< Previous

SNEINTON’S HOSIERY DYNASTY:

The Morleys of I & R Morley:

Part 1: The workmen's friends

By Stephen Best

John Morley (1768-1848): The 'I' of I &R Morley.

John Morley (1768-1848): The 'I' of I &R Morley.A YEAR OR TWO AGO, the Turf Tavern in Parliament Street was renamed Samuel Morley’s. A number of protesting voices were promptly raised, including one in Sneinton Magazine.1 Now that the pub has happily regained its original name it is appropriate to remind ourselves of three things. Why is Samuel Morley of interest to Sneinton: why should it have occurred to anyone to name this particular pub after him: and why was it so unseemly that his name be given to licensed premises?

Samuel Morley was not born in Sneinton, yet his family was inextricably linked with the place. He provided many local people with their livelihood, and did immense good for countless others in Nottingham and elsewhere. His father, uncle, cousin, and son all played parts in the life of Sneinton, and he was offered, and declined, a peerage. He may be said to have suffered two major catastrophes in Nottingham; the first when at the height of his career, and the second more than forty years after his death.

The Morley family were for generations residents of Sneinton Manor House, tenants of the lords of the manor, the Pierreponts, who in the late eighteenth century became the Earls Manvers. In the 1760s an earlier Samuel Morley was a yeoman farmer, cultivating land around the Manor House, while at the same time interested in the growing trade of hosiery manufacture. This Samuel's son John was born at the manor house in 1768, followed seven years later by his brother Richard. Samuel Morley died in 1776, and was buried in the family plot on the south side of Sneinton churchyard. The brothers were brought up to follow their father in a combination of activities less unusual then than it would be today. While still young men, however, they realised that agriculture was not going to be their principal activity, and towards the end of the century formally established a hosiery firm.

As was not uncommon at the time, John and Richard Morley adopted a company style which did not distinguish between the printed capitals I and J, and their concern was accordingly called, not J. & R., but I. & R. Morley. The brothers had influential connections among Nottingham's ruling classes, including Wrights the bankers. Not only that, but their sister was married to the prominent cotton-spinner Alderman William Wilson, and they were on good terms with other members of the Corporation. Their financial standing was in consequence quite secure, with credit readily extended to them.

In the late 1790s they resolved that John Morley should go to London, and establish a warehouse there for the sale of goods made under Richard's superintendency in Nottingham and its surrounding villages. The first Morley warehouse in Nottingham was in Greyhound Yard, but within a couple of decades the firm had moved to Fletcher Gate, in time taking over almost the whole of the east side of that street. Here was their office, and storage and distribution centre for stockings produced on hand- frames in the homes of their cottage workers, and brought to the warehouse by middlemen, usually called bag hosiers.

The early years of I. & R. Morley coincided with the Napoleonic Wars, which brought an economic downturn which caused grave difficulties for the hosiery trade. Further problems followed with violent Luddite protests against the replacement of hand-worked stocking frames by mechanical ones, which could produce goods twelve times more quickly. Richard Morley sympathized with the fears of his out- workers, retaining the old frames after many other employers had scrapped theirs. From the start Morley's insisted that they would produce hosiery of only the finest quality, and demanded high standards from their out-workers. The Morley family were, by the criteria of the time, remarkably enlightened employers. They paid the best wages by the miserable standards of the time, did their best to ensure regular employment for their people, and waived rents when knitting frames stood idle.

Richard Morley continued to live at Sneinton Manor House, and in addition to running I. & R. Morley in Nottingham became a prominent member of the Corporation. Elected mayor in 1836 and 1841, he was an alderman and magistrate. A Poor Law guardian for the Radford Union which included Sneinton, he was involved in the setting up of the Mechanics' Institution, of which he was an early life member. From old Puritan stock, he was, like all the Morleys in this narrative, a devoted Congregationalist, being a deacon at Castle Gate Chapel. Although a Nonconformist, Richard Morley kept up the family connection with Sneinton parish church, and frequently attended services there, occupying a seat in the Morley pew, (perhaps more accurately the Manor pew.) ' Of his five sons, three took an active part in the business.

