IV.—THE CIVIL WAR.

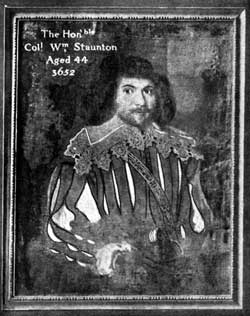

Some years ago Mrs. Lucy Ada Staunton wrote and published an interesting pamphlet upon the life of William Staunton, and from this source many of the following facts are taken. The Staunton papers tell us little more about him than is recorded above until after August 22nd, 1642, the eventful day on which the King set up his Standard at Nottingham as a sign of war. Here came William Staunton to his Sovereign's aid, accompanied by a gentleman, his male servants, and his tenant's sons, duly armed and equipped. He followed Charles I. to Shrewsbury, and fought for him at Edgehill and Brentford. After Edgehill the King gave him a Colonel's commission, and recognising his enthusiasm for the Royal cause, and his influence in his native county, authorised him to visit Nottinghamshire to raise troops.

Colonel Staunton therefore returned for a while to his home, but not to rest. In a short space of time he enlisted, armed, and equipped a regiment of 1,200 foot and a troop of horse at his own cost. The horse were under the command of the gallant Sir Gervase Eyre, who during the siege of Newark so greatly distinguished himself in the many conflicts which took place round that ancient town. There are several Commissions relating to various posts in Colonel Staunton's command, and under date 16th August, 1645, an order from Charles I. requiring him to draw his regiment from the Garrison of Newark and with them march to Tuxford and so forward under the orders of Lieutenant-General Villiers.

A list of these documents may be of interest:

- Authority to raise troops.

- Colonel's Commission to one regiment of Foot signed by William Earl of Newcastle.

- Appointment of Gervase Huett Lieutenant of one Troop of Harquebusiers (same signature).

- Blank Commission of Captain of one Troop of Harquebusiers (same signature).

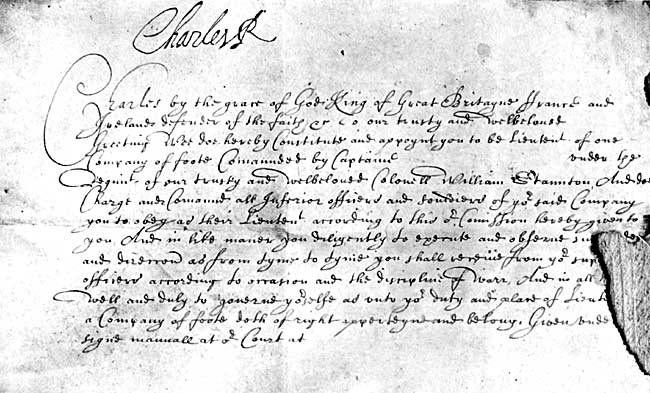

- Blank Commission of Lieutenant of one company of Foot, signed by King Charles.

- Similar Blank Commission signed by the King.

- Orders to withdraw regiment from Newark, signed by the King.

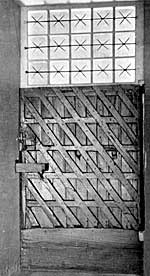

Front door, Staunton Hall.

In the beginning of 1645, Staunton Hall, which was held by Mrs. Staunton and a feeble garrison of retainers unfit to follow their master in the field, was attacked by the Parliamentarians. The house, unable to withstand a siege, was speedily taken by the enemy, the marks of whose assault are visible in the old oak front door, where the holes made by their artillery still remain. Mrs. Staunton fled by way of the Great North Road and finally took refuge in London, while the enemy despoiled the house. All the furniture and valuables which could be discovered were confiscated, and the following receipt shows what occurred in some cases:—

"16 Jan., 1645. Rec(eived) then of Mr. Robert Hill, minister of Killvington, the some of twenty-nine shillings for goods formerly belonging unto Coll Staunton and now sequestred, apprised and solde to him for the use and service of the State; the particulars of the goods being four cheyres w(ith) Turkyworke seats, 2 cheyre frames aud one brass panne. I say rec(eived) p Will Farburne, agent for Sequestracons p Com. Nott."

