< Previous

PRECEDING THE CATACLYSM:

Sneinton and its parish magazine in the Edwardian era :

Part 1: Events great and small

By Stephen Best

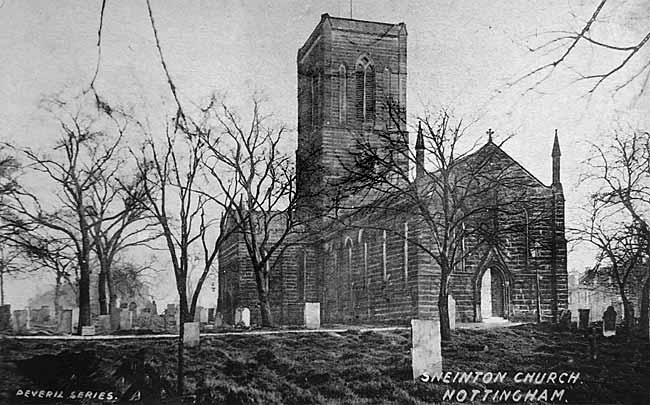

SNEINTON PARISH CHURCH from the north-west, c1904.

SNEINTON PARISH CHURCH from the north-west, c1904..... the word ‘Edwardian’, referring to a period of sunlit prosperity, and opulent confidence preceding the cataclysm of the ‘Great War’. (Oxford Companion to English Literature).

FOR ANYONE INTERESTED IN THE recent history of a locality, parish magazines are an invaluable source of information. They not only chronicle the minutiae of services and ecclesiastical news, but also provide frequent glimpses of contemporary attitudes and events, both local and national, in spheres other than the religious.

The parish magazine of St Stephen's is the best example we have in Sneinton of such a periodical, and the issues of its first year, 1869, formed the subject of an article in an earlier Sneinton Magazine.1 This is, of course, not to suggest that no other church or chapel was active locally; it is simply that their magazines or newsletters survive only in fragmentary form, if at all. Nor, in spite of the fact that we shall see Sneinton through the eyes of the parish magazine, must it be assumed that religious belief was necessarily a central pillar of every household.

The Sneinton Magazine before this featured an Edwardian photograph of Sneinton Road, sketching in some of the background to the world inhabited by the people pictured.2 From this, it was a natural step to look through the parish magazines spanning Edward VII's reign, to see what was being said locally about Sneinton and the wider world. One link was immediately apparent, some of the shopkeepers who figured in this previous article being regular advertisers in the magazine. In the following account, religious matters will not be ignored, but more attention will be devoted to secular affairs, and to the extra-mural activities of the parish church.

Although it ended only 89 years ago, the early part of the twentieth century leading up to the First World War is often considered to have been the closing phase of the old world. We shall see, however, whether an examination of Sneinton Parish Magazine from 1901 to 1910 entirely bears out this impression: The magazine dealt with enormously important issues and with trivial ones: it was in turn grave and light-hearted: it was capable of pomposity and of self- deprecating humour: and some of the writing in it was surprisingly good. We shall divide its contents into fairly well- defined areas. First, so as to set the other items in context, comes news of the parish church itself, then the magazine’s coverage of national and international events. Next are discussed items of significance to the city of Nottingham as a whole, followed by various questions and news items especially affecting Sneinton. We then look at sport and entertainment in Sneinton, and finally at the wonderfully diverting ways in which local people enjoyed a day away from home. If plenty of space is given to this last topic here, this merely reflects the degree of detail in which it was reported in the magazine. Our saga begins with the first year of the twentieth century, and of the King’s reign.

SNEINTON CHURCH AFFAIRS

Parish church matters were of course afforded ample coverage in the magazine. The Rev. Arthur Murray Dale, vicar of Sneinton since 1895, immediately struck a challenging note for the new century, referring in a rather tight-lipped way to the proposed St Christopher's mission church in Colwick Road, and making it clear that he took no responsibility for it or its kind of churchmanship.3 We are also made aware at the outset that Sneinton clergy of a century ago came from a different stratum of society from the one inhabited by most Sneinton people, and that relations between clergy and laity were not as easy-going as they might become later. The vicarage stall at the sale of work was conducted under the superintendency of the vicar's wife, the Hon. Mrs Dale; this lady was never referred to in the magazine with any lesser degree of formality, readers being regularly reminded that she was an 'Hon.'

