< Previous | Contents | Next >

10. Climate and Rainfall.

The average weather of any place is called its climate. This depends primarily upon its latitude. But places upon the same latitude may have different climates owing chiefly to the proximity of the sea. Other less important factors are the direction and strength of the winds, the amount of sunshine, the temperature, and the rainfall.

Most of our weather comes to us from the Atlantic. It would be impossible here within the limits of a short chapter to discuss fully the causes which affect or control weather changes. It must suffice to say that the conditions are in the main either cyclonic or anticyclonic, which terms may be best explained, perhaps, by comparing the air currents to a stream of water. In a stream a chain of eddies may often be seen fringing the more steadily-moving central water. Regarding the general northeasterly moving air from the Atlantic as such a stream, a chain of eddies may be developed in a belt parallel with its general direction. This belt of eddies, or cyclones as they are termed, tends to shift its position, sometimes passing over our islands, sometimes to the north or south of them, and it is to this shifting that most of our weather changes are clue. Cyclonic conditions are associated with a greater or less amount of atmospheric disturbance; anticyclonic with calms.

The Royal Meteorological Society receives reports of the temperature of the air, the hours of sunshine, the rainfall, and the direction and force of the wind from all parts of our islands, and publishes a daily report with a map, which may he seen in almost any newspaper. We can at a glance learn what has happened in other parts of England during the last twenty-four hours. At the end of the year these results are all brought together and averaged, and we can compare this average climate of the different British areas.

In Nottinghamshire there are several stations, well equipped, where records have been kept for many years.

Of all the observations made upon the wind at Hodsock Priory during the thirty years 1876—1905, one-third showed the wind coming from the south-west and west; nearly as many indicated calms; the rest indicated winds coming from other quarters. The prevailing winds of our county, therefore, as of England generally, are from the south—west or west. The latter are most frequent in July, the former in December. Easterly winds are commonest in March.

In 1908, only 1228 hours of bright sunshine were recorded at Hodsock. This was less than the average for twenty-five years, viz. 1252. In the same year the sunniest month was May, with 170 hours of sunshine. The dullest was December, with only 30 hours. Thus the range was from 35 per cent to 13 per cent of the time the sun was above the horizon. These figures are approximately true for the rest of the county, which thus compares unfavourably with the south coast of England and some parts of the eastern counties seaboard. On the other hand it is better off than some of the uplands of Derbyshire and Yorkshire, which have an average of less than 1200 hours sunshine in the year, or than many great cities such as Manchester, where in 1907 only 894 hours were recorded.

On May 20th, 1909, the highest temperature reached in Nottingham was 66° Fahr.; the lowest was 40°. These observations exhibit a range of no less than 26° Fahr. within twenty-four hours. In the Scilly Isles on the same day the range was only 9°, i.e. from a maximum of 59° to a minimum of 50°. This difference between the two places is due to the fact that Nottingham is surrounded on all sides by land, the Scilly Isles by water.

It is well known that if the sun shines with equal strength on land and water, the former becomes heated more rapidly and to a higher temperature than the latter, while, after the sun has set, if the sky is clear, the heat radiates away from the land more rapidly than from the water. These two influences, sunshine and radiation, are most effective in the summer time. In July at Nottingham the average maximum temperature is 70° Fahr., at the Scilly Isles 64°.

Both influences affect the temperature in the winter also, but then the moisture-laden winds from the Atlantic play a more prominent part. They prevent the temperature from sinking as low as it might otherwise do. Here again the west has the advantage, for whilst Nottingham has an average minimum in January of 31° Fahr., the Scilly Isles have 42°. Thus at Nottingham the annual range is 39° Fahr., while that for the Scilly Isles is only 22° .

These facts illustrate the differences between a “continental climate” and an “insular climate.” The latter is characterised by equableness and dampness, the former by cold winters and unusually warm summers. As compared with the climate of the Scilly Isles that of Nottinghamshire is continental. As compared with that of places of the same latitude in central and eastern Europe it is, in common with the climate of the whole of the British Isles, insular. The average temperature of our country is much higher than its latitude would lead us to expect. This is due to the fact that the prevalent south-westerly winds not only come from warmer regions themselves but also cause that drift of warm surface waters of the Atlantic to our shores commonly called the Gulf Stream. These combine to produce our mild winters.

