< Previous | Contents | Next >

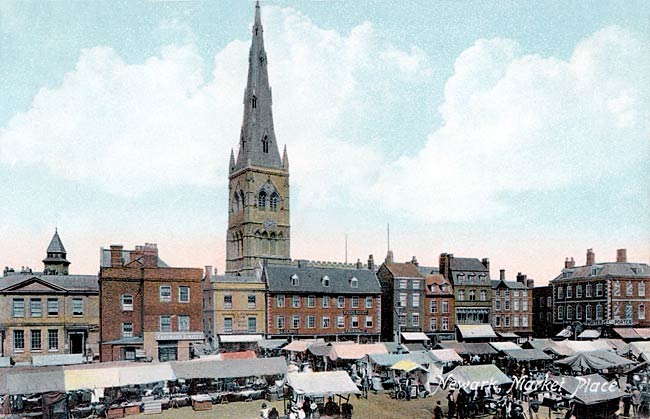

Newark market square and parish church, c.1910.

View of the church from Kirkgate, c.1910.

The marketplace has still visible the stone to which bulls were fastened in the days of bull-baiting. Surmounting the town hall front are figure of Justice, a lion, and a unicorn. Rising behind another side of the market square are the tower and spire of the old parish church, second to none in the county. Beautiful indeed is this spire, climbing 252 feet (as high as the church is long) and making a charming end to a view along the narrow Kirk Gate.

There was a Saxon church here, and of the Norman church which followed there remain the vaulted crypt below the sanctuary and the piers of the central crossing, perhaps meant to support a tower which was never built. The lower part of the west tower is 13th century; the rest of it, and the spire, are early 14th, the time of the south aisle of the nave, with beautiful tracery in its great windows and fine heads on the hoods. After the Black Death there was a long pause in the building; the nave, the north aisle, and the chancel are 15th century, and the transepts were added in 1539. Thomas Mering's chantry chapel was founded in 1500; Robert Markham's is six years later, with a small peephole, and with paintings on two stone panels representing the Dance of Death. One painting shows a young man gaily dressed, a feather in his cap; the other is his lordly skeleton, holding a rose.

Newark parish church from the south-east in 2005.

Looking at the church outside, we do not know whether to be more astonished at the wonderful detail or at its massed effect. The walls have a marvellous gallery of sculpture, with hundreds of gargoyles and figures and shields. Parts of the battlemented parapet are impressive with them, and the traveller will stand long by the peace memorial on the green, looking at the tremendous east window with Mary Magdalene in the niche above it, the quaint figures ending the window arches, and a host of curious faces centred in the parapet's panelled tracery.

All the buttresses have gargoyles, all the pinnacles are charming, and the sculpture is remarkably varied. On one east-end buttress are two men in a boat with another man pushing them off; another has two men quarrelling, one pulling the other by the hair. There is another man evidently in distress. Two odd figures at the east window have their hands on their knees. All round the walls are these faces, many worn with time but their expressions still left; it is queer to see the stones still laughing though the face has disappeared. There is a fine corbel table round the walls. The tower has a parapet walk round the spire, statues of the Apostles in niches, and a lovely west doorway with carving in its mouldings and in the niche at each side. Indoors we find similar ornament adorning the massive 13th century arch of the tower, which has smaller arches opening to the aisles. Angels adorn the nave arcades, the arches resting on lofty clustered pillars with capitals carved with foliage and faces and symbols of the Four Evangelists. The splendid clerestory runs above the arcades in the chancel.

The west window of the tower has ten stately figures of familiar saints, the north aisle has a dozen figures from the Old Testament and little scenes from their lives, and in two Kempe windows of the south aisle are the Four Evangelists and Old Testament characters.

The most precious window here is the east of the south chancel aisle, filled with a medley of old glass in red, blue, and silver; in the thousands of small fragments about 200 faces can be recognised, one piece showing two people whispering.

One thing stands out grandly in this place, the lovely screen carved in oak as the 15th century was closing. It crosses the face of the chancel and turns east to enclose the 26 stalls; black with age, it is enriched with tracery under a vaulted canopy with a cornice of vines. The stalls are fit to keep it company. They have arm-rests neatly carved with heads, quaint animals, and grotesques, and misereres among the best of their day, showing the humour and philosophy of the 15th century craftsmen. One has an owl carrying off a rat, dragons on another have crowns round their necks, a man on a monster is fighting a cockatrice, there are two lizards, and two birds are pecking grapes. In the fine poppyheads we see heads and grotesques, a bird in an oak tree, and lions and a dragon which seem to be fighting. At the end of the stalls on each side is a 19th century oak and brass screen, and there are old benches with carved ends in the chancel aisles.

