< Previous

‘A WANDERER IN SNEINTON’:

Part 1: Once more let us quit the town

By Stephen Best

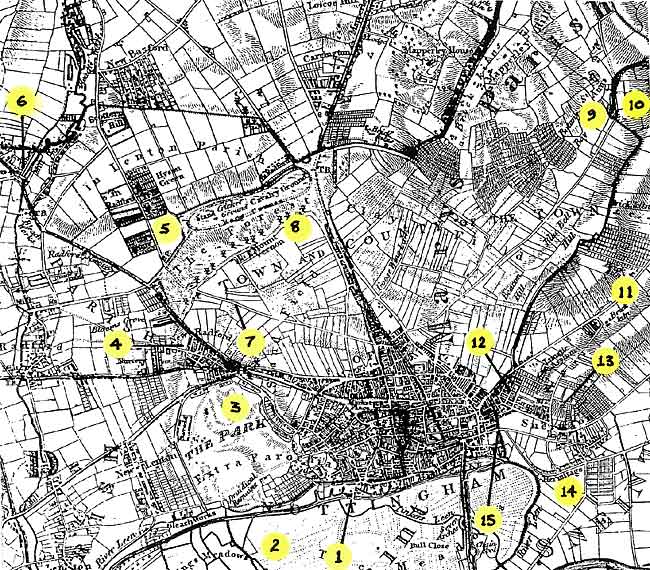

Some of the places mentioned in this article, shown on SANDERSON'S MAP. Surveyed between 1830 and 1834, it was published in 1835, the year that Walks in Nottingham appeared.

Some of the places mentioned in this article, shown on SANDERSON'S MAP. Surveyed between 1830 and 1834, it was published in 1835, the year that Walks in Nottingham appeared.

1. Navigation Inn, 2. The Meadows, 3. The Park, 4. New Radford,5. Hyson Green, 6. Bobber's Mill, 7. Larkdale, 8. Forest Road, 9. St Ann's Well, 10. Approximate site of the Shepherd's Race, 11. Carlton Road, 12. New Sneinton, 13. Green's Mill, 14. Sneinton Hermitage, 15. Pennyfoot Stile.

ALTHOUGH SNEINTON WAS OFTEN ignored in pre-Victorian accounts of Nottingham and its neighbourhood, a writer of the 1830s included a brief sketch of it in a book that still contains much of interest to any student of the area's history. Walks Round Nottingham, by A Wanderer, was published in 18351; we shall learn something about its author in due course.

The book was written, so the preface explained, 'with the declared object of exciting some degree of attention to antiquarian researches.' Its writer felt 'satisfied that his unpretending little work will be the means of rescuing many occurrences of past times from oblivion.' He also hoped that the volume would provide his readers with instruction, amusement, and satisfaction.

The author's coverage of places around Nottingham was unevenly distributed, but his plan had been to visit locations with a particularly interesting history. To the west of Nottingham he ranged as far afield as Strelley, and to the east his trips extended to Shelford. South of the town he ventured out considerably further, to Bunny. By contrast, he did not go much beyond the Forest on the northern fringes of Nottingham.

It is arguable that his accounts of the outskirts of the town are the most fascinating aspect of Walks Round Nottingham. 'A Wanderer' left his impressions of these areas in the last few years before the passing of the Inclosure Act allowed building on the common lands surrounding Nottingham, and gradually but irresistibly drew the town out towards the settlements that would in 1877 become part of the borough - Radford, Lenton, Basford, Bulwell, and not least, Sneinton. Before seeing what he had to say of Sneinton, it is worth noting some of his observations on other places now long subsumed in the built-up city.

Beginning with the south side of the town, he wrote of The Meadows: 'How delightful it is, when wearied with the bustle and the noise of business, to escape from the narrow streets filled almost to suffocation with buildings, and to spring over the bridge near the Navigation Inn, bursting at once upon nature, arrayed in her richest verdure...'

The inn stood where its rebuilt and recently renamed successor, the Lock and Lace, still stands, on the canal bank in Wilford Street, only a few yards south of today's Castle Boulevard. It is quite an effort to imagine how closely the open countryside came up to the town here. Within five years, however, the railway from Derby would drive across it to its first Nottingham terminus, just across the canal. 'A Wanderer' recorded that 286 acres of the Meadows were commonable to the Burgesses of Nottingham, who, at varying times of the year, could each graze three head of cattle or 45 sheep on the fields.

