< Previous

SIX HUNDRED YEARS OF THE PLUMPTRE HOSPITAL:

Pt. 2: Quite an ornament to that part of town

By Stephen Best

'QUITE AN ORNAMENT TO THAT PART OF THE TOWN .. . light, airy, and comfortable'.

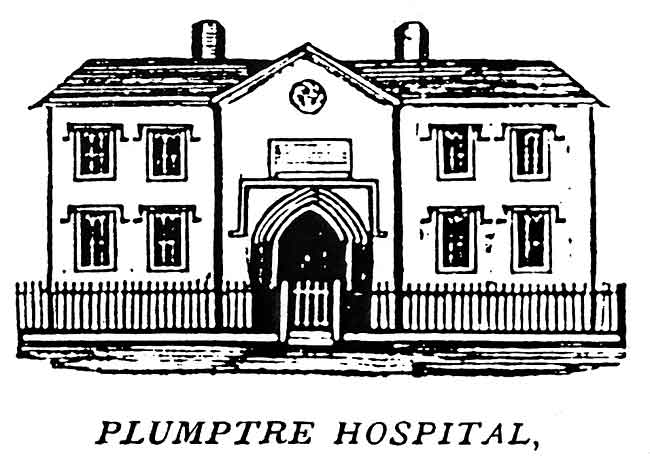

'QUITE AN ORNAMENT TO THAT PART OF THE TOWN .. . light, airy, and comfortable'.Edward Staveley’s new Plumptre Hospital of 1823, as depicted in the 'Stranger's Guide.'

(Part 1 of this article, in Sneinton Magazine no. 65, followed the fortunes of the the Plumptre Hospital through its first four centuries. In a sad plight by the middle of the sixteenth century, the almshouse was rebuilt in 1650; by 1820, however, it was clear that an entirely new building was sorely needed.)

FOLLOWING ACCEPTANCE OF the expert opinion on the state of the old hospital, demolition, and clearance of the site, quickly took place. All was ready in the summer of 1823 for the construction of the building's successor. The Nottingham newspapers printed lengthy accounts of the laying of the first stone of the new Plumptre Hospital on 1 August of that year. As already stated, the stone was laid by the Reverend Charles Thomas Plumptre of Claypole, just over the county boundary in Lincolnshire, who represented his father, John Plumptre of Fredville, master of the hospital. The mayor, Octavius Thomas Oldknow, a Nottingham draper, was in attendance, accompanied by Aldermen Wilson and Barber. Other notables at the ceremony included the Rev. Robert White Almond, rector of St Peter's, Nottingham: Henry Percy, the hospital steward: and Edward Staveley, surveyor to the Corporation of Nottingham, who was architect of the new building.

The Nottingham Journal remarked on the presence of 'a numerous assemblage of persons, amongst whom were observed several ladies and gentlemen of the first respectability.' The paper considered that: 'the gratification of the scene was not a little heightened by the presence of the venerable inmates of the late hospital.' Though not explicitly stated in the press, it is clear that arrangements had been made for the accommodation of these old ladies during the period of demolition and rebuilding of their homes.

The Mayor read out the words inscribed on a brass plate to be fixed on the foundation stone, and delivered what the Journal considered to be 'a concise, appropriate, and complimentary address.' Alderman Oldknow observed that they were to see the first stone laid; 'not of a magnificent mansion, not of a building erected for private convenience, but of a hospital for the reception of widows in their declining years.' He thought it most gratifying that this was being done by a direct descendant of the hospital's founder, and hoped that the Plumptre line would never die out. The mayor did, however, venture to comment on the fact that the family seat was now at Fredville. 'He could not suffer the present occasion to pass by, without expressing his regret, that the Town of Nottingham should be deprived of the immediate neighborship of an honorable house like this, which used to be so intimately connected with the Town, in times that are long since gone by. He hoped that connection might, at no great distance of time, be renewed...’

Not to be outdone in paying compliments to the Plumptre family, Alderman William Wilson followed, delivering himself of what the Journal called 'many flattering encomiums'. A cotton spinner at Ilkeston Road, New Radford, Wilson was brother-in- law to John and Richard Morley of Sneinton, founders of the famous hosiery firm of I. & R. Morley. He had been sheriff in 1798, and was eventually to be mayor four times. Appropriately enough for one attending this stone-laying ceremony, he was actually resident at Plumptre House for a while in the 1820s, after it had lain empty for some years. Alderman Wilson told his hearers that he took peculiar pleasure in thinking of a time when members of the family would again live in Nottingham, and ended his address by proposing 'that the square on the west front of the hospital, heretofore known by the name of Red Lion Square, should from this day be called Plumptre Square.'