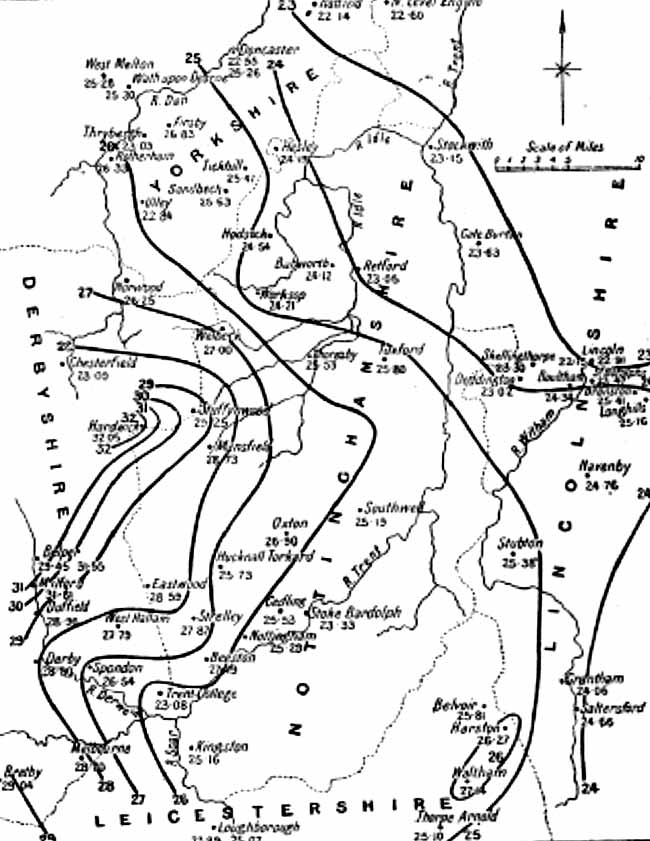

Map showing distribution of rainfall in Nottinghamshire and neighbouring counties.

The amount of rainfall varies considerably from day to day. In 1908 in Nottingham there were 182 days on which it was less than one-hundredth of an inch. The heaviest rainfall, over six-tenths of an inch, was on the 25th of March. The total fall for the year was 227 in., which is equivalent to a downpour of 25,086,152 tons of water upon the city.

The average rainfall during the last forty-two years has been 249 inches. During that period the wettest year was 1872 with a fall of nearly 36 inches, and the driest year 1887, with less than 16 inches.

The accompanying map, prepared by Mr Mellish of Hodsock, shows the average distribution of rainfall in this county for a period of thirty years. From this it will be seen that the rainiest district is the high ground west of Robin Hood’s Hills. It is interesting to note that this supplies the sources of many of the largest streams in the county. The driest district is the lowest ground in the extreme north of the county.

From the general rainfall map of England it will be seen that this county is much drier than counties of the same latitude west of the Pennines. Much rain comes with the cyclones from off the Atlantic. As the air laden with moisture from its passage over the ocean is forced up by the Pennines it expands and cools and consequently discharges much of its moisture there. Passing over the hills the air then descends to the low ground, including Nottinghamshire, on the east. The reverse now happens. The greater part of this county is therefore in the rain-shadow of the Pennines.

What these are to our county the moorland of Devon and Cornwall, the Welsh mountains, or the fells of Cumberland and Westmorland are to the rest of England. This accounts for the fact, well shown on the map, that the heaviest rainfall is in the west, and that it decreases steadily until the least fall is reached on our eastern shores. Thus in 1906, the maximum rainfall for the year occurred at Glaslyn in the Snowdon district, where 205 inches of rain fell; and the lowest was at Boyton in Suffolk, with a record of just under 20 inches. These western highlands, therefore, may not inaptly be compared to an umbrella, sheltering the country further eastward from the rain.

The rainiest month in the year is October, though July and August run it very close. In fact our county is characterised by its summer rains, as about 10 inches out of the annual 25 fall during the months of May, June, July, and August.

The climate of Nottinghamshire may be briefly summarised in the following terms :—the prevailing winds are westerly and south-westerly, the amount of sunshine is moderate, the temperatures comparatively extreme, and the rainfall low with a large fall in the summer. It must he remembered, however, that strictly local factors may exist. An open country or a sheltering range of hills, a southerly or a northerly aspect, a sandy or a cold clay soil will produce striking differences in the climate of places distant only a few miles one from the other.