< Previous

UNCONSIDERED TRIFLES:

A Sneinton recipe book

By Stephen Best

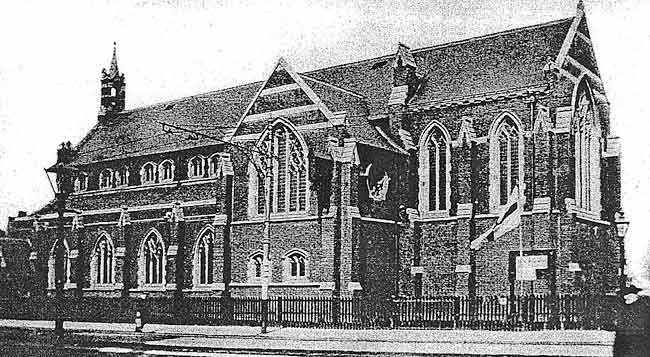

THE NEW ST CHRISTOPHER’S CHURCH BUILDING not long after its opening. A postcard view dated 1912.

THE NEW ST CHRISTOPHER’S CHURCH BUILDING not long after its opening. A postcard view dated 1912.AT THE BUS STOP A FEW MONTHS AGO a friendly neighbour mentioned that his wife had come across a couple of old books that might be of some interest to me. He didn’t sound especially hopeful, but I assured him I’d like to see them anyway. Like Autolycus in Winter’s Tale, the student of local history needs to be a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles.

When the books arrived, one proved to be a replica World War 2 ration book. The other was a little gem, hitherto unknown to me. And trifles do indeed come into this story, for it bore the fanciful title of YE NEWE SNEINTONE COOKERIE BOOKE.

Printed by W.P. Cranmer of Woolpack Lane, Nottingham, it is undated, but internal evidence places its publication date as 1911-12. In its limp blue covers, it was, although this is nowhere explicitly stated, evidently issued as a fund raiser for St Christopher’s parish church in Colwick Road.

The little book is essentially a compendium of useful recipes, many sent in by members of the congregation and other local worthies. Other contributions came from well-connected supporters of St Christopher’s, while the remainder may have been copied from similar cookery books, or submitted by friends from further afield.

As is often the case, the advertisements now seem every bit as diverting as the main text. Of the thirty-two examples in the book (all relating to Nottingham,) almost half were inserted by Sneinton businesses, or by concerns closely associated with the neighbourhood.

The connection with St Christopher’s is immediately apparent. The church was new, its permanent building having been consecrated as recently as December 1910. This replaced the tin mission church which had stood in Colwick Road for about a decade, and which afterwards became the church hall of its successor. During the summer of 1911 St Christopher’s was accorded the status of a separate parish.

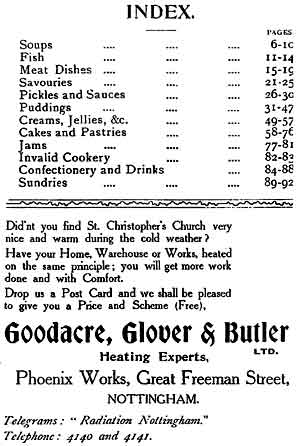

Near the beginning of the book the following announcement may be read: Didn’t you find St Christopher’s Church very nice and warm during the cold weather? Have your Home, Warehouse or Works, heated on the same principle; you will get more work done, and with Comfort. Drop us a Post Card and we shall be pleased to give you a Price and Scheme (Free), Goodacre, Glover & Butler, Ltd, Heating Experts, Phoenix Works, Great Freeman Street, Nottingham.

It is inconceivable that a notice would have been couched in such terms unless directed at St Christopher’s worshippers. Even so, Goodacres could hardly have hoped to gain many commissions from the rank and file of Sneinton churchgoers. They must have been counting on the book reaching a wider, more moneyed readership.

