< Previous

A BED OF NETTLES:

The brief, eventful life of Sneinton School Board

Part 1: 'So excited over a contest'

By Stephen Best

THE REV. VERNON HUTTON, vicar of Sneinton 1868-1884, and a leading personality during the School Board controversy.

THE REV. VERNON HUTTON, vicar of Sneinton 1868-1884, and a leading personality during the School Board controversy. FOR SOME WEEKS in 1875 Sneinton was the setting for a vigorous election campaign, more than a dozen men seeking the votes of local ratepayers for places on the newly- formed Sneinton School Board. The Board's existence was to be short, but lively and productive.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, education for the poor was largely a matter of charity or of private enterprise. Many charity schools were in decline, and privately-run establishments were often poorly conducted, by proprietors with few qualifications, and less aptitude, for the work. The most effective schools were, on the whole, those run by two religious societies, the National Society (Church of England), and the British and foreign (Nonconformist). In 1833 public money was, for the first time, provided for education, a grant of £20,000 being divided nationwide between these voluntary school societies.

Returns made to Parliament in 1833 showed the existence in Sneinton of nine private day schools, of between 14 and 43 pupils. Five of these taught both boys and girls, and two each boys or girls only. Of the fees quoted, the lowest were at Martha Blasdale's School, 3d to 6d (1.5p - 2.5p) per week, and the highest at John Potchett's establishment, 6d to 10d a week. At Potchett's schoolroom, the floor space was insufficient for his 30 or 40 scholars, so the little boys were put 'in a sort of gallery on the walls not unlike a gigantic linnet cage'1 Three of the nine schools stated that they took children of all denominations, while two indicated that their pupils had to be Church of England.

Following the 1833 injection of public money, it was widely recognised that the two societies responsible for National and British schools could not alone cope adequately with the elementary education needs of the community. Many proposals for funding the building and maintenance of schools out of local rates, however, came to nothing because Anglican ratepayers objected to spending rates on schools which did not teach the Anglican catechism, while Nonconformists were unwilling to make financial contributions to Church schools.

In 1870 the Forster Education Act saw Parliament take upon itself the responsibility of ensuring that every child in the country had the chance of going to school. The Act stated that elementary schools were to be built in all districts where sufficient schools were not already provided by religious bodies. These new schools would be controlled by locally elected School Boards, empowered to levy rates to pay for them. The Act itself did not make education compulsory everywhere, but local School Boards could, if they wished, make this compulsory in their own areas. The religious objections were to some extent met by a clause stipulating that religious teaching in the new schools was to be undenominational, based on simple Bible teaching. Parents could, if they so chose, withdraw their children from scripture lessons. The 1870 Act was a landmark, creating a countrywide network of elementary schools; further acts of 1876 and 1880 made for compulsory education of children up to the age of ten, and an act in 1890 rendered this education free for all.

It has been estimated that, by 1870, about two-thirds of children in Nottingham between 3 and 13 were on the books of a school. Many of the remainder probably spent at least a few months in school between these ages. When the School Boards were created, it was argued by many that, so energetic had the churches been in providing school places, the erection of Board Schools was quite unnecessary. Certainly some influential Sneinton people believed this in 1875, among them the formidable young vicar, the Rev. Vernon Hutton. It is through Hutton's Sneinton Church Magazine in particular that we can trace the course of events, and see how local opinion was influenced as the School Board election approached. There were, of course, equally strong views held in opposition to the vicar's, but the magazine offered Hutton a significant platform for his opinions, always shrewdly argued and lucidly expressed.