January 1902 saw the vicar thank his readers for a 'handsome presentation.' This presaged his moving away from the parish. Having been offered another living, Mr Dale was about to leave Sneinton, but no announcement of this intention appeared in the magazine. Nor, for some months, would any mention of his remarkable successor be found in its pages.

The July magazine at last reported Dale's departure to become rector of Tingrith in Bedfordshire. Some officials of Nottingham Corporation may well have heaved sighs of relief on hearing that he had gone, for the vicar, had over the past few years been a thorn in their side. In addition to complaining that Sneinton streets were 'not properly watered or cleansed,' he had kept up a protracted campaign for the restoration of a horse-bus service to Sneinton. Though he had claimed to be acting on behalf of all local people, Mr Dale may have revealed his view of himself more accurately when he wrote that 'sufficient consideration is not paid to large ratepayers who have the misfortune to live in this district.' Dale was to remain at Tingrith until 1915, later becoming a Roman Catholic, as he had been briefly before coming to Sneinton.4

This same magazine included a letter from the incoming vicar, who would emphatically continue the association of Sneinton vicarage with blue blood. Thirty- nine years of age, the Rev. the Hon. Robert Macgill Dalrymple came from a curacy in Leeds. He was the youngest son of the 10th Earl of Stair, who had seats at two Scottish castles, and a town house in London. Although he had been ordained in 1889, and would live until 1938, Sneinton was to be the only parish of which Dalrymple had charge, from 1902 to 1917. Introducing himself to his new parishioners, Mr Dalrymple assured them that he was not altogether a stranger to Sneinton. He had lived for two years at Holme Pierrepont rectory before going up to Christ Church, Oxford, and also recalled happy memories of visits to Sneinton Manor House during the occupancy of Mrs Susan Davidson, noted local benefactor and donor of Sneinton Church Institute in Notintone Street. In his letter the new vicar promised to maintain the Sneinton High Church tradition.

One of the first complaints raised by him after taking over at Sneinton continues to provoke passions today: 'We wish that some means could be devised for keeping the dogs of the neighbourhood out of the churchyard. Apart from the general nuisance of the thing, it must be most disheartening and vexatious to those who endeavour to keep the graves of their relations nice, to find...the surface of the grave all scratched up and disfigured by these creatures.' He went on to say that the best answer would be for dog owners to control their pets more effectively, but concluded that this was probably a vain hope, and that other means might be necessary. These were not specified, and Sneinton churchyard still awaits a solution to the problem.

Among Church events of 1904 was a presentation to the organist and choirmaster, Charles Hole, on his completing 21 years in these posts. Hole, who was also head teacher at the Church Schools, received a silver tea and coffeee service and an illuminated address. After living in Sneinton Dale for many years he had recently moved house to West Bridgford. This was very much a sign of the times, as Sneinton (increasingly a workaday inner-city area of Nottingham) was losing several of its prominent residents to improving outer suburbs, or to surrounding villages easily accessible by rail.

News of alterations to the church fabric began to appear in 1905. The vicar reported in January that the reredos had been returned from London, where it had been altered under the supervision of the respected church architect Walter Tapper, who had also been involved in the erection of the rood beam and figures. Dalrymple looked forward to seeing Tapper's new organ case and gallery, the May magazine noting that this work was in hand, but that the congregation would for the time being 'have to put up with the church being in rather an untidy and dusty state.' By June the organ gallery was almost completed, and the writer hoped to see the disappearance of the scaffolding. The beauty and quality of the new work were highly praised. The organ was first used in September, and according to the October magazine sounded uncommonly fine.

THE REV. AND HON. ROBERT MACGILL DALRYMPLE (seated), with his curates, at the doorstep of Sneinton Vicarage.