Halfway through the volume a further link with the church appears, in the form of this notice: St Christopher’s Church Monthly. An Illustrated Magazine of 18 pages, containing Parish News and Announcements, General Church News and Good Serial Story. Delivered to any address, price 1d.

That, I think, settles it, and the identities of many of the contributors further underline the St Christopher’s origin of this entertaining publication.

THE CONTENTS PAGE of THE COOKERY BOOK, with the prominent advertisement of the firm who had installed the church heating.

THE CONTENTS PAGE of THE COOKERY BOOK, with the prominent advertisement of the firm who had installed the church heating.Goodacres were evidently determined that no one remain in doubt about their multifarious skills, a second advertisement reminding locals that the firm produced Church Gates and Palisades. Ornamental and Constructional Ironwork All Classes of Engineering... A telegram to 'Radiation Nottingham' would reach them at Great Freeman Street, off Huntingdon Street. The business would, within a few years, move to London Road, near the Meadow Lane comer, and remain there for over four decades.

We shall look at the other advertisers later, but it is time now to consider the dishes featured in the COOKERIE BOOKE : the title, twee though it is, accurately reflects the air of period gentility which pervades the volume.

The first section dealt with soups, its opening entry immediately striking a superior note. This was submitted by no lesser a personage than Lady Henry Bentinck, daughter-in-law of the Duke of Portland, and wife of the Member of Parliament for South Nottingham. Lord Henry had in 1909 opened a bazaar to raise money for the building of the new church, and had spoken at its foundation stone-laying ceremony in March 1910.

Lady Henry was reported to have shown some sympathy with the women’s suffrage movement by stating in public on one occasion that she saw no reason why women should not have the vote. She was to live on until 1939, eight years after the death of her husband, who eventually clocked up the remarkable total of thirty years as a Nottingham MP.

It may be doubted whether Lady Henry Bentinck was at any time in her life required to roll up her sleeves in the kitchen, as before her marriage to the son of a duke she had been Lady Olivia Taylour, daughter of the Earl of Bective. She nevertheless offered a suggestion for Milk Soup, digestive and inexpensive.

The chapter on fish recipes began with another aristocratic offering; this from Lady Cicely Pierrepont, who rather modestly gave her address, Thoresby Park, as though some readers might by a remote chance have been unaware of it. Then aged 25, Lady Cicely was a daughter of the 4th Earl Manvers, lord of the manor of Sneinton and one of the patrons of the living of St Christopher’s. In 1915 she would marry Lieut.-Col. Francis Hardy of the Coldstream Guards.

Their marriage was to end in tragic circumstances in 1929. Husband and wife were following the Cottesmore Hounds, when Lady Cicely suffered a fall, and was concussed. She recovered from this mishap, but her husband, who had rushed to her side, died only a few days afterwards. The newspapers presumed that the cause was shock. Aged only 54, Colonel Hardy had served in the South African and Great Wars. Lady Cicely Pierrepont’s suggested dish for the book was Sole au Gratin, perhaps a bit exotic for some Sneinton residents in 1912.

Other fish dishes were suggested by local ladies. The Mrs Killingworth of Sneinton who put forward Crab Salad may have been the wife of George Killingworth, newsagent of 46 Sneinton Hermitage, or perhaps of a different George, a traveller of 32 Sneinton Hollows. Rather more down-to-earth were the directions for Fish Cakes sent in by Mrs Maddison of 75 Kentwood Road, wife of a man listed in the street directory as a signalman.

Turning to meat dishes, Lady Henry Bentinck was again to the fore with Ragout of Mutton, while a Mrs E. Dellow of Sneinton offered a practical recipe for Beef Rissoles. Her husband was John Samuel Dellow of 15 Kingsley Road, perfumer, Boots Cash Chemists.

Nestling nearby, between Hot Pot and Toad- in-the-Hole, were instructions for making Sausage Pudding, one of several contributions from W.J. Grundy, manager, of 'Glen Esk,' 33 Sneinton Hermitage. Mrs and Miss Grundy would both also appear later in the book.

