< Previous

PRECEDING THE CATACLYSM:

Sneinton and its parish magazine in the Edwardian era :

Part 2: Chiefly pleasure

By Stephen Best

SNEINTON MANOR HOUSE in its latter days, when Mrs Susan Davidson and her husband were tenants.

SNEINTON MANOR HOUSE in its latter days, when Mrs Susan Davidson and her husband were tenants.... the word ‘Edwardian’ referring to a period of sunlit prosperity, and opulent confidence preceding the cataclysm of the 'Great War ’. (Oxford Companion to English Literature).

(Part One related how Sneinton Parish Magazine in the years 1901-1910 dealt with Church matters, national and international issues, and general news concerning Sneinton and Nottingham. Part Two begins with three prominent local people, before turning to the leisure activities of Edwardian Sneinton.)

LOCAL PERSONALITIES

MAJOR-GENERAL VALENTINE STORY, from a drawing in the ’Nottingham Daily Guardian,’ 1906.

MAJOR-GENERAL VALENTINE STORY, from a drawing in the ’Nottingham Daily Guardian,’ 1906.FROM TIME TO TIME THE PARISH magazine reported news of retirement, departure from Sneinton, or death of someone well-known in the local community. The deaths of two especially worthy men were chronicled during 1906. In May a short notice announced the passing of Major General Valentine Story, at the age of 88 'at his residence in the Forest.' Over the years many people have wondered who the General was, after reading his name in a stained-glass memorial window in Sneinton church. This commemorates his daughter Meina Story, who died in 1887. She, with other members of her family, was a benefactor of the church, and a devoted worker for its various organisations.

Major General Story, who lived in Forest Grove, off Mount Hooton Road, was born in 1818 at Woodborough Hall. Obtaining a commission in the Army in 1835, he served in, among other places, Canada and Ireland. In 1851 he was appointed staff officer for

Army pensioners in Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, a post he held until his retirement. Active in the early days of the Robin Hood Rifles, he took temporary command for their first parade in 1859. He was also involved in quelling the Nottingham election riots of 1865. An antiquarian and numismatist, Valentine Story was a keen supporter of Nottinghamshire County Cricket Club, for whom one of his sons played several times. A staunch Tory, he was a regular worshipper, not at Sneinton, but at St Mary's church. A sketch of him in the Nottingham Daily Guardian on the day following his death showed a typically Victorian officer, sporting luxuriant white moustache and whiskers.

(His son just referred to, incidentally, enjoyed a remarkably varied life. Col. William Frederick Story, who died in 1939, was at various times soldier, cricketer, rider to hounds, inspector of weights and measures, senior police officer, and racehorse owner.)

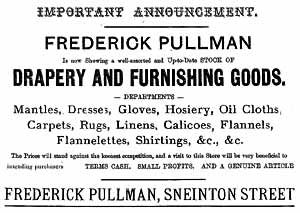

October brought news of the death from pernicious anaemia of someone already met in Part One in connection with the Church Schools. Alderman Frederick Pullman of Castle Street was born in Devon in 1838. He came to Nottingham as a young man, opening his drapery shop in 1859. An ardent Liberal, he played a leading role in municipal affairs, being elected both sheriff and mayor of Nottingham. His emporium, which eventually grew to fill almost the entire block between Gedling Street and Southwell Road, closed in the 1960s. Pullman was, as previously noted, a caring employer, being an original promoter of the Nottingham Thursday Half-Holiday Association for shop workers. Like General Story, he was a regular attender at St Mary's. He is remembered by Pullman Road, which links Sneinton Dale with Thurgarton Street. The magazine observed that : 'We have lost in this parish, through his death, a generous and warm-hearted friend, and one whose loss will be felt, not only in the particular district in which he lived, but through the whole of Nottingham.' 1

A PULLMAN’S advertisement from the December 1901 Magazine.