THE REV. AND HON. ROBERT MACGILL DALRYMPLE (seated), with his curates, at the doorstep of Sneinton Vicarage.Writing in January 1906, the vicar stated that, in spite of improvements already carried out, much remained to be done to the building. A parochial party was to be held later in the month, at which he would tell members of the congregation how funds for further work might be raised. In the event much of the money came from the vicar's private fortune. Although he always forbore to mention it in his parish letters, the list of contributions revealed that out of £908 received towards the improvement scheme, no less than £350 had come from the pocket of the Rev. and Hon. Robert Dalrymple. This would be well over £20,000 at today's values. That plenty of cash was needed is evident from a remark in the April magazine concerning the church's heating system: 'It is certainly rather antiquated, as the present arrangement seems calculated to warm only that portion of the church just beneath the tower, while people sitting in the nave - at least the back part of it - and transept, have to sit through the services with chattering teeth, or at any rate cold shivers running down their backs.' Happily, October brought news of a likely solution to the heating problem. A Mr Musson, formerly a worshipper at St Stephen's, explained a scheme for the better heating of the building, at a likely cost of about £80.

November 1906 saw more venting of frustration over the perennial churchyard dog menace; 'Oh! those dogs, running and scampering over the graves in the churchyard as if the place belonged to them. Our hair grows grey as we watch their antics.' Readers were, however, warned that worse dogs were at work - two-legged ones who stole flowers from graves.

The vicar's incisive literary style was further exercised in May 1907 by the problem of confetti. 'Sometimes when the bride is engaged in signing the register bits of this miserable stuff keep on falling off the brim of her hat.' Not only this, but the parish clerk was groaning under the burden of sweeping it up: 'Poor Mr Gibson is rapidly getting grey in his efforts to keep the place tidy, and would we feel sure greatly appreciate a reduction of his labours in this direction.'

Mr Dalrymple, incidentally, was fortunate enough to be planning a summer holiday in Canada in 1907. He told his parishioners that he hoped to spend a few days with a cousin in Toronto, and to see Niagara Falls. The vicar had alarming news concerning this natural wonder: From all accounts it would be as well for intending visitors to the Falls to make up their minds to go there as soon as possible, as more water is being drawn off them year by year to supply the large town of Buffalo, and in course of time we fear that the Falls will be non-existent. Amost a century on, anxiety is still felt about the long-term future of Niagara Falls.

1908 saw a new oak pulpit in the church, replacing a stone one which, according to the March magazine, was 'certainly not what would be called an artistic gem.' Plans were also afoot for rebuilding the chancel under the architect C.G. Hare. The vicar wrote in May that, if these were carried through, 'We are convinced that we shall possess one of the most beautiful and stately chancels in Nottingham.' The magazine underlined the merits of the rebuilding plan by reprinting a description of the existing church when new in 1840, and gently scoffing at the perceived lack of taste which had led people to praise it at the time.

Mr Dalrymple announced in October that a faculty had been granted for the new chancel, and that the work would take about six months. He thought that little would be attempted before the spring, but in the event excellent progress was made in fine weather, and by the end of 1908 the chancel and vestry walls were well above ground. March 1909 described 'an army of masons' at work, with fresh stone constantly arriving from the quarry in Staffordshire. It had, said the vicar, been as good a winter for building as could be wished. Spring, though, proved fickle, and severe weather delayed the progress of the work. Its consecration, however, took place in September 1909, the magazine being especially impressed by the beauty of the new reredos.