In the savouries section readers were able to discover the secret of Kidney Omelette from the pen of Miss Milne of Sneinton. This was the first of a number of recipes from a family whom I take to have been the womenfolk of Dr J. Alan Milne of 61 Colwick Road, an address very close to St Christopher’s. The aforementioned Mrs Grundy included a favourite recipe for Macaroni Cheese; she shared a page with directions for making Savoury Eggs from a Lenton schoolmistress, Miss Lucy Glenday of Ashburnham Avenue.

The address, 'Old Basford Vicarage,' accompanied a brief suggestion for Cheese Omelette from a Mrs Vaughan. This lady’s husband, the Rev. Edward Marychurch Vaughan - a splendidly Trollopean name if ever there was one - was vicar of St Leodegarius. He had come to Basford from Daybrook, and would leave it to become rector of Clifton. Although the address of the vicarage at that time was Nottingham Road, Basford, the house lay behind Basford Cemetery, approached along the narrow country lane we know today as Perry Road.

In the part of the book devoted to sauces and pickles there appeared for the first time Mrs Taylor of Sneinton Dale, who deserves special mention. She was married to the Rev. John Henry Taylor, who had from 1906 to 1911 been chaplain of St Christopher’s mission church (officially, chaplain to Earl Manvers, patron of the living of Sneinton.) Until 1932 he would be the first perpetual curate of Saint Christopher’s (in effect, vicar) before moving to Calverton.

Before the handsome vicarage at the top of Sneinton Boulevard was ready for occupation, Mr and Mrs Taylor lived at 144 Sneinton Dale, between Port Arthur Road and Lichfield Road, in the building which now houses the local SureStart office. Taylor Close, off Sneinton Boulevard, is named after him.

Mrs Taylor contributed a tip for Tomato Sauce, and also cropped up in the pudding section, with Wafer Puddings. A Sneinton Dale neighbour of hers, Mrs Keywood, supplied the ingredients for Sponge Pudding. Her husband John was a coal merchant whose premises stood close to the bottom of Granby Villas, where the Mill Park now lies.

Feughside Pudding is, to me at least, an unfamiliar dish, but a recipe for it, with strawberry jam a main ingredient, was included over the name of no less a person than Mrs W.G. Player. William Goodacre Player of Lenton Hurst, Derby Road, was, with John Dane Player, a son of the founder of the great tobacco concern. In 1912 the directories listed him as Director, Imperial Tobacco Co. Ltd. A leading benefactor of the new St Christopher’s, W.G. Player was also one of the patrons of the living. Feughside, by the way, is a small place near the boundary between Kincardineshire and Aberdeenshire, in north-east Scotland. Perhaps the Players had spent a holiday there sometime?

A very detailed recipe for Mincemeat was sent in by Mrs Mellor, Mayoress of Nottingham. This description of her is the main reason for dating the COOKERIE BOOKE'S appearance as 1911-12, her husband Edwin Mellor having being elected mayor for this period. Councillor Mellor was a plain net lace manufacturer, whose premises occupied part of Hill’s Factory in Manvers Street, lying between Evelyn and Thoresby Streets.

Lady Henry Bentinck followed her soup recipe with a brief formula for a successful Ginger Pudding, while a very familiar Sneinton name appeared on the same page, with Mrs Claud Manfull’s recipe for Dainty Pudding. Her husband’s drug store was for decades a fixture at 58 Thurgarton Street, on the comer of Trent Road. Many local people will remember the wonderfully crowded shop window which, under the management of Mrs Manfull by the late 1950s, then seemed a veritable time- capsule.