Alderman John Houseman Barber, who lived only a few yards away, at the foot of Hollow Stone, surpassed both previous speakers in the grandiloquence of his tributes to the Plumptres. A grocer and tallow chandler, Barber had already been both sheriff and mayor of Nottingham. He was also to serve as mayor for two subsequent terms, one of them coinciding with the destruction of the castle. As a magistrate he was regarded as - 'a terror to evildoers', and in 1820 had survived an attempt on his life. It was assumed that the attacker was a man who had at some time been severely dealt with in court by Barber, but despite a reward of £515, a huge sum at the time, no one was ever arrested for the crime.

Alderman Barber reminded the assembly (if it needed reminding) that the Plumptre Hospital had been founded, 'not to support grandeur, or with any ostentatious motive, but to supply the wants of the widow, to relieve the distresses of the aged, and to comfort the heart of the female.' He went on to relate how the hospital had previously been rebuilt, and new tenements provided for occupants, 'but time, which wears all things out, and crumbles the proudest monuments of art, as well as the most useful erections of beneficence to dust, has brought the building to decay.'

Some of his later remarks were so fulsome that the master of the hospital, when he heard of them, might well have been grateful that he had been absent at the time. 'They now saw John Plumptre, Esq. appear before them in the person of his son, with a princely mind and liberal heart, with kindness in the act, and, might he not say, with a God-like intention, stepping forward to repair the injuries which time had done. '

The alderman recalled that, as a near neighbour of the hospital, he had known many of its residents, 'who, without such a comfortable asylum for the close of life, must have terminated their sorrows in a parish work-house.' He had no wish to disparage the workhouses, 'but in this hospital, the domestic comforts were superior; here the aged widow sat by her fire side, her wants were relieved by the liberal sum of more than 5s. per week, she had coals and a garment found her, as well as other comforts, and these were not trifles.' Mr Barber concluded by seconding the proposal that Red Lion Square be renamed Plumptre Square; after such a speech, he could hardly have done otherwise.

This seemingly impromptu announcement of the renaming of the square was only one of several instances in the nineteenth century of a name change being made, apparently on the hoof, by a member of the Corporation. For instance, in 1865 the widened Sheep Lane was opened by the mayor, who announced that henceforth it would be called Theatre Street. The townspeople, however, would have none of this, and the name Market Street was chosen instead. Then, in 1894, Alderman Pullman, on opening the remodelled Bath Street Recreation Ground, declared that it was to be named Victoria Park. There is no evidence to suggest that this matter had been discussed beforehand.

Nor was the name Red Lion Square hallowed by long usage, and the reader may well be wondering when it had first appeared. We know that John de Plumptre referred to the place in 1392 as the Bridge End, and for the next four centuries this name, or variants of it, such as Bridge Foot, were in general use. However, Red Lion Square was the address given by residents of the place in poll books between the years 1806 and 1820. By 1825, though, Alderman Wilson's proclamation had had its effect, and only one voter out of eight insisted that he lived in Red Lion Square, the other seven falling into line with Plumptre Square. It is likely, therefore, that Red Lion Square had enjoyed a currency of fewer than twenty years.

These worthy speeches delivered, the Rev. Charles Thomas Plumptre, 23 years old and newly-ordained, laid the stone, first placing beneath its position a complete series of the coinage of the reigning monarch, George IV. Mr Plumptre, according to the newspapers, showed keen awareness of the depth of respect shown to his family, past and present, and in return offered his sincere thanks for the honour conferred on the Plumptres in the renaming of the square. He also tendered his wishes for the welfare and prosperity of Nottingham.

