< Previous

‘The late disastrous fire at Snenton’ :

THE STORY OF HUDSON AND BOTTOM of Walker Street

By Stephen Best

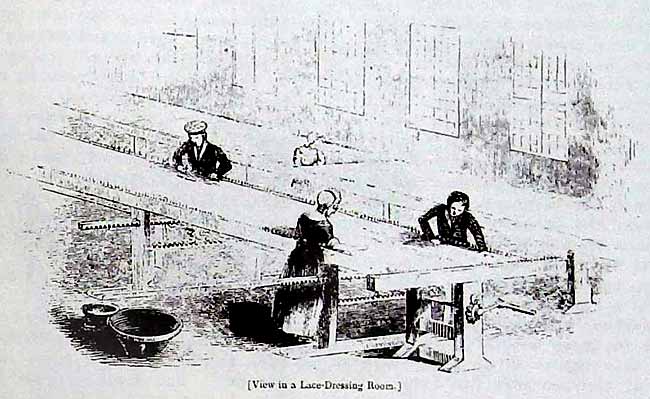

OPERATIVES AT WORK IN A LACE DRESSING ROOM, as depicted in ‘A day at the Nottingham lace manufactories’, published in the Penny Magazine of March 1843.

OPERATIVES AT WORK IN A LACE DRESSING ROOM, as depicted in ‘A day at the Nottingham lace manufactories’, published in the Penny Magazine of March 1843.In September 1832 the Nottingham lace dressing firm of Hudson and Bottom moved the short distance from Herbert Street to Walker Street, Sneinton. Whatever prompted the owners to seek new accommodation, it cannot have been the age of their premises. Herbert Street, which lay between Manvers Street and Carter Gate in the area now occupied by the City Transport bus garage, had existed only since the 1820s.

Walker Street was at that time still in the course of being developed, and a conveyance preserved at Nottinghamshire Record Office shows that on July 19th, 1832, Miss Maria Hudson and Mr. John Francis Bottom purchased from Mrs. Dorothy Walker a piece of land 'bounded to the south west by land set out by the same Dorothy Walker as and for a new street to be called or intended to be called Walker Street'. This property lay between Walker Street and what is now Dakeyne Street. A mortgage document drawn up a short time afterwards refers to '28 dwelling houses or tenements with the large and extensive Lace Dressing or Getting Up Rooms running over the same which have lately been built by the said Maria Hudson and John Francis Bottom', and goes on to state that these houses were not yet completed. A plan of the site included in a conveyance dated May 10th, 1852 indicates that these houses lay back from Walker Street, behind the row of buildings fronting the thoroughfare. These latter included Henry Snowden's baker's shop and the Greendale Oak public house. Hudson and Bottom's twenty-eight houses were reached from the street by a narrow passage and were divided into two terraces, one of sixteen houses, the other of twelve. The Nottingham & Newark Mercury described Hudson and Bottom's lace dressing rooms as 'a long row of high rooms, which are situate on a rising ground near to the Lunatic Asylum, and underneath which are twelve or fourteen houses'. In the light of this report it is possible that only one of the two rows had lace dressing rooms above it. The neighbouring General Lunatic Asylum had been opened in 1812, occupying extensive premises close to where the top of Dakeyne Street is now. When Saxondale Hospital came into use in 1902, the last patients were moved out of the Asylum, much of which was demolished soon afterwards. A remaining part of the building became Dakeyne Street Lads' Club, while a portion of the grounds was turned into King Edward Park.