The finding of this receipt at Staunton indicates pretty clearly that the Rector of Kilvington, in the interests of his patron and friend, purchased some of the loot from the Puritan soldiers. Doubtless the chairs with the Turkeywork seats, the damaged chair frames, and the brass pan found their way back to Staunton Hall when its owner made his peace with the conquerors: the receipt for 29s. being produced by Mr. Hill in evidence of the amount paid for them.

In the memoirs of Col. Hutchinson (Ed: Firth, 139) occurs the following passage: "About this time a woman was taken, whereof the Committee had before been informed that she carried intelligence between Col. Pierrepoint and his mother the Countess of Kingston. The woman was now going through Nottingham with letters from the old countess to her daughter-in-law, the Colonel's wife, who was then at Clifton, Sir Gervase Clifton's house. In this pacquet there was a letter drawn which the countess advised her daughter to sign to be sent to Colonel Stanton (Staunton), one of the King's Colonels, to entreat back from him some goods of her husband's which he had plundered; wherein there were these expressions:— That although her husband was unfortunately engaged in the unhappy rebellion, she hoped ere long he would approve himself a loyal subject to his Majesty." The following letter, doubtless written purposely in the vague and guarded manner rendered necessary by the frequent interception of correspondence in those times, bears upon this incident:—

"Ladie

I am taxed for p(ro)curing some order of ye Com(m)ittee to yr disservice, and therefore desired to endeavor ye revoking it. This I should be unwilling to denye, if I were ye cause of yr suffering; But if ye Com(m)ittee take notice that Colonell Stanton hath not donne my Master that right he p(ro)mised him, and thereupon denye you that favor they intended you, I suppose till Mr. Stanton hath p(er)formed that, they will not grant this though I request it, since they value more Mr. Pierreponts interest then (than) any words of mine. It rests therefore more in yr own power than mine to p(ro)cure what is kept from you, wch I believe by this time you may be able to doe, and thereby you may right yrself and oblige my Master, whoe (I am confident) will soe farre exceed in his Civility to you, that you will soone finde ye advantage you gaine in his friendship. I have lately written to him about this business, and soe soon as I receive his answer shall doe his commands, wch I wish may tend to yr service, wch I shall studdie to advance for I am

Ladie

Your most humble servt

Tim Keatlewell." 11 Junii 1646.

Two days later Mrs. Staunton obtained the following order: "This is to require all Officers and Souldiers belonging to this garrison and to desire all Officers and Souldiers raised by authority of Parliament, to p'mitt Mrs. Anne Staunton or whom she shall appoint to looke into and oversee the repaires of the Mannor house of Staunton in the County of Nottingham (late belonging to Col. W. Staunton, a Delinquent to the Parliament service) and there to remain dureing such time as the said house shall be in repairing (as alsoe for securing the house for the end noe waste or spoil may be made there) without any yor let or molestation. Given under or hands the 13th day of June 1646, Jos. Widmerpole, Nico. Charlton. John James, Th. Salusbury.

On 11th May, 1647, Colonel Staunton had an assessment of £800 imposed upon his estate by the Parliament. At the time he took no notice of this, but on the 17th January, 1651, after he had made his peace with the Government, an order was made that, on deduction of his debts and payments made in the County, this assessment should be discharged on payment of £130. This sum was paid on 14th March, and an order made for full discharge, but seven days later Colonel Staunton petitioned that "he was assessed at £800, but on being ordered to pay £130, besides £100 which he paid in the county, and this he has done, yet the county commissioners demand 6d. in the pound on the £800, and have driven away his cattle and sold them for the fees which cannot justly be required. Begs that the cattle may be restored, and he no further molested." An order therefore was made on the same day that the County Commissioners claim only 6d. in the pound on the money paid in.

Lieutentant's commission in Colonel Staunton's regiment.

