< Previous

‘A WANDERER IN SNEINTON’:

Part 2: The Rosy, Hearty, Heroic ‘Old Sailor’

By Stephen Best

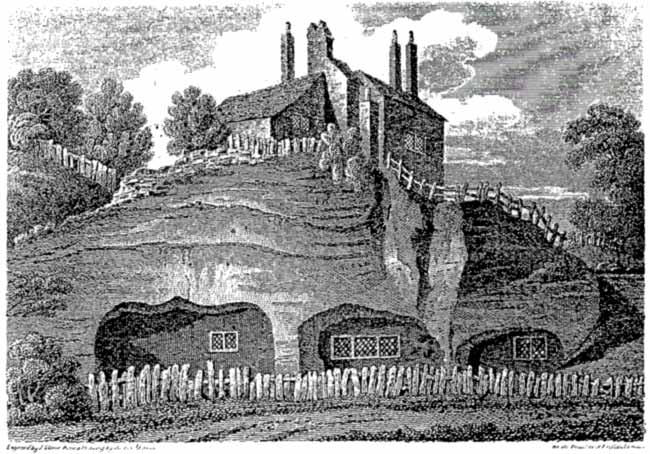

SNEINTON HERMITAGE about 1810. An engraving by J. Storer for Beauties of England and Wales.

SNEINTON HERMITAGE about 1810. An engraving by J. Storer for Beauties of England and Wales.(Part 1 of this article followed the footsteps of 'A Wanderer,' as described in his Walks Round Nottingham, published in 1835. We rejoin him as he leaves Sneinton church.)

FROM THE CHURCH ’A WANDERER' made his way back to Pennyfoot Stile, and then turned his attention to the feature of Sneinton he had really come to see - the Hermitage. Pointing out on the way two large arches in the rock face of the cliff, he arrived at the White Swan public house. 'Here a noble dancing room is partly cut in the solid rock, and there were formerly several recesses thus formed. Indeed a mistaken notion seems to have prevailed that however much a rock may be undermined it is still a rock, and therefore can never fall.’ But it had indeed fallen, merely six years before this date, in one of Sneinton's most dramatic incidents. A fuller account of this appeared some years ago in Sneinton Magazine,1 but the story is worth repeating briefly here.

The Hermitage had long been the most widely known picturesque attraction in Sneinton, with houses and other buildings built into the south-facing sandstone cliff. First mentioned in 1518, the Hermitage retained its dwellings until late in the 19th century. A couple of pubs also survived until the 1890s, the White Swan already referred to, and the Manvers (latterly Earl Manvers) Arms.

Laird's 1813 narrative2 had left a most agreeable picture of Sneinton: The village itself is rural, at present in some part romantic; has a number of pleasant villas and cottages, and has long been famous for a race of dairy people, who make a very pleasant kind of soft summer cheese.' Laird had also given a lively description of the Hermitage: 'Great part of the village indeed, consists of the habitations within the rock, many of which have staircases that lead up to gardens on the top, and some of them hanging on shelves on its sides. To a stranger it is extremely curious to see the perpendicular face of the rock with its doors and windows in tiers, and the inhabitants peeping out from their dens, like the inmates of another world...'

On 10 May 1829 this idyllic-sounding spot witnessed a most alarming rock fall, which followed one of 13 April on the rock face below High Pavement and above Narrow Marsh. In the very early hours of Sunday morning a Mr Flinders, who lived next door to the White Swan, was awakened by the fall of a large lump of rock into his garden, but: 'Not apprehending any danger, he again went to bed, but had scarcely laid down, when a quantity of the cliff gave way, and broke through the roof of the White Swan, kept by Mr Eyre.' Both households very prudently vacated their premises, but after an hour or two Flinders was minded to return home. Just at this moment, however, 'The whole face of the rock rent off from the main body, and totally buried his house, so as not to leave one vestige of its sight, and the habitable part of Mr Eyre's was also much beaten in and destroyed.' No one was injured, but the properties were wrecked. It was reported that on the next day thousands of sightseers came to Sneinton to gape at the devastation.