Behind the high altar is a row of 13 stone seats in the lady chapel, their canopies enriched with tiny heads of animals and people. Running along the top are queer creatures, and above is a modern mosaic with 16 angels; it is a copy of Van Eyck's triptych of the Adoration of the Lamb at Ghent.

Enclosed by good modern screenwork at the east end of the north chancel aisle is the memorial chapel for those who never came back, with a tin hat worn in France, and a book of names on a bracket carved with a crouching hooded man.

The font was broken up in the Civil War, and repaired with a new bowl in 1660. The lower part of the stem is 15th century, and it is curious that each of the 16 figures round it is partly medieval and partly of the later time. Its fine lofty cover is 19th century. The pulpit was made to match the screen. The big painting of the Raising of Lazarus was once the altarpiece. There is an old pillar almsbox, and in the upper room of the south porch is part of a library left by a 17th century vicar. Modern stone figures of Mary and Gabriel are in niches by the east window of the lady chapel.

Two painted wall monuments have figures of 17th century men: Robert Ramsey, a servant of Charles Stuart in his early days (with a moustache and pointed beard) and Thomas Atkinson, who lived to see the second Charles enthroned; very miserable he looks, with a cherub and a skull to keep him company. At the back of the screen in the north aisle is tucked away the painted bust of a man like Shakespeare, a mayor of Newark in Cromwell's day. Robert Browne's tomb in the lady chapel has shields of arms; he was a 16th century benefactor of Newark, and the glass in the clerestory windows of the church was paid for out of the rents of his charity for ten years of last century. A wall memorial in the south chancel aisle is to Hercules Clay, who gave money for an annual sermon and a dole of bread. A 16th century brass of an unknown civilian is in the north transept, and at the west end is the brass portrait of William Phyllypot, who died in the same century. Let in the wall at this end of the church are two very queer faces, one with three mouths, two noses, and three eyes, the quaintfancy of a medieval mason.

An extraordinary work of art that has survived the centuries is a colossal brass, one of the four biggest Flemish brasses left in England. It is much worn, but a tracing below enables us to see Alan Fleming, who founded a chantry here in 1349 for a priest to pray daily for his household. He stands with his hands at prayer, curls on his head, his cloak richly embroidered, and all about him traceried canopies and 50 small figures.

The new reredos in the chancel, blazing with gold and reflecting the sunlight, is the work of J. N. Comper. In the centre is Our Risen Lord, and below and at each side are painted scenes and figures. We see the angels at the empty tomb, Mary Magdalene kneeling, the Raising of Lazarus, the anointing of Christ's feet at Bethany, the Entombment, Mary Magdalene announcing the Resurrection to the Apostles, and Gabriel and Mary with 14 other saints. It is the newest addition to this famous old church, a shrine to which the pilgrim in search of beauty must always find his way in Notts.

A Marvellous Man Forgotten for Centuries

WHO knows John Arderne of Newark? Yet five centuries ago he burst upon the darkened sky of England like a comet of learning and healing, then sank and left medicine and surgery to quacks and wizards. He was our first real doctor.

Where and when he was born is beyond discovery, but this fact we have in his own writings: "From the first pestilence which was in the year our Lord 1349 till the year 1370, I lived at Newark in the county of Nottingham."

Arderne was a genius of the first magnitude two centuries before Harvey. He came to London from Newark in the plentitude of his powers, and seems to have taken all our princes and potentates under his care. His patients included the Black Prince, whom he appears to have accompanied at the Battle of Crecy; Henry of Lancaster and other, warriors whose names blaze in the warlike annals of the age; and preachers, merchants, and others who formed the background of that warring era. All these he cites among the cases he had treated. He wrote books in Latin, but was not of the order of twaddling schoolmen. He seems to have known Hippocrates and Galen but nothing of his French and Italian contemporaries. How he got his skill and knowledge is a perfect mystery, but in an age which knew almost nothing of science, and appealed to magic and the moon for cures, he towers ahead of the rest of the world.

He was a brilliant operating surgeon, with a knowledge of anatomy astonishing for the period, and he taught by his books as gladly as he cured. He withheld nothing that study and practice had enabled him to perform.

There were no anaesthetics in Arderne's day, yet he insisted that the patient should be rendered unconscious before an operation, and then, "If you must cut, do so boldly; loss of blood is less, and shock minimised." Five hundred years before Pasteur and Lister he proclaimed the necessity of aseptic surgery. "Keep wounds clean (he said); they should heal without suppuration; but where this does occur assist the process by washing, that the wound may heal from the bottom upwards; otherwise do not dress too frequently."

Yet the teachings of this old seer, a miraculous man of his age with his miracles based on reason, were forgotten and lost for ages, and his work gave place to methods of gross superstition. It has remained for our own day to realise what a genius came out of Newark to offer health and healing to a disease-ridden realm.