A further family well-known in public life cropped up in subsequent pages, a hint on making Raspberry Pudding being sent in by Mrs Ball, Ex-Mayoress of Nottingham. Albert (later Sir Albert) Ball had been mayor in 1909- 10; at that time a land and estate agent, of 9 Cheapside, his home was at 43 Lenton Road, The Park. Within six years or so of the book’s publication the son of Alderman and Mrs Ball would be one of Nottingham’s greatest heroes, and holder of a posthumous Victoria Cross. The life of Albert Ball junior, air ace of the Great War, has been written several times, but it is a cause for regret that the full story of his father’s colourful business career has never appeared in print.

Lady Cicely Pierrepont chipped in next with Chocolate Pudding, sharing a page with Mrs Baker of 45 Ashfield Road, wife of Samuel Edward Baker, clerk. This lady contributed the formula for a successful Apple Charlotte.

In the following section - creams, jellies, etc. - Mrs Ball and Mrs Player dispensed advice on the making of Pineapple Cream and Chocolate Mould respectively, while Dr Thomas Burnie of 389 Mansfield Road, Carrington and 23 Regent Street knew a good way of preparing Raspberry Mould. Mrs Grundy of Sneinton Hermitage emulated her husband in compiling a lengthy recipe for Chocolate Souffle, and overleaf the Goddard family of Clifton made the first of several appearances in the book.

The Goddards lived at the School House, Clifton, where Henry, head of the family, was master of the Council School. More unexpectedly, he also acted as village subpostmaster. Goddard offered the formula for Prune Jelly, while his daughter Dorothy was responsible for Meringues.

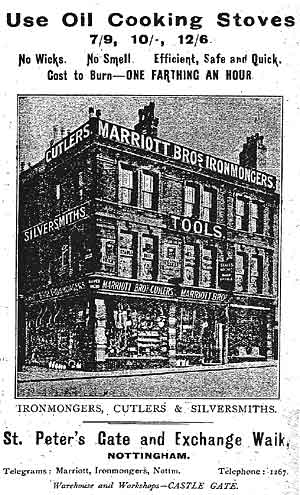

Under the heading of cakes and pastries, the indefatigable Lady Henry Bentinck suggested the ingredients for Swiss Roll; we must hope that Lady Henry’s cook was earning overtime for all these hints. Meanwhile Mrs B.S. Marriott of Sneinton Dale knew a thing or two about Pound Cake. Her husband was Bruce Shacklock Marriott, partner in Marriott Brothers., ironmongers of St Peter’s Gate, Exchange Walk and Castle Gate.

MRS MARRIOTT OF SNEINTON DALE submitted a recipe for the book. Her husband Bruce Shacklock Marriott was a partner in Marriott Bros., whose shop is seen here at the comer of Exchange Walk and St Peter’s Gate.

MRS MARRIOTT OF SNEINTON DALE submitted a recipe for the book. Her husband Bruce Shacklock Marriott was a partner in Marriott Bros., whose shop is seen here at the comer of Exchange Walk and St Peter’s Gate.A third member of the Goddard clan, Christabel, offered directions for a Victoria Sandwich, and Lady Sibell Pierrepont had all the necessary information for making something called Longbeat Cake. Barely out of her teens in 1912, Lady Sibell would, eleven years later, marry Hubert Davys Argles, steward to the Manvers Estate, and secretary of the Rufford Hunt. The couple died within twelve days of each another in 1968.

Mrs A. Maxfield of 28 Ashfield Road came next, suggesting the recipe for Cocoanut Pyramids. Perhaps these were eaten at her home to the accompaniment of sweet music provided by her husband Albert Ernest, teacher of the piano.

Beatrice Goddard of Clifton described how to make Chocolate Cakes, while Mrs Manfull reappeared with refined-sounding Afternoon Tea Cakes. The noted Sneinton surname Hombuckle accompanied the recipe for Cocoanut Cakes: for generations this family had kept the Lord Nelson pub, and a block of houses in Sneinton Hollows bears the name Hombuckle Villas. It seems likely, however, that the lady who submitted the recipe was married to Isaac Hombuckle, shopkeeper of 37 Kentwood Road. Just a few doors away from the Maxfields lived a warehouseman named John Dunstan, and his wife Mabel, who submitted a suggestion for Bakewell Tart.