John, meanwhile, put the London end of the firm on its feet, in a modest way at first, living above the warehouse in the City of London. Thanks to his hard work and acumen the London sales of their Nottingham products grew enormously, and John Morley acquired a pleasant house at Homerton in North London, later moving to a grander one in Hackney; both of these places were then agreeably rural. He also grew increasingly prominent in Congregationalist circles in London. The little warehouse in Russia Row, off Milk Street, was soon found insufficient for the firm's needs, and I. & R. Morley took new premises elsewhere in the City, in Wood Street. There they gradually acquired building after building, until Morley's quite dominated the street.

Back in Sneinton, the agricultural interests of the family did not die out immediately, and a contributor to the Nottinghamshire Guardian at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries recalled harvest home at Sneinton at the time of his boyhood. This old gentleman stated that as the last load of corn was brought in, the workers sang or shouted the rhyme:

'Mr Morley's got his corn.

Well sheared and well shorn;

Never turned over, nor yet set fast;

The harvest load's come home at last.'

He further recalled that, when the last load of corn arrived, Mr Morley would give each boy sixpence. A Mrs Dunn, born in Barker Gate, had previously described how, when she was a girl, Barker Gate 'was then almost country. and we could see the Sneinton corn fields from our door, and hear them shout the harvest home. There were only two houses in the street below us, and a few thatched cottages.' The Sneinton farmers generally took their corn to Nottingham Market Place, though by the very early 1800s - the period remembered by Mrs Dunn - it is likely that selling there was done from samples rather than from bulk.

John Morley died in London in 1848, seven years before his brother Richard. Like Richard, John had three sons in the family firm, the youngest and most important being Samuel, the central figure in this story. Born at Homerton in 1809, the sixteen-year-old Samuel had begun work in Morley's London counting-house, preceded in the business by his brother John. Another elder brother, William, joined the firm later. Though they were valuable assets to I. & R. Morley, these two could not compare in stature with Samuel. His administrative skills were described in Morley's centenary history as amounting to 'commercial genius,' which, allied to his energy, capacity for work, and profound Christian convictions, were crucial in the company's future success. In 1832 Samuel came to Nottingham for a short while to manage a department engaged in the making of flannel underwear, the firm's first venture beyond socks and stockings. His father retired in 1840 to devote himself to charitable and Christian causes, so Samuel Morley, then just over thirty, became virtual chief of the London end of the concern. He married in 1841, and, as will shortly be seen, began a notable enlargement of the business.

RICHARD MORLEY (1775-1885): The 'R' of I & R Morley.

RICHARD MORLEY (1775-1885): The 'R' of I & R Morley.Richard Morley died at home in Sneinton in August 1855, having attained the age of eighty, as John did before him. During his final years he had watched the family concern based in Fletcher Gate grow and prosper even more strongly under the direction of his son Arthur. The Nottingham Review of 7 September 1855 reported Richard Morley's death in affecting terms: 'The deceased was one of the highly respectable firm of J. & R. Morley, hosiers, Gresham Street, London, and Fletcher Gate, Nottingham, and was considered in the trade as the workman's friend... To the poor of Snenton especially, his death will be a great loss. In every relation in life, he was valued and esteemed, and his family and friends will bear his name in affectionate remembrance.' It will be noticed that the paper did not conform to the convention of referring to the firm as I. & R. Morley.

A funeral discourse on Richard Morley was preached at Castle Gate on 9 September, by the Rev. Samuel McAll. He described Morley as: 'One who was eminently characterized by the domestic and social virtues; one who was a pattern as a husband, a father, and a friend. ' As a businessman Richard Morley had 'acquired a name for honour and integrity,' while as an em ployer he 'held high rank amongst those.. .who in their treatment of the operative classes are considerate as well as just... In him the afflicted and the destitute have lost a sincere friend.'