To the west, the author commented on the earliest houses built in The Park, 'a charming and healthy spot for recreation.' These houses, however, by no means met with his approval. 'At present the designs are multifarious, and many of them peculiarly awkward in appearance - some shoot up in assinine deformity, others are squat and low as if some great monster had sat upon them, and crushed the ground floors below the earth.' Beyond The Park, 'A Wanderer' reported that Lenton was still 'a quiet retired village, and now of little note.'

In Radford significant change had already taken place: 'The whole of the ground between the Nottingham sand fields and the Derby Road, now covered with buildings, including Islington, New Radford, Bloomsgrove, &c. in this parish, was before the year 1796, occupied principally as gardens for the Nottingham market.' This was the land between Alfreton Road, Ilkeston Road, and Derby Road, immediately beyond Sion Hill (now Canning Circus.) Islington was an alternative name for New Radford, while Bloomsgrove lay close to what became Denman Street. Like Blue Bell Hill and Peas Hill, the name Bloomsgrove gives some indication of the floral nature of the fringes of Nottingham 200 years ago.

Although one house was erected some years earlier, Hyson Green had begun to be built up about 1820, and the nearby Bobber's Mill had by the 1830s become 'an increasing hamlet to Radford.' It contained 'some neat cottage residences, and, in appearance, a respectable Public-house.'

This was the old Wheat Sheaf - a later pub of the same name continues in business in Nuthall Road, opposite the foot of Aspley Lane.

Barely a mile north of the Great Market Place lay the Forest, and in 1835 the road to it was still unspoilt and picturesque. In describing it, 'A Wanderer' again gave himself up to lyricism. 'But let us quit the town, and at once enjoy the pleasures of a country lane, by passing through the Larkdell, embowered as it is with high banks and arching foliage.' The Larkdale, whose course can be located by the present-day Larkdale Street, ran up to the Forest ridge a short distance west of the wider and more important Lingdale, represented since the middle of the nineteenth century by Waverley Street.

(The editors of the printed Borough Records suggested that the Larkdale and Lingdale had been rather differently located, but the local antiquarian James Granger, in a closely argued account, written from firsthand knowledge, was adamant that they had made an error.)2

Reaching the crest of the hill where Forest Road now runs, 'A Wanderer's’ eloquence continued: 'A wide expanse of hill and dale, of grove and pasture - of humble cottage, and lordly mansion, presents itself, together with a new town spreading over a considerable space of ground, occupied by the children of industry, and coal mines, and cultivated fields. Along the brow of the declivity is a range of windmills, which, I am told, may be seen from a lofty eminence on the borders of Yorkshire.'

One can readily accept that from the Forest ridge he would indeed have been able to see the growing Radford, Hyson Green, Basford, Carrington, and even Bulwell. It is, however, less easy, to be convinced by the claim that the windmills here could be seen from Yorkshire, over thirty miles away. This was, as the reader will have noted, hearsay evidence only, and the present writer would like to know where the 'lofty eminence' on the Yorkshire border might have been.

Moving round to the north-east, the book went on to describe St Ann's Well, then in open and unspoilt countryside beyond the tract of open fields called the Clayfield. The road to the well led from Beck Barn (now Beck Street,) 'A Wanderer' mentioning that within a short distance of setting out on his walk he had passed the new burial ground, opened only three years earlier during a cholera outbreak. This was St Mary's Cemetery, formerly Fox’s Close, largely cleared of memorials over fifty years ago, and now the public rest garden at the corner of Bath Street, in which a carved lion marks the grave of William Thompson, the celebrated bare-knuckle fighter Bendigo.

Walks Round Nottingham repeated some improbable stories linking St Ann's Well with Robin Hood, but no doubt its readers were happy to be assured that 'there is every degree of probability that this was a rendezvous for Robin Hood and his merrymen... ’

Plan of the Shepherd’s Race maze, reproduced 28 years after its destruction, in THE MIRROR OF LITERATURE, AMUSEMENT AND INSTRUCTION of October 1825.