We move now to the section of the book devoted to jams, Mrs Slingsby of Manor Street putting forward a concoction for Pickled Damsons, (which appeared to consist of little more than vast amounts of vinegar;) and what sounded like a much more palatable recipe for Apricot Jam. The Clifton Goddards remained in the picture: Madge with Marmalade, and Mrs Goddard with Lemon Curd..

At this date Sneinton Hill was the name for the steep stretch of Carlton Hill above Thorneywood Lane (now Porchester Road.) Here, in a house named 'Grouville', lived Mrs E.F. Harris, wife of Charles William Harris, clerk. She suggested a way of making Gooseberry Jelly.

From another outpost of Sneinton came a wonderfully varied group of invalid dishes, Mrs Geo. Johnson of Jarvis Avenue recommending a potion described as Strengthening Mixture for Consumption or Any Weakness. The chief ingredients of this were six eggs and half a pint of rum. On the same page the secret of Egg Pudding was confided by Miss Katharine Rorke, a mistress at Sneinton Council School in Sneinton Boulevard.

The final section was given over to sundries, a couple of neighbouring clergymen making rather feeble contributions. The Rev. Alfred Jackson of Corporation Oaks, senior curate at St Ann’s, St Ann’s Well Road, could offer nothing better than the gnomic advice to Let one fire burn at a time. What he meant by this is unclear, but as he was a parson his observation was no doubt received respectfully.

The Rev. Percy Holbrook, (later Canon Holbrook,) of Arboretum Street, was for many years vicar of Holy Trinity in Trinity Square. His tip was how to keep a small house fresh and healthy. Mr Holbrook not very surprisingly averred that this was best done by leaving a skylight or small window open: The cost of these improvements is not great, and the benefit is incalculable.

In addition to the local providers of recipes, there were a large number from people in places remote from Sneinton, whose connection with St Christopher's is not obvious, and who may indeed never have heard of the church. Two ladies in Beighton, near Sheffield, suggested several, while Elsie Simpson of Aberdeen was very appropriately credited with the right composition for Aberdeen Sausages. A Miss Abraham of Kirton Lindsey in Lincolnshire (Lindsey was spelt wrongly throughout the publication) proposed dishes which included Snow Pudding and Cocoanut Biscuit. A Mr J.A. Ford of Manchester, however, had nothing but whimsy to offer in his cure for indigestion: Little to eat, and plenty of time to eat it. Three physicians may be sought with advantage: Dr Diet, Dr Quiet and Dr Merryman.

The remaining dishes included several with unfamiliar, eye-catching names. Of these, Munster Sauce was composed largely of almonds and brandy. A clutch of intriguingly- named puddings included A Good, Hasty Pudding: Omnibus Pudding: Wall Pudding: Mysterious Pudding: and Manchester Pudding. The ingredients of all these, however, belied the promise of their names, being quite unexciting.

Among other cakes and pastries not yet mentioned appeared Aunt Katy’s Buns: Vicky Cake: and An Economical Cake, while one lady submitted directions for making Inexpensive Marmalade. From Yorkshire came the recipe for A Nice Summer Drink - capsicum and ginger essences, sugar, tartaric acid, and plenty of water.

Nearing the end of the book, four different prescriptions were offered for furniture cream or polish, one of them specifically stipulating the use of rainwater. The text closed with a touch of homespun philosophy entitled 'A Recipe for Happiness.' This will be quoted in due course.

After the people of St Christopher’s and the locality had tried out, or merely read the recipes, they could turn their attention to another feature of YE NEWE SNEINTONE COOKERIE BOOKE. As hinted earlier, the advertisements contained plenty for them to savour.