May 1910 witnessed a large gathering at Sneinton Institute for the presentation to the vicar of an illuminated address and a Queen Anne chair, 'In recognition of his Work in Sneinton, and of his liberality, which made possible the building of the New Chancel.' In reply Dalrymple spoke about many aspects of his incumbency. Among these, he referred in rather defensive terms to the limited number of home visits he had made in the parish, pointing out that 'If he had not done all he ought in this respect he could plead as an excuse that it was not an exhilarating pastime in the neighbourhood. As a rule the dog was the only creature at home to greet one, but even if an occupant opened the door it was only to peep round the corner, and the clergy were seldom asked in and made welcome.' The vicar missed the warm-heartedness of Yorkshire people in this respect. Two songs performed by 'Miss Rose Fielman' were an added feature of the proceedings. Rose Feilmann (1877-1957) was daughter of a Nottingham lace manufacturer resident in The Park. Trained as a musician and singer, she would, as Rose Fyleman, become celebrated for her verses, including Fairies, which contains the well-remembered opening line: 'There are fairies at the bottom of our garden!'

In July came news of a special vestry meeting attended by C.G. Hare, who explained his plans for improving the remainder of the church in harmony with the new chancel. These would involve rebuilding of the nave, and construction of aisles and new transepts. It was decided that the vicar be asked to apply for a faculty for this work to be carried out. A further mention of the scheme came in September, when Dalrymple gave more details of what the new church would look like - an aisled nave without clerestory: the stained glass moved to windows in the new aisles: a large west window of plain glass: a much loftier interior than the existing one. Our final news of Sneinton church in the Edwardian age thus prefigures accurately what would be completed in 1912 and can still be seen by the visitor in 2003.

Sneinton at the beginning of the twentieth century.

NATIONAL ISSUES

From parish church intelligence we move on to matters of national importance noticed in the magazine. January 1901 had seen the vicar of Sneinton, A.M. Dale, mark the beginning of the twentieth century. In Nottingham, as elsewhere, 1900 had widely been properly recognized as the final year of the old century, rather than the start of the new one. This was in emphatic contrast to the celebrations greeting 1 January 2000 as the so-called opening of the 21st century.

The magazine soon had to report a happening of international significance, the February 1901 issue containing the vicar’s eulogy on Queen Victoria, who had died in January: 'Those of us who were privileged to see the funeral procession through London will never forget it. The crowd hushed and sad...the wailing of a trumpet from time to time...It was not only the passing of Victoria, it was also the burial of fragrant memories of bygone days.' Victoria had been on the throne since 1837, and even people in their seventies could not remember a time when she had not been their sovereign.

Following the old Queen's death, the great national event of 1902 was naturally enough the Coronation of Edward VII. The July magazine, however, had grave news to report. This was the postponement of the ceremony, on account of the King’s operation for acute appendicitis. Following a note in August that His Majesty was not yet sufficiently well to stand up to the strain of the Coronation, the September magazine confirmed, with relief, that Edward's Coronation had at last taken place, and that the King had apparently come through it well.

June 1902 had seen another momentous occasion. With the declaration of the end of the South African War, Sneinton, like many other places, held a parish thanksgiving service to mark the peace. In the light of South Africa's subsequent history it is interesting to read that the vicar told his congregation that: 'As the Boers were now part of the British Empire, all feelings of bitterness must now be put away, and we must be ready to welcome them as brothers in the great nation to which we and they belong.'

What some considered a grave threat to the country was raised in the August 1904 magazine. Here the vicar referred to the national annual festival dinner of the Church Lads' Brigade, and in strongly supporting its work, quoted with approval the views of the Duke of Portland, its chairman, on the youth of the country. This Nottinghamshire nobleman had asserted that: 'There are thousands of young men in our towns - and country districts too - who take no thought of, and do nothing to ensure their bodily health and strength. Look at them in the streets on any holiday, or on Sunday evenings; they lounge through life, bad in manners, bad in physique, ill grown, sloping in the shoulders, slovenly in walk, and without a trace of manly self-respect. They possibly constitute a danger to the British race.' The capacity of the old for criticising the young seems to have changed little over the intervening century. Indeed, although the Duke was probably unaware of it, Plato had been saying much the same thing about the youth of Athens in the 4th Century BC.