A PULLMAN’S advertisement from the December 1901 Magazine.November 1906 reported an accident which had befallen a third distinguished personage. This was Mrs Susan Davidson, who had left Sneinton not long before the demolition in 1894 of the Manor House, her home for many years. She was by 1906 resident in London and Scotland, and while being driven in her brougham in London was involved in a collision with a horse- drawn van, whose shaft struck the poor old lady in the face, fracturing her jaw. Unhappily, she never really recovered from this mishap, and died late in 1912. Born in Scotland, like her husband, Mrs Davidson had been a pillar of Sneinton church, a Sunday School teacher and district visitor. She tended, perhaps, to assume the air of a traditional lady of the manor, and became affectionately known locally as 'Lady Davidson.' She was always careful to look after the welfare of her former household employees, and the story was told of one these, an old woman who approached her after Church with the request: 'Please, my lady, could you make it gin next time?'2

INDOOR ENTERTAINMENTS

We now turn our attention to the Edwardian leisure activities chronicled in Sneinton Parish Magazine. Among these we cannot, of course, expect to find anything that was not respectable. No mentions of public houses sully these pages, and one looks in vain for any account of the artistes who delighted audiences at the Empire or the Theatre Royal. Sneinton people nonetheless enjoyed modest evenings out on their own doorsteps. We learn, for instance, that the Girl’s Club were rehearsing what was described as a 'charming Cantata'. Beguilingly entitled 'Madam Muddle's Dream.' it was to be staged at Easter 1902. Parents of the performers no doubt made a note in their diaries, but few others can have done so, as a writer in the May magazine was 'sorry that the girls had not more encouragement in a larger audience. ’

One obviously blameless entertainment was given in January 1906 at the Church Institute in Notintone Street by the wonderfully-named Mr Oldbury Brough. The January magazine quoted the Bishop of London's opinion that: 'There was nothing in the entertainment which could offend good taste,' and the following issue was glad to confirm that Brough had indeed been a great success, his 'suburban soiree' and 'peculiar pianoforte productions' being first-class. 'The fact of one man being able to keep his audience interested and amused through his own individual efforts for the best part of two hours is in itself a proof of the excellence of his capabilities as an entertainer.' Although it is hard in 2003 to imagine what on earth his act was like, one is glad that Mr Brough brought the house down.

In April it was announced that 'The Taming of the Shrew' would be performed in the Institute, in aid of the Church Improvement Fund. One wonders whether someone considered this play a trifle daring for some members of a Sneinton Church audience in 1906, as the magazine suggested that: 'Those of our readers who are in possession of the works of Shakespeare would do well to read over the play before attending the performance.' The Theatre Royal had offered to lend the appropriate scenery, thus keeping expenses to a minimum. The June magazine included a brief notice of the performance, showing a fine ability to damn with faint praise: ' They gave a very creditable performance, though of course it would not be fair to compare it with that of professional actors.'

In January 1908 Sneinton Institute was the scene of another ultra-respectable entertainment, provided by the exoticsounding Zelo. This performer, son of a clergyman in Kent, was 'quite a young man,' whose act consisted of shadowgraphy, paper folding and conjuring. 'An inadequate lantern' marred the first of these, but the remainder of his performance was 'very clever, and elicited great applause.' Zelo was hoping to earn a living by his act, but this description of it does not fire the imagination, and it is hard to believe that he ever reached the heights as an artiste.

FOOTBALL AND CRICKET

By no means biased towards genteel indoor amusements, the magazine also gave generous space to outdoor sports, and in November 1902 brought up the important topic of football. The Day School had taken on St Mark's in a match, 'Which, unfortunately, they did not win, though during the first half they had all the best of the game.' One can only admire this delicate way of reporting a defeat, with the suggestion that the Sneintonites had at least won one half of the match. There will, as we shall see, be further examples of this brand of reportage. (St Mark’s church, incidentally, stood in Huntingdon Street, close to where Hopewell's furnishers now are.) On a more upbeat note, Sneinton YMCA were able to report in the December magazine that, playing at Colwick Road, they had won seven out of nine games.

By 1903, St Stephen's Football Club were renting a field in Colwick Road, and had achieved ten wins in twelve games. Unfortunately, a match against Bridgford Rovers, as reported in January, wrote a further chapter in the bad luck saga. 'We do not attempt to excuse ourselves for this match; but to our sympathisers let it be known that nor one of us had had any practice, and, being out of form, could not endure the great heat as well as our opponents.' Great heat, in a Sneinton football season? Can global warming be such a recent phenomenon after all? April brought the account of an away match in which the Church School footballers took on Stanley Road Board School (my old school in Forest Fields, by the way.) Sneinton lost, but there were, needless to say, good reasons. Not only was an obvious penalty not given, but also 'The pitch was rather of the switchback order, and much bigger than the Sneinton boys' field... Stanley Road were a much bigger built lot, and the ground was familiar to them...' We Wuz Robbed again.