Handsome as these tributes were, they were equalled by later press coverage of the death of Richard Morley’s son Arthur. Having succeeded his father as head of the company in Nottingham, Arthur died very suddenly in his prime in January 1860. 'All who were aware, and who in this neighbourhood, despite his want of ostentation, was not, of Mr Morley's elevation of character, and truly Christian liberality of heart, will understand how general a shock was felt in Nottingham when it was reported on Sunday that he had died suddenly while on a railway journey.'

Travelling alone, Arthur Morley had been on the way to visit his clergyman brother- in-law in Poplar, London. This was 1860, remember, and the Midland main line from Bedford into St Pancras was not yet built.

Since 1858 it had been possible to travel from Nottingham via Bedford to Kings Cross, but it is clear that Morley used the old route, by the Midland Railway to Rugby, and thence up the London & North Western to London. There he had alighted at what the Review called 'Camden Town Junction' in order to connect with a North London Railway train to Stepney, where he would have had to change for Poplar. This junction was in fact Hampstead Road, soon afterwards renamed Chalk Farm to correspond with the adjacent LNW station.

These two stations lay alongside one another, connected by a lengthy covered footbridge spanning several lines of rail. Morley accordingly walked the hundred yards or so to the NLR, being obliged, as the paper put it, 'to traverse a long gallery'. He had chatted pleasantly with the porter carrying his luggage. In the North London booking office, however, he staggered, and fell into the porter’s arms with such force that both went down on the floor. Pronounced dead on the spot, he had, it transpired, succumbed to heart disease. A telegraphic message having been sent to Nottingham, 'The intelligence spread with the peculiar rapidity of disastrous news, and it is not too much to say, that a general gloom over the whole town was the result.' A bachelor, Morley was only 48.

The Nottingham Review considered that: 'The name of Mr Arthur Morley will long be remembered as that of a good Christian, a kind friend, a just merchant, a benevolent patron of the poor, a Liberal politician, and a constant and devoted Nonconformist.'

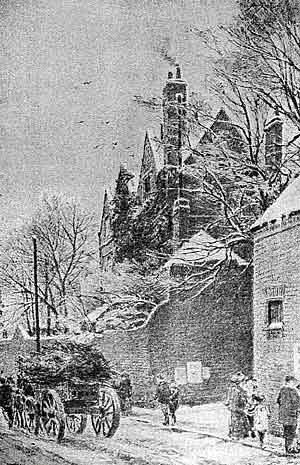

SNEINTON MANOR HOUSE, birthplace of John, Richard and Arthur Morley. This drawing by T W Hammond dates from a few years before its demolition in 1894.

SNEINTON MANOR HOUSE, birthplace of John, Richard and Arthur Morley. This drawing by T W Hammond dates from a few years before its demolition in 1894.Born at Sneinton Manor House, Arthur Morley had, as mentioned, been for some time in sole charge of I. & R. Morley's Nottingham concern. 'All his business dealings,' said the Review, 'were marked by the same uprightness and purpose which characterised Mr Morley in all his other transactions... his residence at Snenton was open to public men, either residents in Nottingham or visitors, of all professions and denominations; and very frequently his domestic circle was honoured by the presence of men of the highest eminence in their various walks.' Though accustomed to keeping such distinguished company, Arthur Morley was always anxious for the welfare of his workpeople, and exemplified the ideal caring employer of his time. 'Towards those below him, either household servants or business employees, he was always most kind and affable.'

Elsewhere in Nottingham he was a trustee and vice-president of the Mechanics' Institution, to which he was a generous benefactor, and took a leading part in the establishment of Young Men's Improvement Societies. Like his father, Arthur was a steadfast Congregationalist, but never a sectarian bigot. So he was often associated with people of other denominations in charitable and educational work. A member of the Castle Gate Chapel congregation, he became a deacon there shortly before his death. During the 1850s Morley was a prime mover in founding the Albion Chapel in Sneinton, and provided most of the financial backing for the Albion Schools.