Plan of the Shepherd’s Race maze, reproduced 28 years after its destruction, in THE MIRROR OF LITERATURE, AMUSEMENT AND INSTRUCTION of October 1825.'A Wanderer' lamented the disappearance in 1797 of the nearby Shepherd's Race turf maze. This had lain on a hillside 'half a quarter of a mile' east of St Ann's Well, on what was known as Sneinton Plain or Sneinton Common, between where The Wells Road and Porchester Road run now. Shepherd's Race (sometimes Robin Hood's Race) had been ploughed up nearly forty years before, at the time of the Sneinton Enclosure Act. It is often forgotten that Sneinton parish once extended as far this, but the extreme northern tip of the parish used to stick out out in a kind of stubby panhandle between the outer limits of Nottingham and Gedling.

About seventeen feet in diameter, excluding the four projecting features visible in the plan reproduced here, the maze was among the more remarkable vanished features of Sneinton, and one whose loss is deplorable. As the book related: 'it was cut out of the Turf, and seems to have been formed as a place of exercise, and there are very few persons, of forty-eight years and upwards, who have not been taken by their parents and friends to run the Shepherd's Race...' A number of theories have been put forward over the years as to the antiquity of the maze, and whether it had religious or ritual significance other than as a place of simple recreation.3

By the 1830s a miniature replica of the Shepherd's Race had been laid out close to St Ann's Well. Walks Round Nottingham rather strangely made no mention of this; perhaps 'A Wanderer' visited the place just before it was cut, or remained unaware of its existence? James Granger4 remembered running the course of this later turf maze, stating that it had disappeared in 1873 or 1874.

Yet another imitation of the Shepherd's Race was recorded by the antiquarian William Stevenson. This seems to have been in either Holly Gardens or Thorneywood Rise, not far from the site of the original. Stevenson recalled that it was in a garden in 'one of the long avenues stretching from Carlton Road and running parallel with Thorneywood Lane, and was occupied by a Mr and Mrs Poynton, at which time it was known as Poynton's Tea Garden '

It is a beguiling thought that, at various times, Sneinton had two turf mazes within its boundaries, with a third only yards outside. Two surviving mazes of this kind, both of considerable antiquity, are within an easy drive from Nottingham. At Wing in Rutland the maze is by the roadside, while that at Alkborough in north Lincolnshire has the added attraction of being cut into a high hill overlooking Trent Falls, where the River Trent joins the Yorkshire Ouse to form the Humber estuary. A visit to either is well worthwhile.

Still on the fringes of Sneinton, the author observed that: 'There are several other pleasant walks through the lanes on the Carlton road, and also to what is termed the Hunger-hills, from the summit of which, is a most extensive and beautiful view.'

Having travelled clockwise around the edge of Nottingham from south to east, rather than following the rather more erratic order in which 'A Wanderer' arranged his walks, we now arrive at the short section of his book which deals with Sneinton proper. He spelled it 'Snenton,' as many did at that time - one great advantage of that form must have been that anyone seeing the name in print would, without ever having heard of the place, immediately know how it was pronounced.

One thing immediately noticeable in his account is the absence of any mention of New Sneinton, the rapidly growing settlement lying between Nottingham and Old Sneinton on its hill, with the windmill and church. It would have been understandable had our author commented on New Sneinton, if only to deplore the drastic effect it was having on the picturesque old village, and it seems odd that he ignored altogether the fact that Sneinton was changing so dramatically - its population in 1841 would be twelve times as great as in 1801. He was, though, as we need to remind ourselves, chiefly concerned to pick out spots with an historical story to tell.

The reader of 2002 may be surprised to find no reference to the windmill, or to George Green, but the reasons for this are simple. The windmill was then one of many such features of the agricultural and industrial scene; a far less unusual and picturesque element of the landscape than we consider it today. As for George Green, his name would in 1835 have been known only to those sufficiently versed in mathematics and physics to realise that he was a significant figure. Green's first book, An Essay on the Application of Mathematical Analysis to the Theories of Electricity and Magnetism, had been published in Nottingham seven years earlier, in 1828, but there can have been few in the town who were aware of it, let alone able to understand any of its reasoning. Apart from that volume, Green's only other writings thus far published had been three papers in the transactions of learned societies.

Walks Round Nottingham also came too soon to include any anecdote about Sneinton’s other great celebrity, William Booth, who was at that time only six years old. In 1835, the year of the book's appearance, the Booth family returned to Sneinton to live in West Street, after four years on a smallholding at Bleasby. They had been obliged to give up their Notintone Place house in 1831, following Booth senior's failure in business.