The February 1906 magazine dipped a toe in the dangerous waters of party politics, observing that, 'Through the defeat of Lord Henry Bentinck and Mr Bond at the polls, we have lost, as our representatives in Parliament, two very excellent and upright gentlemen.' Lord Henry was half-brother to the Duke of Portland, and like Edward Bond, had sat as a Conservative for a Nottingham seat since 1895. The return of a Liberal government with a huge majority foreshadowed, in the view of many churchmen, disestablishment of the Church in Wales, and a new Education Act which would change control of Church Schools.

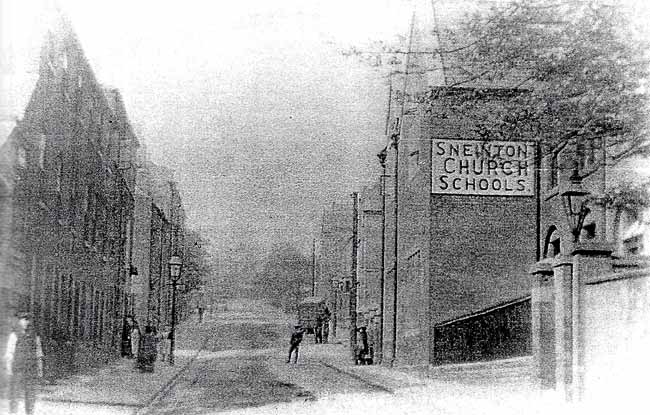

The vicar of Sneinton fully shared these fears, the May issue including a long diatribe against a 'glaringly unjust' Education Bill, which proposed to hand over nearly all Church of England schools to local authorities, with consequently reduced opportunities for religious instruction. Dalrymple was confident that this bill would have to be considerably amended, if not withdrawn altogether. It was, of course, the threat posed to Sneinton Church Schools which prompted the magazine to give the matter such prominence. For several years this national controversy with a local focus would trouble its pages. It was a pity that, while furiously attacking this projected aspect of education reform, Sneinton Parish Magazine quite failed to commend other great steps taken by this Liberal government, such as the introduction of free school meals for poor children, and medical examinations for elementary school pupils.

Demonstrating the rancour engendered in Nottingham by the bill, the June 1906 number included a long report of a meeting of local churchmen at the Mechanics' Hall to protest against what they held to be, among other things, the onset of secularism and ' a violation of all principles of public morality.' A thinly attended meeting on this vexed subject was held at Sneinton Institute, and reported in July. In a fervent speech Mr William Henry Mason (of Newball & Mason, botanic herbalists of New Basford) claimed that Undenominationalism was not Christian, and would be as acceptable to a Mohammedan or a Unitarian. A second speaker criticised the education record of another body of Christians: 'The enthusiasm which Nonconformists professed for education had been to look on while Churchmen had spent £50 million pounds in providing education and religious instruction for poor children, who otherwise would have had none.' The Education Bill was again referred to in the May 1907 magazine, the vicar still doubting that it would be passed into law as it stood. When the Bill was indeed withdrawn, Sneinton Parish Magazine expressed great satisfaction and thanked all who had opposed it.

May 1907, however, saw a new Education Bill come under discussion. The Government minister concerned believed that it would 'Meet the particular difficulty of those who feel themselves prevented by their consciences from paying rates in support of denominational instruction of which they disapprove.' Its opponents asserted that it would also deprive denominational schools of a proportion of the Parliamentary grants earned by them, and that the deficiency would have to be recovered from their managers.

WINDMILL LANE and SNEINTON CHURCH SCHOOLS, about 1907.

Nothing more was heard for some months, but in December 1907 the vigilant Mr Dalrymple was again warning against this 'new and drastic' Education Bill, which would prohibit definite religious instruction in all schools during school hours. This, thundered the vicar, would have to be vigorously resisted, as its predecessor had been. February 1908 duly reported the founding of the Parents' League, a nationwide organisation upholding the parental right to decide what kind of religious education their children would receive, and of knowing that the teacher concerned believed in the religion he or she taught.

The following month found the bill before the Commons. Church Schools would be contracted out, as they had been before 1902, but in the light of the decline in voluntary subscriptions, and the building improvements which would be forced on them by government, the vicar believed that almost all church schools in single school areas would become extinct. The controversy raged on into December, with Dalrymple hopeful, as before, that the government would have to think again on this emotive issue.