In 1874 the Government's Eduction Department had collected data from the three public elementary day schools in Sneinton parish. These were the Church National Schools (usually called, simply, the Church Schools) in Windmill Hill Lane, which had been open since 1837, St Matthias' Church Schools in Carlton Road, and the Albion Congregational Schools at the corner of Dennett Street and Herbert Street (soon to be renamed Kingston and Beaumont Streets). The accommodation they provided was as follows:

|

|

CN |

St.M |

AC |

|

Boys |

|

252 |

250 |

181 |

|

Girls |

|

126 |

150 |

94 |

|

Infants |

|

126 |

167 |

121 |

|

Total |

|

504 |

567 |

396 |

|

CN |

= Church National School |

||||

St.M |

= St. Matthias' School |

||||

AC |

= Albion Chapel School |

||||

This amounted to a total provision in Sneinton of 1467 places, which, by the Education Department's calculations, meant that additional accommodation for 580 children was immediately required. Proposed extensions to the National Schools, would, however, provide for 61 children, leaving a residue of some 520 to be catered for by a School Board. The Church Schools were indeed pressing ahead with new buildings, as the Church Magazine reported throughout 1874. Following a very favourable report on the schools by Her Majesty's Inspectors in May, the decision had been taken to extend the school by some sixty places, one stated reason being that 'the parish will have this number less to provide for if a School Board becomes necessary'. Helped by a grant from the National Society, and the generosity of well- wishers, the improvements begun in 1875 were, in the event, large enough for 96 extra children. An advertisement in the May Church Magazine announced that a new 'Middle-Class Department' would open in June, 'which shall supply a thoroughly sound commercial education free from the drawbacks necessarily connected with a large school'. In his 1875 annual address to parishioners and congregation, Vernon Hutton made clear the reasons for his rapid carrying-out of the Church School additions: 'I was anxious to accomplish this before the school-board was formed, as after that step has been taken it will be difficult to raise money for school building.' Hutton was keenly aware that as soon as Sneinton ratepayers had to find money for Board Schools, they would be less able and willing to dip into their pockets to support the voluntary schools. As for the value of School Boards, the vicar was distinctly cool. Pointing out that the order for the formation of the Sneinton Board was imminent, he stressed that the Board was to be created only to make good the deficiency in school accommodation, and that the Church Schools would continue unaltered as long as financial support was forthcoming from friends. Should contributions fail, he warned, the Church School would have to close, throwing the cost of educating several hundred extra children on to the ratepayers of Sneinton. 'It will', concluded Hutton, 'be for the parishioners to say of whom the Board shall be composed. At present we are a very amicable parish, and party spirit seems unknown among us. From all that I can gather we may hope that this state of feeling will continue, and that a Board will be chosen who will carry out the Act in the spirit in which it was passed, and who will be able to keep clear of the disputes which disfigure the proceedings of similar bodies, and at the same time to give a distinctively Christian character to their school.'

On October 16 1875, an Order in Council allowed for the setting-up of Sneinton School Board, the election being fixed for Tuesday, November 9. All registered Sneinton ratepayers, both men and women, were eligible to vote. There were to be seven places on the Board, and each elector would have seven votes. These could be distributed as the voter saw fit; from plumping for one candidate with all seven votes, to giving seven different candidates each a single vote, with any combination of votes in between also possible.

The Church Magazine for November made no pretence of impartiality: 'It is not to be desired that the members of the board should all be of one political or religious party. But we trust that all our readers will do their best to secure votes for those candidates who will endeavour to uphold the present school system and not to burden the parish with unnecessary rate-supported schools. A list of those who invite support on these principles will be published on November 2nd.' As becomes increasingly evident, the vicar, although opposed to the formation of Sneinton School Board, was determined to have a substantial say in its running once it became a reality. A member of a landowning Lincolnshire family, and the grandson, son, and brother of parsons, Hutton was at the time almost 34 years of age. Though he had had some difficulties with his bishop over matters of ritual, and though he was not, by any means, to get his own way on the School Board, he was very definitely a power in Sneinton. As a vigorous pamphleteer on religious topics, he well knew how to influence his readers into changing their minds on important questions. The election was marred for him by a side-issue, totally unconnected with the School Board, over which his opponents sought to make capital out of a problem not of Hutton's making. This was the affair of the 'Vicar's Gardens' in Carlton Road. Some land here belonged to the benefice of Sneinton, and during the time of the previous incumbent, the Rev. W H Wyatt, houses had been erected on it by tenants, without the vicar's consent. It had recently been claimed that the vicar was liable for any repairs needed to these houses, and the diocesan surveyor had confirmed this to be the case. Very reasonably, Hutton contested this opinion, and was accordingly criticised by those seeking any pretext for attacking him. After further enquiry, and 'a meeting of the general body of surveyors', it was concluded that the fabric of the houses formed no part of the vicar's responsibilities. The matter was thus cleared up, but Hutton still found it necessary to write to the Nottingham Guardian, clarifying the situation and defending his actions.

