CHAPTER VII

THE ECCENTRIC DUKE AND HIS UNDERGROUND TUNNELS

Bust of the 5th Duke of Portland, by Sir E. Boehm (1880).

The story of the transformation of Welbeck enters upon a new stage with the succession, in 1854, of the Marquis of Titchfield (William John Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck) as fifth Duke, born in 1800. He it was who designed and had constructed the mysterious underground apartments and tunnels for which the Abbey and its environs are famous. There were miles of weird passages beneath the surface of the earth, one tunnel alone being nearly a mile and a half in length, stretching towards Worksop, while others ran in various directions.

Welbeck is nearly 4 miles from Worksop, and a stranger on approaching the Abbey is likely to receive a mean impression of its vast extent. The architecture is a mixture of the Italian and classical styles, and its having been built at different periods, with so many of its adjuncts underground, makes it wanting in imposing features. In various parts of the estate about 50 lodges were erected for the occupancy of gardeners and keepers. They were of Steetley stone, all similarly planned and pleasing to the eye, what there was of them above ground; but the Duke had subterranean kitchens made at the side and lighted them with bulls-eyes at the top.

He spent about 100,000l. a year in the development of his plans, and employed as many as 1,500 workpeople in helping him to gratify his hobby. When it is remembered that his reign as Duke lasted a quarter of a century, from 1854 to 1879, it will be seen that artisans of all descriptions found Welbeck a veritable gold-mine. Even so late as November, 1878, a Nottingham newspaper correspondent, on visiting Welbeck, was impressed with its appearance as that of the premises of “some great contractor who had an order for the building of a big village.” There was the buzz of machinery, large areas were covered with bricklayers’, masons’, and joiners’ sheds, wherein any new mechanical contrivance was put to the test. For more than eighteen years the vicinity of the house resembled a builder’s yard, in the centre of which the Duke lived and moved and had his being, enjoying, in his way, the piles of bricks and mortar surrounding him. After he had decided upon the erection of a new building he had a model of it made for his inspection, and if approved of, it was proceeded with.

Any tramp or wayfarer who applied for work at Welbeck was put on the staff, and the market value of his labour paid. The Duke seemed to find grim pleasure in the society of the casuals who made their way to his stone-yards.

The wing built by the Countess of Oxford in a former generation had a new storey put to it, with a magnificent suite of 14 new rooms furnished in Louis XIV. style, richly gilded, and with mantelpieces of white marble.

An underground passage was made leading to the old riding school, built by the Duke of Newcastle in 1623, but since converted to other uses, such as a library and church, after the erection of the new riding school. Beneath it are great wine cellars with subterranean communications.

The most wonderful of the underground apartments built by the Duke was the picture-gallery, or as it was intended to be, the ball-room. It is lighted from the roof by means of bulls’-eyes. An enormous sum was spent in labour, excavating the solid clay in order that this magnificent saloon might be constructed.

Some choice examples of the great masters are contained in this palace of art, which is 158 feet long, 63 feet wide, and 22 feet high. Here are examples of the works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, de Mytens, Tintoretto, Teniers, Snyders, Bassano, Wyck, de Vos, Greffier, Francks, Berghem, Zucchero, Wootton, Breughel, Dirk Maas, Netscher, Cagnacci, Gerard Honthorst, Van der Meulen, Rigaud, Vandyke, Holbein, Kneller, Lely, Dahl, M. Shee, Knapton, West, Jansen, Verelst; in fact not only in the picture-gallery, but in all parts of the Abbey are scattered treasures of art and vertu. Among the interesting curiosities are the one-pearl drop-earrings seen in the portraits of Charles I., and worn by him on the morning of his execution; also the silver-gilt chalice from which he received the consecrated wine on that fateful morning at Whitehall. The chalice bears the following inscription: “King Charles the First received the communion in this Boule on Tuseday the 30th of January, 1664, being the day in which he was murthered.” In the library are autograph letters from the Stuarts, including one from Mary Queen of Scots, signed “Your very good friend.”

There is a portrait of Adelaide Kemble, with whom the Duke is said to have been in love in early manhood. The actress is in the pose of her histrionic profession, and in another part of the gallery is a bust of the Duke by H. E. Pinker (1880).