The magazine continued to give prominence to this question: in his New Year letter for 1910 the vicar pointed out the imminence of a General Election, and as our final comment on this ongoing debate urged Church people to vote only for candidates who supported equal treatment in religious education - Church teaching for Church children, Nonconformists to teach Nonconformist children, Jewish teaching for Jewish teaching, and so on.

Dalrymple and those who shared his views prevailed, with three successive Liberal ministers failing to get their suggested changes in religious education on to the Statute Book. The long-expected disestablishment of the Church in Wales did eventually occur, but not until 1920.

A quite different Act of Parliament had also greatly dismayed Mr Dalrymple, who wrote in October 1907 to deplore the passing into law of the Deceased Wife's Sister Bill. This, after years of wrangling at Westminster, at last made it possible for a widower to marry his sister-in-law. The vicar observed that the act did not oblige Church of England clergy to officiate at such a marriage, or to lend his church for the purpose: 'Otherwise a somewhat unpleasant situation would have been created.' He suggested that people in this position should marry at a register office.

An event of worldwide importance in June 1910 found Dalrymple writing in terms similar to those employed by his predecessor Mr Dale, nine years earlier. King Edward VII was dead. First news of his illness had been received early on 6 May, and he died before noon on the same day. The vicar wrote: 'The prevailing note or mark of the King's life was devotion to duty... he exhibited on all occasions a personal charm of presence, a kindliness and joyousness of heart, and an unerring tactfulness which has endeared him...to all his loyal subjects.' A nine-year reign must have seemed terribly short to those who had lived through most of Victoria’s 63 years as queen.

NOTTINGHAM NEWS AND TOPICS

Moving from matters of nationwide concern, we now see what Sneinton Parish Magazine made of news and issues which particularly affected the City of Nottingham. June 1901, for example, referred to the new electric trams, which had come into service on New Year's Day. They would not reach Sneinton for several years yet, but got into the magazine when the Sneinton Boys' Brigade Company, having taken part in a march to Daybrook, stoutly marched back as far as Sherwood, 'Where we took the electric car.' We may feel that the lads thoroughly deserved their ride after their traipse of six miles. Similar feats of physical fortitude will be revealed as we go through the parish magazine over the next few years, all of them cheerfully undertaken by local people out for a day’s enjoyment.

In March 1903 Sneinton residents were invited to attend a lecture at Circus Street Hall, open to all Nottingham citizens, and illustrated by the infant Kinematograph. Its subject was 'Housing of the Poor,' which the magazine properly considered 'a question so vitally important to the well-being of the whole community.' The Lord of the Manor, Earl Manvers, would be in the chair. One is glad, a hundred years on, to observe that Lord Manvers took an interest in this burning issue, and hopes that the meeting was not publicised in the Parish Magazine simply because he was patron of the living.

The January 1906 magazine reflected the British obsession with the weather, recalling that 1905 had ended in Nottingham in what seemed more like early spring than mid-winter. Although the traditional White Christmas had been missed, 'It was a comfort this year to be free from the fog fiend.' Just a year later, however, it was noted that Nottingham was at last in the grip of a 'good, old-fashioned winter.' Perpetuating Mr Dale's Sneinton custom of criticising the local authority, the magazine chuntered on about the lack of attention paid to the streets during the severe weather. 'As we write, the snow has now been on the ground for four days, and the corporation of Nottingham has made no attempt to clear it away. It is now in a most filthy condition, and...we have to wade through a perfect quagmire of slush in the streets. Surely some attempt might have been made to clear the main streets, like Sneinton Road. We hear a good deal now-a- days about the unemployed from time to time, and we wonder what has become of them all.'

It may be felt that, while the council were fair game, the little dig at the unemployed sat rather unhappily in a church magazine. The magazine continued to be absorbed by the weather from time to time, later issues lamenting the wet and sunless summer ot 1907, and the icy-cold Easter weekend of 1908.