We have already noticed that Goodacre, Glover & Butler, responsible for the heating at St Christopher’s, had a couple of adverts in the book. One prominent Nottingham business, however, made its presence felt by means of a footer on almost every page - a slogan running along the bottom of the text. This was the fondly remembered Pearson Brothers of Long Row West, who bombarded the reader with four often-repeated messages: Pearson Bros. Cutlery is the Best: Pearson Bros. Ironmongery saves time and money: Pearson Bros. Cooking Utensils, Long Row: and Pearson Bros For Aluminium Cooking Pans.

Marriott Bros, have already been mentioned in passing. Their advert featured a photograph of imposing shop premises at the comer of Exchange Walk and St Peter’s Gate. No fly-by- nights, Marriotts would remain here for several decades. The building, is now occupied by Millett’s. Describing themselves also as cutlers and silversmiths, Marriotts urged readers to Use Oil Cooking Stoves, 7/9, 10/-, 12/6. No wicks. No smell. Efficient. Safe and Quick Cost to Burn - ONE FARTHING AN HOUR.

Foster, Cooper & Foster, furnishers of 63-64 Long Row West, occupied pride of place on the front cover of the book. They promised Comfort, Excellence of Quality, combined with Economy in Cost. These premises had a long association with the furniture trade, with Cavendish Furnishers following Fosters between the wars, and staying put here for several decades.

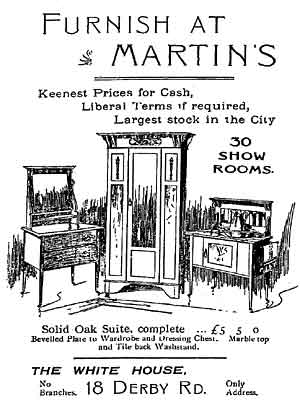

A second furniture shop, Martin’s, of The White House, 18 Derby Road, boasted 30 show rooms on their premises. Their selling points were Keenest Prices for Cash: Liberal Terms if required: Largest Stock in City. In 1912 Martin’s offered a solid oak suite, consisting of wardrobe, dressing chest, and washstand, for five guineas. It sounds extremely cheap now, but it is worth remembering that it would have represented well over a week’s wage for most Sneinton people in 1912. Martin’s traded here for many years; the site of the shop is now obliterated by the much later City Gate building developments at the bottom of Derby Road.

HOW TO FURNISH A BEDROOM in style in 1912 for five guineas, exemplified by Martin’s advertisement in the book. This price did not include a bed.

HOW TO FURNISH A BEDROOM in style in 1912 for five guineas, exemplified by Martin’s advertisement in the book. This price did not include a bed. Last of the City Centre furniture stores to feature in the COOKERIE BOOKE was William Truman’s of 47 Derby Road (comer of Upper College Street) and 12-14 Chapel Bar. Truman indulged in no gimmicks, merely claiming to sell The very latest in furniture, carpets and bedding. For years after Truman’s had gone, Hooley’s Garage occupied this Derby Road location. Now, however, there is once again a furnishing outlet here: this is New Heights, on the ground floor of the modem apartment block named Ropewalk Court.

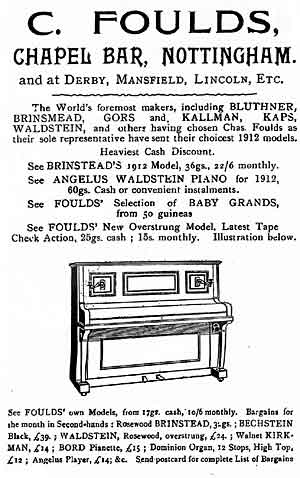

Also in Chapel Bar was the highly regarded firm of C. Foulds, piano sellers, who had branches at Derby, Mansfield, Lincoln, and elsewhere. Their own models were on sale from 17 guineas cash (payable at 10/6d a month,) but a Bechstein Black would set the purchaser back by £39. Even more inaccessible to the average Sneinton family would have been Foulds’ selection of Baby Grands, which began at 50 guineas, or an Angelus Waldstein at 60 guineas (£63.) Foulds were at 19-21 Chapel Bar until the middle of the inter-war period. The firm is still in business at Derby.