Arthur Morley's funeral took place at Sneinton church on 17 January 1860. 'Some time before the hour appointed... crowds of people began to assemble in the church yard, and in the road leading from the residence of the deceased, and the mournful expression visible on almost every countenance evinced that some motive higher than mere curiosity had drawn them together. In the grounds leading to the house a number of ministers of the town and neighbourhood and of gentlemen with whom Mr Morley had in life been associated, were assembled to testify their respect.'

THE MEMORIAL in the south-east corner of Sneinton churchyard, believed by the author to commemorate Richard or Arthur Morley. Photo: Stephen Best.

THE MEMORIAL in the south-east corner of Sneinton churchyard, believed by the author to commemorate Richard or Arthur Morley. Photo: Stephen Best.The members of the cortege reflected all aspects of Arthur Morley's life. His coffin was flanked by leading Nottingham citizens, and carried by men who worked at Morley’s. They were followed by relatives, among them his cousin Samuel, for whose business life Arthur's death would spell enormous change. Six of the Morley household servants walked behind the family. A deputation from the Mechanics' Institution came next, and the procession ended with fifty-one warehousemen in Morley's employ, then ministers and friends. It was estimated that at least lour thousand people witnessed the funeral.

The vicar of Sneinton, the Rev. W.H. Wyatt, read the burial service before Arthur Morley was buried in the family vault. 'Although a strong detachment of the county and town police forces were in . attendance, their was little need of their services. The most perfect order was maintained throughout. A more convincing proof of the deep respect in which he was held by all classes of the community could not have been afforded.'

The interment poses a minor puzzle. The Nottingham Review states that the Morley vault was in the south-west portion of the churchyard, but it cannot ever accurately have been so described: one concludes that the reporter meant to say south-east, but got his bearings wrong. Writing in about 1912, Robert Mellors2 is clear that Arthur Morley 'was interred in the family tomb in Sneinton Churchyard, near to the Manor Street corner.' At the time Mellors wrote this, an inscription no doubt still survived on the memorial, and one is inclined to believe his version. It is probable that the monument concerned is the rather tall chest tomb with Gothic revival tracery, in the south-east corner of Sneinton churchyard, closest to the corner of Manor Street and St Stephen's Road, and some twenty yards from the earlier Morley gravestones. Stylistically it fits the date of burial of either Richard or Arthur Morley, and the carved name of J.E. Hall on the memorial supports this conjecture.3

The monument does indeed suggest that it commemorates someone of substance. The Morleys could easily have afforded an even grander memorial, but, as we have heard, the family was not given to displays of opulence or self-importance. Arthur Morley’s death brought to an end the long association of the family with Sneinton Manor House.

We return now to Samuel Morley. During the 1840s he had bought more property in Wood Street, London, and rebuilt on a huge scale the I. & R. Morley warehouse and offices at the corner of Wood Street and Gresham Street. Some could not believe that such enormous premises would ever be justified, but he was proved right and, vast as they were, the Wood Street buildings eventually exceeded their capacity. In 1855 the retirement of his brother John left Samuel Morley as sole head of the London end of the firm, which continued to produce only the very best quality goods, and by 1860 had some 3,700 framework-knitters working for it.

Morley’s had not changed their view that factory products were of lesser quality than that made on hand-frames, and went to great lengths to protect the standard of their goods. The work sent in to Fletcher Gate at Nottingham was inspected there by the manager, who demanded perfection, and the out-workers were in trouble if they had failed to attain it. Though Fletcher Gate was still the hub of the business here, further dramatic expansion was about to take place. On the death of Arthur in 1860 , Samuel became lone managing partner of the entire Morley empire. Possessing prodigious energy, he not only presided over a growing and massively profitable company, but continued his intense involvement in public life. To fill the position in Nottingham previously occupied by Arthur Morley, Samuel Morley appointed Thomas Hill as manager.

