< Previous

SIX HUNDRED YEARS OF THE PLUMPTRE HOSPITAL:

Pt. 1: A very inconvenient and unwholesome habitation

By Stephen Best

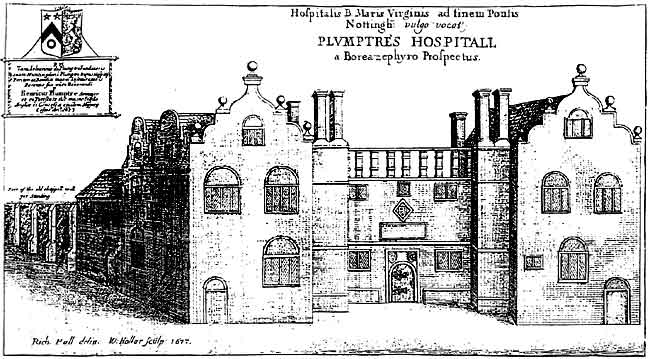

THE PLUMPTRE HOSPITAL after Huntingdon Plumptre's rebuilding of 1650, from Robert Thoroton's 'Antiquities of Nottingham.'

THE PLUMPTRE HOSPITAL after Huntingdon Plumptre's rebuilding of 1650, from Robert Thoroton's 'Antiquities of Nottingham.'FOR THE PAST few years, one of the saddest sights on the fringes of Sneinton has been the former Plumptre Hospital almshouse in Plumptre Square, at the western end of Fisher Gate. Isolated nowadays in a wilderness of incessant traffic, it is certainly no longer a suitable place for elderly people to live. Nonetheless, the building merits something much better than its current state of neglect, and it must be hoped that an appropriate use is soon found for it.

Nottingham has lost many of its inner-city almshouse buildings since the Second World War, and is much the poorer without these attractive and harmonious features of its streets. To mention just a few; the Labray, Gellestrope, and Hanley Almshouses, forming a tight little bunch in Derby Road, Wollaton Street, and Hanley Street respectively, added much character to the urban landscape. Elsewhere the Bilby Almshouses in Cooper Street, off Alfred Street Central, and the Burton Almshouses in London Road, lent architectural interest to mundane areas of the city.

Regrettable though the disappearance of all these may have been, it was the demolition in 1956 of the important early eighteenth century Collin Almshouses in Friar Lane that caused a notable row, bringing down deserved opprobrium upon the heads of those responsible. 'A lovely group, one of the best almshouses of its date in England', was Nikolaus Pevsner's opinion in the Nottinghamshire volume of his 'Buildings of England' series. The revised edition of Pevsner could only include a terse note lamenting that the Collin Almshouses had been 'tragically demolished.' While it can never be argued that the Plumptre Hospital is of equal architectural rank, it is, dating as it does from the 1820s, the oldest surviving almshouse building remaining in Nottingham, and represents the earliest almshouse foundation active in the city. It is also a building of some charm and interest.

The origins of the hospital were these. John de Plumptre, four times mayor of Nottingham, and a merchant of the staple of Calais, trading mainly in wool, was granted a licence in 1392 by Richard II to found and endow a hospital or house of God for two chaplains and thirteen poor widows 'bent by old age and depressed by poverty.' It seems certain, however, that the hospital had already been in existence for a year or two before that date. An instrument of foundation dated July 1400 pinpointed its location, and attested to its religious foundation; in this document Plumptre stated that he had, to the honour of God and of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin, built a hospital at the end of the bridges of Nottingham. The Bridge End (sometimes Bridge Foot) was an open space at the town end of the Great Leen Bridge. This, the northern end of what is today London Road, had numerous arches which kept the roadway above the floodwaters of the Leen and its associated streams at rainy times. Between the twelfth and nineteenth centuries, in both of which its course was diverted, the River Leen flowed along the southern edge of Broad Marsh and Narrow Marsh; part of the present-day Canal Street was, of course, formerly known as Leen Side. As will be seen later in this short narrative, the name Plumptre Square is a comparatively modern innovation.

