< Previous | Contents | Next >

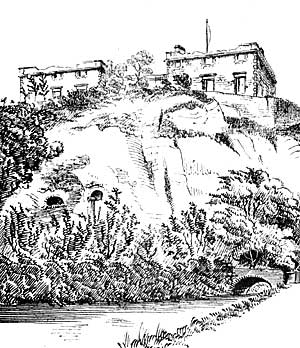

The 17th century Ducal Palace (after the fire). The "inaccessible rock" — 130 feet high.

One of the most successful generals in the Royalist army during the wars was William Cavendish, son of Sir Charles Cavendish of Welbeck Abbey, victor in 15 battles and sieges, and affectionately termed “the loyall Duke.” Not only did he contribute vast sums of money to the cause, but he personally raised troops in the service of the King. He was appointed to the command of the forces north of the Trent, and manned and fortified the town of Newcastle-on-Tyne For his allegiance and service Charles I. raised him to the Peerage by the title of Lord Ogle and Viscount Mansfield, and afterwards created him Earl of New-castle-upon-Tyne. During the Commonwealth period he went to reside on the Continent, enduring much hardship, but at the Restoration he returned to this country and Charles II. raised him to the dignity of Duke of Newcastle. He purchased the ruined and dismantled Castle and estate from the Duke of Rutland, cleared the site of almost every vestige of the mediaeval work, and in 1674, although in the 83rd year of his age, commenced to build a palatial residence on the highest part of the rock, on the site of the original Norman fortress. The building was designed in accordance with the prevailing style of architecture, probably by the Duke himself, for in his will he states “I have begun to carry up a considerable building at Nottingham Castle, which I earnestly desire may be finished according to the form and model by me laid and designed.”

His son Henry Cavendish, the 2nd Duke, assisted by an architect, or clerk of the works, named Marsh, carried the work to completion in 1679.

The style of architecture adopted, known as Free Classic or “Renaissance"—(i.e., when applied to architecture, the revival of classical or Italian forms) —is altogether unsuitable for such a site, the multiplicity of horizontal lines produced by the “rusticated” jointing of the masonry, and the long straight cornice and ballustrade, being out of harmony with the precipitous lines of the escarpment of the rock on which it is built. The long unbroken facade on the eastern side, adorned with Corinthian columns of somewhat clumsy proportions, and the upper tier of small square windows with a peculiar arrangement of scroll work around the architrave, all tend to emphasize the squatness of effect.

The entrance was in the centre of the eastern front, approached by a fine flight of geometrical stone steps, and above the doorway the remains may still be seen of what was once a fine equestrian statue of the 1st Duke, surmounted by his armorial bearings and crest. The figures were said to be carved out of a single block of stone brought from Castle Donnington, by a sculptor named Wilson, but at the time of the riots it was discovered that one of the legs of the horse was made of wood. The 1st Duke was an accomplished horseman, the author of a celebrated treatise on horsemanship—the manuscript is still preserved at Welbeck.—He built the first riding-house for private amusement in this country at Bolsover, and afterwards the more famous one at Welbeck.

From the time of its completion the Castle became the occasional residence of the Dukes of Newcastle and other persons of rank and title. During the troubled years previous to the flight of King James II his daughter, the Princess Anne, took up her residence here; and judging by the survival of such names as “Queen Anne’s Garden” and “Queen Anne’s Chamber,” there is reason to believe that after her accession in 1702 the Castle became at times the residence of the last of our Stuart Sovereigns.

About the year 1795 the rooms were divided and let off to separate tenants, one portion being used for a time as a boarding school.