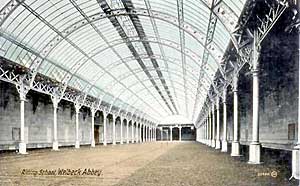

The Riding School.

The gigantic riding school is about 380 feet long, 112 feet wide, and 50 feet high, and from it is a subterranean passage leading to the tan gallop, designed for the exercise of horses. The length of this gallop is 1270 feet, and it is all under a glass roof. He had about 100 horses, and his stables extended over an area almost as large as a village.

Of all his extraordinary hobbies that of planning subterranean passages has excited the most wonder and satire. These tunnels, in which it was possible for three persons to walk abreast in some parts, were lighted with gas jets placed at intervals. One at least of the tunnels is large enough for a horse and cart to be driven through.

The drive from Worksop is a delightful one, but all at once the stranger is surprised to find himself in a cavern, leading as might be supposed to the catacombs. It was no uncommon thing for the Duke to rise up out of a tunnel and appear in the midst of a gang of workmen when they were little expecting him, and when, perhaps, they were idling their time, or making uncomplimentary remarks about him.

When the tunnels were in course of construction there might be seen a procession of men on donkeys going to and fro. It was all in a piece with his Grace's conduct that he should purchase donkeys for them to ride upon; but the animals, when let loose, would gnaw at the trees, so the services of the four-legged asses were dispensed with.

His manner of dealing with a strike was a summary one. The wages of the excavators of the tunnels were fifteen shillings a week regularly, sunshine or rain; but the men thought their rich employer could afford them an increase, so they struck.

“You can strike as long as you like,” was the message sent by the Duke, “it does not matter to me if the work is never done.”

This cool attitude had its effect, the strike was at an end, and the tunnelling proceeded.

Tunnel entrance at Welbeck Abbey.

One reason given for planning the tunnels was that when he first desired to withdraw himself from observation he tried to close the public rights of way over the estate. This brought him into collision with the powers that be, and he compromised matters to his own satisfaction by making the underground roadways. His cynicism was rich.

“Here have I had provided for you at enormous expense a clean pathway underground, lighted with gas too, and you will persist in walking above ground,” was his salute to some astounded visitors. The idea that they should prefer the sunshine, the delightful woodland scenery and sweet-smelling scents wafted over Welbeck in summer-time, to the gaseous tunnels, as if they were rabbits having natural affinities to the burrows of the earth, was one only worthy of a ducal misanthropist.

He was “The Invisible Prince,” he liked to take men unawares, he enjoyed a grim joke at their expense, though whether he ever showed signs of merriment, at least in after life, is not so much in the memories of those who knew him, as his eccentricities. He is more associated with the character of an ogre and a cynic who shunned his fellow-men, yet there are some of his employees still living who give him a good word as a kind and considerate master.

There have been various reasons put forth to account for his withdrawal from the society of his peers. It was said that he was smitten with leprosy, that he had an incurable skin disease; then that his love affairs had gone awry when he was a young man, with the result that he became a woman-hater, then a hater of mankind generally.

The Duke was moody and uncertain in his temper. Sometimes he would pass pedestrians in the park without noticing them; at other times strangers would be astonished to hear a shabby old ogre break out at them in profane language because of their intrusion upon his domains, and they would be still more astonished when making complaints about the conduct of this disreputable person, to find that it was the Duke himself.

At that time the use of a traction-engine in agriculture was somewhat of a novelty, and because it was different from the appliances generally used by farmers, was a recommendation to the Duke.

It was nine o’clock one night when he said to his haymakers: “Take the carts home and bring another load with the engine.”

“Excuse me, your Grace,” said one, “If the engine is made of steel and iron I'm not. I'm tired out.”

“Well, perhaps you are, go home then,” came the order, which is testimony to the consideration he had for his employees when he was addressed in a manly, straightforward way.

There was a grotesque procession one day at a farm on the Welbeck estate. It was a rainy summer, and the farmers were at their wits’-ends to know how they were to secure their hay in anything like good condition.

The Duke was not a man to be beaten by the weather; he defied it; he was determined to have his grass in the rickyard, wet or dry. So the order went forth that his traction-engine and waggons were to be ready for carrying it on a certain day.