Like many founders of almshouses in the Middle Ages, John de Plumptre endowed a chantry for the two priests to celebrate masses daily for the welfare of the king, and of the hospital's founder and his wife during their lives, and for their souls after death. The priests were also to pray for the welfare of the county of Nottingham, and for the souls of all faithful dead persons, especially those who had given donations to the hospital. It was laid down that the chaplains support the poor women living in the hospital, and instruct them in the Catholic faith. They were also enjoined not to misappropriate the rents and income from the hospital charity. One of the chaplains was to be called the master, the other the second chaplain; they were to live at the hospital all the time, and receive 100 shillings a year from the rents of a number of properties owned by the charity in Nottingham. These included buildings in the Little Marsh, Barker Gate, and Fisher Gate. Serving a Nottingham which at the end of the fourteenth century had about 2,000 inhabitants, the Plumptre Hospital was one of about 750 such charities in England in the Middle Ages, many of them established by generous townspeople like John de Plumptre. It was, incidentally, not uncommon for almshouses to be established for thirteen inmates, representing the sum of Christ and his apostles.

In 1415 John de Plumptre made another instrument of foundation, in which the total of poor women living at the hospital was set at seven - three more centuries were to pass before their number rose to thirteen. He also left to the hospital his own house at the corner of Cuckstool Row (now the Poultry); this occupied the plot of land on which the Flying Horse was afterwards built. The right of patronage to the chaplaincy after his own death was given by Plumptre to the Prior of Lenton, the richest religious house in Nottinghamshire.

Little is known of the accommodation provided at the Plumptre Hospital before the Reformation, and the Dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s. The nineteenth century historian John Blackner was, however, scathing about the likely way in which the hospital had been conducted, and it seems probable that, as in many religious foundations, most of the income went on supporting the chaplains, and that as the widows admitted by John de Plumptre died off, few, if any others, were appointed in their places. Writing in the eighteenth century, one of the hospital's masters or guardians wrote: 'With reference to the first 130 years I find no manner of Remains concerning this Hospital.' It is known, however, that by the time of Henry VIII and Edward VI, it had declined to a sorry condition. Laws having been passed following the Dissolution enabling the Crown to seize all chantries, hospitals, free chapels, colleges, and the like, the commissioners appointed to carry out a survey in Nottinghamshire reported of the Plumptre Hospital that: 'Although the foundacion herof was to be an hospitall for the Relief of the Poore, yet a preist hath had the hole Revenue therof, and the poore then by nothing relieved.'

Following the commissioners' findings, the chantry at the Plumptre Hospital was abolished in 1548/49, and the hospital vested in the Crown. Its endowments remained undisturbed, however, and the most significant change was that the right of presentation passed to the Crown. From the reign of Elizabeth I the office of master, now a secular one, has been granted, with a few exceptions, to members of the Plumptre family. Since 1582 the only others to have held the office have been those appointed pending the coming of age of the next Plumptre.

It is difficult to imagine now just how sudden and dramatic an effect the Dissolution had on charitable foundations throughout the country; virtually no new almshouses were built for three decades, and great numbers of the poor who already lived in such places were made homeless by the suppression of many medieval hospitals. Those especially at risk were inmates of bede-houses, whose duty was to pray continually for the souls of the founders. All almshouses came under close examination, and in many cases religious foundations were confiscated from the Church, and suffered to remain in existence as secular charities run by their local town authorities.

Exactly what the first Plumptre Hospital looked like is not known. Drawings of its successor, however, appear in Thoroton’s 'Antiquities of Nottinghamshire', published in 1677, and Deering's 'Nottinghamia Vetus et Nova', 1751. One calls it a successor, but this building, rebuilt by Dr Huntingdon Plumptre in 1650, and still accommodating seven inmates, incorporated a considerable amount of the mediaeval structure, including the wall of its old chapel facing Fisher Gate.

In 1735 a legal dispute arose between the mayor and aidermen of Nottingham, and John Plumptre, the master, over the disposal of profits from the rents and properties belonging to the charity after all expenses had been paid. In response to arguments put forward by the town's representatives, John Plumptre stated that, like his father and grandfather, he had supported seven poor women in the hospital, and that nearly all the income of the foundation had gone in improving and repairing its buildings, and in erecting twelve new dwellings. He allowed the widows five shillings a month each, with an extra sixpence on New Year's Day, and a ton of coal yearly.