As reported in the Nottingham Review, the brass inscription fixed to the foundation stone was worded as follows:- 'PLUMPTRE HOSPITAL. Originally founded and endowed for the support of a Master and a Priest, and 13 poor Widows, by John de Plumptre, in 1392. When almost decayed, it was in part renewed by a descendant of the Founder, Huntingdon Plumptre, Esquire, 1650. Besides other great Improvements, four new tenements were added by his grandson John Plumptre, Esquire, deceased, in 1751. His son, John Plumptre, Esquire, repaired the old buildings, and added two new tenements, thus completing the charitable design of the benevolent Founder, A.D. 1753. The first Stone of the New Hospital, erected by virtue of an Act of the 3d Geo IV, with the Coins inclosed, was laid by the Reverend Charles Thomas Plumptre, of Claypole in the County of Lincoln, Clerk, on behalf of his father, John Plumptre, of Fredville, in the County of Kent, Esquire, the Master or Guardian of the said Hospital, and a descendant of the Founder, on the first day of August, A.D. 1823. EDWARD STAVELEY, Architect.' The life of this brass plate must have been brief, as a slightly different inscription tablet was soon afterwards put up on the west front of the completed hospital building, together with another at the rear. This revised inscription on the façade was certainly in place by 1827. More will be said about it later.

Edward Staveley, architect of the new hospital, was an estimable servant of the town, serving from 1795 until his death in 1837 as surveyor to the Corporation of Nottingham. The first to receive a regular salary for this position, he was born in Leicestershire, into a well-known family of monumental masons and surveyors. The great water and gas engineer Thomas Hawksley was, as a young man, articled to Staveley in his Nottingham office. This was a notable pupil, since it is arguable that Hawksley did more than any other man to improve living conditions in nineteenthcentury Nottingham.

Another building of Edward Staveley’s which survives in central Nottingham, though much altered, is the former Baptist Chapel of 1815 in George Street, now the Co-op Arts Theatre. Perhaps his most abiding monuments, however, are the very fine maps of Nottingham which he executed between 1830 and 1831 with his assistant and successor as surveyor, Henry Moses Wood. Staveley died aged 69 on 10 April 1837, at his house in the Park, Nottingham, the Nottingham Review of that week observing that: 'This gentleman was highly respected, and filled the responsible position of surveyor and accountant to the corporation of Nottingham, for the long period of 40 years.'

After all the fine words spoken at the stone-laying, there appears to have been little public comment about the finished Plumptre Hospital building. The 1827 'Strangers’ Guide Through the Town of Nottingham', however, includes a charming little engraving of the hospital, with some approving remarks: '...Some land in the town, belonging to this hospital, was disposed of, and an entire new building was erected on the site of the old one... The present building, which was erected after a design by Edward Staveley, Esq., architect, is quite an ornament to that part of the town, and the apartments within are light, airy, and comfortable. It is substantially built of brick, in the ancient style, and covered with stucco, in imitation of stone, the whole being surrounded by a neat iron railing...'

The new hospital contained six single rooms for residents on the ground floor, and seven upstairs. The style adopted for the building by Staveley was, as the ’Strangers’ Guide’ suggested, a quietly attractive one. The square-headed perpendicular windows have minimal tracery at their heads, and are topped by prominent hood moulds. The main doorway has a four-centred arch, and over it is the resited and reworded inscription tablet, with the Plumptre arms above surrounded by the family motto 'Sufficit meruisse' ('To have deserved is enough') within a garter. The arms themselves consist of a chevron between two mullets and an annulet: two stars and a ring in lay parlance. The hospital front possesses a modest and rather unemphatic pediment.

The present inscription tablet, unlike the brass one placed on the foundation stone in 1823, does not mention the coins buried at that time. It also records that the first stone of the hospital was laid 'by the Rev. Charles Thomas Plumptre, Rector of Claypole...' A pedant might point out, however, that this latter statement is not strictly true; C.T. Plumptre was not instituted rector there until December 1823, and was therefore not yet holder of the living at the time of the ceremony in the preceding August. The original inscription, describing him simply as Clerk [in Holy Orders], was correct, and the tablet has thus innocently misinformed passers-by for the past 170 years or so. It is no doubt a trifling point, but one worth mentioning. Had the wording read '...later Rector of Claypole...', all might have been made clear to at least one pettifogging researcher in the late twentieth century.

Charles Thomas Plumptre’s rapid preferment to the incumbency before he was even ordained priest was surely linked to the fact that the living of Claypole was in the gift of the Plumptre family. A long succession of Plumptres were rectors of Claypole in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though by no means all of them lived in the parish. C.T. Plumptre followed his cousin Henry as rector, and was succeeded in turn at Claypole in 1842 by his younger brother, another Henry. In 1835 Charles Thomas Plumptre became linked with another prominent local family, when he married, as his second wife, Elizabeth Wright of Lenton.