There was to be no shirking, for the Duke’s intention was to be with his men to see that the work was done. So he went to the farm in his long brown cape and high silk hat and an umbrella which might have done duty for Hans William Bentinck in the swamps of Holland.

The harvesters filled the waggons in a downpour of rain and the cavalcade started for the homestead. There were three or four wagons behind the engine, and in the last, lo and behold, sat his Grace, grim, silent and self-satisfied that the elements had no terrors for him.

What a life his was to lead; he was a veritable prisoner, having himself for a warder.

The special apartment used by him in the daytime was fitted with a trap-door in the floor, by which he could descend to the regions below, and thus roam about his underground tunnels without the servants knowing whether he was in the house or had left it. By means of this trap-door, after walking to some distant part of his estate and astonishing his workmen there, he could re-appear in the Abbey as mysteriously as he had left it.

The apartment with the trap-door had another door opening into an ante-room, and here his servants received their orders.

The “Prince of Silence” rarely spoke to his attendants; he wrote down on paper what he required and placed it in the letter-box of the door opening into the ante-room. Then he rang a bell, when a servant would come and read what he had written and carry out the order accordingly.

The Duke’s bedstead was an immense square erection, constructed in an extraordinary manner.

There were large doors to it, so arranged that when folded it was impossible to know whether the bed was occupied by its owner.

He was a lonely traveller, and even when he went to Paris would have no companion with him. His arrangements were made by an avant courier, and when it became known that he had arrived in the gay city, the English aristocracy paid formal visits to him.

These attentions were too much for his habit of loneliness, and he vanished to St. Germains. A few weeks’ stay here was enough for him, and he came back to Paris, not lingering more than a couple of days, and then proceeded by stages to Calais and on to London.

One of the best authenticated stories of the fifth Duke relates to his habit of riding alone in a carriage specially constructed to secure privacy. As was natural the more it became known that he wanted to escape observation the more was curiosity aroused to see him, so that a considerable part of his life was spent in adopting stratagems to prevent sight-seers from catching a glimpse of the aristocratic enigma.

The carriage was so made that when the doors were closed no one could see into it, though there were spy-holes arranged that the Duke could look out on all sides and not be observed.

One day the Duke had sent his usual written order for his carriage to proceed by road to London.

The postillions started quite oblivious that they had his Grace with them in his mysteriously-constructed vehicle.

It was a long journey, and as they passed stage after stage, their delays for refreshments became longer and their stoppages more frequent.

They had just pulled up at a country inn when they were horrified to hear a sepulchral voice from the hearse-like chariot shouting,

“What the devil are you stopping for?”

These few words were enough. They came from the voice of the Duke whom they saw not, but recognised by his tones from his tomb on wheels.

The postillions sprang upon the horses and tarried not till they had arrived before the portico of Harcourt House where the great myth descended unseen to his room.

Harcourt House, Cavendish-square, was a famous London mansion, for many years in the possession of the Dukes of Portland. The building of this stately town residence was commenced in 1722 for Earl Harcourt. It had a noble courtyard facing Cavendish-square, and an imposing ports cochere, with a large garden and wide-spreading trees, which were such extraordinary features to be found as adjuncts to the old London palaces of the nobility. Then there was a range of stabling enough to accommodate the stud of a monarch.

This noble mansion was gambled away at a card-party when the stakes were high and the players were the third Duke, grandfather of the eccentric peer, and Earl Harcourt. Thus it came into possession of the Bentincks.

During the occupancy of the fifth Duke, the curious freaks of building for which he was so famous at Welbeck were repeated at Harcourt House. He had the garden enclosed with a gigantic screen of ground-glass, extending for 200 feet on each side and 80 feet high. His object in having this screen constructed was that the residents of Henrietta-street and Wigmore-street might be prevented from seeing into the garden and possibly catching a glimpse of his Grace when taking a stroll.

The gamble for Harcourt House was commuted into a leasehold tenancy by the intervention of the lawyers, who declared that the ownership of the mansion could not be separated from the rest of the estate.

In more recent years the leasehold interest was purchased by the Earl of Breadalbane, and on its expiration, it eventually came to Sir William Harcourt, the statesman, and in August, 1904, was offered for sale. The site of the beautiful garden, with its screen and stables, was purchased by the Post-office authorities. Sic gloria transit of one of the famous houses of London.