In the 1750s, with the repair of the old building, and the addition of new habitations, the number of poor widows accommodated in the Plumptre Hospital was at long last brought up to the thirteen originally intended by the founder. At this date the widows were receiving £1.2s.6d per month, and were, in addition to their New Year bonus and ton of coal, provided with a new gown annually. By now Nottingham had almost 11,000 inhabitants; there were fourteen almshouses to care for the poor and aged in the town, accommodating between them just over a hundred people.

At the end of the eighteenth century it was ordered that the master of the hospital be allowed to retain his £10 annual stipend, while paying £15 to an agent who would collect rents from properties owned by the charity, and attend to all repairs. The early nineteenth century brought the practice of appointing out-pensioners of the Plumptre Charity; as will be described later, there was to be controversy in Nottingham as to whether some of these were properly entitled to the help of the charity.

Returning to the Plumptre Hospital building as it existed after 1650, the engraving in Thoroton depicted a main front, facing west like that of the succeeding building. Its wings had attractive Dutch gables, and it has been suggested that the hospital was the first building in Nottingham to incorporate this architectural fashion. These gables were adorned by ball finials. Above the central entrance was a lozengeshaped stone enclosing the Plumptre arms, and a balustraded parapet topped the central part of the façade. Behind this, along the Fisher Gate frontage, was the buttressed wall which remained of the old chapel.

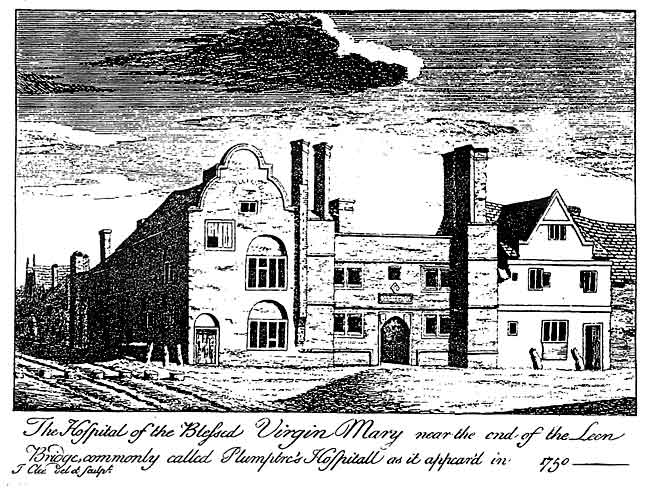

ENGRAVING OF THE HOSPITAL IN 1750, from Deering’s 'Nottinghamia Vetus et Nova'. Clearly, the building looked altogether more time-worn than in Thoroton's day.

ENGRAVING OF THE HOSPITAL IN 1750, from Deering’s 'Nottinghamia Vetus et Nova'. Clearly, the building looked altogether more time-worn than in Thoroton's day.By the time the drawing for Deering's history was carried out, the southern wing had become smaller, and had lost its Dutch gable for a humbler pointed one. The chimneys had been rebuilt, the balustraded parapet replaced by plain masonry, and altogether the place bore the signs of age and wear. The following six decades appear to have brought about the almost total dilapidation of the hospital. When Deering measured the building in the middle of the eighteenth century he stated that, judging by the old work, the west front must have originally been 74 feet across, and the engraving in his history suggests that a building of considerable size was still in existence then. However, John Blackner, who measured the hospital in 1814, claimed that it was by now a mere 27 feet along the west front. Blackner, Radical publican of the Rancliffe Arms in Sussex Street, quite close to the hospital, was by no means an unbiased chronicler, and some of his 'History of Nottingham' is extremely sketchy on historical fact. On the Nottingham of his own day he is, however, invariably lively and informative. His observations on the Plumptre Hospital, under the chapter heading 'Hospitals, almshouses, and other charities’, betray his prejudices. In a caustic remark previously alluded to, he says: 'Prior to the reformation, this institution, with much propriety, might have been classed under the head, chapels, but since the endowment has been better applied, than in maintaining two lazy priests to teach a few old women how to count their beads and mumble their pater-nosters, it comes properly under the present head. ’ Blackner also talked to two octagenarian occupants of the hospital, who shed tears of joy and gratitude when asked about their conditions, and were particularly appreciative of Francis Evans, steward of the charity. 'Mr Evans,' they said, 'is so good a gentleman that he never lets us ask twice for anything.' They also enjoined Blackner to 'be sure to give Mr Evans a good character.'