The Nottingham Journal reckoned that the fallen section of rock had been some 25 or 30 yards along, five or six yards thick, and perhaps 30 to 40 feet in height. With such a tonnage falling on to the houses, it was astonishing that no one had been killed. The Lord of the Manor, Earl Manvers, ordered that the cliff face be made safe, and the most obviously dangerous overhanging portions of rock at the Nottingham end of the Hermitage were cut away.

The work of securing the rest of the Hermitage cliff face was still in progress when a further fall occurred on 9 July. This time the other pub suffered most damage: Earl Manvers might well have pondered the irony of the rock falling on the inn bearing his name just as he was taking measures to prevent a repeat of such a disaster.

'A Wanderer' duly recorded this second Hermitage mishap: 'A man who had been standing on the rock narrowly escaped falling with it, and Mrs Seymour, the landlady, who was in the lower apartment of the house, was nearly buried in the ruins, and received several severe contusions upon the head, but she was speedily extricated without sustaining any other injury, and soon recovered. Both public houses have since the accidents undergone considerable repairs, and are now much improved. At the Manvers' Arms the dancing room is entirely in the rock.' We may feel that Mrs Seymour's injuries were rather lightly dismissed, but, like others in the earlier rock fall, she was undoubtedly very lucky to escape with her life.

These dramatic happenings evidently did little to diminish the striking impression made by the Hermitage on visitors. It was still a remarkable sight in 1835, as Walks Round Nottingham attested: 'Several of the houses have their entire suite of apartments formed by excavations in the cliff, having the front of brick work, with windows, and in some places, one house is actually standing above the summit of another.'

The title page of Walks Round Nottingham. Broxtowe Hall was demolished not long before the Second World War.

The title page of Walks Round Nottingham. Broxtowe Hall was demolished not long before the Second World War.In the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the Hermitage was transformed by the arrival of the railways. During the 1880s the rock at the town end of its northern side was lowered and levelled to make possible the building of the London & North Western Railway goods station in Newark Street3 A high embankment was constructed south of the road to carry the goods branch over the Hermitage from Trent Lane Junction, causing the disappearance of such Sneinton landmarks as Lund's Gardens at the Colwick Road end of Meadow Lane. In the nineties the diversion of the Great Northern line into the new Victoria Station involved the erection of a long viaduct, and the consequent diversion of the Hermitage carriageway to a new location some twenty yards north of its old course. Towards Hermitage Square the row of tall and handsome villas, still in existence, was built in 1905.

Recent developments have now obliterated almost every trace of the impact of the Victorian railway on Sneinton Hermitage. All is much cleaner and blander now than it when this writer first knew the spot, but most of the the distinctive character of this grimly atmospheric street has gone for ever.

Leaving the Hermitage behind him, 'A Wanderer' continued in an easterly direction, passing 'the house which formerly belonged to Mr Mellors, the banker; it is in a retired situation, and that is the only thing of which it can boast.'

The exact location of this vanished house, lying somewhere east of Meadow Lane along the Colwick road, has so far proved elusive. Charles Mellor (not Mellors) was quite a notable figure in the town, and it is rather surprising that his name has not cropped up before in Sneinton Magazine. He appears in the Nottingham poll books of 1812 and 1820 as a country voter in the whig cause, living at Sneinton. Owner of property in High Pavement, he was in 1808 a founding partner in the Nottingham bank of Fellows, Mellor & Hart. Following Mellor's departure from the business in 1818, the bank became Hart, Fellows & Co., and was in 1891 taken over by Lloyds Bank. The former Hart, Fellows bank building in Bridlesmith Gate was for a number of years the local office of Sun Alliance, but is now the Cafe Rouge restaurant. A churchwarden of St Mary's, Mellor was a visitor to Nottingham General Hospital. A member of the Commission on the new General Lunatic Asylum in the town, he was an original shareholder in Nottingham Subscription Library and gave financial support to the Lancasterian School, the Sunday Schools, and the Institution for the Relief of the Sick Poor.

'A Wanderer' had now finished his Sneinton observations. After walking a short distance further along the Colwick Road, he approached one of the lodges of Colwick Hall. We may return to his account of hall and church at Colwick in a future Sneinton Magazine.