Sneinton sporting activity was evidently at a low ebb during the summer of 1906, the August magazine printing an apologia for the dilatory doings of the parish Cricket Club. 'What with opponents not turning up, or when they did turn up, proving to be much above the average age of our team... what with our own team arriving on the ground shorthanded, and retiring, alas! defeated: the season has not so far been brilliant.' In a heartfelt outburst the writer echoed the feelings of every club secretary over the years in asking why the running of a parish cricket or football club was so difficult, and why there was not a ceaseless flow of young men anxious to play. He went on to draw wider conclusions: 'But we English people are so fearfully devoid of esprit de corps (otherwise we should surely vote for conscription, or universal military service, to-morrow.')

He went on to lament the rise in professional sport, the willingness of too many merely to watch, rather than play, and to bet on sporting events, and further observed that too many teams of various kinds had little real connection with the Churches or organisations whose name they bore. Sneinton, he affirmed, would not go down this road. As if to acknowledge that these comments verged on the controversial, the piece ended: 'The writer of these notes wishes it to be understood that the editor of this magazine is on the high seas, and therefore is in no sense responsible for the opinions of his deputy.' Who was this deputy? My money is on the vicar, as it is difficult to believe that anyone else in the parish would have made such an authoritative pronouncement.

Further evidence of devotion to cricket appeared in the June 1907 magazine, which congratulated Nottinghamshire on a splendid start to the County Cricket season, and hoped that they would end up as champions, in September the writer was indeed able to congratulate Notts on achieving this distinction, quoting what the Nottingham Guardian and the Yorkshire Post had said of their achievement. Not only this, but the October magazine described a ceremony at the Mechanics' Hall, when presentations were made to members of the triumphant Nottinghamshire team.

Even when the Sneinton Church cricket and football teams did well, as in 1908, they suffered from a marked lack of support, and the December magazine tried to drum up some fans, emphasising the importance of 'the presence of sympathetic spectators.' This plea evidently fell on deaf ears, as, in spite of a record of five wins in seven matches, the November 1909 issue found it necessary to remind wellwishers that the team played their home matches in Meadow Lane, close to the Midland Railway level crossing.

Further indication of the difficulties under which the footballers laboured came in March 1910. Their low lying pitch in Meadow Lane had been 'once entirely, and on a subsequent occasion entirely, converted by floods into an inland sea. ' In spite of all these vicissitudes, the club had been very successful, the June magazine describing their past season as a 'brilliant success.' With a record of 22 wins in 28 matches, and 104 goals scored and only 33 conceded, this was fair comment.

DAYS OUT FROM SNEINTON

It has already been mentioned in passing that a degree of physical fortitude must have been necessary for participation in some Sneinton activities. Nothing exemplified this better than the extraordinary pains taken by local people in simply getting away for the day. Luckily for us, participants in these trips were only too willing to record their outings: voicing praise or criticism as appropriate, owning up to embarrassments and disappointments, and indulging occasionally in gentle selfparody.

The 1901 choirmen's outing in July, for instance, took the form of a day out to Llandudno, which, remarkably, also involved a steamship excursion to the Menai Strait. It comes as no surprise to read that the 30 stalwarts who made this trip were obliged to catch their outward train at 4.30 a.m. Accounts of similarly punishing excursions enliven the pages of the magazine in ensuing years.

In July 1902 the magazine related how the Sunday School teachers had embarked on a trip to Hazleford, leaving Sneinton in a large horse-brake. On arrival they crossed the Trent by the ferry, climbing up a steep bank on its south side; from here they could see the towers of Southwell, the spire of Newark, and, rather surprisingly, 'the noble chimneys on Carlton Hill.' - we must assume that the brickworks caught the writer's aesthetic eye. 'Descending through the woods to the river bank we then, and only then, found out that we had been trespassing, and were liable to all sorts of condign penalties. We recrossed the river as hurriedly as circumstances would permit, and arrived in good time to take our places in the brake. We arrived home safely, (I will not say without casualties) at about 10.30...' It is nowhere stated, but one infers that this most respectable party was warned off by a landowner, keeper, or water bailiff.