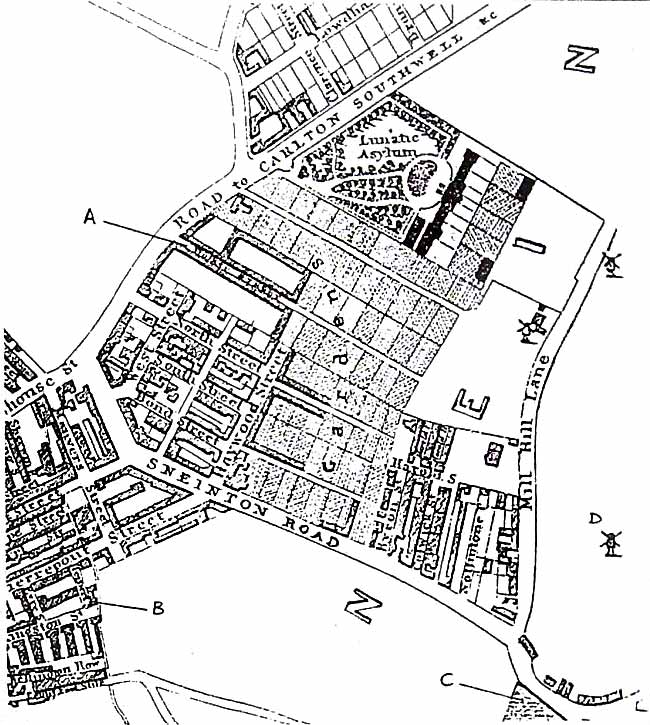

PART OF SNEINTON in the early 1830s, from Staveley & Wood’s map of Nottingham. A...Walker Street: B...Herbert Street (from where Hudson & Bottom moved): C...Sneinton Churchyard: D...Green’s Mill. The map shows how Walker Street then lay on the very edge of the built-up area.

PART OF SNEINTON in the early 1830s, from Staveley & Wood’s map of Nottingham. A...Walker Street: B...Herbert Street (from where Hudson & Bottom moved): C...Sneinton Churchyard: D...Green’s Mill. The map shows how Walker Street then lay on the very edge of the built-up area. Contemporary accounts give a clear idea of what life in a nineteenth century lace dressing establishment was like. Lace dressing was the cleaning, drying and stretching of the brown net fabric to ensure that the individual meshes assumed their proper shape, and that the lace attained its correct final dimensions. The work was carried out under high temperatures, and the workers were exposed to the hazards of the bleaching agents and the sharp edges of the bleached net. Giving evidence in 1841 to the Children’s Employment Commission the Nottingham surgeon Booth Eddison painted a grim picture. 'In 'the getting-up rooms', where the plain net is finished for the market, the temperature is very high; the effect of this is to induce a precocity in the young girls employed, and excessive menstruation. As the atmosphere is dry in these rooms, as well as hot, after some years’ continuance of labour in them, the young women suffer from a peculiar dryness of the mucous membranes, and especially of those of the nostrils and throat; this affection is incurable except by a change of air. The sudden change from this high temperature to the common atmosphere, causes pulmonary diseases, and predisposes to consumption.' The Commissioners did not interview workers at Hudson and Bottom's, but the evidence given by operatives at another Walker Street lace dressing enterprise, that of Joseph Thornley, is typical. Thornley's getting-up rooms were 'very long rooms, containing frames on which the lace is strained, to be dried after it has been starched: at this establishment the frames are each 64 yards long. The temperature at 4 p.m. is 70°. According to Mr. Thornley's statement the heat varies from 50° to 75°; at night the temperature must be highest, because of the gas-lights'. Samuel Kinder, a boy of 13, stated that his job was 'to carry pieces from the dipping-room to the dressing-room, and help in latter'. His normal summer hours were from 6 a.m. to 7 or 8 p.m. and occasionally until 10, with meal breaks provided. Samuel's set wage was four shillings (20p) a week, with no overtime pay. He could read but not write, and was described as 'subject to colds in the winter: has head-ache'. Elizabeth Miller, who was 19 and pregnant, deposed that 'If the air is damp or wet the windows cannot be opened; this can only be done when the weather is hot, dry and windy; when the windows can be opened it is a great relief. When she is well she does not feel any ways fatigued with 12 hours work'. Her usual hours at Thornley’s were from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., but if pressure of trade required she would start as early as 6 a.m. and finish as late as 10 p.m. Elizabeth Miller's regular wage was 9 shillings (45p) a week, with twopence an hour (less than 1p) overtime. It was stated that she, as girl of 14 or 15, At Mr. Bottom's has worked several times from 5 a.m. till 12'. In the light of such evidence it is instructive to read

the replies furnished by J. F. Bottom to the Factories Inquiry Commission of 1834. He declared that the lowest age at which he employed children was from 12 to 14, but did not reply when asked what was the usual number of hours worked by persons under 21. Bottom did, however, indicate that no minor had worked more than sixteen hours in a day during the previous year. Asked for his views on the reduction of working hours, he observed, 'If restricted to hours we could not execute orders with sufficient dispatch, as we dress lace for various manufacturers, whose business depends on our punctuality to a certain extent'. Mr. Bottom related that the usual temperature in his dressing rooms was from 70 to 80 degrees, and that the highest temperature necessary for any part of the process was from 80 to 90 degrees. To the question, 'What are the means taken to enforce obedience on the part of the children employed in your works?’, he retorted, 'If disobedient they are discharged'.