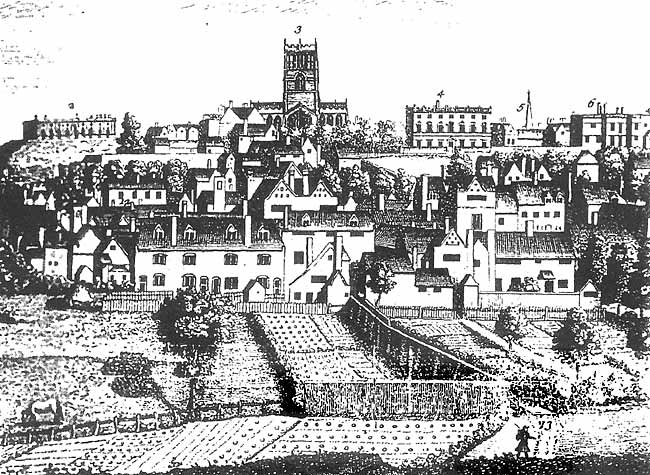

THE PENNYFOOT STILE in the mid-eighteenth century, from Deering's History. The figure in the foreground approaches the stile from the Sneinton side. A narrow path leads to Carter Gate. On the skyline are the Castle, St Mary's Church, Plumptre House and Pierrepont House.

THE PENNYFOOT STILE in the mid-eighteenth century, from Deering's History. The figure in the foreground approaches the stile from the Sneinton side. A narrow path leads to Carter Gate. On the skyline are the Castle, St Mary's Church, Plumptre House and Pierrepont House.''A Wanderer’ was yet again in poetic mood for his outing to Sneinton. 'Once more let us quit the town. It is a lovely day early in the month of June, the sky is clear and bright, the sun is shedding his delightful influences, and a pleasant breeze tempers the heated atmosphere. Now let us pass the spot known as Penny-foot stile, which in all probability derived its name from Poana-ford stile, Poana being the old British or Celtic word for painful, or difficult, so that this might have been called 'the Stile by the difficult ford,' it being close to the Beck or Brook which separated the town liberties from those of the county.'

The Beck, long since culverted underground, still flows beneath the bus garages in Manvers Street, across Pennyfoot Street, with an outfall into the Trent at Trent Lane. At Pennyfoot Stile pedestrians used to negotiate this small, though significant, stream. It has been suggested that when the boggy state of the path in wet weather first necessitated the provision of a raised platform, a toll of a penny was perhaps levied, giving rise to its name.5 This alternative derivation may seem more likely than the one offered by 'A Wanderer.'

The present-day Pennyfoot Street runs on either side of the site of the stile. Denison's Mill, whose dramatic destruction was described in an earlier Sneinton Magazine,6 once stood on the Nottingham side of Pennyfoot Stile. According to Walks Around Nottingham: 'The stile was at the extremity of the houses.’ These dwellings were the last buildings within the boundaries of the old Borough of Nottingham. On the other side of the Beck, across the stile, lay Sneinton parish.

Charles Deering's history of Nottingham, published in 1751,7 but written several years earlier, contained an 'East Prospect of Nottingham' by Thomas Sandby which shows Pennyfoot Stile. Drawn perhaps a century before 'A Wanderer' visited the spot, it shows the open country once existing between Nottingham and Sneinton. A narrow track, fenced on one side, leads between gardens to the stile, with St Mary's church on the hill behind. Below the church, in Carter Gate, are the houses on the eastern edge of the town. The stile appears to have had a deck of wooden planks to enable pedestrians to cross the stream into Sneinton.

'The lanes in the neighbourhood,' continued Walks Round Nottingham, 'are extremely rural. In one leading to the right, from Snenton Church, there is a very pleasing view of the town, and at night, when the great window in St Mary's Church is lighted up, the scene is highly romantic.'