Hitherto Morley's had been organised around the premises where the firm contacted their middlemen who brought in goods made by out-workers. From now on, however, factories were to assume a greater importance. In 1856 Morley's had employed 2,700 out-workers in and around Nottingham, but Samuel steadily moved the company in the direction of factory manufacture on powered machines, now capable of producing work of a quality to rival the hand-frame. In 1866 Cropper's Factory in Manvers Street, at the corner of Newark Street, was purchased, and £27,000 spent in equipping it. The choice of this location was influenced by the long- established hosiery making trade in Sneinton, with plenty of skilled labour available within a few streets of the premises. The earliest years of the Manvers Street factory were very unlucky, seeing two serious fires. The first, in March 1872, was destructive enough, causing about £10,000 worth of damage. This, however, was made to appear insignificant two years later, when in August 1874 Morley's was the scene of the costliest blaze yet experienced in Nottingham. This time destruction was almost total, and the damage amounted to some £100,000. Although it had been under-insured, the factory was quickly rebuilt and extended. It resumed production in 1875, and eventually employed five hundred people.4

During the last fourteen years of Samuel’s life, five more factories were opened in the Midlands and London. In 1874 one was erected at Heanor, for dyeing and finishing goods from the Manvers Street factory. This was quickly followed by another at Daybrook, later greatly enlarged. In 1879 I. &. R. Morley established a further presence in Sneinton, with the acquisition of a factory in Handel Street, which gave work to a further 350 people. The 1880s saw new factories in Leicester; and, just after Samuel Morley's death, also at Sutton-in-Ashfield and Loughborough. A rose-tinted passage in the firm’s centenary history later asserted that the Sutton factory was 'situated in a most delightful spot,' where employees worked 'amidst these romantic suroundings. ’

Morley's factories were accounted the best in the North Midlands. They were clean, airy, and light, and relations between management and workers were excellent, based on mutual respect. Pay was higher than average, as befitted a firm which had from its beginnings always shunned the feared and hated truck system, under which workers had been paid in kind. Morley’s were also pioneers in providing pensions for many of long-serving knitters. During Samuel's time in command Morley’s diversified greatly, turning out gloves, nightdresses and underwear, and corsets. Between 1859 and 1871 the value of I. &. R. Morley's sales doubled from £1 million to £2 million.

Thomas Hill, who, as already mentioned, had taken charge in Nottingham in 1860, followed the Morley tradition of benevolent labour relations, and was in due time made a junior partner in I. & R. Morley’s. Born in Nottingham in 1822, Hill had married a young lady with the felicitious name of Miss Hose. He was highly respected, not only within the hosiery industry, but throughout the wider life of Nottingham. A member of the General Hospital Committee, and chairman of the Midland Counties District Bank, Thomas Hill was for a time a town councillor, and served as a magistrate for many years. A resident of The Park, he died in 1909.

This article is not intended to be a detailed history of the firm, and a brief summary must suffice to cover later years. I. & R. Morley took over several firms which had been rivals in the industry, and by 1900 had ten establishments, where over 4,600 people worked. In addition thousands of outdoor hands earned a living from Morley's by doing work at home for these various factories. Morley's dedication to their existing high standards resulted in the continued employment of nearly 4,000 framework knitters, actually more than they had been using when Samuel Morley assumed total control. This represented a high proportion of all the framework knitters still at work in the Midlands. I. & R. Morley were the chief manufacturer in the hosiery trade, and continued to be so until after the Second World War.

Family-owned, and not becoming a public company until the 1930s, Morley's was run on conservative lines. Its chairman took a leading part in an association formed to compel retailers to deal through trade warehouses, rather than directly with manufacturers; this, however, ran against current trends, and proved ultimately unsuccesful. During the War part of Morley's London premises was destroyed in air raids, and in May 1941 the Fletcher Gate building was severely damaged in Nottingham's worst raid. In spite of these setbacks, I. & R. Morley still had the biggest capital in the hosiery industry in 1950 - £1.6 million. Their traditional outlook, though, was ill-suited to the postwar age, to such an extent that in December 1967 The Times remarked that the firm was: 'having trouble in dragging itself into the twentieth century. Its products are of sterling quality, but not necessarily calculated to appeal to the mass modern market.' Morley's was therefore in no condition to withstand an acquisition bid by Courtaulds, and was taken over by that company early in 1968.