The rear elevation of the hospital, facing the garden courtyard, bore (and I think still bears) a second inscription, reading as follows: PLUMPTRE HOSPITAL. Originally founded and endowed for the support of a Master, a Priest & 13 poor widows by John de Plumptre in 1392. When almost decayed it was in part renewed by a Descendant of the Founder, Huntingdon Plumptre Esq., in 1650. Besides other great improvements, Four New Tenements were added by his Grandson John Plumptre Esq., deceased in 1751. His son John Plumptre Esq. Repaired the old buildings and added two New Tenements thus completing the Charitable Design of the Benevolent Founder. A.D. 1753.' In his 'History of Nottingham' (1840), James Orange recorded that this inscription had been placed on the previous hospital building about 1753, in place of an earlier one in Latin which had become worn away. Orange, like the writer of the 'Strangers' Guide’, evidently approved of Staveley’s new hospital, describing it as 'the present elegant structure.'

Not long before the appearance of Orange's history, the report of the Charity Commissioners on Nottinghamshire was issued. They went into great detail about the allotment of places in the Plumptre Hospital, and the admission of out-pensioners to the charity. Briefly, their view was as follows. Though no instructions had ever been given about the poor widows to be selected for places in the hospital, it could be presumed that the founder had had in mind people living in or near Nottingham; inmates had in fact generally been chosen from this neighbourhood. Indeed, until lately, the advantages of residing in the hospital had been insufficient to attract applications from widows living at a distance from the town.

The out-pensioners, though, came into a different category. As already mentioned, John Plumptre had appointed the first twelve of these in 1806 without obtaining the approval of the Court, but the practice had received official sanction ten years later with an order increasing their number to thirty. It was acknowledged that the establishment of these out-pensioners had been made possible only by the increase in the charity's revenues.

In the absence of any contrary direction, Mr Plumptre believed himself free to admit out-pensioners from wherever he chose. In the late 1830s, 26 of these lived at or near Fredville in Kent, presumably old servants of the Plumptre estate there. Two others were in Tunbridge Wells, one in Dorset, and one at Claypole. The Commissioners regretted that no instructions had been obtained from the Court of Chancery by the master on the appointing of out-pensioners, in particular those who lived far away from Nottingham. They concluded that some legal consideration should now take place, to determine 'whether the county of Nottingham ought not to be entitled, rather than the county of Kent, to a principal share of the benefit of this branch of the charity.'

The Commissioners' report also included a register of the properties in Nottingham then owned by the Plumptre charity. No fewer than 75 were listed, including the Flying Horse public house in the Poultry: a grocer's shop next door to it: and the Punch Bowl and Blue Ball taverns in Peck Lane. There were also a number of houses in Narrow Marsh, Leen Side, Fisher Gate and Butcher Street.

The Corporation of Nottingham returned to the matter of out-pensioners in November 1840, stating their opinion that the money distributed to those not resident in Nottinghamshire was 'an appropriation of the Fund inconsistent with the original intention of the Founder.' The master, John Pemberton Plumptre, eventually suggested a compromise solution; that, while the first twelve out-pensioner places remain unrestricted, the remaining eighteen vacancies should be filled, as they occurred, from widows living in Nottingham and Nottinghamshire. This practice continued to attract rumbles of disapproval, White's Directory for 1844 commenting: 'Thirty out-pensioners receive each £10 per annum, but these are, we consider, improperly selected near the master's own residence in the county of Kent, for if it pleased him to remove from the seat of his ancestor, we see no right that can justify him in transplanting to a distant soil, one-half of that ancestor's ancient charity which was bequeathed to the poor of Nottingham.'

Nearly thirty years later the 'Tourist's Picturesque Guide to Nottingham' of 1871 complained, rather less accurately, that: 'Some dissatisfaction has at times been felt because the master has at times appointed to the almshouses decayed and aged labourers from his estate at Fredville, in Kent, it being generally thought that the benefits of the hospital were intended by the pious founder originally and solely for the inhabitants of the town of Nottingham.'

In the light of the above observations, the census returns for 1851 are of particular interest, providing, as they do, a detailed glimpse of the inmates of the hospital, with their ages and places of birth. The oldest of the thirteen widows resident at that date was 95, and the youngest 72. Eight of these were natives of Nottinghamshire, and three others came from Leicestershire or Derbyshire. The two remaining were born in Durham and Shropshire, but all had almost certainly lived in the Nottingham area for many years, since locally-born daughters or granddaughters were living with seven of the widows. It was a surprise to discover that the inmates were permitted to share their accommodation - one widow even had a lodger who was not related to her.