Perhaps our best description of a lace dressing room appears in a supplement to the 'Penny Magazine' of March 1843. Entitled 'A day at the Nottingham lace manufactories', this article was accompanied by lively illustrations. 'The 'lace-dressing rooms' of Nottingham', we read, 'are sometimes two hundred feet in length... long frames extend from end to end of the shop, capable of being adjusted to any width by a screw, and provided with a row of pins around the edge. The net or lace is first dipped in a mixture of gum, paste and water, wrung out, and stretched upon the frame by means of the pins or studs. While on the frame it is rubbed well with flannels, to equalize the action of the stiffening material, and then left to dry in a warm room. It is to the nature of the solution used that the different kinds of net and lace owe their different degrees of stiffness'.

So the scene is set. Hudson and Bottom settled down in the long rooms above the houses in Walker Street. Business increased over the next few years to the extent that the owners decided to put up a new building. As the Nottingham & Newark Mercury reported, 'Acting under the feeling that a new steam apparatus would enable them to do their work quicker and better, they have lately erected on the north east side another spacious building...' This comprised 'a new dressing room, three stories high, and not less than twenty feet square, and a dye-house and starch room connected with it'. The Mercury report appears to have misquoted the dimensions of this building, since both the Nottingham Journal and Nottingham Review described it as being some twenty yards square, a far more likely size for an industrial building. The new block lay, as the newspapers stated, northeast of the earlier buildings in Walker Street, and closer to Dakeyne Street.

This brand new addition to the Hudson and Bottom enterprise came into operation on May 6th, 1839, and had been in use for just four days when, some minutes after 1 p.m. (the exact time was a matter of dispute), the premises were discovered to be on fire, 'and immediately a great number of persons assembled on the spot in time to see flames issuing out from the windows'. No proper fire-fighting equipment was at hand, and the building had to be left to the mercy of the flames until the arrival of the fire engines As was often the case, the newspapers gave differing details about the time of the outbreak, nor could they agree as to which engine was first on the scene. The Nottingham Journal related that the alarm was raised just after 1 o’clock, and stated that the Nottingham town fire engines arrived about three quarters of an hour later, followed immediately by the engine of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Fire Assurance Office, with whom Hudson and Bottom had, a month earlier, insured the new building. The Journal later corrected this story with the information that the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire engine had been at the blaze within ten minutes of being alerted. (It is, of course, possible that both accounts were true, and that news of the fire was very slow in reaching the firemen.) The Nottingham Review agreed that the fire broke out soon after one, and, like the revised report in the Journal, commented on the speedy arrival of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire engine. The Review added vivid detail: 'the men not even stopping to put on the fire dresses; like the heroes of Waterloo, they went to the scene of action, in their undress'. The Nottingham & Newark Mercury story, in several respects at variance with the other two, put the time of the fire at about half past one, and gave an animated description of the arrival, at twenty minutes to two, of one of the town engines, 'attended however, by only a few of its men, its quick progress being mainly owing to Mr. Samuel Armitage, butcher, of Mansfield Road, who without permission being asked, allowed the men to hook the engine behind his light cart, and whipping his horse up, soon arrived with it at the scene of action'. The Mercury also suggested that the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire engine got to the spot some time later.

Even after the arrival of the fire engines at the burning building, matters were still desperate, since the nearest fire plugs were in Carlton Road at the bottom of Walker Street, too far away for the hoses to reach. a human chain was formed, and along this 'avenue of men' was passed a succession of buckets, tubs and other utensils filled with water. This was poured into the fire engines and played on to the fire. The firemen were quickly up on the roof of the new building, where they could be seen 'venturing their lives in almost every direction'.

As ill-luck would have it, there was on this May day a brisk north-easterly wind which helped the fire to gain a fierce hold. This wind, as the afternoon progressed, increased in strength to something close to gale force, and it became clear before very long that, owing to the extreme violence of the wind, which bore clouds of dust and smoke into the eyes of all present, and caused the flames to lick with fury, all was of no avail, and the devouring element almost had its full sway'. Once it was realised that the new getting-up room and starch room were beyond saving, the fire fighters turned their attention to the danger now threatening the older premises. These were, it will be remembered, a row of houses built in 1832, which accommodated Hudson and Bottom's lace dressing rooms on the top floor. Not surprisingly the occupants of these houses were thrown into panic by the sight of flying sparks being fanned towards them by the wind, and the extreme peril was underlined when blazing embers caused the houses to catch fire in several places. To the confusion of the scene was now added the miserable appearance of men, women and children, removing articles of furniture, bedding, machinery and various descriptions of property, with darkened countenances, occasioned by smoke and dust'. The site, as already mentioned, was a congested one, and water had to be passed from Walker Street along the narrow passage into which were crowded householders and other onlookers eager to see what was going on. Inevitably tempers became frayed when the firemen were obstructed, 'and blows were in some instances exchanged ere the matter was settled'. These older buildings were, in the event, saved by the fire-fighters, two of whom came in for special praise in the newspapers. The Mercury commended the 'daring conduct of a man named Thomas Hunt, attached to the large town engine, who played one of the pipes, and who, owing to his having no fireman's dress on, had several times to fight for the pipe he held, the possession of it being disputed by many; he, however, did not give it up, and played it to great advantage during the time he held it'. The Nottingham Review drew to the attention of its readers the heroism of Mr. Ashcroft, captain of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Fire Engine. 'Ashcroft got a rope round the pipe, and venturing into the rooms, which were so filled with smoke that he could only go on his hands and knees, and with his eyes closed succeeded in hauling the engine pipe up, and by playing, saved the building.' There were by now, according to the papers, thousands of spectators at the scene, who, with the firemen and residents, were almost blinded by frequent clouds of smoke and ashes. A further hazard was that 'the heat conveyed by sudden gusts of wind to a very great distance, become intolerable'.

