< Previous

SNEINTON’S HOSIERY DYNASTY:

The Morleys of I & R Morley:

Part 2: Commemorating a philanthropist

By Stephen Best

(Part One of this article related the Sneinton origins of the firm of I. & R. Morley, and the company's development under the leadership of Samuel Morley.)

SAMUEL MORLEY as he appeared in his prime. From the Modern Owl of 4 August 1886.

SAMUEL MORLEY as he appeared in his prime. From the Modern Owl of 4 August 1886.IN THE SUMMER OF 1886 SAMUEL Morley suffered an attack of pneumonia. Though for a time he seemed to be rallying, he died at his home, Hall Place, near Tonbridge in Kent, on 5 September. On the following morning the Nottingham Daily Express reported that: 'Mr Morley had been ill for many weeks, and that some time ago his speedy demise was feared. He, however, survived the acute attack, and from time to time was reported to be making some progress towards recovery. His long illness at his advanced age, however, gave rise to serious apprehensions, which unhappily have been realised...'

Appreciations of Samuel Morley came from all parts of the country, and from political opponents as well as allies. Striking testimony to his qualities appeared just before his death, and again immediately after it, in a very unlikely periodical. Published in Nottingham, The Modern Owl was a humorous and satirical magazine. Frequently very outspoken, and capable of extreme effrontery when it detected a suitable target, it may be considered Nottingham's Private Eye of its day. What it said of Samuel Morley was a most arresting tribute to a remarkable man.

In its issue of 4 August, while hope still existed that Morley might regain his health, the Modern Owl published a cartoon depicting him as he had appeared in the prime of life. The accompanying paragraph speaks for itself: 'An unsuccessful appeal for any really deserving charity has never been made to him. Nothing perhaps tends so strongly to exhibit the true character of a great man, or extensive employer, as that of the way he treats his assistants or workpeople. A man may assume a virtue he does not possess, or in other words, he may play the hypocrite without, or before strangers, but he seldom does so at home or before those who are dependent on him for their livelihood. Measured in this way Mr Samuel Morley - to use the expression of one of his warehousemen - 'has a heart as big as an elephant.'... His life is one that should serve as a model to those who have means at their disposal, and many a home has been made happy... through the kindness of our great philanthropist... We could fill pages by recounting his deeds of work, but it would only be one long recapitulation of kindnesses bestowed, and the gentleman himself would not desire that we should seem fulsome in our recital of his good actions.'

When, only a few weeks later, news of Morley's death had been received, the Modern Owl observed on 8 September that: 'Our hopes were doomed to disappointment, and we are sorry to have to mourn his loss. Mr Samuel Morley won enormous wealth by carrying on a strictly legitimate business, and a great portion of that wealth was used by him in furthering the happiness of his fellow creatures... He gave both wisely and well, using brain, heart and purse unsparingly in his numerous charities, and his guiding principle throughout life seemed to be a 'strong desire to improve as much as possible the world he lived in. No man ever more truly recognised the great responsibility of being wealthy, and few have succeeded in carrying out that responsibility to its very fullest extent.'

The item closed with the hope that not only would a national monument be erected to him, but that Nottingham should also have some permanent and visible tribute to Morley.

Samuel Morley's burial took place at London's most important 19th century Nonconformist cemetery, Abney Park in Stoke Newington. Over twenty years later Morley would be joined there by another great man with the closest of Sneinton associations: William Booth. Among the many wreaths sent, two attracted much attention from newspapers. One was from a group of London flower-girls, whom Samuel Morley had helped save from a life of prostitution; the other was inscribed to 'Our kind and noble sahib,' from Indian orphans befriended by him.

His will revealed a personal estate of £474,000. In addition to legacies to members of his family, he left instructions that his executors had a moral obligation to fulfil all promises he had made to give towards the erection of places of worship and schools or colleges, and towards other educational and charitable projects. He also left money to maintain six chapels in Kent, whose building he had financed - Samuel Morley's name, and those of his sons, may still be seen on foundation-stones of chapels in Nottinghamshire and elsewhere. A characteristic Morley touch was a clause in his will leaving legacies to long-serving workers in his firm. These were on a sliding scale, rising to a substantial 19 guineas for employees who had been with I. & R. Morley for fourteen years or more.