Of greater interest to Sneinton children would have been the summer treats for the Sunday Schools, reported in August. The seniors, 270 of them, accompanied by 50 adults, trooped down to the Midland Station to take the train to Plum tree, where they 'set to work to amuse themselves' on a farm. After tea the party left for the station, 'which the majority of us left by the 8.40 train, a few of us preferring to walk home.' Reading this throwaway evidence of muscular Christianity, and reflecting on the decision to walk the five or six miles from Plumtree to Sneinton in the late evening after an exhausting day, one cannot help feeling that it was their own fault that 'many, perhaps, found the next day hardly sufficient to recover in.' The infants, meanwhile were taken nowhere more exciting than the school yard in Windmill Lane, for games and sticky buns. One trusts that they were suitably resentful.

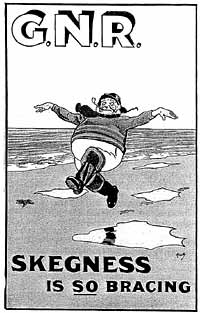

THE SKEGNESS POSTER which Sneinton excursionists would have first seen at Nottingham Victoria Station in 1908.

THE SKEGNESS POSTER which Sneinton excursionists would have first seen at Nottingham Victoria Station in 1908.The choirmen settled for what they hoped would be a less arduous day out than the previous year's. Early in September they went from Victoria Station to Stratford-on- Avon, whose delights they savoured before travelling the eight miles on to Warwick by horse-drawn brake. There they were dismayed to find that the Castle could not be visited as Coronation festivities were being held there. (Some poor intelligence work is apparent.) A week later the choirboys took the train to Skegness, where, as related in the October magazine, a cricket match took place on the sands, the ball frequently ending in the sea. Others patronised the switchback railway or the donkey rides. The writer concluded: 'We certainly think that Skegness is excellently adapted for a trip of this nature, and can well understand its popularity with the boys.'

Lest any reader in 2003 consider this enthusiasm excessive for a day in Skeggy, it ought to be remembered that some of the lads had in all probability never seen the sea before, and that those who had would very likely not get another glimpse of it for another twelve months.

Although having frequently to set out and return at an unearthly hour, our Edwardian forebears did at least enjoy the use of the British railway network at its high noon, with many places accessible by train which have now long been bereft of all rail communication, or at any rate, of a reasonable route from Nottingham.3 Those who made shorter excursions by road a hundred years ago should not, however, be underestimated. Many of our local country roads were then little better than dirt tracks, and as late as 1912 weeds sprouted luxuriantly along the Great North Road.

Numerous outings were reported in 1903, so a few highlights must suffice. The choir excursion in July was to Scarborough, the trippers leaving Nottingham by the Great Northern Railway before 6 a.m., and not getting back until 1.30 next morning. 'Were we disappointed in the trust which we so implicitly reposed in the G.N.R. ? Who could for one moment say so? The speed attained, it is true was not exactly of a racing description, 154 miles in 5 hours is sure and steady, but not swift...' We detect here someone with a sharp eye for the foibles of railway companies, and a nicely sarcastic turn of phrase; the Great Northern would not be the only line to draw his fire.

The mothers' meeting picnic was held at Costock, the intrepid ladies journeying by horse brake. With praiseworthy candour, one unnamed member of the party wrote in the August magazine: 'We took a great deal of packing in, for some of us were very large, the great difficulty was to struggle up on to the box seat.' The vicar, displaying commendable keenness and fitness, cycled the nine-miles to Costock to join them. An outing of the vicar's class to Oxton in the same month, by the way, was not without mishap: 'Some of the party got left at Burton Joyce, but all returned safely by train. ’

The 1903 Sunday School treat took place in the not very exotic location of Colwick Road cricket field. The September magazine described how, just as the band was due to play, the rain started, and everyone had to find their way home in the wet as best they could. The report contained one curious allusion to Plumtree, venue for the previous year's outing: 'After all is said and done, Sneinton is a far better place for such entertainments than Plumtre [sic]. Although we are free to admit that the latter name has an alluring title - which, however, suggests charms which it does not in reality possess, at any rate not in the month of July.' What on earth can this be about, and what had Plumtree done to cast such a long shadow?

Outings continued to figure so frequently in the magazine that one is tempted to picture Sneinton as a sort of Edwardian transport terminal, dispatching and receiving pleasure-goers in a continuous stream. In 1904 members of the Mothers' Union encountered setbacks on an expedition to Newstead, as related in August. They arrived 'at the Newstead Abbey Park gates, through which we peered with longing eyes, but were not allowed to enter. We understand that the grounds at one time used to be open pretty frequently to the public, but in consequence of the abuse of this privilege by some, entry to the grounds has now been restricted to two days in the week, and then only to parties of seven at a time.'