Now, at long last, we turn to the identity of 'A Wanderer,' the man responsible for Walks Round Nottingham. Although not a native of the town, Matthew Henry Barker was for over a decade a prominent figure in Nottingham; a busy man with a colourful past. 'A Wanderer' was not the only nom de plume under which Barker wrote. With considerable justification he also styled himself 'The Old Sailor,' by which name he became very well known. It has been suggested that he was also the writer who went into print under another nautically inspired disguise, that of 'Bowman Tiller.'

Born in Deptford in 1790, the son of a dissenting minister, Barker went to sea as a lad of sixteen on board an East Indiaman, but later joined the Royal Navy. Although some later writers were to remember him as Captain Barker, he never had sufficient money or private influence behind him to achieve promotion beyond the rank of acting-master, which post he held on the gun-brig Flamar. Leaving the Navy, he acquired the command, at the age of 23, of the True Briton, a 'hired armed schooner' - that is to say, a privateer. Aboard this vessel he was engaged during the Napoleonic Wars in carrying despatches to and from squadrons of the Royal Navy at sea off the coast of France and Spain. On one occasion he fell into enemy hands, and was held for a brief period as prisoner of war. (Given his irregular military status, he was perhaps somewhat fortunate to be treated as such.)

At the end of the war, Barker turned to writing as his source of income, and, in addition to a number of books, wrote pieces for a variety of periodicals, including the Literary Gazette, Bentley's Miscellany, the Pictorial Times, and United Services Gazette. He was naval editor of the last-named. He died in Deptford, his birthplace, on 29 June 1846, aged 56. According to his entry in Ward's Men of the Reign, he never earned enough to do much more than barely support his family, and died in poverty and misery. This was no exaggeration. As we shall hear, some aspects of Barker’s life, and the circumstances surrounding his death, were pitiful in the extreme.

The titles of some of his published books clearly indicate their nature. Jem Bunt: Life of Nelson: The Log Book, or Nautical Miscellany: The Quarter-Deck, or Home and Abroad: all these were published under the name 'Old Sailor.' Barker was also celebrated for his Old Sailor's Jolly Boat, published originally in twelve parts by Jonathan Dunn in Nottingham during 1843 and 1844.

In 1825, Matthew Henry Barker was appointed editor of a newspaper in the West Indies, but came the following year to Nottingham as assistant to William Powers Smith, editor of the Nottingham Mercury, soon to be renamed Nottingham and Newark Mercury. Within a year Barker had succeeded Smith in the editorial chair, which he filled until 1839. This was one of four weekly papers published in the town in 1825. Of these the Nottingham Journal represented the tory view, and the very radical Nottingham Review the opposite pole. In the middle came the whig Nottingham Herald, which lasted only three years and ceased in 1827, and the Mercury, a whig-liberal newspaper which was more successful, lasting until 1852.

Printed and published by Jonathan Dunn at premises in South Parade (formerly named Timber Hill,) the Mercury's principal owner was Thomas Wakefield, for many years the leading liberal in Nottingham, and one of its most powerful citizens. Twice mayor, Wakefield for a long time vigorously opposed enclosure of the common lands. Even when the main Inclosure Act of 1845 was passed, the paper (under Barker's successor) only grudgingly accepted the inevitable, chiefly on the grounds that there was an undeniable and pressing need for building land. The Mercury had little confidence in the success of enclosure, and was particularly unhappy that the Meadows would disappear.

Barker edited the paper for much of the time that enclosure was a burning issue in the town, and through its columns he of course reflected Wakefield’s anti-enclosure opinions. So it is interesting, though not surprising, that as 'A Wanderer' he stressed the beauty of the Meadows and of the Sand Field, which were to disappear under enclosure. His description of New Radford harked back to the country gardens that preceded enclosure there in 1797, while his only mention of the Sneinton enclosure was in connection with the destruction of the Shepherd's Race in the same year.