Samuel Morley was rumoured to be the richest commoner in England of his day, and it is difficult to disagree with the opinion of The Modern Owl that this son of a Sneinton-born father was the exemplar of a man who used his money for the public good. Samuel's fourth son Arnold, born in 1849, maintained the family's strong link with Sneinton. Elected to Parliament in 1880, he was member for Nottingham for five years, then from 1885 to 1895 for Nottingham East, which included Sneinton. Arnold Morley was Liberal Chief Whip, and held cabinet rank as Postmaster-General for three years in the 1890s. A notable oarsman as a young man, he became an accomplished yachtsman.

Soon after Samuel Morley's death, the matter of a suitable memorial to him in Nottingham came under discussion, as The Modern Owl had hoped. A public meeting was held in December 1886 at the Albert Hall, at which the Mayor, Alderman John Turney, took the chair. Other notables present included the Duke of St Albans, Lord Lieutenant of the County: the Bishop of Southwell: and local MPs. A number of suggestions were put forward, such as a public hall for the free use of philanthropic organisations: scholarships to enable working-class children to continue their education for two years after leaving elementary school: and a block of almshouses. These were all acknowledged to be worthy proposals, but had the drawback of needing long-term financial commitment. It was therefore decided that a statue be erected in memory of Morley, and that a public subscription be opened towards this end.

The local community did indeed subscribe £1,500 towards the cost of a statue, and the Evening Post of 5 July 1888 was able to report that: 'The town of Nottingham is shortly to be enriched by the addition of a statue of the late Mr Samuel Morley. Mr Havard Thomas, the eminent sculptor, whom the Morley Memorial Committee commissioned to execute the work, having nearly completed his task. The site for the statue has also been decided upon, and is probably the best in the town, viz., at the top of Market Street, immediately in front of the Theatre.'

AN ARTIST'S IMPRESSION of the Nottingham Samuel Morley statue, 1888.

AN ARTIST'S IMPRESSION of the Nottingham Samuel Morley statue, 1888.The unveiling of the Morley statue was timed to coincide with a meeting in Nottingham of the Congregational Union of England and Wales. On the morning of the ceremony, 12 October 1888, about 200 delegates to the meeting attended a mayor's breakfast in the Exchange Hall. Speeches were numerous and prolix, beginning with one by the Rev. J. Guinness Rogers of London. This gentleman said that Samuel Morley, though gone, still lived among them, and that Nottingham did well to honour one who had done so many things for the town. The Rev. A. Mearns followed by remarking ruefully that the previous speaker had used all his best points. He had known Mr Morley since 1863, and recalled instances of his generosity, remembering that Morley had once told him he intended to give away £5,000 to the poorest in London, rather than to people who could built halls and chapels for themselves.

Speaking next, the Rev. Dr Henry Allon protested that, until entering the room, he had been unaware that he was going to be asked to speak. He nevertheless contrived to offer a lengthy vote of thanks to the Mayor. Acquainted with Samuel Morley for 45 years, Allon described how the great man would tactfully enquire about the financial circumstances of men joining the Congregational ministry, and see how he might best assist them. Morley had also 'rendered secret and substantial help to men with whose principles he did not agree... His heart, without any disparagement to the latter, was a great deal larger and bigger than his head.'

Samuel Hope Morley, eldest son of the man they were gathered to honour, spoke of the gratitude and pleasure felt by the family when they heard that 'Nottingham was about to perpetuate the memory of one who always had the deepest feeling of affection for the town.' The Mayor (again John Turney) replied to the vote of thanks, whereupon the official party, including the sculptor, left the Exchange and walked up to Theatre Square for the unveiling ceremony.

Here the dignitaries climbed on to a platform erected round the pedestal of the statue, and the Mayor invited Dr Bruce, Chairman of the Congregational Union, to open proceedings. Bruce observed that he knew of no man who was looked up to with more respect and affection than Samuel Morley. 'No man, whether warrior or statesman, was more worthy of a statue than he, and no man needed a statue less.' He considered that Nottingham, following Bristol, honoured itself in honouring this great and good citizen. Bristol had, during 1887, unveiled its own Morley statue, about which more will be said later.

Mr G.H. Atkin spoke next, on behalf of the industrial classes of Nottingham: 'If there are any individuals who are indebted to the memory or the labours of Mr Morley, surely we, who belong to those classes, may claim to have more largely than almost anybody else shared in the magnificent benevolence which he displayed during the course of his career.' Atkin believed that the statue would be not only a reminder of good deeds, but an inspiration to others to emulate Samuel Morley.