Though he had such magnificent palaces, both in Sherwood Forest and in London, the Duke was not given to entertaining guests after the manner of a great noble. His father had sent the family plate to be kept by Messrs. Drummond, bankers, and it was the current belief that the son never had it from the vaults of the bank to grace his tables at Welbeck or Harcourt House.

His sisters seldom visited him, although one of them, Lady Ossington, lived at Ossington Hall, about 15 miles away, in the same county as Welbeck.

The gossips of his lifetime would have it that his pet aversions were tobacco, women, and anyone in the garb of a gentleman; but he had a taste for drinking stout and lived on a simple dietary.

These stories involve a tissue of inconsistencies. His correspondence with Fanny Kemble when he was Marquis of Titchfield, already quoted, shows his kind consideration, not only for her, but for other ladies who moved in higher circles. There was his friendship with Lady Cork, who was often seen by the workmen on the estate driving Shetland ponies. She was a visitor at Cuckney Hall, which was part of the Welbeck domain. Again there are instances on record of his courtesy to those of the opposite sex whom he met in the park; besides which there were many female servants engaged at the Abbey.

“Music hath charms to soothe the savage breast”; but among the other idiosyncrasies laid to his charge, it was said that rather than soothe, it irritated him.

Mrs. Hamilton’s testimony is that Mr. Druce (assuming him to have been identical with the Duke) was extremely fond of music, and that she had played to him for hours at a time.

“Sing me the old songs, Stuart” Druce would say to her father, who not only sang, but played the violin.

Moreover the workmen at Welbeck were allowed to have a band which performed at the Abbey on Christmas-eve and the bandsmen were given refreshments.

What a quaint figure the Duke’s was. When away from home he wore a wig, but not indoors, his tall hat had a broad brim, he wore a white tie and high collar, his trousers tied round his legs, were of check, with a frock coat and dark waistcoat.

His habits were fastidious, and he would not handle bronze or silver coins before they had Leon washed. Then he forbade persons to touch their hats to him if they met him.

His manner of dispensing benefactions was characteristic. Sometimes he was lavish in his generosity, while on other occasions he replied in burning words to those who appealed to him.

An instance of the latter is afforded in his reply to the members of a Friendly Society which was in straits for the want of 10l. He told them that if it was a Club established on sound lines, it would be worth their while to subscribe the money among themselves, and if not, he declined to maintain a bankrupt organisation.

He was a devourer of the contents of newspapers, and took all the principal London and provincial daily issues, as well as many weekly journals, which were filed and bound. His bill for one year came to 1,300l. He had four sets of the papers he thought worth preserving, one being at Welbeck, another at Fullarton House, a third at Bothal Castle, and a fourth at Harcourt House. This collection of current literature of the day is believed to be the largest private library outside the British Museum.

In January, 1855, the Crimean War was in progress, and the Duke having given 500l. to the Patriotic Fund, further showed his bounty by ordering that several fat bullocks, 100 head of deer and 1,000 hares should be potted and sent out to the scene of action. Besides these eatables he gave a quantity of unbleached cotton and flannel to be made into shirts and other garments by the ladies of Worksop and district. In that same month Major-General Bentinck, who had been wounded in the right arm, arrived at Welbeck, intending to return to the war as soon as his wound would allow him.

It was formerly the custom for everyone who paid a visit to the stately home in Sherwood Forest, whether on business or pleasure, not to come away without tasting the Worksop ale. Its quality was renowned, and the Duke sent 1,000 gallons of it to the Army fighting in the Crimea.

The lake at Welbeck is three miles long, and its waters are supplied from an irrigation system at Clipstone, costing the fourth Duke 80,000l. to carry out, draining a tract of marshy land and making it one of the most fertile districts in England. After supplying the lake at Welbeck the stream flows to that at Clumber.

It was estimated that between two and three millions sterling were spent by the Duke in putting his ideas into execution, and the one beneficent effect of his expenditure was the employment of a large number of men in work that was not altogether of a useless nature, as witness his great improvements in agriculture, following up his father's ideas, adding to the national wealth by the crops this hitherto uncultivated area was made to produce.

After his long and chequered career the Duke passed away in December, 1879, having nearly reached eighty years of age. Peace be to his ashes.