As the final list of candidates took shape, Sneinton was seized by election partisanship. It is appropriate at this point to look at the sixteen men whose names were to appear on the ballot paper. Vernon Hutton of course stood for the Church party, in favour of voluntary schools, as did John Webster of Belvoir Terrace. The latter was a leading Sneinton resident: a retired lace-dresser, and for decades a churchwarden. A third candidate was Henry Smith Cropper of Colwick Road, a printing machine manufacturer at Hockley Mill, Woolpack Lane. Cropper was described as an 'Independent Voluntarist', or 'Independent Liberal'; that is, he represented no formal faction, but, as a stalwart support of the Albion Chapel and its day schools, could be expected to fall in behind the vicar on matters of school policy. Two other candidates worked together in the election; George Marsh of Holly Gardens was managing clerk to the Builders' Brick Co., while Thomas Stevenson, blacksmith, of Dale Street, had served in most areas of Sneinton public life, as parish constable, overseer, and on the Local Board. Some reports categorised Marsh and Stevenson as Churchmen, but others linked them with the Unsectarian candidates. In the event they were to combine with the latter to form a working majority on the School Board. There were four Unsectarians. William Burgass, of Brentcliffe House, Carlton, was managing director of Nottingham Brick Co., and a member of Sneinton Local Board and of the Leen Valley Sewage Scheme. Alfred Collishaw kept a grocery shop in Sneinton Road, while Edward Wood of Belvoir Terrace was a lace manufacturer in Plumptre Street, and for many years secretary of Nottingham Sunday School Union. George Allcock, farmer, baker and flour dealer, owned property in John street (later Keswick Street) and Dale Street. The other candidates, who stood as Independents, were James Whitehouse, manager of the Builders' Brick Co., Carlton Road: Edward Charles Buckoil, physician and surgeon of Minerva Terrace, Sneinton Road: Thomas Goodall, also of Minerva Terrace, who had a smallware shop in Goose Gate: William Donner, shopkeeper, of Robin Hood Street: and finally Samuel Eyre, coal, hay and straw merchant, of Sneinton Hermitage. A noted horticulturalist, Eyre had served as chairman of Sneinton Local Board. The remaining candidates withdrew just before election day, too late for their names to be removed from the ballot paper. Of these, Thomas Martin Foster was a maltster and hop merchant, of Thorneywood Lane, while the Rev. Isaac Raine was curate of St Luke's, Carlton Road. Raine's stay in Sneinton was a short one, and he subsequently acted as district secretary of the British and Foreign Bible Society, first in Lincoln, then in Nottingham. One cannot help wondering whether Raine's retirement from the contest could have been prompted by suggestions that, as a Church of England clergyman, he might split the votes which would otherwise go to his near neighbour, the vicar.

It is not known whether any of the candidates was a Roman Catholic, but Catholics would often put up a single candidate at School Board elections, asking their supporters to plump all their votes on him. They were thus sometimes able to secure a place for a Board member who would further the Roman Catholic interest.

William Burgass, a brick manufacturer, and Sneinton School Board's only chairman.

