< Previous | Contents | Next >

The Ancient History of Sherwood Forest

By the Rev. J. Stacey, M.A.

TO the attention of the traveller, approaching the village of Ollerton, in Nottinghamshire, from the north, a scene of no ordinary interest and sylvan beauty presents itself.

There he will behold around him, on every side, an assemblage of venerable oaks, some indeed retaining much of their pristine vigour and comeliness, but more with their heads dead and blanched, their ample boles hollowed, and shewing every stage of decripitude and decay, and giving plain indications of extreme antiquity. As these are found in an apparently unenclosed state, and are interspersed with abundance of furze, heather, and ferns, with other wild sylvan accompaniments, he will feel as though he were within the precincts of an ancient forest. And such is truly the case, for he is passing through a portion of the wood of Bilhagh, which with its sister wood of Birkland, adjoining it to the west, together covering nearly 1500 acres, formed part of the celebrated Forest of Sherwood, which once included within its precincts a great portion of the central part of the county of Nottingham.

And when we mention the name of Sherwood, what visions present themselves to our minds of bold Robin Hood, Little John, Will. Scarlet, and their lawless associates, and their various adventures with the sheriff of Nottingham and others, so dear to our forefathers of many a generation, in legend and ballad; one version of which, under the title of "Lytell Geste of Robyn Hode," from the press of Wynken de Worde, forms one of our earliest printed books; while we find the subject alluded to as early as the middle of the fourteenth century, in the "Vision of Piers Ploughman," when the character of Sloth is introduced saying,

"I kan not perfitly my paternoster, as the Priest it sayeth,

But I can rymes of Robyn Hode and Randolf, Earl of Chester."

We must, however, check our imaginations on this subject, and turn to a more prosaic and matter-of-fact view of the history of this Forest of Sherwood. Though we cannot but here enter our protest against the sceptical spirit of the present day, which has led many to doubt the very existence of Robin Hood, and to treat the long-cherished traditions of him as no better than myths. For there seems no reasonable ground for doubting that what has been so early and so generally believed must have had some substantial foundation, though we are by no means called upon to give credit to all the exploits which we find attributed to this celebrated outlaw. Many of these, no doubt, if not entirely inventions, put forth to embellish and to excite interest in a story already current, are probably to be attributed to other persons of after ages, who have in their general character and deeds borne a resemblance to some real and eminent prototype; as we know to have been the case with most of the heroes of antiquity. This view of the subject seems to derive considerable confirmation from the designation given to marauders of that stamp in general, in our ancient laws and other documents where they are denominated "Robert’s men."

In the British period we have no particular records of the state of this district. It formed part of the residence of the powerful tribe of the Coritani, who inhabited the midland counties of Northamptonshire, Leicestershire, Rutland, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, and Lincolnshire. And doubtless at that time great part of the district was covered by a dense primeval forest, well adapted to the wants and habits of a people who lived chiefly by the produce of the chase.

During the Roman occupation of our island, it is evident that this district was well known to that people. Various Roman camps have been discovered in different parts of the forest of Sherwood. These would, no doubt, be found necessary to keep in subjection the warlike inhabitants, who from their sylvan coverts would be ever ready to make incursions on their foreign invaders.

At the latter end of the last century, Major Hayman Rooke gave to the Society of Antiquaries an account of several of these camps: he mentioned, for instance, one at the west extremity of the county near Pleasley Park, 6oo yards in length and 146 in breadth, of pretty regular form, with its ditches remaining; another, which he considered an exploratory camp, near the east end of his own village, of Mansfield Woodhouse, on an eminence called Winney Hill; a third in Hexgrave Park; a fourth at a place called Combs, near the same neighbourhood, where Roman bricks have been frequently dug up. He also mentions other camps at a place called "Oldox," i.e. probably "Old Works," near Oxton, and at Berry Hill.