One of Nottingham’s most cherished institutions came under the vicar's scrutiny in October 1907. 'Goose Fair again. We live in an age when many things move very rapidly indeed! Great revolutionary changes are in the air, such as the nationalisation of the railways and the land, when we suppose that the unfortunate landowners will have to flee the country or submit to some other interesting process of extinction, but Goose Fair still holds the field, still occupies year after year its position in the most important part of Nottingham, and seems likely to continue to do so. We will not do Goose Fair the injustice of calling it a relic of barbarism, but we do think that it is about time, from a sanitary point of view, as well as from other consideration, that the Fair should be removed to some place on the outskirts of the city.' Revolutionary changes: the terrors of nationalisation: unfortunate landowners. As we shall have reason to notice again, Mr Dalrymple's noble lineage sometimes rose irresistibly to the surface in his parish magazine utterances.

In his January 1909 message the vicar touched on the current trade recession in Nottingham. Acknowledging the anxiety it had brought to many families, he hoped that the coming year would see a sustained revival. A year later he again looked forward to a marked improvement in the trade of Nottingham and the country generally, recognising that unemployment meant widespread 'bitter suffering and privation.'

SNEINTON LOCAL NEWS

In addition to topics of interest to Nottingham as a whole, the magazine naturally reviewed issues of specific concern to Sneinton. Much of this was more parish pump material than headline news, but some people in June 1902, for instance, were doubtless glad to read that the church bath chair was now available to rent by the hour or day from the parish clerk. A precursor of Shopmobility, perhaps?

February 1903 brought to light an unlikely state of affairs, with the Church Institute reporting a lack of demand for its card room and billiard tables. This unaccountable disinclination to while away an evening in unimproving pleasure must have been a rare aberration in Sneinton. All was clearly not well at the Institute, as in August an appeal was published for funds towards its repair and redecoration. About £80 was needed, the writer of the appeal reminding readers that 'our highly-esteemed late Parishioner, Mrs Davidson,' once of Sneinton Manor House, had given £3,000 for its construction in 1880. (Mrs Davidson, it will be remembered, had entertained the young Robert Macgill Dalrymple during his stay at Holme Pierrepont.) In the event, the Institute, at the corner of Notintone Street and Beaumont Street, continued to give valuable service to the community until its destruction by fire in the 1960s.

The Sneinton Church School authorities expressed resentment in 1903 of a Board of Education ruling. This stipulated that two representatives of the City Education Committee must join the four foundation managers, to form the management committee of the Schools. Herbert Grundy, financial secretary to the managers, argued that the existing system had saved ratepayers large amounts of money, and that changes in the management system were to be deplored. In a postscript, however, he reported that the two City representatives were to be the Rev. Speight Auty and Alderman Pullman, and conceded that the assistance of these highly respected local men would be warmly welcomed.

Indeed, no two better citizens could have been chosen. Speight Auty had been minister of the Albion Congregational Church in Sneinton Road since 1894, restoring its influence in the community after accepting the pastorate at a time when the Albion was at a very low ebb.5 Frederick Pullman was a leading local businessman, and a remarkably enlightened employer for his time. His extensive draper's shop in Sneinton Street (now Lower Parliament Street) is still remembered by older people in Sneinton and further afield. More will be said about Pullman in due course.6

1903 was a very busy year at the Church Schools. During the summer holidays the accommodation of the Infants' Department had to be reduced from 311 to 271, in the interests of 'the comfort and health of the children.' This drop in numbers was necessitated by the conversion of a classroom into a cloakroom, and removal of some of the old-fashioned galleries. Financial constraints, however, meant that the provision of a greatly-needed new lavatory had to be deferred.