William Burgass, a brick manufacturer, and Sneinton School Board's only chairman.The election campaign did not pass unnoticed by the Nottingham newspapers. On October 29 a meeting of friends of Marsh and Stevenson was held at the Crown Inn, Carlton Road, while on the same evening Unsectarian candidates were selected at the Albion School Room. One interesting man chosen at this meeting later dropped out; Charles Hawley Torr of Notintone Place was an accountant, assurance and estate agent, and local secretary of the RSPCA. The Unsectarian meetings were particularly well covered by the Nottingham Daily Express, which supported their cause. On November 4, once again at the Albion School Room, 'a numerous attendance' heard the candidates speak. William Burgass stated that he was standing only because friends had pressed him, and because he wanted to see every child in Sneinton receive a thoroughly good, sound, unsectarian education. He knew about Board Schools, having been on the committee of Bath Street Schools, the first built by Nottingham School Board, and believed that the expense of maintaining them was 'no great bugbear'. He warned his audience that if Sneinton School Board failed to provide the necessary accommodation, then the Government would declare the Board to be in default, dissolve it, themselves elect a new Board, and take the action required to put up a Board School. It was, therefore, 'mere moonshine' to argue against the erection of a school; what was needed in Sneinton was a Board of local men who would put up a building at the lowest possible cost to electors. Burgass insisted that he and his colleagues had avoided the use of personal attacks in the campaign, but he felt obliged to refute 'some extraordinary statements' by H S Cropper. This candidate was alleged to have frightened voters by suggesting that the Unsectarian group would exclude the reading of the Scriptures in a Board School, but Burgass said he knew of no candidate who would support such a position. Another speaker, John Walker, warned electors that, 'if they returned Mr Cropper, they did not return a man who would do them good. He might be a man of some education, but they wanted a man who was straightforward in his principles....'. Alfred Collishaw also had a few sideswipes at Cropper, though referring to him only as 'a certain candidate'. Of Cropper, Collishaw asserted that 'One day he was a Liberal, another day an Adullamite2, and then a Tory'. Not only this, but Cropper had attended 'hole and corner meetings at the rectory' [sic] for the adoption of church candidates and had himself been proposed by a Sectarian - the master of the National Schools. Collishaw proclaimed himself as all for unsectarian education; he believed that, in National Schools, clergymen 'liked to get hold of the young boys' at an age when they were particularly open to religious influences. As a rule, he asserted, clergy had always been opposed to reforms, and he did not like to see them serving on School Boards; he thought they had other work to do. Collishaw went on to state that, while he was in favour of the reading of the Bible in Board Schools, he was opposed to the teaching of creeds and dogma to children. Edward Wood's 'lengthy and earnest speech' followed, and included a tilt at Mr Hutton. The Unsectarian candidates, said Wood, would fight the contest in a manner of which they need not feel ashamed. It was not their intention to follow the example of the vicar, and hold School Board election meetings in public houses. For a group whose leader 'desired to avoid the slightest personal attack', and 'had not uttered a word to excite the feelings of any one', the Unsectarians had had a lively evening.

On the following day the same party met at Thorneywood School Room. Edward Wood told his hearers that he was sorry that the High Church was so strongly against unsectarian education, but glad that Low Churchmen had shown sympathy with it. Wood had, however, some humble pie to eat - having discovered that the vicar had not been present at the meeting in the pub, he proffered his apologies for having accused Hutton of doing so. He hoped that the Unsectarians would carry the poll, and that William Burgass would be elected chairman of Sneinton School Board.