The Rev. J.H. Richardson, Vicar of St Mary's, then addressed the gathering in the absence of the Bishop of Southwell, recovering from a serious illness. He said that while he represented a religious body to which Samuel Morley had not belonged, he was one of the majority that recognised earnestness and goodness and spirituality in all men. Of the statue, he predicted: 'The smoke will fall upon it, the brilliance of the glittering marble will pass away, but the glory of Mr Samuel Morley's name will last for ever.'

The Mayor, in unveiling the statue, bore testimony to Samuel Morley's great qualities. He was glad that Nottingham had taken up the idea of erecting it, and that the town now possessed 'this beautiful work of art.' On behalf of the people of Nottingham he accepted the statue, and the onlookers cheered loudly when the oilcloth covering it slid away at the pull of a cord.

As one of the town's representatives in Parliament, Arnold Morley was very familiar with Nottingham. Like his brother, he expressed the interest felt by his family in the day's events, and congratulated the sculptor on 'the admirable and speaking likeness he has produced of Mr Samuel Morley.' He went on: 'I venture to think it will be a lasting ornament to the town, and I venture to hope that, standing as it does at the top of this street looking down over the busy Market Place, the active centre of the commerce of the town, and yet looking upwards as if looking for something higher than worldly matters, it will be an incentive and inducement to passers by to follow in the footsteps which he trod...' Arnold Morley added that the family believed that this memorial to their father had been given by the whole community, free from all party and creed factions; he thereupon proposed a vote of thanks to the mayor for his part in the occasion. In seconding this, Dr Paton of the Congregational Institute in Forest Road said that the subject of the statue was 'One of my dearest, my most intimate and sacred friends.'

Alderman Turney, doubtless aware that many of those present had already heard enough speeches for one day, concluded the formalities with a brief summary, praising Samuel Morley's munificence in contributing to the Children's Library, and to the Castle Art Museum. Had he wished to prolong the proceedings, he could have gone on to mention Morley's benefactions to, among other Nottingham institutions, the General Hospital, University College, YMCA, and High School.

This had been a memorable day for the town. If the occasion of Samuel Morley's death had given rise to national grief, then the unveiling of his statue had been very much Nottingham's moment.

THE STATUE OF SAMUEL MORLEY in Theatre Square. The Evening Post building is in the background.

THE STATUE OF SAMUEL MORLEY in Theatre Square. The Evening Post building is in the background.And what of the sculpture itself? The Nottingham Evening Post of 12 October considered that: 'Both as a work of art and as a piece of portraiture, the statue is of a high order of excellence.' The figure if Samuel Morley, in Sicilian marble, was eight feet high; it stood on a pedestal of red Aberdeenshire granite, with Morley's head eighteen feet above the base. Havard Thomas had depicted him in the act of speaking at a public meeting; the left foot was slightly advanced, and the right hand stretched out in a gesture of exhortation or appeal. Morley's other hand grasped the notes of the speech he was delivering. On the pedestal were carved the words: 'Samuel Morley, Member of Parliament, Merchant Philanthropist, Friend of Children, Social Reformer, Christian Citizen.' The inscription also recorded that the statue had been raised by public subscription. The memorial was elevated slightly above road level, on a flagged square, enclosed by posts at the corners. A lamp on either side illuminated it at night.

The Nottingham Daily Express was rather more guarded in its praise, reporting that: 'it appeared to be the general opinion yesterday that the work is a life-like presentment of the deceased gentleman.' It observed that Mr Morley was represented 'in the garb of nineteenth century conventionalism, apparently in the act of addressing an audience,' and made special mention of the 'exceedingly fine quality of granite,' perfect in colour and without any unsightly spots.

As already indicated, the Post thought particularly well of the statue, considering it 'full of character and force,' and likely to be 'generally regarded as a very successful example of the sculptor's art.' It was favourably contrasted with 'the inartistic 'counterfeit presentment" of Morley's old election opponent, Sir Robert Clifton. The statue of the latter, erected only in 1883, fourteen years after Clifton's death, was at that time sited at the top of Queen's Walk, opposite where the Midland station now stands. Its unveiling had immediately brought down obloquy on the head of its hapless sculptor, W.P. Smith of Peas Hill Road, Nottingham, and after Smith's death in a boating mishap at Mablethorpe in 1885, no one had been any more polite about his portrayal of Clifton. In 1904 the Clifton statue was immortalized by an article in the Strand Magazine. This charged it with possessing the worst pair of sculptured trousers in the kingdom, though the writer conceded that they were surpassed in ugliness by those adorning the Gambetta statue in Paris.1

From time to time further kind things were said about the Morley statue. The 1889 directory, for instance, judged it a 'well-executed statue in Sicilian marble' of a man 'of whose long and honourable business connection with the town, men of all parties are justly proud.'