Two city centre clothing concerns advertised in the book. On the back cover readers were urged to shop at 5 High Street, home of A.S. Barnes, Specialist in headwear, neckwear and underwear. Special mention was made of the A.H.B. and Senrab (get it?) collars, exclusive to this outfitter. Barnes’s shop would be swept away in the 1920s, when one side of High Street was transformed just before, and during the building of the Council House.

SOME OF THE MOST EXPENSIVE ITEMS advertised in the COOKERIE BOOKE were the pianos available from Foulds’ of Chapel Bar.

SOME OF THE MOST EXPENSIVE ITEMS advertised in the COOKERIE BOOKE were the pianos available from Foulds’ of Chapel Bar.W.E. Jackson, haberdasher, lace and hosiery manufacturer, traded at 32 Drury Hill, a street sadly lost to Nottingham over thirty years ago. This firm remained here until the late 1930s, but another part of the Jackson commercial empire could be found at 71 Carrington Street, where they sold and repaired bags and trunks. Here they claimed to possess the Largest and Best Assorted Stock out of London, and to guarantee same day repairs to luggage. 71 Carrington Street soon afterwards disappeared during widening of Canal Street, and Jacksons moved to no. 61, being still in business there many years after World War Two. Their shop, together with nearly everything else on the east side of Carrington Street, was wiped away to make way for the Broad Marsh Centre, car park and bus station.

Once bought, clothes needed to be kept clean, and at 4 King Street was the central receiving office of P.P. Campbell, The Perth Dye Works. They offered to clean and press a gent’s suit for 4/-, and to dye one for 5/6d. This same trade continued at this address for decades, becoming Pullars of Perth just after the Great War. Thornton’s chocolates are now sold here.

Another well-established cleaning business was that of Thomas Long, Art Dyer and Dry Cleaner, at 55 Mansfield Road, just below the comer of Blue Coat Street, and now Austin Blowers estate agents. Long’s, who were still going strong here in the 1950s, addressed purchasers of the COOKERIE BOOKE in forthright terms: What every woman ought to know. That though a blouse, gown or costume be SOILED, GREASED or STAINED, they are far from useless, and by sending them to THOMAS LONG...they can be rendered spotlessly clean, revived in colors and pattern, restored in comfort and style.

20 Chapel Bar, near the top on the right-hand side, was the address of Jackson’s the Jewellers. Prominent in their advert were the startling words: Repairs for Nothing, but a closer reading disclosed these additional words (in much smaller type:) more than the bare cost of labour. Jacksons had this shop for a number of years more, to be followed by another jeweller and watchmaker named Marks.

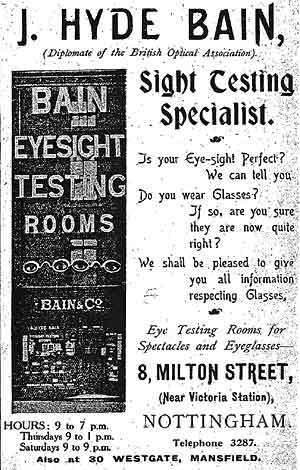

HYDE BAIN’S ADVERT featured this fascinating view of the shop frontage in Milton Street.

HYDE BAIN’S ADVERT featured this fascinating view of the shop frontage in Milton Street.At 8 Milton Street, a couple of doors from the Milton’s Head pub at the comer, were J. Hyde Bain, opticians. Their advertisement featured a photograph of the shop frontage, dominated by huge metal letters proclaiming EYESIGHT TESTING ROOMS, and two most alarming giant pairs of spectacles, complete with staring eyes. Apart from early closing day, Thursday, they remained open until 7 p.m. each evening, and until nine on Saturdays. Hyde Bain moved away to King Street in the 1920s, continuing in practice there for many years. Will Hill the tailors took over from them at 8 Milton Street, to be followed by Impey’s milliners and then Ascot Shoes.