Someone had clearly been breaking the rules at Newstead, to the detriment of the unlucky Sneinton ladies. Once more we are made aware that there never was a golden age, in which everyone knew their place, behaved themselves, and observed the rules. Rose-tinted spectacles have often given a false picture of the past.

We may, I think, assume that this Newstead report was written by the lady who described the Costock trip in 1903, as the ample proportions of some of the participants are again hinted at. Unable to get into the Abbey grounds, the excursioners repaired to The Hut tea gardens across the road, 'Where there are some most attractive swings ... .calculated to bear the strain of almost any weight.' This correspondent was determined to make the best of the day, even relishing an incident on a homeward journey of more than two hours, when: 'We rather think they enjoyed their run up the hill in the rain, where some of them had to dismount so as to lighten the traps for the horses.'

Choirmen and friends again demonstrated their hardihood in catching the 4.40 a.m. Midland Railway train for a trip to Blackpool, and enduring a journey of about five hours. The magazine contributor noted that the guide-book described Blackpool as the unrivalled seaside resort: 'A statement which, with all due respect...we venture to question... The place abounds in two things - places of amusement, and eating-houses...a great majority of those who patronise the place during the holidays go there chiefly for amusement, and not for fresh air; and in our humble opinion this is putting the cart before the horse.' This severe verdict concluded with the observation that very little shade was available in Blackpool, and that there seemed to be hardly any trees. In spite of these strictures, they had a very enjoyable day 'on the whole,' getting back at 11 p.m.

The Sneinton knack of getting into a muddle on days out was further demonstrated by the Sunday School teachers, who, as reported in October 1904, ventured by train to Matlock Bath. On the way home it was discovered that, owing to the carelessness of two of the party, 'We had left our tickets behind. This little incident which we naturally regarded as an exceedingly trivial one, caused notwithstanding a certain amount of consternation amongst the officials of the M.R. both at Derby and Beeston.' After explanations, all were allowed to continue their journey, and one cannot help feeling that they were fortunate not to have been travelling in 2003. Sunday School teachers or not, passengers today displaying such nonchalance over their lack of tickets would certainly be beset by 'revenue protection' officials, and might face a long walk home.

The 1905 Sunday School treat was held at Holme Pierrepont. Surprisingly this short journey was undertaken by rail, involving the older children in a trudge from Radcliffe-on-Trent Station to Holme Pierrpont and back. A correspondent explained that the four-mile walk from Sneinton to Holme was too much for children, and that the cost of car hire was prohibitive - this was, I think, the magazine’s first mention of the motor car. A special Great Northern train had therefore been engaged for the bigger boys and girls, while the infants were accommodated in a horse brake. Inevitably, one poor lad got his finger jammed in a carriage door, losing a nail. On returning home after these two route marches the youngsters were trooped up from London Road High Level Station to Sneinton church, where they stood to attention for the National Anthem before being allowed home to bed.

The choirboys enjoyed a day in Mablethorpe, where they chiefly occupied themselves in eating, cricket on the sands, and donkey riding. The eighty-mile journey home took almost five hours, giving occasion for ironic comment: 'Those who travel on the Saturday in Bank Holiday week must put up with these trifling inconveniences, which the railway companies seem more or less powerless to overcome.' The Great Northern Railway eventually deposited the lads in Nottingham a little before 11 p.m.

On the following Saturday the vicar's class visited the Dukeries, and were greatly impressed by Clumber chapel and Thoresby Hall. Returning from Edwinstowe to Mansfield by waggonette they experienced yet another incident, this time only the 'commendable promptitude' of one of the drivers averting the running-over of a child in Mansfield Market Place. In August the choirmen visited Scarborough in a saloon carriage chartered from the Great Central Railway. This was so cramped, low in the roof, and badly ventilated that some of the party chose to spend the homeward journey in the luggage compartment instead. Once again, readers may well empathize with these excursionists of a bygone age. 'The Queen of Watering Places' evidently came up to scratch, but a note of asperity was apparent in the comment that 'The return journey was accomplished in the extraordinarily short space of six hours, but this is, of course a mere detail.'