Major Rooke also discovered the remains of two extensive Roman villas, a mile or so to the west of Mansfield Woodhouse. These were very near each other: the one he considers to have been a "villa urbana" or residence of some Roman officer of distinction; the other a "villa rustica" or farm house belonging to the superior mansion. We may well suppose that this site was selected for the purpose of enjoying the pleasures of the chase, of which we have clear indications in the antlers of deer which were found among the ruins.

A Roman road also appears to have crossed the Forest, branching off from the great Foss Way, probably at the station named "Ad Pontem," in the Antonine Itinerary, which is supposed to have been situated at Farndon, near Newark. It passed through or near Mansfield, where Roman coins have been found, and so by the camp near Pleasley Park to the neighbourhood of Chesterfield, when it would join the road leading from Derventio or Little Chester, near Derby, to the north.

As regards the Saxon period we have little knowledge respecting this district, except as we may gather from the Domesday survey, that various settlements had been formed within its precincts, many of which, as Mansfield, Edwinstowe, Warsop, Clune, Carburton, Clumber, Budby, Thoresby, and others, are there set down as having belonged to King Edward the Confessor, and as having afterwards become the property of the Conqueror.

It is worthy of observation, however, as regarding the Saxon times, that the great battle in which Edwin the first Saxon King of Northumbria was slain, when fighting against Penda King of Mercia and Caadwaller King of Wales, most probably took place, not as has been generally supposed at Hatfield, near Doncaster, but at Hatfield in this neighbourhood, and that his body was buried at the village near this place, which from that circumstance derived its name of "Edwinstowe, or the place of Edwin." Such, at least, was the opinion which the learned Abraham de la Pryme, who being a native of Hatfield, near Don-caster, and very zealous for its antiquarian repute, was compelled, no doubt, somewhat reluctantly, to adopt.

In the Domesday survey the Forest of Sherwood is not mentioned as such, but, as we have already intimated, many places are named within its precincts as members of the King’s great manor of Mansfield. And this circumstance of the crown possessing already so much property here, would greatly facilitate the operation of converting it into one of the great hunting grounds of our Norman sovereigns, who were, most of them, passionately addicted to the chase. It would thus become a royal forest, and be brought under the cruel operation of the forest laws, which punished the least infraction of their injunctions with the severest penalties, even to the loss of life or limb.

The earliest express notice of the Forest of Sherwood occurs in the 1st year of King Henry the II., when William Peverel, the younger, answered respecting the plea of the forest. He appears to have had the whole profit and control of the district under the crown. These lapsed to the King upon the foffeiture of his possessions, and were for some time administered by the sheriffs of the county, in whose accounts they appear, with payments for foresters and other officers, and also with an item of £40 per annum to the canons of Newstead, the well-known monastery within Sherwood.

In the 12th year of the reign of that king, Robert de Caux, Lord of Laxton, a farmer under the crown, answers for £20; and in the i5th Henry II. Reginald de Laci for the same sum, "pro censu forestae" under Robert Fitz-Ralph, then sheriffs In "the Forest book" is preserved a copy of a charter which was granted by John, Earl of Mortyn, afterwards King of England, to Matilda de Caux and Ralph Fitz-Stephen her husband, confirming to them and her heirs the office of chief foresters in the counties of Nottingham and Derby, and of all the liberties and free customs which any of the ancestors of the said Matilda had ever held.

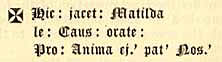

This lady died in 8th Henry III. A.D. 1223, and was buried, it seems, at the church of Brampton, near Chesterfield, where Adam Fitz-Peter her first husband had a manor. There her tombstone was dug up in the churchyard more than a century ago, and is still preserved; on it, the upper half of a figure, holding a heart, is represented in relief, within a quatrefoil, with this inscription:

This is figured in Glover’s "History of Derbyshire," accompanied with an inaccurate account of her family.

In the office of chief forester, she was succeeded by her son and heir, John de Birkin, and he again by his son and heir, Thomas de Birkin, who respectively did homage for their land and for this hereditary office in the 8th and 11th years of Henry III.