At three o'clock, 'the roof and greater part of the outer walls, of the new and extensive getting-up room fell, with a tremendous and awful crash'. This collapse left one tall gable-end of the new building, which, 'with the violence of the wind could be distinctly seen for an hour and a half swinging about to and fro in the wind, until near five o’clock it fell, leaving the building one general wreck and ruin'. As if this were not trouble enough, it was also feared for a time that the flames would spread from the dressing room and starch room to engulf the new dyehouse. This Latter building, however, escaped with only superficial damage, in happy contrast to the dressing and starch rooms, which had become 'a mass of ruin happily very seldom seen in this neighbourhood'.

By early evening the fire was out, but one of the town engines remained at the scene in case a further outbreak occurred. This proved to be a wise precaution, the engine being needed at 11 p.m. to dampen some smouldering timbers which had been fanned into flame again by the wind. The night passed without further alarms, until 'morning dawned upon a heap of smoking and blackened ruin'. Contemplating this sight, the Journal reporter was moved to write that, 'Never in so short a period, was so complete a mass of ruin effected as in this instance'. Casualties were mercifully light, considering the ferocity of the blaze and the density of the crowds milling around in Walker Street and Carlton Road. Once again the details varied from paper to paper, but it seems that one man was injured in a fall from a ladder, a young man or woman was badly burned, and a third unfortunate suffered a kick from a horse.

The extent of the damage was believed by the press to be between £2,000 and £3,000: the directors of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Fire Assurance Company met on the evening of the fire to instruct their surveyor to liaise with another acting for Hudson and Bottom, in order to estimate the damage done and to fix a payment. As previously stated, the new building had been insured with the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire office only four weeks before the fire, and it was ironic that although the crew of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire engine had been unable to save 'their' building, they had played a major role in preserving the older lace dressing rooms above the houses. These were insured with the County Fire Office, and all the newspapers voiced the opinion that, under the circumstances, the County Office should offer to pay part of the fees of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire firemen, who, in saving the houses, had rescued the County Fire Office from having to meet a substantial claim. Such a payment should be made to the firemen, felt the Mercury, 'If only as an inducement for persons to exert themselves on another occasion'. The press was also unanimous in believing that had the fire broken out during the night, the consequences would have been far more serious, with 'the destruction of many more thousand pounds of property and a loss, most probably an immense loss, of life'.

Generous tribute was paid in print to members of the Nottingham Watch Committee who had hurried to the scene and 'by their presence stimulated the firemen, and by their exertions aided in extinguishing the flames'. Nottingham’s police chief, William Barnes, together with his officers, was also praised for keeping order and controlling the crowds, but the chief honours went, of course, to the crews of the fire engines, and in particular to Thomas Hunt of the town engine, and to the two captains, Messrs. Ashcroft and Griffin Ashcroft was quite the hero of the hour, being in the opinion of the Review, 'Entitled to the highest commendation for his active exertions, collected manners, and discreet conduct'. The Mercury remarked upon his 'placing himself in the midst of every danger to render assistance'. No such praise was lavished upon the onlookers at the fire: not content with hindering the efforts of the fire fighters, some of the crowd made off with possessions of those Walker Street residents who had carried their goods outside their homes to save them from the flames. Others had exhibited ghoulish glee over the disaster: 'We are sorry to say, we heard expressions of delight and exultation at the catastrophe, and rude jests on the masters, Messrs. Hudson and Bottom, were bandied about; it seemed to us that they could only possess the feelings of a demon, who would triumph in the downfall of another'.