We have, however, run far ahead of our story, and must go back to the public, as opposed to the industrial, activities of Samuel Morley, whom we left in vigorous middle age, at the height of his powers. His interests were wide-ranging, and included the chairmanship of a committee formed to promote the return to Parliament of dissenter MPs. He also wanted to make Civil Service employment available to a wider section of society, and to ensure that promotion in the service was through merit, rather than family connections. Morley accordingly set up an association to advance these aspirations, but unhappily little came of them. He also became treasurer of the Home Missionary Society, and at about the same time, in the late 1850s, deeply involved in the temperance movement, with the result that he embraced total abstention for the remaining 29 years of his life.

Richard Cobden, the Liberal politician and 'Apostle of Free Trade,' suggested that Samuel Morley stand for Parliament, but he waited for some eight years before he took this step. Even then, he was reluctant to be nominated as a candidate for Nottingham in 1865. It was, of course, realized by his supporters here that Morley's influence as a substantial employer in the town was a very significant factor in his likely election to Parliament. In the event his decision to stand was to prove disastrous, as the election campaign descended into lawlessness and violence.

On 26 June the two Liberal candidates, Charles Paget of Ruddington and Samuel Morley, were due to address their supporters at an open-air mass meeting in the Great Market Place. Employees of Morley’s arrived by rail at teatime from Mansfield and elsewhere in the county, only to encounter a mob at the station: 'When commenced a scene of stone throwing as had not occurred in the good old town of Nottingham for many years.' The stonethrowers were the notorious Nottingham Lambs, gangs of street hooligans who would do anyone's dirty work for the price of a few pints.

Despite being assailed by further showers of stones, Morley's adherents managed to reach their platform in the Market Place, but were at length driven off by further volleys of missiles. Once left unattended, the platform was set alight, and blazed away fiercely. Done with arson, the rabble turned their attention to 'the windows of obnoxious parties,' including James Sweet's bookshop in Stoney Street, the Nottingham Daily Express offices in Victoria Street, and Paget and Morley's committee-rooms in Wheeler Gate. The disorder was finally put down late that evening, but not before some fifty people, including police, had been badly hurt. Samuel Morley had to stay hidden in his hotel because of the threatening crowd, while his supporter A.J. Mundella felt the need to set a guard over his own house.

The poll took place on 12 July, and more unruly behaviour characterized the day. High excitement gripped the town, until the Great Market Place was jammed with people at 4 o'clock, agog to hear who had won. It was soon announced that Samuel Morley and Sir Robert Clifton were the successful candidates; Morley had beaten Clifton by. only 47 votes, while Clifton was just 25 votes ahead of Charles Paget, the higher-polling of the losers.

Samuel Morley made his maiden speech in March 1866 on the Church Rates Abolition Bill, yet another of his great concerns. He was, however, already labouring under the shadow of a petition to unseat both him and Sir Robert Clifton. It was alleged that Clifton and his agents were guilty of undue influence at the election, by offering electors excessive travelling expenses to vote for Sir Robert. No charge of personal corruption was ever levelled at Samuel Morley, but it was stated that 'excessive numbers of persons were employed in behalf of Messrs. Paget & Morley as messengers, canvassers, and protectors from violence, and that in three wards alone out of seven nearly two hundred voters were so employed and received from their agent sums varying in amount from 15s to £4.10s.

Both members were unseated, Morley mortified to be tainted by allegations of bribery and corruption. We live in an age familiar with sleaze, and it is perhaps not easy to imagine a politician quite above such behaviour. Nonetheless it seems clear that Samuel Morley, at best a reluctant entrant to national politics, can have had no notion of what was being done on his behalf. There is, however, no doubt that the agents of both sides hired hundreds of men who, though nominally messengers and the like, were nothing more than an intimidatory mob.