Not everyone, however, was so impressed; Robert Mellors, the local historian, accountant, and county alderman, was later to write that 'both the stone and the site are unsuitable for their purpose.'

James Havard Thomas (1854-1921) had come from Bristol to London in 1875, and exhibited busts, statues and medallions at the Royal Academy. He worked in Paris from 1881 until 1885, and later in Capri. Havard Thomas was also the sculptor of the aforementioned statue of Morley in Bristol, which was, alas, characterised by the Dictionary of National Biography as 'bad,' and by a recent author as 'somewhat stiff and pompous.'2

Very similar in style to the Nottingham statue, though differing in detail, the Bristol statue represented Morley as extending his left arm towards the passer-by. The inscription recorded that over 5,000 local people had made a financial contribution to it: 'To preserve for their children the memory of the face and form of one who was an example of justice, generosity and public spirit...'

When the Morley statue in Nottingham was new, Theatre Square was undoubtedly a fine site for it. Even in the 1880s, though, this was a busy spot with many horse- drawn carts and cabs swirling around it. The twentieth century added the electric tram and the motor vehicle to the streets, and by the 1920s Samuel constituted an undeniable encumbrance to traffic. The City Council believed that another site might be found for the statue, which would free the flow of vehicles along Parliament Street, and at the same time provide the memorial with a more spacious and dignified setting.

Fierce objections greeted the proposal to move the statue from Theatre Square. No one appeared to consider that Samuel Morley deserved to share the ignominy of Sir Robert Clifton who, trousers and all, had been quietly shunted off to the Embankment at the turn of the century. In 1926, however, it was decided that the Arboretum would make an appropriate resting place for Morley, and it is hard to quarrel with this choice. A beautiful park close to the centre of Nottingham was, after all, still a place of honour. Local newspapers printed a photograph of the statue, superimposed on a background of its new location in the Arboretum. It all looked very handsome.

Just before Christmas the work of removing the statue took place. Insured against accidental damage, it was wrapped in sacking, and lifted on to a specially- constructed trailer, hauled by the machine breakers Clifton & Son, of Trent Lane. From Theatre Square it was taken to the Castle Boulevard yard of the stonemasons Pask and Thorpe, for a clean-up and safe keeping until the plinth and pedestal were ready to receive it in the Arboretum.

On the morning of 12 January 1927 all was ready. With the aid of a crane, the Morley statue was loaded on to a five-ton lorry at Castle Boulevard, for transport to its new home; the loading occupied just under two hours. The statue was stowed upright on the lorry, the property of R. Keetch, haulage contractor and coal merchant, of The Wells Road. It should be noted that no special trailer was provided for this trip, but the statue was ’well tied down with ropes,' and 'heavily timbered at the base.'

This ungainly procession set off at barely more than walking pace, but had got no further than Lister Gate when the statue was observed 'to be wobbling more than previously.' An eye-witness was later eager to tell the Nottingham Journal that it was apparent that the whole statue was topheavy even before the lorry had left Castle Boulevard, and that it had been rocking for some time.

Lister Gate having thus been precariously reached, the great Victorian was being trundled past Woolworth's. An onlooker, (who by an incredible, yet somehow inevitable, bit of Nottingham irony was a Mr Morley,) observed the parlous posture of the statue, calling out to the lorry driver: 'Mind! It'll be over!' And over it was, in an instant.

Samuel Morley, all one and a half tons of him, snapped off just above the ankles and 'came clean over with a crash,' damaging the left side of the lorry as he did so. The statue struck the carriageway head-first, leaving a considerable amount of powdered stone scattered alongside the tramlines. It was immediately clear that the right arm was broken off, and that the edges of the coat were damaged. The extent of further mischief remained uncertain, as the head and shoulders were swathed in sacking.