Others unlikely to have been congratulated after the fire were those responsible for installing and running the heating system in the new building. All three newspapers attributed the fire to overheating of the stove and flues, and the Mercury added the detail that this was supposed to have caused the ignition of woodwork in the getting-up room. Evidently the high temperatures which characterised lace dressing rooms could exact a toll of the buildings, as well as of those who had to work in them. There was a mildly comical side to the affair, although the Walker Street rentcollectors could have been forgiven for failing to see the joke. When the tenants of the houses evacuated their belongings, some of those who were in arrears with their rent 'took the opportunity of removing them away altogether, thus taking the opportunity to moonshine in the middle of the day, which they no doubt considered the most fit and least hazardous time'.

We cannot know how long the fire had been raging before some wiseacre observed that May 10th seemed to be an unlucky date for Sneinton, pointing out that it was on May 10th, 1829, exactly ten years before, that the great fall of rock in Sneinton Hermitage had occurred. All the newspapers noticed this 'singular circumstance', the Review remarking laconically that 'the inhabitants of Sneinton will have cause to remember the 10th of May'. It may be mentioned parenthetically that Walker Street's most celebrated resident had died just a month too soon to be able to appreciate this piquant anniversary. This was the poet Robert Millhouse (see Sneinton Magazine No. 6), who died, aged fifty, at his home, 32 Walker Street, on April 13th, 1839.

The directors of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Fire Assurance Co. had shown themselves to be brisk and businesslike by meeting on the evening of the fire to arrange a survey of the damage. They were equally punctual in settling Hudson and Bottom's claim. The Nottingham Journal of June 14th reported that the firm's demand 'for the loss sustained by the late disastrous fire at Snenton, has been promptly and honourably met by the Directors who, after being satisfied on inquiry of the justice of the claim paid over to Messrs. Hudson and Bottom on Saturday last, the sum of E2,O6O. In this instance the office had only received one payment from the insured'. Since the firm had paid only this single premium, perhaps it was only natural that the lace dressers 'expressed their entire satisfaction' with this speedy settlement.

The firm of Hudson and Bottom was not put out of business by the fire, and matters went so well for them that by May 1847 their mortgage was paid off. Two years later May 10th, 1849 went by, so far as one can tell, without untoward incident, and one can imagine the sighs of relief heaved by all concerned at Hudson and Bottom's when they had seen the back of that ominous anniversary. The next event of note, recorded in a further conveyance at the County Record Office, took place in March 1851 when John Francis Bottom purchased Maria Hudson's share of the firm. Mr. Bottom, now sole owner, did not wait long before bringing off another business deal.

This was nothing less than the sale of the concern on May 10th, 1852 to our old acquaintance Joseph Thornley, whose employees had given such graphic accounts of their working lives to the Children’s Employment Commissioners.

Over a hundred and thirty years later Walker Street is a pleasant residential thoroughfare with postwar houses, and utterly transformed from what it was like in the nineteenth century. If you pause, though, at the bottom of King Edward Park and look at the industrial premises in Dakeyne Street, standing prominently above Carlton Road, it is just possible to picture something of. the dramatic scene of May 10th, 1839, when the locality's newest industrial building, which stood close by, fell victim to the "strange havoc" of a 'destructive fire at Snenton'.

There remains to be told the story of Sneinton's third great factory fire of the nineteenth century: one which was said to be the costliest fire that Nottingham had experienced. This must wait for a future issue of Sneinton Magazine.

C. N. WRIGHT : A FINAL POSTSCRIPT

In 'Tales from St. Stephen's churchyard' (Sneinton Magazine No. 20) I told of how I had examined the gravestone in Sneinton churchyard commemorating the first two wives of Christopher Norton Wright. I mentioned the possibility that there was a further inscription on the part of the stone that was below ground, but that I had not succeeded in exposing any more writing.

The recent restoration work in the churchyard has answered this query for once and all. The Wright headstone has been lifted and repacked in the soil, and this operation has revealed that Mary Anne Wright, third wife of C. N. Wright, was also buried there after her death on February 2nd, 1837, at the age of 42. With a truly dramatic sense of timing, the work on this stone was being carried out at the moment of the arrival in the churchyard of Mrs. J. B. Sampson of Surrey, a descendant of the Wright family, who had come to Nottingham with her husband to see the gravestone after reading about it in the Sneinton Magazine.

Further confirmation comes from my friend Geoff Oldfield, who has come upon Christopher Norton Wright's grave in the Church Cemetery in Forest Road. The inscription on this stone refers to the burial at Sneinton of the first three Mrs. Wrights.

I cannot believe that there can possibly be anything further to report on the C. N. Wright family puzzle, but I am quite prepared to be proved wrong.

ALL ILLUSTRATIONS BY COURTESY OF NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COUNTY LIBRARY, LOCAL STUDIES LIBRARY.

< Previous