< Previous | Contents | Next >

It was chiefly owing to the exertions of the Corporation that the Church had been rebuilt after the fall of the tower, and till quite modern times they continued to subscribe liberally to what was known as the Corporation Church. They had appropriated to themselves much property which had been left to them in trust for charitable and religious purposes, which property they used for their own private advantage, feasting and drinking at the public expense, and the amount they gave away bore but a small proportion to the amount they kept. Among their subscriptions to the Church was £31 10s. 0d. towards a new vicarage in 1773; five guineas to buy three chandeliers in 1787; five guineas towards a new organ in 1788, when they also provided music for the choir. Three years later they voted ten guineas annually for the organist's salary. In 1817 they gave six guineas for a new stove, and in 1835 they provided a new peal of eight bells at a cost of £490.

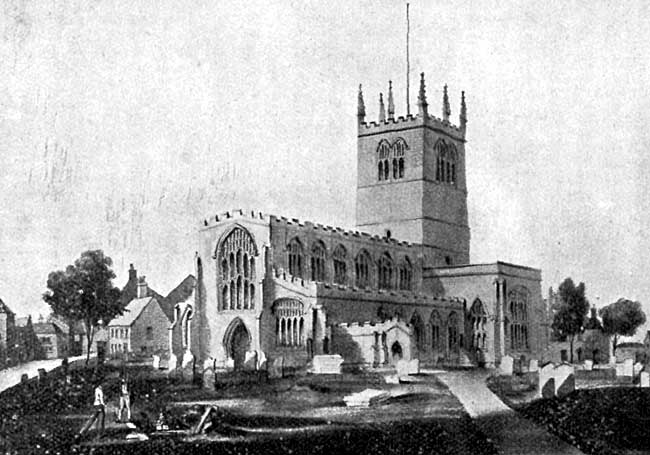

But in spite of what was done the general state of the Church during the first half of the 19th century grew steadily worse and worse. Piercy writing in 1828 says it was in "excellent condition on the outside, but only in moderate repair in the interior," and this was at a time when men's ideal of what a church should be, was at its very lowest. But a change was soon coming.

In 1833 Keble preached his Assize Sermon and the Oxford movement began, a movement pregnant with change not only for the services, but also for the fabrics of our churches. An era of restoration set in. Too often it was directed by those who had little knowledge or love of what was ancient, and much wheat was destroyed amidst the tares which were plucked up. Yet though we have lost much, we have certainly gained more. The change, however, was slow in spreading over England, and in the middle of the 19th century East Retford Church was at its worst.

In a paper read before the Lincoln Architectural Society in 1854, Mr. Hawksley Hall, who was secretary for the restoration fund, has left us a vivid account of what the Church was then like. All the external masonry was in bad condition, the holes in the walls being blocked up with tiles which were covered with mortar mixed with coal dust, and even this had fallen away in parts. The pinnacles were all in ruins with the exception of one at the south west angle of the south aisle.

East Retford church about the year 1850.

The interior was filled with big irregular box-like pews, in which their owners could comfortably slumber unseen. They were considered as private property, and their sale and letting was a common transaction, the purchase money going into the hands of the private owners. The scandal was so notorious that in 1852 Archdeacon Wilkins wrote to the Churchwardens to protest against the practice.

The Church was almost surrounded by galleries, and in the nave stood a huge three-decker, at the bottom of which sat the clerk, at that time, J. S. Piercy, the author of "A History of Retford."

The floor of the Church was damp and rotten, the roof of the nave flat and ugly, and the other details of the building were of a like character. It is even said that grass was growing in the north aisle, which was at one time the keeping place of the parish fire engine. Everything spoke of a religion without beauty and without enthusiasm. Yet at first all suggestion of change was bitterly resented, and it was only at last carried out by the continual pressure of a few enthusiasts, among whom Mr. Hawksley Hall occupied a leading position. Most people love with an unreasoning prejudice the things and ways to which they have been accustomed, and the objection to change was no peculiarity of the people of that time.

A beginning, however, was made with the south porch in 1852, and in 1854 a thorough restoration was undertaken under the advice of the architect G. G. Place, of Nottingham.

The whole of the exterior masonry was repaired. The buttresses were rebuilt on the old foundations, and new pinnacles were erected. The south transept, which previously had a square parapet, was now gabled and battlemented, and the north aisle was entirely rebuilt and widened. The galleries and the irregular pews were swept away, and the Church was refitted with the present pitch pine seats. It is to be hoped that the time is near when these may be replaced by oaken benches with carved ends, such as used to be the glory of the ancient churches.

At the same time the present roof of red deal was given to the nave, and a new roof was also added to the south aisle. The walls were cleaned, and unfortunately most of the stone was retooled.

The chancel was enlarged so as to be the same size as it was before the tower fell, the old foundations having been discovered. A new organ chamber was built on the south side of the chancel, and the organ was removed there from the west gallery, a change which was by no means an entire advantage for congregational singing. The total cost was about £5,000, of which nearly £1,000 was raised by a bazaar held in September, 1854.

The opening services took place on the 11th and 13th of September, 1855, when ten choristers of Norwich Cathedral assisted the local choir. The sermons on the first day were preached by Dr. Jackson, Bishop of Lincoln, and by Archdeacon Wilkins, of Nottingham; and on the second by Dean Hook, then Vicar of Leeds, and by Dr. Hessey, of St. Barnabas, Kensington.

At the same period the railings and gates to the churchyard were erected at the cost of the Corporation, and the two chestnut trees at the main entrance were planted by Dr. S. Marshall and Mr. E. Plant. This was the last occasion on which the Town Council gave anything to the Parish in their corporate capacity, but as individuals, they have never ceased to take a practical interest in the ancient Corporation Church.

The last important addition the Church received was in 1873, when the present chantry was built from the design of Mr. G. F. Bodley, so as to serve both as a side chapel and as a vestry. It is on the same site as one or more of the original chantries, and extends fourteen feet eastward from the north transept. When it was being built the old foundations were discovered, from which we may infer that the earlier building was much deeper than the present one, extending twenty eight feet further eastward. The cost of the chantry was nearly £700, and it was opened on the 6th of October, 1873, by Dr. Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln.

In this year, 1905, the jubilee of the restoration, the Church has once more been put in thorough repair. Most of the stone used for the outside of the church seems to have been brought from the quarries of Roche and of Steetly, but for the restoration in 1855 Ancaster stone was used. This had weathered very badly, and wherever it was decayed, it has been replaced by stone brought from the Ketton quarries.

Carved oak doors have been given for the west entrance by Mr. G. Lister Hopkinson. The floor of the aisles have been laid with Minton tiles, and the wall of the north transept has been pannelled with oak, the last being done at the expense of Miss Anne Roberts, in memory of her mother. The lobby leading into the chantry has also been widened.

Altogether a sum of upwards of £1,000 has been spent.

The beauty of the Church has steadily increased during the last fifty years, each generation having borne its share of the work. Much remains that might yet be done, but if the parishioners and the congregation continue to feel a pride in this ancient House of God, it may yet attain the magnificence which the English churches possessed before the Great Pillage of the reign of King Edward the Sixth.