In 1812, a year or two before Blackner described the Plumptre Hospital, it had been mentioned in the Nottinghamshire volume of F.C. Laird's 'Beauties of England and Wales'. It seems likely that the writer of the latter had never visited the hospital, since he reported a structure unchanged from the one illustrated by Thoroton in 1677; 'Little of the first building is. we believe, now in existence, yet much of what remains is of considerable antiquity, and seems of Elizabeth's time, or a little before. It has a centre with balustrade on top, two wings or ends of semi-circular zigzag outline in the roof, and the windows of plain stone work.' Unless J. Clee, who drew and engraved the plate in Deering’s history, was totally inaccurate in his depiction, this account cannot be right, and, indeed, it suggests that Laird had written it up from what he had seen and read in Thoroton. This appears all the more probable in the light of the fact that John Throsby's revision of Thoroton, published in the 1790s, and easily accessible to Laird, still included the engraving of the hospital that had appeared in the original 1677 volume. It seems safe, therefore, to regard Laird's description of the building as second-hand and incorrect.

We are, however, leaping ahead of our tale, and before we reach the building of the next Plumptre Hospital on the site, something more should be said about the more important members of the Plumptre family. The home of the founder, John de Plumptre, was, as we already know, in what is now the Poultry, and he and his wife were buried in the nearby St Peter’s church, though most of the later Plumptres who lived in the town were buried in St Mary's. In 1504 Henry Plumptre bought land and property on the north side of St Mary’s church, and here the family mansion, Plumptre House, was built. This was improved in the middle of the seventeenth century by Dr Huntingdon Plumptre, who also rebuilt the Plumptre Hospital at the same time. He was a man prominent in several spheres of activity, and the object of much vituperative comment in Lucy Hutchinson’s life of her husband, Colonel John Hutchinson, who commanded Nottingham for Parliament during the Civil War. She stated that as a young man Huntingdon Plumptre 'was a doctor of physic, an inhabitant of Nottingham, who had learning, natural parts, and understanding enough to discern between natural civil righteousness and injustice; but he was a horrible atheist, and had such an intolerable pride that he brooked no superiors, and having some wit, took the boldness to exercise it in the abuse of all the gentlemen wherever he came.' Mrs Hutchinson clearly found it hard to forgive Plumptre for having been, although a leading Parliamentarian, a moderate man, and a less than fanatical supporter of the cause. Even more damning in her eyes must have been the fact that Huntingdon Plumptre had once struck her husband, and challenged him to a duel; this challenge, however, was not taken up by Hutchinson.

Thoroton wrote of Huntingdon Plumptre as 'being then eminent in his profession, and a person of great note, for wit and learning, as formerly he had been for Poetry when he printed his book of Epigrams and Batrachomyomachia...' , and recalled that he pulled down the old hospital building, increased the rents of the properties owned by the charity, and doubled the allowance to the poor. Huntingdon Plumptre's book was printed in 1629, and consisted of more than a hundred Latin epigrams addressed to his friends and acquaintances, (many of them, interestingly, later to be prominent Royalists during the Civil War,) together with his own Latin version of Homer's 'Batrachomyomachia' [Battle of the Frogs and Mice]. Plumptre, then, was clearly notable as a scholar and as a political figure, as well as being 'accounted the best physician in Nottingham.' by Gervase Holles. Writing in 1658 of Huntingdon Plumptre attending the Earl of Clare during his last illness, Holles, too, observed that Plumptre was 'a professed atheist.' This successful and apparently popular man (except with Mrs Hutchinson) died in 1660, aged 59, having put the hospital and the charity in good order.