The campaign reached its climax on the evening of November 8, at a meeting at St Matthias' School. This was chaired by the vicar of that church, the Rev. F A Wodehouse (uncle of the creator of Bertie Wooster and Jeeves), who asked each candidate to speak, and requested for all the speakers 'a fair, and as far as possible a quiet hearing'. The Nottingham Guardian report did not record the comments of Buckoll, the first to address the meeting, and Burgass, who followed him, was content to repeat the sentiments expressed by him on November 4. Next was Alfred Collishaw, once more in trenchant vein - he appears to have been a true Sneinton stumporator of the sort personified fifty years later by Alderman Billy Green. Collishaw described himself as a plain man, 'always in the habit of calling a spade a spade, and not an agricultural implement'. He wished boys to be able to write a letter that would not disgrace a statesman, and also wanted a ratepayer's school, not one under the thumb of Dissenting minister, Church of England clergyman, or 'Romish priest'. These swingeing anti-clerical sentiments were received with cheers. He ended by assuring his listeners that he would never vote for compulsory education unless they had ratepayers’ schools. H S Cropper followed with a lengthy speech; there was, he thought, enough school accommodation in Sneinton already, and the School Board would, in his view, be a burden. Cropper was succeeded by William Dormer, making his only appearance in this account. Declaring that he was a working-man, Dormer told his audience that 'He had not been stumping the parish by any clap-trap or any other trap, with a view to obtaining their votes'. The Guardian summed up his speech with withering brevity: 'He then gave an account of his life, with a view to show his adaptability for the office'. Thomas Goodall stood up next, as 'an economist and ratepayer'. He took an independent course, he said, and would not be bound by any party. Like Collishaw, he referred darkly to 'various hole-and-corner meetings held'. The Rev. Vernon Hutton then offered the hope that the election would be carried through 'as it had begun, in the best of humours', and that when it was over, they could all unite on the friendliest terms. Contrary to rumour, stated the vicar, he made no attempt to persuade children attending the Church Schools to come to Sunday School; he wanted his hearers to know that some of his best friends in the parish were parents of Church School children who were not Sunday School attenders. The final speakers of the evening were John Webster and James Whitehouse, the chairman then asking whether any ratepayer present wished to ask a question. What ensued was a spectacle not unknown at Sneinton meetings even in recent years: A tumultuous scene then followed, in which all attempted to speak at once, and order had not been restored when the meeting broke up.'

Hutton would have found little to please him in two of Nottingham's morning papers of November 9 1875, the day of the election. The Daily Express underlined its endorsement of his opponents with a short editorial, urging Sneinton voters 'to take care that only those candidates are elected who will see that this school is conducted on the broad principles of religious liberty'. They should, thought the Express, 'therefore vote for the Unsectarian candidates, who have no selfish purposes to serve, and no sectarian dogmas to propagate at the expense of the community. By electing the Unsectarian candidates they will secure an efficient education for the children of the parish based on Scriptural principles instead of human dogmas.' This was fair comment, by press standards, but far more unpleasant was a muck-raking letter to the editor of the Nottingham Journal. Its writer, who did not have the courage to put his name to his opinions, mentioned a current controversy about the hearing of confessions at Sneinton church, and, referring to the vicar, asked: 'Is a Ritualistic perverter of the doctrine of the Church of England a proper person to be on a School Board, having the control of the education of our children?'

The papers gave a lively account of election day; for the reader accustomed to the drab apathy which frequently characterises local elections nowadays, the picture conjured up is a very animated one. Said the Journal: 'Within the recollection of any living man Sneinton has scarcely ever been so excited over a contest as it was yesterday. All sorts of statements had been flying about and rumours floated'. The Daily Express reported that 'the parish has been canvassed most energetically by the supporters of the candidates, whilst the election squibs and attacks by either party or the other have been employed to no little extent. Election placards and posters have been scattered over the walls of the parish with no sparing hand'. The Daily Guardian witnessed considerable activity throughout polling day, with crowds gathered outside the polling stations, 'eagerly discussing the merits of the candidates'. The Guardian was glad to note that 'in every instance, however, the crowds were very quiet, their differences leading to no disorderly or unseemly riots in the public streets.' The Journal reported that on the morning of the election, the Rev. Vernon Hutton, despite the 'Vicar's Gardens' controversy, was clearly the leading candidate, 'and that his man Friday, Mr Webster, was upon his heels. Mr Cropper was also wonderfully popular amongst the people, but beyond these nobody was spoken of in particular.' Polling took place from 9.00am to 4.00pm at the three public elementary schools in Sneinton, and at Sneinton Public Offices in Hermit Street. Presumably ratepayers who were at work all day had to register their votes during their dinner-time.

The ballot boxes were all taken to the Public Offices for the count; this did not begin until 5.30, and it was half-past-eight when the result was declared, and a personal triumph for Hutton and his voluntary school supporters hailed. The votes were cast as follows: Vernon Wollaston HUTTON 1939; John WEBSTER 1125; Henry Smith CROPPER 1058: Thomas STEVENSON 890: George MARSH 676: William BURGASS 662: Alfred COLLISHAW 650. These seven were elected to the Board, the unsuccessful candidates (with number of votes) being: - George ALLCOCK 625: Samuel EYRE 556: Edward WOOD 552: Thomas GOODALL 371: Edward Charles BUCKOLL 327: James WHITEHOUSE 317: William DORMER 75: Thomas Martin FOSTER 14: Isaac RAINE 7.