The Nottingham Mercury, while adopting a liberal stance, was not by any means as radical as its contemporary, the Nottingham Review. Although in favour of the Reform Bill, it held no brief for the Chartist movement. It may be added that, some years after Barker's departure from Nottingham, 'King Wakefield' went bankrupt as a result of imprudent investment in Thomas North's coal mines at Cinder Hill and Babbington, but bore his misfortunes with great dignity, and remained greatly respected in Nottingham.4

The author of Walks Round Nottingham: Matthew Henry Barker (1790-1846). From the printed collection of James Ward’s Nottinghamshire manuscripts.

The author of Walks Round Nottingham: Matthew Henry Barker (1790-1846). From the printed collection of James Ward’s Nottinghamshire manuscripts. The writer Spencer T. Hall was later to remember Barker vividly. Born at Sutton- in-Ashfield in 1812, Hall ran away from home and the life of a framework-knitter. Obtaining a job in the Nottingham Mercury offices, he of course encountered Barker: 'The first thoroughly literary man to give my young hand a friendly grasp was Capt. Matthew Henry Barker, author of'Greenwich Hospital,' 'Tough Yarns,' 'Jem Bunt,' and 'Walks round Nottingham, 'He was... a warm, florid, stiff-set, cheerful, heroic-looking man; could send jokes about him as thickly as a shot in action, and give a hearty laugh that might be heard for half-a- mile. Yet he would melt the eyes of his readers by his pathos when the season came, and was not by any means unacquainted with sorrow.'5

Hall had further recollections of Barker: 'There was the rosy, hearty, heroic 'Old Sailor,' Captain Matthew Henry Barker, the author of as many 'tough yarns' as might be twisted into sufficient cordage for a ninety- gun ship... and whose merry tide of laughter I can hear yet ebbing in the distance.'

Nottingham directories showed Barker living in 1832 in Clayton's Yard, off Bridlesmith Gate, and three years later in Carrington Street. He may have left Nottingham soon after ceasing to edit the Mercury, as he cannot be located anywhere in the 1841 census for the town. At all events, he was back in London by 1843, when Spencer T. Hall last saw Barker's 'rosy, sailor-like old face' on the occasion of his (Hall's) first public lecture in the capital.

We come now to 30 June 1846, and that day's issue of Barker's old newspaper, which had since 1841 again been titled Nottingham Mercury. In the summer of 1846, it was published twice weekly, and at half-price: a short and unsuccessful experiment. Tucked away quite inconspicuously in this paper was the following short notice: 'It is our painful duty to announce the death of M.H. Barker, Esq, formerly Editor of the Mercury, and well known in the literary world as 'The Old Sailor.' He had been indisposed for some time, but on Monday was taken worse, and died suddenly.' This notice was made all the more poignant by the presence, on the front page of the same paper, of a prominent advertisement for the newly published third edition of An Old Sailor's Jolly Boat.

Friends and acquaintances of Barker would have been sufficiently saddened by the mere fact of his death, but it is hard to imagine that anyone remained unmoved a week later after reading an item in the next- but-one Mercury, of 7 July. This was evidently written by someone who had known him very well professionally, and held him in great affection.

The writer outlined Barker's literary achievements before continuing as follows: 'He was a man of great energy of mind, highly susceptible, and his various productions were dashed off with a rapidity we have never seen equalled. He was the creature of impulse, and has many times given away his last shilling to those whom he believed to be objects of charity. Little did we think in announcing his death, that at the very time his eldest child and only daughter had hurried herself and infant into eternity. Happy was it that 'The Old Sailor' was spared the knowledge of so heart- rending a calamity. Perhaps but few families have been, as it were, so doomed to misery; after giving birth to one daughter (Mrs Norman) and four sons, Mr and Mrs Barker separated.

'We will here briefly state the fate of three of the children:- Henry, the eldest son, a fine young man, the very beau ideal of a young 'Middy,' after being several years in the merchant service, perished at sea. Thomas, the youngest, a good tempered, lively youth, was a midshipman on board an East Indiaman, and lost his life immediately on arriving at the end of his first voyage. Whilst lying at Calcutta, the vessel to which he belonged, took fire, and poor Tom, by over-exerting himself, took cold, the yellow fever seized him, and in twenty-four hours he was a corpse. William, the third son, an intelligent young man, who was for some time reporter on our establishment and afterwards on the Review - whilst visiting his father, in London, about twelve months ago, he was so broken down, both mentally and bodily, by disease, that he committed suicide, This was a fearful stroke to the father; he never overgot it, and wore gradually away, until, after being confined two days, death put an end to his sufferings. Robert, the second son, resided several years in Australia. He is a steady, industrious young man, and at present, we believe, employed in one of the dock-yards.