Forty years afterwards, as recorded in the 1891 census, there were still thirteen widows at the Plumptre Hospital, all born in Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, or Leicestershire. The eldest, 89 year-old Ellen Henson, came from Radbourne near Derby, while the two youngest, Hannah Turner and Ann Walker, were 74, and natives of Sawley and West Bridgford. This time, just a couple of the inmates had grand-daughters living with them on the night of the census.

We move now into the twentieth century. In 1927, and just over a hundred years old, the hospital building was enlarged by the addition of a new block on the south end of the main frontage, housing a chapel on the ground floor, with matron's accommodation above. Plans for this work were submitted in August 1926 by the civil engineers Elliott and Brown of Upper Parliament Street, Nottingham. The extension does not stand to quite the same height as the rest of the building, and the symmetry of the west front is disturbed; nevertheless a commendably tactful match was achieved, and it is very hard to detect the later hand in the work. Funded by the charity, the new chapel, furnished with some stained glass in its windows, was consecrated by the Bishop of Southwell on 29 May, with the master of the hospital, Henry Western Plumptre, present.

The Plumptre Hospital was now run in accordance with the provisions of an Act passed in 1919, following a plan for its management put forward by the Charity Commissioners. A supplemental order of 1930 had brought some changes, and the main clauses may be summarized as follows. In accordance with ancient custom, the hospital and endowments were to be managed by the master or guardian, who was to appoint a Church of England chaplain. The master could also appoint and pay a matron or nurse, providing accommodation for her in the hospital.

The almshouse residents were to be no fewer than thirteen poor women of good character, at least sixty years old, who were from ill-health or infirmity wholly or partly unable to care for themselves. The out- pensioners, to number at least forty, were to be similarly qualified. The charity was now available to widows or spinsters resident in Nottingham, Eastwood, or Nonington in Kent and its adjoining parishes; or to widows living anywhere in England. Nonington was, as previously stated, near the Plumptre estate at Fredville, while Eastwood was another place long associated with the Plumptres. Just as at Claypole, the family had held the living, and a succession of Plumptres had been rectors of Eastwood between 1819 and 1907. Residents of the almshouse were to be paid not less than five shillings, and not more than ten shillings a week, and could receive a ton of coal per annum, half-a-crown at New Year, and up to two pounds a year for clothing. The out-pensioners were to receive between five shillings and 12s. 6d. a week, as the master determined.

Permission was granted in 1930 for the number of out-pensioners to be increased to eighty; at the end of the Second World War, however, there were just sixty-four. Thirty of them lived in Nottingham, sixteen in Eastwood, and eighteen in Kent. The charity, despite having over the years sold some of its Nottingham house premises, at that date still owned property in Fisher Gate, Leen Side, and Pemberton Street.

A very significant addition to the hospital's accommodation was provided in 1959 when a block of twelve modern self- contained flats was put up in Canal Street, between its junctions with Cliff Road and Pemberton Street. Announcing in 1956 the decision to build these, the clerk to the charity told the Guardian Journal that the master now felt that the provision of out- pensions was no longer so important, as those living in their own homes could get help from other bodies. He therefore believed that the charity's resources could best be spent on providing more almshouse places, and the authorities had agreed.

It was reported in the Guardian Journal of 16 December 1959 that none of the residents in the existing hospital had expressed a wish to move into this new block. Its architect, John Howitt, replied to criticisms of the location of the new flats, on a busy main road, by pointing out that the Plumptre Hospital residents liked to feel they were still in the middle of the bustling city where they had spent their lives.

Commenting on the availability of the Plumptre charity to people from Kent, the newspaper reported that there were no occupants originating from that county in the old almshouses, or among those who had applied for one of the new flats.

The inscription plaque over the door of the new block, embellished by the Plumptre coat of arms*, records that these flats were erected during the mastership of John Huntingdon Plumptre. It seems most appropriate that the master responsible for their building bore the forename of one of his most distinguished ancestors, who also did much to improve the hospital's accommodation.