Sir Robert Clifton was a personality in complete contrast to the upright Samuel Morley.5 As far as he had any party political leanings, Clifton was really a Liberal, but had represented Nottingham as an Independent since 1861. Having, however, voted with the Tories against the Liberals on a couple of controversial issues, he had again stood as an Independent in 1865. A feckless gambler and racehorse owner, he was an unreliable entrepreneur, crippled by debt. His breezy personality, though, appealed to the working man, who liked his passion for racing and the way he defended the right of the worker to enjoy a drink whenever he wished. Unlike Morley, Sir Robert almost certainly knew of, and approved, the employment of hooligans on his behalf.

The speedy upshot of all these indecorous goings-on was a by-election in May 1866, at which two Liberals were returned. Samuel Morley's personal reputation remained unscathed by events, and the Nottingham Liberals offered to support him at the next general election; Morley, however, declined. He became involved with the Liberal press, and a principal proprietor of the Daily News. To make the paper more accessible to the less well-off, he ordered that its price be reduced to a penny. The general esteem in which he continued to be held led him to stand for Parliament at a Bristol by-election in April 1868. He lost by just 196 votes, but, in a bizarre reversal of Morley's Nottingham experiences, his victorious opponent was shortly afterwards unseated on petition. Samuel Morley eventually became an MP for Bristol at the General Election in November, winning by 'a triumphant majority.'

Morley remained MP for Bristol until he retired in 1885. He was always an unswervingly loyal Gladstone man, hardly ever questioning any of his great leader's opinions or policies. He gave generously to the election funds of Liberal candidates, and especially provided financial help for Labour Representation League candidates. The League was an organisation sponsored by trade unions for securing the election of working men to Parliament as Liberals. Morley was deeply interested in education, and, after long opposing a state system of teaching, announced himself a supporter of it. Always vigilant over the rights and interests of dissenters, he advocated Bible teaching in board-schools, subject to a teachers’ conscience clause. For six years, as a member of London School Board, he favoured Biblical unsectarian teaching. He supported new colleges, and took particular interest in providing opportunities for those who, by reason of religion or class, had previously been shut out; Morley College in London was named after him. On the consulting committee of the Agricultural Labourers' Union, Samuel Morley was also for some years a director of the Artisans', Labourers', and General Dwellings Company.

There were, however, limits to Samuel Morley's tolerance and breadth of interests, and his conscience would not allow him to back the admission to Parliament of the atheist Charles Bradlaugh. Another quirk, according to his biographer Edwin Hodder, was that when taking on poor lads as apprentices in his firm: 'Mr Morley would not, for the sake of the others, allow a Roman Catholic to come amongst them lest he should - as duty bound - seek to propagate the tenets of his Church.' The inflexible side of his nature also showed in private life, where he disapproved of not only drinking, but also of smoking and dancing. For all his genuine kindness and goodness, Samuel Morley must sometimes have appeared irritable and domineering. He chose to believe that his own family was like a republic in its freedom, though his children later commented that this was a republic 'with a dictator at its head.'

Much of his vigour in later years was channelled in support of the Blue Ribbon temperance movement. So strongly did Morley feel about the evils of strong drink, that he considered voluntary efforts to gain its abolition were not enough, and that legal means would be necessary to curb its effects. He therefore played a prominent part in supporting bills to restrict public house opening hours, and to prohibit the payment of wages on pub premises. This last practice was the cause of enormous distress to poor families, men sometimes drinking away a substantial part of their weekly pay before leaving the public house to go home to wives and children.

Towards the end of his life Morley made a significant gesture that enriched, not only Nottingham, but, indirectly, communities all over the country. In June 1881 the new buildings in Shakespeare Street and Sherwood Street, housing the University College, Central Library, and Natural History Museum, were opened by Prince Leopold. This, of course, was a public provision after Samuel Morley’s heart, and 'anxious to have had some little share in this most promising enterprise,' he had something further to propose. On 20 August he wrote to the Mayor, as follows:

'I believe the Library is open only to those who are 15 years of age, but I should like to reach children who are far younger than that, and who have begun to take - as many do - an interest in books and reading.