Police and tramway officials kept the crowds back and organized a single-line tram service past the stricken philanthropist, while men with pulleys laboured to lift the 'maimed statue.' The Journal rather pointedly noted that: 'It would appear that no official of the City Council was in charge at the time.' The police eventually sent for help to Oscroft's, the Castle Boulevard motor dealers, who brought their breakdown equipment to rescue the fallen Samuel Morley, and carted him off, back to Pask and Thorpe’s. Here it was ascertained that the nose of the statue had also been smashed to powder.

The paper concluded by reporting that no opinions on the feasibility of repair had yet been forthcoming. The Evening Post of the following day suggested that 'natural causes' might have played a part in the disaster, and that the Corporation were satisfied that the contractors were free from blame. They held the view that weathering over the years had caused the mishap, together with, the fact that the great weight of the statue had been borne by its comparatively slender legs. The paper wondered whether pedestrians had long been in danger of being overwhelmed as they passed the statue in Theatre Square at any time of strong vibration. Gales and heavy vehicles appear to have constituted the likeliest risks. No other statue in Nottingham was thought to pose a similar peril.

An Evening Post picture of the wrecked statue lying in Lister Gate, January 1927.

An Evening Post picture of the wrecked statue lying in Lister Gate, January 1927.The Post account on the day of the accident had been accompanied by a terribly murky and indistinct photograph, in which a group of idlers stand in a knot near the toppled statue. Men in cloth caps appear to be in solemn conversation, while in the foreground is a group of lads: errand-boys or newspaper sellers, perhaps. One of these appears fairly amused by the whole event, as he poses next to the shattered hero, who resembles a cross between Shelley's Ozymandias and a beached whale. It comes as no surprise to read that: 'The occasion was one for many jests - some kind and some otherwise.'

The Post reported the return of the wrecked statue to he stonemason's yard, 'Where, it is understood, it will be used as a copy for a fresh one of the late Mr Morley.' The paper went on to express the airy opinion that: 'The task of duplicating the effigy, with the original as a model, is not a particularly difficult operation.' The Post believed that there was no question of this being ruled out on grounds of expense, as the statue was insured.

In spite of press assertions that the contractors were not responsible, the reader may well have been wondering, like this writer, what kind of bungling clowns were in charge of loading the statue on to Keetch's lorry, and why the whole farcical business was not halted as soon as the statue was seen to be insecure in Castle Boulevard.

Such a downfall could hardly have attended the memorial of a more sober and respectable figure than Samuel Morley, and we may well conclude that this tragi-comedy constituted his second personal catastrophe in Nottingham, sixty-two years after his election misfortunes.

JOSEPH ELSE’S BUST OF SAMUEL MORLEY in Nottingham Arboretum. (Photograph: Stephen Best).

JOSEPH ELSE’S BUST OF SAMUEL MORLEY in Nottingham Arboretum. (Photograph: Stephen Best).Alas! the hopes of mending or reproducing the Morley statue came to nothing, though the eventual outcome was a very satisfactory one. Scaffolding remained in place for some considerable time at the projected Arboretum site, but it became clear that neither a repaired nor a copied statue would be feasible. It was decided instead to replace the statue with a bronze bust. This was accordingly executed by the accomplished Joseph Else, principal of Nottingham College of Art, and a native of the town. Else remains an under-appreciated figure, his name unknown to many, yet he provided Nottingham with some of its most notable twentieth century public art.

He made an enormous contribution to the new Council House, being responsible for one of the groups of statuary around the dome, and for the figures in the pediment representing aspects of the arts and public endeavour. Else also created the frieze behind the portico, depicting old industries of Nottingham, and those celebrated symbols of lovers' meetings, the lions. Another of his works in the city is a statue of St Luke on the Nottingham Society of Artists building in Friar Lane, and his London commissions included the Law Society war memorial, and decorations at Selfridges. Nottingham was lucky to have Joseph Else, and it was fortunate that Samuel Morley's new memorial fell into such capable hands.3

Else worked from photographs and engravings of Morley, and it was widely agreed that his bronze bust bore a closer resemblance to the great man's features than the afflicted statue it replaced. The new bust, set in place on 12 December 1928, is located close to the lower gates of the Arboretum. Standing on a tall slim pedestal, with curved seats on either side, it deserves more attention and praise than it generally receives nowadays. For all his vicissitudes, Samuel Morley still has an appropriate memorial in Nottingham.

