Lenton then and now

17th century house on Gregory Street, Lenton (photo: A Nicholson, 2005).

UNTIL 1877 Lenton was a part of the County of Nottingham, and all its history appears in such relation, but in that year an act of parliament was passed whereby it became a part of the Town, now the City, of Nottingham.

Its name was probably derived from the river Leen which flows through it, and tun or tori, which originally meant an enclosed place—a cluster of homesteads.

The western part of the parish has undulating and beautifully-wooded parks, and grounds of mansions, some of the trees being large and fine, while the southern part has extensive meadows in the Trent valley, and the eastern part has been largely cultivated in gardens, which have recently disappeared.

Its Geology. The young people residing in a place ought to know something of the dirt under their feet, and the more so when, as in Lenton, it is interesting and varied.

The late Mr. J. T. Godfrey in 1884 published "A History of the Parish and Priory of Lenton," a book with which every young person in the parish ought to make acquaintance, and the 17th chapter, on "The Geology of Lenton," is by James Shipman, a little man with a big head and a large heart, who under great disadvantages and with limited time and means, gained a more intimate knowledge of the geology round about Nottingham than any other man, and had the greatest pleasure in communicating the information he obtained. Whatever James Shipman wrote may be relied on.

Mr. Shipman gives a geological section from the Tottle Brook on the west of the parish, to the south of Nottingham Park, and another from Wollaton Hall to Clifton Grove. Underneath Lenton there appear to be Coal Measures, estimated at two thousand feet in thickness, which consist of alternations of clay, sandstone, ironstone and coal, and the coal is in many seams, varying in thickness from half an inch to six feet. Once upon a time the surface of the land was where those seams of coal now are. and they therefore contain relics of animals, plants, and other objects. Over all this is deposited Lower Mottled Sandstone, as may be seen near Spring Close; Bunter Pebble Beds, near Lenton Firs, and best shown in Nottingham Castle Rock; Keuper Water Stones, and Marl as it is near Highfield House; but there is visible in Cut-through Lane, east of Lenton Hall, a fracture, where what is called the Clifton fault brings the Marl against the Pebble beds. In other words, the seams on the southern side are sunk ninety-six yards lower than on the northern side, and this forms a wedge nearly a quarter of a mile in width.

The exposure of the rock in the fields east of the Hall was occasioned by excavations for the Midland Railway.

There are also in the Trent Lane district traces of an ancient lake, with more than ten feet of blue clay and soil, and with fine silt and sand mixed with plant remains of weeds and rushes, and gravel below.

The coal under the southern part of the parish is being extensively won by the Clifton Colliery Company, at a depth of 265 yards. The land may, if all the coal is extracted, sink below the present water level.

There have been not only deposits, but what is called denudation, for all the Trent Valley has been washed away from a much greater height than it now is, to a much greater depth than now appears, and there are in some places terraces of twelve feet of ancient gravel, and in others ten to twenty-five feet of recent river gravel and silt.

The Leen Valley also has its record of Glacial Drift, when Arctic conditions prevailed here, and glaciers descended slowly to the coast, and the land was alternately raised and submerged. In excavating for the foundation of the Riding School on Faraday Road, Messrs Brewill & Baily found that eleven feet of loose sand had to be passed through before reaching the gravel, and in the Lower Mottled Sandstone at Spring Close Mr. Shipman found traces of the deposit high up on a terrace "much kneaded and contorted apparently by the same force that crumpled the gravel and sand by the Leen at Cobden Park, higher up the valley."

Saxon Days. We must now leap over the vast ages. Mr. Godfrey gives (page 11) a picture of a fine perforated stone axe, found on the sand hills in Wollaton Park—a relic of the Stone Age. Some Roman articles have been found here, but nothing to constitute a claim to a settlement. The Angles came up the Trent, and doubtless made a settlement, and cultivated parts of the parish in probably three fields, but without hedges, every householder having strips in each of the three fields. There would be tofts, or cottage enclosures, the houses being built of wattle and daub, and covered with reeds or thatch. Part of the land would be meadow, on which cattle grazed in common, part would be wood or thicket, and part waste, but of this we lack information.

Norman. At the time of the Conquest Unlof, the Saxon, had the Manor of Lentune, which was then given into the wardship of William Peverel, who allowed Unlof or Ulnod to continue as tenant. There was a mill on the river, and ten acres of meadow, and ten of underwood, but the value was very small, being only ten shillings (equal to £15now).

Morton. There was, according to Domesday book, a Manor named Mortune, where Bovi, the Saxon, had land, which was given to William Peverel, and by him presented to Lenton Priory, but Mortune is lost, and is supposed to have been in the locality of Dunkirk farm.

Keighton. Another village called Keighton, or Kirkton, is said to have occupied the site between Spring Close and Highfield Park, near Cut-through lane. Here, in 1387, the houses belonging to the prior were stated to be "as much in want of repair as of tenants."

The conjunction of the big sand hills at Spring Close, near by here, the old name of Kirkton, and the more modern one of Dunkirk (or the church of the dunes —or sand hills) is worthy of note. If the name is modern, then there may be an allusion to some engagement off Dunkerque, in France.

Bestwood. Bestwood Park was for centuries claimed by Lenton as being in its parish, the slender threads of right being that Henry I. (1100-1135) during his stay in Nottingham Castle granted the right to Lenton Priory to fetch two carts of dead wood and heather out of the royal forest of Beskwood, and Henry III. (1216-72) made a similar grant, giving the monks the right of daily wandering in the hay of Boscwod.

Southwell. The Priest and Churchwardens of Lenton, in accordance with the Pope's Bull of 1171, went each Whitsuntide to Southwell to join in the great procession, and took with them 2s. as Pentecostal offerings from the parish, (equal to 50s. now).

