< Previous | Contents | Next >

Amazing Timothy Hall

SUTTON-IN-ASHFIELD. This home of 20,000 people busy in factories and mines carries in its name the memory of days when it was a small village abounding in ash trees on the border of Sherwood Forest, and of the great family to whom it belonged.

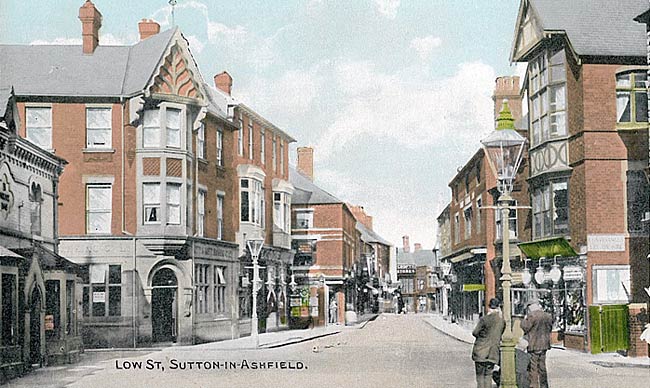

Low Street, Sutton-in-Ashfield, c.1910.

It was Edward the Confessor's village before the Conquest, and Saxon names survive in its roads; but its story is far older than Saxon, for a silver coin of Caius Claudius Pulcher 93 BC has been found in a garden in the town, and in the library is the skull of a chieftain whose skeleton was found in St Michael Street in 1892. He lay in the middle of seven men whose feet were all turned towards him, a form of burial in the later Stone Age.

Four centuries ago this village saw a tragic figure pass through its streets a few days before he was to die. He was the fallen Wolsey, who spent the night at Kirkby Hardwick a mile from here when journeying slowly to Leicester. He may have seen the manor house not far from the church, for its oldest part comes from the early 16th century.

Here came George Whitefield to preach, and here was born, in 1812, that amazing Spencer Timothy Hall, who could plough and reap, stack and thresh and winnow, make a stocking and a shoe, write a book and print and bind it, and cure all sorts of ills. Perhaps the most astonishing Jack of all Trades of his day, he sleeps at Blackpool, but he is still known as the Sherwood Forester, and will long be remembered here.

The church of St Mary Magdalene, Sutton-in-Ashfield, in 2003.

A long avenue of limes leads us from the road to the churchyard, which has an ancient yew said to be 700 years old, with a trunk slender for its years and shorn of half its spreading branches. In its shade are 18th century stones of the Brandreth family, relatives of the Jeremiah Brandreth who was executed as leader of the pitiful Pentrich Rebellion (in which Shelley interested himself) during the general unrest after Waterloo. A stone by the path leading to the porch is in memory of Ann Burton, who, if she did nothing worth recording in her life, achieved something remarkable at the end by dying on the 30th of February in 1836. It is one of several records we have found of days that never were.

The church is of light-coloured local stone, and has some interesting old remains in spite of severe restoration. Built by the Suttons in the 12th century, it was given by them to Thurgarton Priory, and John de Sutton in the 14th century left money to build the tower and spire. An ancient floorstone in the chancel, engraved with a great bow and arrow, is said to have had an inscription to one of the Suttons. Another interesting relic of the family was found when the sexton was digging a grave in 1870. It was a tiny 14th century metal seal with a ring for hanging it round the neck, carved on one side with a fleur-de-lys and on the other with a monk and an acolyte sitting with open books. Above the monk was a squirrel cracking nuts.

The nave arcades come from the close of Norman days, and the chancel arch is half a century later. A lovely 13th century fragment is at the east of the north arcade, its three shafts crowned by a capital with three heads. The round bowl of a Norman font has been rescued from the vicarage garden. The top of a small shaft piscina, with scroll ornament, is a century older than Magna Carta.

Names of over 200 men "who gave their lives for their country and their souls to God" are remembered here. One has a memorial window, and an inscription tells of another who perished while attending the wounded near Armentieres.

Just outside the town on the road to Mansfield is a fine reservoir made by the Duke of Portland in 1836 for irrigation of his meadows. It helps to grind flour in the stone mill close by, made new but still known as King's Mill, its name perhaps recalling days when kings came to their royal manor of Mansfield to hunt in the Forest.

The Rare Old Screen

SUTTON-ON-TRENT. It touches the Great North Road, and goes down in an unbroken sweep of meadows to the Trent. At one end of the village a lovely old church adds beauty to the road; at the other stands an old windmill with derelict sails. A turn of the road near the church leads by a wayside stream to pretty gardens, one delightful with a rockery, old-world pump, and well.

Sutton-on-Trent church in 2001.

The church came into Domesday Book, and its 13th century tower with a 15th century top still stands on its Saxon foundations, though it lost a spire a century ago. Deep battlements, with gargoyles below them, enhance the beauty of a remarkably fine 15th century clerestory, and faces adorn the windows all round the church.

A handsome addition is the early 16th century Mering Chapel, which may have been brought here from Mering across the river. Pinnacles enrich its buttresses and rise from its parapet, which is carved with flowers, shields, faces, and gargoyles; one gargoyle shows two lizard-like creatures coiling round a head. A beautiful roof looks down on the rich work inside, where great windows with fragments of rich old glass fill it with light. The walls are enriched with arcading, shields, and brackets, and the lovely piscina is one of three in the church. Two arches between the chapel and the chancel rest on a beautifully carved pillar, and under one of them is a great tomb, perhaps of Sir William Mering. Dividing the chapel from the aisle is a rare oak screen of about 1510, with delicate carving of tracery, bands of quatrefoils, and trailing flowers. Its loft,, seven feet wide and almost like a gallery, overhangs both sides. It is a pity so fine a screen has been spoiled for the sake of the organ.

The sides of the chancel arch are late 12th century, but the arch and the nave arcades are a hundred years later. The bowl of the font may be 17th century on a medieval stem: its pyramid cover and the altar are Jacobean. Among the poppyheads of 15 old stall-ends are birds, bearded faces, a grinning face, and two women smiling at each other.

Lovely for its 14th century stonework and for its modern glass is the east window of the north aisle, shining with figures of St George, St Gabriel, the Madonna, and St Ursula. Except for some old fragments, it is the only coloured glass in the church.