1906 saw no falling-off in Sneinton enthusiasm for outings, and further testing trips were undertaken. The choir party, still unrivalled in stamina, left by rail at an early hour for Liverpool, there embarking on a two-hour sea voyage to Llandudno. Managing four hours at the Welsh resort, they sailed back to Liverpool for a 'capital meal at the Bear's Paw.' Nottingham Victoria was reached at a quarter to one in the morning, with the magazine's usual keen interest in railway company performance revealed in the report. 'The Great Central Railway this year certainly treated us very well, as we feel sure that even the most ardent supporters of a rival system called the Midland Railway will readily admit.'

The 1906 Sunday School trip, to Holme Pierrepoint again, was utterly ruined by rain. It was pouring by the time the train reached Radcliffe, so the 500 children had to make do with tea in the servants' hall at Holme Pierrepont Hall, and games in the coach-house. The Radcliffe stationmaster got them off for home in an earlier train than had been arranged, and a cramped journey rounded off an uncomfortable day. The day was not quite ended, however; the weary children again stood in wet clothes at the church at 9 p.m. while a band played the National Anthem.

In September the choirboys, not yet sated with the delights of Skegness, again visited the favourite Lincolnshire resort. Several arrived to catch the train home 'in a panting condition,' while two others left their caps in the carriage. Four days later the Sunday School teachers experienced an ill-starred Saturday afternoon outing to Hickleton, near Doncaster, the estate of Lord Halifax. The Midland Railway failed to shine, the party not arriving at Rotherham until two hours after leaving Nottingham.

There followed a drive of 10 miles over hilly roads. This took 1½ hours, leaving the visitors little time to view the church and Hall before leaving Hickleton at 7pm. - incredibly they did not reach Nottingham until 11.20. The Midland's advertising slogan, ’The Best Way,’ must have evoked some hollow laughter after this performance.

Commonsense prevailed for the 1907 Sunday School treat, it being recognized that Holme Pierrepont was not a convenient venue. 'The getting of children in and out of the train, and the ticket collecting is always a business, and then the walk up from Radcliffe-on-Trent, possibly in drenching rain, as was the case last year, is certainly not exhilarating.' So Wollaton Park was chosen, where, through the kindness of Lord and Lady Middleton, a pet donkey was made available for rides, swings were put up, and the fountain turned on. Even now the children did not escape their customary plod; although special tramcars were laid on for them as far as Lenton, they had to walk about two miles in each direction to complete their journey.

An air of world-weariness crept into the reports of other outings in 1907. The choir had remained faithful to Liverpool and Llandudno, but this time the steamer was so small that few seats were available for the Sneinton party. Not only this, but the train journey home was 'somewhat slow and tedious.' And even Skegness, a venue so keenly relished by the choirboys only a year or two earlier, was beginning to pall: 'We confess to feeling a certain sense of monotony with regard to this trip, but after all what can we do?' Skegness, Mablethorpe and Sutton-on-Sea were evidently considered the only feasible destinations, and Skegness being the easiest to get to, they had gone there again. The boys had played cricket in the pleasure grounds of the Sea-View Hotel, accompanied by 'the dulcet strains of a gramaphone,' but, in spite of this exotic touch, the old magic seemed Jacking.

The first stage of the choirmen's 1908 outing was a journey to Sheffield by the Midland Railway. 'Sheffield! We think we hear some of our readers exclaim, well, that is hardly an ideal place to spend a choir outing.' After thus tantalising his readers, the writer revealed that from Sheffield they had set out in horse brakes for Chatsworth and Haddon Hall, some 16 or 18 miles away. Sneinton readers who possessed a Bradshaw might well have wondered why they had not taken the train to Rowsley, advertised as the station for both these stately homes, being within two miles of Haddon, and three of Chatsworth. Perhaps the long road journey was meant to be part of the day’s fun, but in the event the dust on the roads was considerable, and in 'an alarming incident' the rim of one of the wheels of a brake was found to be loose.

Notwithstanding last year’s feeling that this resort was becoming humdrum, the choirboys yet again visited Skegness. Perhaps the organiser had been inspired by John Hassall's classic Great Northern Railway 'Jolly Fisherman' poster, which made its first appearance in 1908 to remind holiday makers that 'Skegness is so bracing.' The journey followed the usual Sneinton routine: 'We didn't have many accidents, one finger was badly jammed in the door of the saloon, but amputation was apparently unnecessary, and the injury didn't seem very greatly to perturb the possessor of the finger, or interfere with his enjoyment. We believe that one or two caps somehow or other fell out of the window, but these are mere details.'