Morley's Bristol statue has had better luck than its Nottingham counterpart, in spite of having been twice relocated because of traffic requirements and urban development. It survives in the City Centre there, having recently escaped banishment to an out-of-town shopping park. Though suffering no calamity to compare with the Nottingham statue disaster, it was, shortly before its latest move, subjected to its own ludicrous indignity. In July 1997 it was adorned with a pair of colourful trousers for Wrong Trousers Day, marking Wallace and Gromit's Grand Appeal for the new Royal Hospital for Children. Although this fund-raising cause would undoubtedly have earned Samuel Morley's approval and support, it is hard to imagine the old gentleman being amused by comical trousers clothing his statue. But then, one wonders, would Samuel Morley really have approved in the first place of the erection of any statue to his memory?

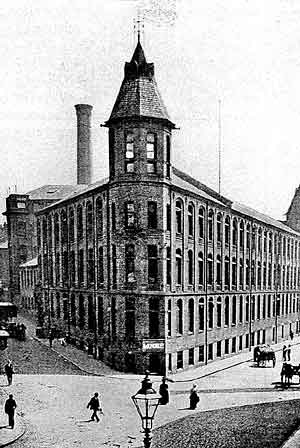

I & R MORLEY'S FACTORY about 1899 in Manvers Street, Sneinton. The building was badly damaged in an air raid in 1941, some years after Morley's had moved out, and still survives in its post-war reduced state.

I & R MORLEY'S FACTORY about 1899 in Manvers Street, Sneinton. The building was badly damaged in an air raid in 1941, some years after Morley's had moved out, and still survives in its post-war reduced state.In conclusion, we return to the three questions raised at the outset of this article, in the hope that they have been satisfactorily answered. It is clear that Samuel Morley was, by intimate family ties, and by virtue of his local factories, a very significant Sneinton figure. It may be assumed that the brewers' publicity people chose him as the new name for the Turf Tavern on discovering that Samuel Morley's statue had for years stood on a site a few yards from the pub door. It also seems likely that they had not the faintest idea of what Samuel Morley stood for, nor did they trouble to find out. At least one hopes this was so; the alternative is hardly credible, that a brewery should consciously set out to offend the memory of a distinguished leader of the temperance movement. Whatever the reason, the naming of the pub after Morley was a lamentable own goal.

Lest it be imagined that I have anything against pubs, it may be mentioned that it was in the Turf Tavern that I asked my wife to marry me. And a second personal observation is unavoidable here, too. Throughout this brief account it has been demonstrated that Nottingham owed much to Morley and his firm. I share in this general indebtedness, as my mother and father met in the 1920s at the Fletcher Gate factory of I. & R. Morley, where they both worked.

This brief history is inscribed to the memory of Keith Train, from whom I learned so much about Nottingham history. Keith used to recall that January 1927 saw, not only the downfall of the Morley statue, but also the beginning of his long teaching career at High Pavement Grammar School.

As always, my thanks go to Nottingham Local Studies Library, and on this occasion I am very grateful also to Miss D. Dyer of Bristol Central Library for her help. Not least, my stepson Stewart, now a Bristol resident, diligently hunted down the Samuel Morley statue there, and sent me details of its inscription.

In addition to sources mentioned in the course of the text, the following have been of great assistance to the writer, and are gratefully acknowledged.

Beckett, John (ed.) 'The centenary history of Nottingham.' Manchester U.P., 1997. (Stanley D. Chapman's chapter 'Industry and trade, 1750-1900' has proved invaluable.)

Bradley, Ian. 'Enlightened entrepreneurs.' Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987. (It contains perhaps the best and most accessible brief account of Samuel Morley, and includes another chapter of Nottingham interest on Jesse Boot. Recommended to the general reader.)

Hodder, Edwin. 'Life of Samuel Morley.’ Hodder & Stoughton, 1887. (By a friend of Morley, this is perhaps over-long and too hagiographical for modern tastes. Those who are not devoted students of Morley will probably find Bradley a preferable source of background information.)

Thomas, F.M. 'I. & R. Morley: a record of a hundred years.’ Chiswick Press, 1900.

1 See: 'Our brown stone ugly duckling.' Nottingham Civic Society Newsletter 97-99, 1992

2 B. Little. 'Bristol, the public view.' Redcliffe Press, 1982

3 See: 'Take a look at Joseph Else's legacy.' Nottingham Civic Society Newsletter 61, 1983

< Previous