'Mrs Norman's marriage was a very imprudent one; her husband was well connected, had received a liberal education, but was of weak capacity; his friends, we believe, disowned him, and not being able to support his wife and family, no doubt formed bad connexions, and his high- spirited wife unable to bear up against her privations and misfortunes, her mind became affected, and suicide was the result. [Since the above was in type, we have been informed that Mrs Barker, whilst residing at Nottingham, gave birth to another daughter, who now resides with her mother, in London.]'

Even though the postscript brought the slightly more cheering news that Matthew Henry Barker was survived by two of his children, rather than only one, this is an appalling story. Tragedy is a word overused and cheapened nowadays, but Barker's life had surely been truly tragic. Further comment is almost superfluous. To have lost two children through sudden death, and a third through suicide, was terrible enough, but the final infanticide and suicide would have been enough to rob a parent of his (or her) sanity. Mrs Barker, who had to bear the shock of these last events, and of her estranged husband’s death, is equally deserving of sympathy in retrospect.

The extra title-page included in some copies of Walks Round Nottingham. The distant hill on the left of this view from Wilford Church appears to be Colwick Woods.

The extra title-page included in some copies of Walks Round Nottingham. The distant hill on the left of this view from Wilford Church appears to be Colwick Woods.All of this perhaps helps to make sense of the elegiac final paragraph of the main text of Walks Round Nottingham. Barker was 45 years old at the time of publication, but in this sombre passage conveyed the sadness and weariness of someone who has lived a long and melancholy life. "THE WANDERER' has thus far fulfilled his task, and he is now about to resign the pen with feelings it would be impossible to express. A few years at the utmost will pass away - it may only be a few days - and then the scenes of Time will close on him for ever.

He has endeavoured to snatch from oblivion a memorial or two of the silent dead, and he entertains some hope, that in after times his little book will do the same service for himself. Other busy feet will tread over the same paths that he has trod - the sky will be equally clear and bright - the fields and the meadows - the hills and the valleys - will continue to teem with the abundant supplies of a bountiful Providence, but the hand that writes - the heart that dictates - will be mouldering into dust. Oh may the living live as knowing they must die, and the thoughtless be taught to consider their latter end.'

Nearly 170 years after his walks round Nottingham brought Barker to Sneinton, it is pleasanter to picture this engaging, though troubled, man in happier mood as he strolled about the neighbourhood. He would, though, see little now in Sneinton that he would recognise. The site of Pennyfoot Stile is an ugly, soulless street; up the hill the church is quite dissimilar to the one he described; and the quaintness of the Hermitage has all but disappeared.

His book is well-worth seeking out, and deserves not be forgotten. Indeed, the fact that it gave rise to this article bears out Matthew Henry Barker's hope that Walks Round Nottingham might one day help to save his name from oblivion.

REFERENCES

1. The Hermitage remembered. Sneinton Magazine 15, Winter 1984/85

2. Francis C. Laird, Beauties of England and Wales, v. 12 pt. 1. London: printed for Sherwood, Neely & Jones. 1813 (See also Part 1 of this article.)

3. Gone, but not forgotten: Manvers Street Goods Station. Sneinton Magazine 3, Winter 1981/82

4. Derek Fraser, The Nottingham press 1800-1850. Transactions of the Thoroton Society v. 47, 1963. (This most lucid summary of the Nottingham newspaper history of the early 19th century deserves to be more widely known. I am glad to acknowledge my indebtedness to it.)

5. Biographical sketches of remarkable people. London: Simpkin, Marshall. 1873

I am grateful to Nottingham Local Studies Library for permission to reproduce the illustrations in both parts of this article.

< Previous