Having followed this saga of Sneinton outings, with its catalogue of predicaments and fiascos, the reader will gather that something really special must have occurred for the magazine to assert that one trip in 1909 was 'without precedent in the annals of Sneinton Parish Church.'

The hapless choir party were again the protagonists, their misadventures beginning when they lost their way on the North Staffordshire line en route to Dovedale. On being asked at a rural station (almost certainly Oakamoor): 'Is this right for Ashbourne?' a porter 'chuckled inwardly and told them they should have changed at Rocester. 'So out we bundled and walked back to Alton Station, where we encountered an infuriated station master who wilfully demanded excess fares. We then entered another train, changed at the next station, were savagely attacked by a swarm of wasps on the platform, and finally arrived at the end of our short journey at about 12 o'clock.' Never since Mr Footer in The Diary of a Nobody can anyone have so faithfully recorded day-to-day scrapes and humiliations as did these indomitable Sneinton day trippers. Somehow one is not surprised to learn that, in spite of everything, the choir had a most enjoyable day at Ashbourne.

The reporting of Sneinton days out continued until the end of the decade under our consideration. In June 1910 a group from the church men's class took a train from London Road Low Level to Harby & Stathern, a station remote from both of the villages named, and sited in the middle of nowhere in open fields.4 (On this expedition they had robust clerical reinforcements in the persons of the vicar, whose bicycle ride to Costock years before had clearly been no fluke, and one of his curates, who may well not have dared to decline the invitation.) From Harby & Stathern a walk of some five miles through woods to Belvoir Castle was greatly enjoyed: luckily the weather proved ideal. After viewing the Castle most of them opted for road transport to Bottesford to catch the train home, but a few diehards chose to walk these extra four miles. By Sneinton standards this was, perhaps, one of the gentler days out.

The choir preferred a trip to London in July, the non-stop 8.25 express getting them to St Pancras two minutes early. After Lord Henry Bentinck had shown them round the Houses of Parliament, the participants visited the usual sights of the capital. The day did, however, have a sting in its tail: 'The return train left St Pancras at 12.40, and needless to say, was not so expeditious in its movements as the morning train; as Nottingham was not reached till between four and five o'clock.' This being a Friday morning, it appears very likely that some of these heroes had to begin a day's work immediately after breakfast. It seems a suitably spartan note on which to bid farewell to the intrepid excursionists of Sneinton.

They had all by now, of course, become Georgians, rather than Edwardians. The short reign of Edward VII was over, and the First War War less than four years away in the future.

At the beginning of this article it was wondered whether the pages of Sneinton Parish Magazine from 1901 to 1910 would read like the last echoes of that old world. Some things have indeed changed beyond imagining. It is inconconceivable, for instance, that a vicar of Sneinton today could afford to finance the rebuilding of his church from his own pocket: and travel nowadays bears little resemblance to the Edwardian outings we have shared, from which the motor vehicle was conspicuously - perhaps blessedly - absent.

LONDON ROAD (LOW LEVEL) STATION, from which the 1910 excursionists to Belvoir Castle set out.

LONDON ROAD (LOW LEVEL) STATION, from which the 1910 excursionists to Belvoir Castle set out.On the other hand, Sneinton people a century ago were complaining about the weather, the railways, and the City Council. Controversy raged over reforms in the education system, and new trams were eagerly expected in the neighbourhood. In some ways the world may not have changed as much as we tend to believe.

1. Further information about Pullman may be found in Picturesque and worthy of inspection. Sneinton Magazine 72, Winter 1999/2000

2. Picturesque and worthy of inspection, as above, tells something about Colonel and Mrs Davidson

3. The 1903 timetables show, for example, that the fastest train did the journey from Nottingham to Stratford-on-Avon in 2 hours 9 minutes, changing at Woodford & Hinton (later Woodford Halse) from the Great Central to the Stratford-upon-Avon & Midland Junction Railway

4. This junction on the Great Northern/London & North Western Joint Line lost its passenger service in 1953. In 1910 the 15-mile journey from Nottingham London Road (Low Level) took just over half-an- hour

< Previous