Doddy suggested to the Doctor the scheme of an English Dictionary. The Annual Register owes its origin to him.

George Whitefield came here to preach, and George Fox spent the first four years of his mission work in the neighbourhood; he was imprisoned here for interrupting service in the church. In the cemetery on the edge of the town lies William Whysall, who played brilliant cricket for Notts and for England, and was bowled out of life in 1930. A tall granite cross marks his grave, and on a granite shield are carved a bat and a ball, and a wicket with one bail off.

Mansfield parish church in 2004.

The only old church among a number of modern ones is the parish church of St Peter, standing in the middle of the town on a site where one of Mansfield's two churches may have stood when Domesday Book was made. The outside is embattled, the inside spacious and pleasing. The two lower stages of the tower come from the end of the 11th century, and a wide Norman arch opens to the nave; the top stage is 14th century, and the short spire with dormers is 1669. There seems to have been an earlier wooden spire covered with lead, for the repair of which the steward of the manor gave eight trees in Elizabeth's time. There is a fragment of Norman zigzag in a wall.

From a rebuilding of the church when the 13th century style was passing to the 14th come the lofty nave arcades and the chancel arch. The chancel chapels are 15th century, and the clerestory is about 1500.

In each of the two porches are two big and two small tapering coffin stones, all engraved with crosses. Against the wall of the south chapel is a great stone with remains of a Norman inscription, and the figure of a priest under a canopy; he was perhaps Henry de Mansfield, a 14th century vicar. In a recess of the south aisle a 14th century civilian lies sculptured in stone, wearing a long-sleeved gown, belted and buttoned. He has clear features and flowing hair, angels support his head, and his praying hands are broken. He may belong to the Pierrepont family. One of many brass tablets is to Johannes Farrer of 1716, the Latin inscription telling us that he was skilful, prudent, and faithful. Another is to John Firth, vicar here for 45 years of the 17th century. He was followed by George Mompesson, son of the heroic William Mompesson who won immortality at Eyam during the Plague.

Standing in a fine situation just outside the town, at Harlow Wood, is a splendid modern hospital for cripples.