Everywhere in our large towns the working classes are deluged and poisoned with cheap, noxious fiction of the most objectionable kind. I should be thankful to help do something to counteract this mischievous influence, and if young people are to have fictitious literature, and I see no reason why they should not. to do something to ensure that all events, it shall be as pure and wholesome as we can provide for them. I gladly offer £500 as a commencement of a library for children, say from the age of seven or eight to fifteen. Every point of detail I would cheerfully leave to the decision of those who have proved, by their management of the Free Library, their thorough competency to take the management of this new effort if it should be agreed to.'

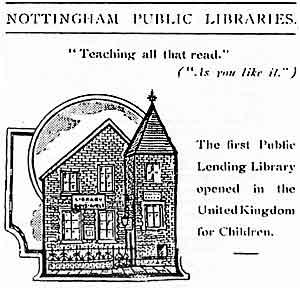

THE CHILDREN’S LIBRARY in Shakespeare Street, opened in 1883 with a donation from Samuel Morley.

THE CHILDREN’S LIBRARY in Shakespeare Street, opened in 1883 with a donation from Samuel Morley.Here, one suggests, is the essential Samuel Morley, an enlightened man of his times, though undoubtedly, by today's standards, very strait-laced. It would be wrong, though, to characterize him simply as one of the stony-faced Gradgrinds whose Victorian values were so warmly espoused again a decade or more ago. Although he once said that: 'Life is really a continued competitive examination,' Morley was not scornful of those less able or fortunate than himself who failed to pass that examination. Anyone tempted to regard him as a reactionary fuddy-duddy might bear in mind that Samuel Morley welcomed the creation of the TUC, and once, in spite of criticism from other industrialists, shared a platform at a public meeting with Karl Marx. It is undeniable, however, that in A.C. Wood's memorably pithy phrase, Samuel Morley 'was never in any doubt about the importance of being earnest.'

Nottingham Corporation quickly accepted Morley’s offer, and in 1883 a separate library for children was opened in Shakespeare Street, just about a hundred yards along the road from the main library.

It was the first of its kind, and Samuel Morley had planted a tree that continues to bear new fruits. Unrecognized by most people, the old Children's Library building still exists in Nottingham, though not used for this purpose for almost seventy years now. If you stand with your back to the police building in Shakespeare Street, and look across to the University Extra-Mural Department, you will see at its left-hand end a modest gabled building with a little pyramid roofed tower. This was the library initiated by Samuel Morley.

SAMUEL MORLEY in old age.

SAMUEL MORLEY in old age.Such a busy life was bound to tell on an old man, and it was clear that Samuel Morley could no longer sustain a round of political, commercial, and philanthropic effort. His health had caused concern in 1880, though a visit to Canada and the United States a year later appeared to bring some improvement. However, he announced that he would resign his seat for Bristol at the general election of 1885. Immediately he did so, Gladstone wrote to offer him a peerage: 'I do not know that I have ever had a more genuine pleasure in conveying a proposal of this nature than now, when I make it to one who has earned so many irrefragable titles to the honourable regard and warm reverence of his countrymen. ’

Morley, typically, would have none of this. Though grateful for the offer, he was quite unattracted by the prestige attached to a title. Indeed, it was said of him that his public work had been so free of selfishness, that he would have been unwilling to appear to gain any personal advantage from it.

1 'Sneinton or Lady Bay?' Sneinton Magazine 69, 1998

2 ’Old Nottingham Suburbs.' Bell, 1914

3 James Ebrank Hall, builder and stonemason, of Carrington Street Bridge, was a prominent Sneinton figure throughout this period. In 1855 he lived in Belvoir Terrace (which, incidentally, he built,) but had moved to Colwick Road by 1860

4 A full account appears in 'A sight terribly grand: Sneinton's great fire of 1874.' Sneinton Magazine 29, 1988

5 See: A.C. Wood. 'Sir Robert Clifton'. Thoroton Society Transactions v. 57, 1953

(Part Two of this article will deal with the death of Samuel Morley, and describe how Nottingham determined to honour his memory.)

< Previous