As the two last-named had announced their retirement from the election, it may seem surprising that they received 14 and 7 votes respectively. These could, however, be accounted for by just three electors, unaware of the candidates' withdrawal, each plumping all their votes on Foster or Raine. Of the other unelected candidates, only Dormer put up a disastrous show; his autobiographical address to the ratepayers had evidently failed to impress Sneinton people. Supporters of Wood, Eyre, or Allcock would all have had good grounds for feeling that an excellent man had been rejected.

The Nottingham Daily Express gave the most accurate reading of the significance of the result, reporting that four Unsectarian candidates, one independent Liberal, and two Churchmen had been returned. The first group consisted of Burgass, Marsh, Stevenson and Collishaw; the independent was Cropper, and the churchmen of course Hutton and Webster.

The Journal failed to assess the position correctly, the main problem being that the press found it hard to predict how Marsh and Stevenson would act on the Board. In its list of results, the Journal had them with the Voluntary party of Hutton, Webster, and the independent Cropper, while Burgass and Collishaw were described as 'Dissenters'. The Daily Guardian was even wider of the mark, listing Alfred Collishaw as a Churchman; evidently no one at the Guardian had bothered to listen to, or read, any of Collishaw's speeches.

Unsurprisingly, the Sneinton Church magazine for December expressed satisfaction at the outcome. Reviewing the campaign, the vicar reflected that as many election posters had appeared on Sneinton's walls as would have been pasted up at a Parliamentary election. He also commented on the fact that the fight had not been along purely party lines, but one feels that he had his rose-coloured spectacles firmly in place when writing that: 'It had the great advantage of rendering the election very free from feelings of personal opposition, each candidate pressing his own claims without appearing in special opposition to any of the others'. The vicar paid tribute to the volunteer canvassers who had given up a day's work on election day to get voters to the polling stations. He lamented, however, the loss of votes caused by 'the negligent way in which the rate-book had been kept', it being claimed that a number of would-be electors had been turned away because their names were not listed. We hope', stated the magazine, 'that all our friends will see to this in the future, and will request their landlords to have their names entered properly upon the rate-book'.

(In Sneinton Magazine 51, part 2 of 'A Bed of Nettles' will relate how, despite frequent disagreements on Sneinton School Board, a fine new school came to be built).

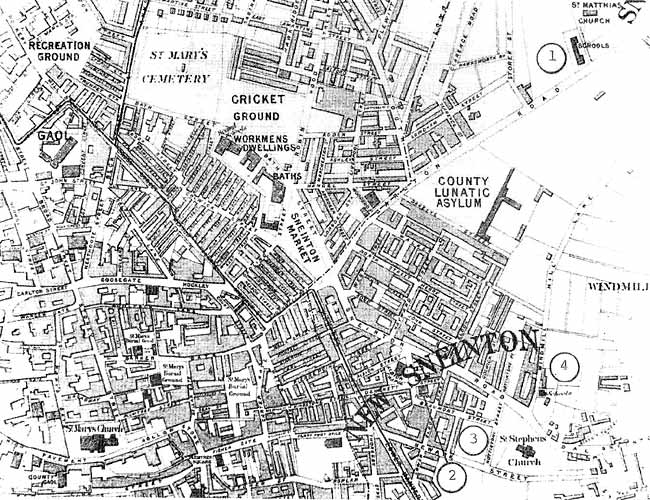

PART OF TARBOTTON'S MAP OF NOTTINGHAM, 1877, showing

PART OF TARBOTTON'S MAP OF NOTTINGHAM, 1877, showing1. St Matthias' Schools: 2. The Albion Day Schools: 3. The site of Sneinton Board School: 4. Sneinton Church Schools.

1. Quoted by PJ Cropper in his Manuscript notes on the History of Sneinton.

2. A Whig seceder from the Liberals.

< Previous