It is not proposed to describe the life of Colonel Staunton while serving in the garrison at Newark, as it is mainly the history of that town, its sieges, and afflictions. In October, 1646, King Charles departed from Newark with Lord Digby, on his way to join the gallant Montrose in Scotland, and Colonel Staunton accompanied him with his regiment. At Rotherham, however, news was brought that Montrose, instead of being at the head of a victorious army, as was supposed by the King to be the case, was in reality a fugitive. Nevertheless, Lord Digby, whose vanity exceeded his ability, obtained permission from Charles to take 1,500 troopers with which to go to Montrose's aid. Accompanied by Sir Marmaduke Langdale he set off, but in a few days his force was defeated, and he himself sought refuge in the Isle of Man, which he reached in a fishing smack.

Charles returned to Newark and Colonel Staunton with him. Soon after their arrival, Prince Rupert, who was in disgrace over the loss of Bristol, came from Belvoir Castle to explain his actions to the King. All the principal Cavaliers in Newark, with the Governor at their head, went out to meet the gallant Prince, who at an interview with the King, successfully cleared himself of the charge that he had yielded Bristol without sufficient defence. Next morning, however, Rupert took offence at the removal of his friend, Sir Richard Willis, from the Governorship of the town, and withdrew with his friends, some four hundred in number, to Wiverton, and afterwards to Belvoir; "the King looking out of a window and weeping to see them as they went." Colonel Staunton, however, remained at Newark until its surrender in May, 1646, when he laid down his arms.

On the 6th July following he compounded with the Parliament for having borne arms for the King, and on the 12th of next month his fine was fixed at £1,520. With great difficulty he raised half this sum, but on the 12th May, 1649, he was obliged to petition that some consideration should be shown him, his property having been wasted and his woods cut down. His petition was favourably considered, and the fine was reduced to £828 3s. 6d.

PETITION OF WILLIAM STAUNTON.

"To the Right Honble. the Comission for Composition with Delinquents sittinge at Goldsmiths' Hall.

The humble petition of William Staunton, of Staunton in the County of Nottingham, Esqr.Sheweth,

That your petitioner submittinge to the fine imposed on him for his delinquency did accordinge to order pay one moyty unto the treasurie of this Comittee and although he hath used his utmost endeavours by all means possible for paiment of the remainder either by mortgage sale or otherwise, yet by reason of his greate sufferinge in his goods, fellinge of his woods at the seidge of Newarke for the use of the state, with which he should have raised money, the many judgments and extents upon his estate not allowed him, and being through mistake much overfined, hee comeing in upon the articles of Newarke, but not allowed him as to others comprised within the said Articles by reason of all which your petition is utterly disabled to raise money for his second paiment unlesse you shall afford him the like mercy as others have received in his condition.

May it therefore please your honors in kinde consideration of the premises and out of your accustomed clemency to recommit the cause of your petitioner to the sub comitee that be they may make report thereof to your honors as they shall finde the case to appeare.

For which he shall ever pray, &c.

[Endorsed] Recd 4 May 1649

and admitted and referred

to the examination and

report of the sub comittee.Jo: Leech."

Particulars of the damage caused by the Parliament soldiers in Staunton to Colonel Staunton's property, estimated by him as follows :—

Loss of household goods.................................... |

£300 |

|

Woods cut down ................................................ |

300 |

|

Spoils and waste committed on his houses........ |

2000 |

|

|

——— |

£2600 |

It might have been supposed that Colonel Staunton had suffered enough for his devotion to the Royal cause, but next year further trouble fell upon him, and from an entirely unexpected quarter. When Newark was set in a state of defence for the King, large sums of money, amounting, according to Mrs. Hutchinson, in her Memoirs, to between eight and ten thousand pounds, was advanced by certain merchants of this town to the Commissioners of Array to defray the cost of the necessary works. Mrs. Hutchinson, as will appear, had the best of reasons for knowing all about this affair, but the Record Office gives particulars only of the following amounts:—

From William Baker of Newark ............................ |

£150 |

|

William Barrett of Newark ............................... |

530 |

|

John Chambers of Hull .................................... |

1500 |

|

Hercules Clay of Newark...................... ........... |

600 |

|

Mr. Ware and Mr. Fisher .................................. |

160 |

|

|

|

£2940 |

The largest of these sums, that of £1,500 in the name of John Chambers, was in reality a loan from a man named Atkinson of Newark, who employed this means to conceal the transaction. The King's Commissioners, though the money was used in the Royal Cause, gave their personal bonds as security for repayment.