The 1927 chapel in the older building was remodelled in 1961 for the use of the twenty five elderly women residents of the two almshouses, but only three years later a new chapel was built in the rear garden of the old hospital. This was a small, plain building, with a pediment in basic neoGeorgian style. A bronze plaque beside the door read as follows: 'This Chapei was built in 1964 during the Mastership of John Huntingdon PLUMPTRE. It replaced a smaller Chapel which was added to the Hospital Building in 1927 during the Mastership of his Father Henry Western Plumptre, and which was too small for the needs of This Charity, after the new Almshouses had been completed.'

By the beginning of the 1990s the almshouse of 1823, now a Grade Two listed building, required a complete structural overhaul. It was judged that this was not financially viable, and so the family reluctantly determined on selling it. The agents told the Evening Post in October 1991 that they believed offers for the building would mainly be from those wishing to turn it into offices; and early in 1993 a different firm of agents suggested that solicitors or other professional people would eventually move in. Sadly, no one has yet done so, and the visitor to Plumptre Square today will find the building in a most distressing condition. Fly posters have been busy along its frontage, and many of the windows which are not boarded up are now smashed. The 1964 chapel has been demolished, and nature has returned with a vengeance to the back garden, where in summer rampant buddleias make it hard to realize that it is only a few years since the last residents moved out.

The 1927 chapel still retains bits of stained glass, though it must be doubtful whether these can survive neglect and vandalism for much longer. The hospital building lies islanded between Fisher Gate and Lower Parliament Street, with, in front of it, a short cul-de-sac stretch of road, officially part of Poplar Street. Now used, inevitably, as a car park, this could perhaps be turned into an attractive feature if the site is ever brought back to life. A planning application notice attached to the frontage of the hospital briefly excited feelings of hope, but a quick inspection revealed that a plan to convert the building into a nursery was put forward over a year before, and had evidently come to nothing.

This brief account has been written primarily with the intention of arousing awareness of the 1823 building, and concern for its future. It is, however, important to remember that the Plumptre Hospital Charity still carries on its good work. The current 'Directory of Grant-Making Trusts in Nottinghamshire’ gives its objects and policy as follows: 'Provision of almshouses and their maintenance for residents in Nottingham City. Also payment of pensions to poor widows and spinsters who are over 60 years of age. The income received from residents for their occupation of the Plumptre almshouse building and the income from investments support the main administrative expenses and outgoings in connection with this building. It also provides payment to a few pensioners.'

A recently published history of almshouses states that in 1988 Nottingham, with twenty-nine, comfortably possessed more surviving almshouse foundations than any other place in England apart from London. The Plumptre Hospital of 1392 was thus a pioneer in a long and proud tradition of charitable provision in the town. Long may it continue.

THE ABANDONED 1823 HOSPITAL BUILDING, late summer 1997. The additions of 1927 are on the right of the frontage. (Photograph: Stephen Best).

THE ABANDONED 1823 HOSPITAL BUILDING, late summer 1997. The additions of 1927 are on the right of the frontage. (Photograph: Stephen Best).SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY. Most of the printed and primary sources consulted during the preparation of this article are mentioned throughout the text, but an indispensable starting point has been J. Bramley’s 'Short History of the... Plumptre Hospital' (1946). I acknowledge my great debt to it. Three general books on almshouses have also been very useful, as follows: Brian Bailey, 'Almshouses' (1988): W.H. Godfrey, 'The English almshouse’ (1955): Brian Howson, 'Houses of noble poverty' (1993). Also recommended, though perhaps less readily accessible to the interested enquirer, are R.M. Clay, 'The medieval Hospitals of England' (1910): and Sidney Heath, 'Old English houses of alms' (1909).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: My thanks go to a number of people. The staff of both Nottinghamshire Archives Office and Nottingham Local Studies Library have given every assistance. The Rev. George Munn, rector of Claypole, and Mrs Michelle Barnes of Lincolnshire Archives, have kindly answered my queries about the Rev. C.T. Plumptre. Ken Brand has once again patiently allowed me to bounce ideas off him, and David Bradbury has carried out a valuable recent photographic survey of the building. Lastly, my wife Sue has, as ever, been my most searching literary critic and editor.

* The Plumptre arms displayed here are impaled with, I think, those of the Methuen family, three wolves' heads. In 1818 John Pemberton Plumptre married Catharine Matilda Methuen, daughter of Paul Methuen of Corsham Court, Wiltshire, and sister of the 1st Lord Methuen

< Previous