The Leen. By the banks of the Leen William Peverel decided to build a monastery of the Cluniac order, at a spot within sight of his Castle, and where there were in triangular directions beautiful views of the valleys and hills. Probably the little river was then well stocked with fish, and therefore would supply food and pastime for the monks, but it has had an unfortunate experience. Then a silvery stream flowing from Hollinwell hills, and for centuries grinding the corn at the mills of the lords of the manors as it passed down the valley, until it entered the Trent opposite Wilford Church, and formed the western boundary of Sherwood Forest, it had its course diverted (possibly by William Peverel shortly before the Priory rose) to near by Nottingham Castle, beyond which it afterwards became a stream polluted by tanners and bleachers, and ultimately flowed into a sewer. Later still its course was cut short by being turned into the canal. Coroner Browne used to say that he had known the Leen as a trout stream, and had caught many fish.

A. E. Cooke wrote :—

"Not so of old, from Newstead's cloistered shade

By Linby's holy crosses twain it stray'd Famed

Radford's Folly left with pious haste And stately

Lenton's gorgeous fane it passed."

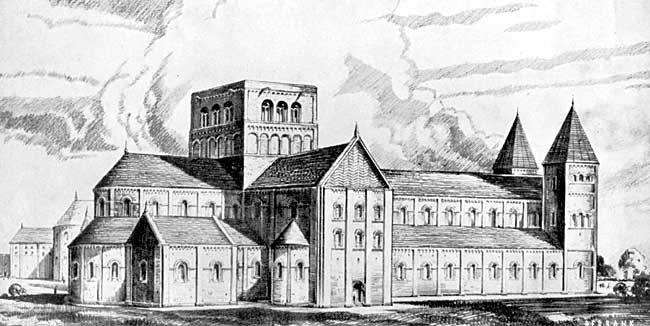

Reconstruction drawing of Lenton Priory.

The Priory. The glory of Lenton was in those days its Priory, the chief building of which was the Church. All that wealth and art could produce in design, construction, and decoration, would, notwithstanding original simplicity, here be brought together, to form a Temple for God ; not merely a house of assembly, in which people could gather and worship, but an offering to God worthy of His acceptance, and as the grand cathedral must be what King David calls "exceeding magnifical," the priory church must be such in miniature, and therefore have all that skill could devise in richness of window and doorway, in carved arch-moulds, in wealth of zig-zag lines, in pillars with elaborate capitals, in sculpture, enamel, marble, mosaic, ivory, gold, silver, and bronze, in painting and glass to adorn the high altar, the transepts and nave, with aisles, Lady Chapel, and numerous smaller chapel altars, chapter house, auditorium, refectory, kitchen, infirmary, almonry, cloisters, library, dormitory, palace and guest-chambers, workshops, and every other requisite

This Priory was richly endowed with enormous possessions of manors and lands, churches and tythes; of mills and fisheries, fines and offerings, with serfs and their children and chattels, and to enforce obedience to law the Prior had a prison, to which ordinary criminals were committed, and from which William Forde, of Duffields, carpenter, charged with felony, in 1505, escaped "in contempt of the King."

For four hundred and thirty years the Priory and its work continued. Its wealth and importance were such that kings lodged here in preference to Nottingham Castle, for here stayed Henry III. in 1230, Edward I. in 1302 and 1303, Edward II. in 1307 and 1323, Edward III. in 1336, and other distinguished visitors, with their retinues, were entertained, and very rare privileges were obtained and conferred.

And then came a time when wealth brought luxury, then indebtedness, inactivity and uselessness. The people were poor, many of their houses were in ruins, and the rulers envied and coveted the wealth, and Nicholas Heath, the last prior, and eight of the monks, and four Lenton labourers, were charged with treason, possibly of conversation only, or in connection with the Pilgrimage of Grace, tried at the Shire Hall, convicted, rightly or wrongly, probably wrongly, and the Prior is said to have been hanged above the priory gateway; the rest were hanged probably on Gallows Hill (Mansfield Road), and their bodies drawn and quartered, and dragged round by Cow Lane (now Clumber Street), and all the property was confiscated to the King. The lead was stripped from the roof and taken to Nottingham Castle, and thence to London, and Lenton Priory was left in desolation.

A column base is all that remains above ground of Lenton Priory church.

What Good? We may admire the motive of William Peverel in founding and so largely endowing the Priory, and appreciate the piety of men and women who in succeeding generations gave of their substance to maintain the institution. We may admire its architecture and decorations, and denounce the spoliation, but still we are tempted to ask, what good was accomplished by all this display? Vast possessions, and endless time were devoted to prayers for the dead, but were there corresponding efforts for the salvation of the living? The burden of sin sat heavily on the consciences of good men and women in the olden time, and the priests and monks had the message of life and peace from the Great Burden Bearer. Did they convey it? Was Lenton Priory a centre of light, and life, and love, for the surrounding district?

More than thirty priors followed in succession, and usually with twenty-four to thirty monks in residence there must have been a total—in over four centuries—of one thousand men. Were there any that stood head and shoulders above the rest in good and useful effort? More than a hundred pages are occupied in Mr. Godfrey's "History of Lenton" with the descriptions of property given and bequeathed. We are told of litigation over property extending, with certain intervals, over three centuries, during which there were five appeals to the Roman Court. Was it good for the national well-being that thirty men who had individually vowed poverty should collectively own such vast possessions ?

Are we judging them by a wrong, or by too high a standard? Those were the days of outward turmoil and danger, and men sighed for rest and quietness,

"Where peaceful rivers, soft and slow,

Amid the verdant landscape flow."

We have now gone to the opposite extreme, and must have energy and work, which is developing into rush. Perhaps both classes had better go back to the Great Example, who did good with meekness and lowliness of heart, but "went about," and went "doing."