Colonel Staunton.

On the surrender of Newark, the above-named merchants had to compound for their delinquency, and in disclosing their possessions to the Parliaments Committee for Compounding should have set forth these bonds. Relying, however, upon the silence of the gentlemen by whom the bonds were signed, they said nothing about them, and were admitted to composition on terms more favourable than would otherwise have been the case. Shortly afterwards Atkinson approached Lord Lexington and Sir Thomas Williamson, as being the wealthiest of the signatories, and demanded repayment. To this they consented, but were unwilling to pay interest upon the loan. Atkinson, however, would not accept these terms, and actually caused Sir Thomas Wilkinson to be openly arrested for the debt in Westminster Hall. This unwise action brought the whole matter to light, as Lord Lexington and Sir Thomas Williamson filed a Bill in Chancery against the merchants, praying that they might set forth to what ends and uses the money was lent.

Parliament had passed a law that all estates of delinquents concealed or uncompounded for should be forfeited, one-half to the State and one-half to the discoverer if he had any arrears due to him from Parliament. It therefore became a practice among certain solicitors and clerks at this time to ferret out such cases, and reveal them, for a consideration, to persons having arrears due to them. Colonel Hutchinson, who so far had received no payment for his services, was informed that two officers were on the track of these bonds, but according to his wife he made no move in the matter. Later on, however, he was led to believe that Lord Lexington and the others preferred—as the business was bound to be made public— that he should make the discovery, the Nottinghamshire gentlemen concerned preferring to fall into the hands of a neighbour rather than strangers should have the collecting of this debt. Mrs. Hutchinson states that Lord Lexington was made a peer because at the time this money was borrowed he represented to the King that he had personally raised it for the Royal cause. He now arranged with Colonel Hutchinson that his estate and those of the other Royalist's should be sequestrated until the money was paid, but that their own bailiff should be placed in charge, so that it should cause them as little inconvenience as possible. The following letter to Colonel Staunton suggests that Mrs. Hutchinson's account of this transaction is unduly favourable to her husband.

"To my noble kinsman, Mr. Staunton, Esquier, this present

at Staunton.

Sir. There came a letter to my hands yesterday by the post dyrected to yourself and myself and sum others. I opened it and found it from Mr. Hutchinson the busynes concerninge the three bonds of Mr. Chambers, Mr. Barret and Clay in wch it seems we have your Company. As it is your fortune to be in the Bondes so I desyer the favor you will be here of Thursday next, nyne in the morninge to consyder with the rest, who I suppose will not fayle to meet you here, what to propose to Mr. Hutchinson. I sent the letter to Sir Th Williamson because most of the Gentlemen are of that syde that were to have notice, and undertook to give Sir Roger Cooper and yr self notice. Sir Eoger will be here and hath sent one of purpose to Sir John Digby. The contents of the letter pretends cyvylyty (civility) and that he is unwillinge to take any vygorous cours yf wee be not wanting to ourselves and therefore desyres wee will meet but you will see the letter and till then I will not increase your trouble. I adventured to appoynt this place but with this that yf they lyked to appoynt any other I shold by Gods leave not fayle. I proposed that advantage to myself to see so many of my good friends under my poore roof wch is all I can expect in this business. My Wyfe and self presents our Services to my sweet cozen and yourself. I wish eyther power or opportunity or any measur to serve you in wch I should appeare Sir

Your faythfull kinsman

and humble servant

Ro. Lexington.

Kellam

July Tuesday.

In the end, those gentlemen who, as the King's Commissioners, had borrowed this money for his service, had to repay it out of their own estates, already diminished by their sacrifices in the Royal cause, and by the fines inflicted on them, which in some cases amounted to one-third of the total value of their possessions. But the merchants who advanced the loans derived no benefit from their neighbours' misfortunes, as the whole sum was confiscated by Parliament, £2,800 being bestowed on Colonel Hutchinson. On the restoration of Charles II. Lord Lexington caused an Act to be passed through the House of Lords providing that this money should be repaid out of Colonel Hutchinson's estate, but it failed to pass the House of Commons.