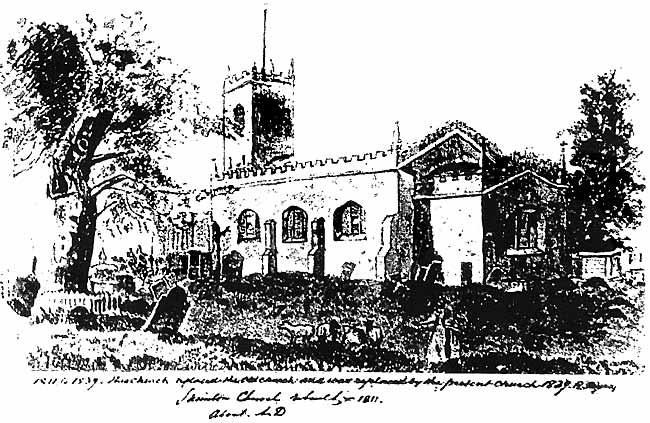

The author made his way up the lane just mentioned (now Newark Street) for a look at Sneinton church. A few lines, however, sufficed for all he wanted say to about this building: 'Snenton old Church was pulled down, and the present one being erected on the scite, was opened for divine service in October, 1810. It is a plain and neat edifice, dedicated to St Stephen, with a fine old tree near it, part of which was destroyed by the friction of the branches setting it on fire during a gale of wind, in the winter of 1826.'

SNEINTON CHURCH as visited by A Wanderer: a view by a contemporary artist. The dates written below suggest that the opening of the building took place in 1811, not 1810.

SNEINTON CHURCH as visited by A Wanderer: a view by a contemporary artist. The dates written below suggest that the opening of the building took place in 1811, not 1810.This little church had an undistinguished life of fewer than thirty years, during which time few complimentary things were written about it. A couple of decades before 'A Wanderer' described it, Laird's Beauties of England and Wales , in the course of a short passage on Sneinton, had remarked that: 'the chapel is small and low, partly in the Gothic style, but having nothing to recommend it particularly to notice, except the very extensive prospect over the vale of Belvoir, and even as far as the 'Leicestershire forest rock,' at a distance of twenty miles.' 8

Brick-built, with a modest west tower, it had replaced a very small church which was ancient in the manner of the hatchet which had been used by a family for generations, receiving only four new heads and three new handles during its life. This second church was supplanted in 1839 by the church whose central tower remains as the landmark of Sneinton parish church; the body of the building, however, was rebuilt round it in the first dozen years or so of the twentieth century. The church we see today should therefore be considered the fourth parish church on the site.

Some uncertainty exists about the date of the first service in the second church. October 1810 has often been quoted, but a notice appeared in the Nottingham Journal of 10 November 1811, referring to the holding of Divine Service in the newly-opened church. This was conducted by the Rev. Dr Robert Wood, who, although described at times as 'Vicar of Sneinton,' was in fact its assistant curate - between 1806 and 1817 the perpetual curate of Sneinton, the Rev. Richard Cox, lived nearly twenty miles away, at Kneesall.

Wood was also, at different periods in his life, chaplain to Nottingham Gaol: vicar of Cropwell Bishop: and usher, then master, of Nottingham Free School in Stoney Street (predecessor of Nottingham High School.) His career at the school was far from satisfactory, marred by eccentricity and cantankerousness, but the authorities there were unable to get rid of him until he was 73. He lies buried beneath a plain flat gravestone in Sneinton churchyard, east of the church, and four or five yards from George Green's grave.9

(Part 2 of this article will describe 'A Wanderer's' visit to Sneinton's most picturesque feature, and give an outline of his remarkable life.)

REFERENCES

1. London: Effingham Wilson, and Simpkin & Marshall. Nottingham: T. Kirk & S. Bennett

2. Nottingham: its streets, people &c.: 1st and 2nd series. Nottingham Daily Express, 1902-04

3. The following are of interest:

R.W. Morrell, Nottingham's mysterious mazes. Nottingham: APRA Press, 1990

Felix Oswald, The St Ann's Well maze; its probable origin and date. Transactions of the Thoroton Society v. 51, 1947

W. Stevenson & A Stapleton, Some account of the religious institutions of old Nottingham: 3rd series. Nottingham, Thomas Forman, 1899

4. Granger: op cit

5. Robert Mellors, The gardens, parks and walks of Nottingham and district. Nottingham, J. & H. Bell, 1926

6. Supposed to be done on purpose: the destruction of Denison's mill. Sneinton Magazine 23, Winter 1986

7. Nottingham vetus el nova. Nottingham, G. Ayscough and T. Willington, 1751. Reprinted by SR Publishers, 1970

8. Francis C. Laird, Beauties of England and Wales: v. 12 pt 1. London, printed for Sherwood, Neely & Jones, 1813

9. Tales from St Stephen's churchyard: scholars, smiths and others. Sneinton Magazine 30, Spring 1989

< Previous