Plumptre House was enlarged in the 1720s into a Palladian mansion, to the designs of Colen Campbell. Some indication of the standing of the Plumptre family may be gauged by the fact that this was. so far as is known, the first private house in Nottingham on which a nationally known architect worked. The last member of the family to live in this handsome Georgian house was John Plumptre, Member of Parliament for Nottingham, and one of the original trustees of Nottingham Blue Coat School, who moved away from the town upon his marriage. Some years before his death the house was divided into tenements, and the land attached was sold in 1796 and 1797. After periods in which it stood empty, or had various private occupants. Plumptre House became for a time a girls' boarding school: in 1851 fifteen girls were instructed there in English, French, and music by four teachers. Two years later, during the development of the Lace Market, the building was sold to Alderman Richard Birkin, who pulled it down. On part of the site he built lace warehouses, while the remainder was used to form the new thoroughfare named Broadway. The entrance archway to the former Birkin warehouse in Broadway still has a carved Plumptre family arms set into its wall; this was evidently moved from Plumptre House at the time of its demolition.

One minor member of the Plumptre family is mentioned here, not because he has any bearing on the story of the hospital, but because I simply cannot bear to leave him out. He was Henry Plumptre, who died in 1719, aged ten. The formidable accomplishments of this infant are vividly recalled in the inscription on his memorial tablet in St Mary's church. 'In these few and tender years he had to a great Degree made himself Master of the Jewish, Roman, and English History, the Heathen Mythology, and the French Tongue: and was not inconsiderably advanced in the Latin.'

The family is still commemorated locally by Plumptre Square and the nearby Plumptre Street, and rather less obviously in Pemberton Street, off Canal Street, where the charity owned some property. In 1788 John Plumptre married Charlotte Pemberton of Trumpington, near Cambridge. Their eldest son John Pemberton Plumptre was master of the hospital from 1818 to 1864, and their second son Charles Thomas Plumptre laid the first stone of the new hospital building in 1823. Family associations were also celebrated in the now-vanished Fredville Street, which lay between Carter Gate and Water Street, very close to the site of the present Trent bus garage. Fredville Street's final residents moved out just before the Great War, but its last houses were not demolished until about 1923. John Plumptre M.P., already mentioned as the last member of the family to live at Plumptre House, had in 1756 married Margaretta, daughter of Sir Brook Bridges, owner of the Fredville estate near Nonington in Kent, between Canterbury and Dover. Plumptre married in his forties, and though his first wife died within a couple of years, never again made his home in Nottingham. He and his successors resided at Fredville, of which he had become legal owner on his marriage, and that house with the faintly risible name remained the Plumptre seat until its demolition about 1939.

Reference has already been made to the Plumptre Charity’s out-pensioners. The first of these were twelve widows appointed in 1806 by the then master of the hospital, though this addition to the establishment of the charity seems not to have been sanctioned by law. In 1815 a further eighteen out-pensioners were provided for, and were approved by the legal authorities. In 1822 an Act of Parliament enabled the charity to sell three unproductive pieces of land: to raise money by mortgaging the residue of the estate: and to erect a new hospital on the site of the old. The Nottingham builder and surveyor William Stretton had already reported that the hospital and several other buildings owned by the charity were so old and decayed that anything less than complete rebuilding would be a waste of money. The hospital in particular was in a poor plight, having been repeatedly patched up since 1650, as we have seen. Street works had raised the level of the surrounding thoroughfares to some three or four feet above its basement floor, resulting in 'a very inconvenient and unwholesome habitation.' It was, concluded Stretton, 'absolutely necessary that the same should be entirely rebuilt.'

Nottingham, having doubled its population since the middle of the eighteenth century, was by the 1820s home to about 40,000 people. There were at this time still only fourteen almshouses here, so clearly further charity provision was sorely needed for this rapidly growing, and extremely cramped, town.

A select Biography and acknowledgements will appear with Part 2.

< Previous