The September 1906 magazine greeted the impending arrival in Sneinton of an overdue amenity. 'At last the long talked about tramway along Bath Street, Manvers Street and Colwick Road is being laid, which will no doubt prove a great boon to residents in the neighbourhood, though we must admit to a feeling of extreme satisfaction that the City authorities have not selected Sneinton Road as the channel of their experiment. In the first place, if this route had been chosen, it might have been, indeed very probably would have been, found necessary to cut a piece off the Vicarage garden, and cut down the beautiful ash tree in the corner overlooking the road, and secondly, the incessant noise would surely have been very trying in such close proximity to the church, as well as, at any rate, to some of the residents in this important neighbourhood. No, the advantages of the Colwick Road route are obvious; for not only has it been found necessary to pull down a considerable area of slum property in that truly most depressing neighbourhood called Manvers Street, but there is also the additional advantage for the trams of a route without gradients.'

This item provides considerable food for thought. First, one can imagine how pleased Nottingham Corporation officials must have felt on receiving words of approval from Sneinton vicarage, after all the criticism over buses, street cleaning, and snow clearance, with which Mr Dalrymple and his predecessor had bombarded them. It is odd, though, that the vicar should have considered the Sneinton tram route an experiment, more than five years after the electric trams had proved successful in Nottingham. Nor can he be acquitted of what we now call nimbyism - on this occasion more a case of 'not in my front garden,' than 'not in my back yard.' Yes, the trams would have made a noise grinding up Sneinton Road, but the vicar here cheerfully ignored the fact that they would also make a noise passing St Christopher's church in Colwick Road. As we saw in 1901, however, relations between the two churches appeared less than fraternal in those remote days.

Everyone would have been glad that the vicarage garden and trees were saved, but the mention of 'some of the residents of this important neighbourhood' was unhappily reminiscent of Mr Dale's earlier pleading on behalf of 'large ratepayers who have the misfortune to live in Sneinton.' It might also have been tactful not to have ruffled the feathers of Manvers Street residents so roughly. Many who still lived there must, after all, have been decent and self- respecting people. This was another of the times when Mr Dalrymple's common touch appeared to desert him in print.

Nor was it any more evident in a paragraph in the October magazine, which commented on the extensive new building works going on in the Sneinton Dale and Sneinton Boulevard areas. We feel tempted to ask why and wherefore. There does not seem, as far as we can gather, to be any real need for increased house accommodation, as we are told there are hundreds of houses in Nottingham untenanted.' Had the vicar looked more closely at some of the dreadful houses in the Carter Gate and Manvers Street area, he would have been able to understand why many were empty, and why wholesome new homes were sorely needed. Indeed, only a month earlier he had been applauding the demolition of slum properties in Manvers Street. Some illogical thinking is surely apparent here.

In February 1907 appeared further interesting thoughts prompted by the construction of the Sneinton tram route. Noting that it would not be long before electric trams ran through the neighbourhood, the magazine commented: 'Their proximity to Sneinton Church suggests to us the possibility of obtaining electric light for the Church. The initial expense might be somewhat heavy, but what an unspeakable gain and blessing it would be to get rid forever of the abominable fumes which are inseparably connected with incandescent gas.' Whatever the practical difficulties of supplying electricity from the tram supply, the vicar (surely it cannot have been anyone else?) was shrewd enough to recognize that electric light was the thing for the future: cooler, infinitely more pleasant than gas, and much more easily 'manipulated.'

1. A church's year. Sneinton Magazine 74-75, Spring- Summer 2000

2. Edwardian afternoon. Sneinton Magazine 85, Winter 2002/3

3. For a fuller account see Mission accomplished Sneinton Magazine 49, Winter 1992/3

4. This was alleged in a supplement to The English Churchman for 30 September 1897

5. More about Speight Auty can be found in The poet and the pastor. Sneinton Magazine 79, Summer 2001

6. A fuller account of Pullman appears in Picturesque and worthy of inspection: Sneinton echoes in the Church Cemetery, Nottingham. Sneinton Magazine 72, Winter 1999/2000

(Part Two will record the deaths of three notable local people, before turning to the lighter side of Sneinton Parish Magazine from 1901 to 1910. This involves sport and entertainment, and the extraordinary variety of outings undertaken by Sneinton residents.)

The newly opened SNEINTON TRAM TERMINUS Colwick Road, 1908.

< Previous