Further up Milton Street, at no. 52, traded the chemists Bass & Wilford, (established 1820: telephone number 71.) Their advert made much of three proprietary cures. Of these, Bass’s Original Infants’ Preservative was hailed as The best remedy for Acidity, Wind, Gripes, Convulsions, and all ailments, during Teething.

The harassed mother might also have availed herself of Bass’s Nitoline, or Nursery Hair Lotion: A well tried and most Reliable and Effective remedy for Destroying all Nits... Finally, there was Dr Perolz’s Family Ointment, on the market since 1845: For Bad Legs, Abscesses, Tumours, Ulcerations, Carbuncles, Inflammation of the Eyes and Eyelids, Deafness, &c. This astonishing cure-all was available for as little fourpence-halfpenny, but with all due respect to Dr Perolz, an ointment that cured deafness sounds too good to be true.

Just three doors down from the Victoria Station Hotel, Bass & Wilford’s old shop became first a clothiers, and after that the Milton Cafe.

Newball & Mason’s Wine Essences were publicised in a full-page notice. This firm of manufacturing chemists in Beech Avenue, New Basford, frequently took adverts in publications with church connections, whose readers were reckoned likely consumers of Mason’s nonalcoholic drinks. They were assured that one bottle of wine essence, a pound and a half of sugar, and a gallon of hot water made A most delicious Wine suitable for the children during the festive season. Newball and Mason continued to market their highly-respectable beverages until long after World War 2. Their telegraphic address was the not very charismatic: ‘Extract, Nottingham.’

Another large advertisement was that of the Royal Midland Institution for Blind, whose workshops were in the imposing building that still stands at the top of Chaucer Street. Their shop, or saleshop, as they called it, was for a very long time at 65 Long Row West. The Institution pointed out that it depended entirely on public subscriptions, and that its prices were low. Brushes, bedding, towels, dusters, and cane-seated chairs were among the products of its blind workers.

Sisson and Parker was of course a city centre business known to generations of Nottingham people; its premises in Wheeler Gate are, as a branch of Waterstones, still functioning as a bookshop. Just over ninety years ago Sissons called themselves University Booksellers - the only university here then was of course the original University College in Shakespeare Street. In their advert, aimed at a churchgoing readership, the firm emphasized their stock of Bibles and New Testaments, the latter on sale from a penny each. One facet of Sisson’s business quite forgotten nowadays was their circulating library, available at a subscription of 10/6d a year.

The printer of the NEWE SNEINTONE COOKERIE BOOKE placed his own notice modestly towards its end. W.P. Cranmer announced himself as a Practical Letterpress & Lithographic Printer, and in the time- honoured phrase added: A Trial Order respectfully Solicited. Cranmer himself was a long-time Sneinton resident. Living in Holborn Avenue at the date of the COOKERIE BOOKE, he soon moved his business to Barker Gate, and his home to Durham Villas, Durham Avenue. Mrs Cranmer was still in residence here in 1953.

From those with businesses in or near the centre of Nottingham, we turn to advertisers in the volume who were based in Sneinton, or had a branch here.

Of the fourteen falling into this category, half had also paid for advertising space in St Stephen’s parish magazine between 1901 and 1910. These were all featured in Sneinton Magazine no. 89, but the other local businesses are here met for the first time.

Marsden’s local chain of grocery shops possessed two branches in Sneinton early in the twentieth century, in Gedling Street and Sneinton Boulevard. The firm’s advert in the cookery book, however, specifically mentioned only the head office, warehouse and bakeries at 22 Union Road. It also highlighted Marsden’s reputation as Tea Experts with a recommendation for their own blend at l/8d a pound: The Tea of the Season.

F. Skinner & Co. Ltd. were lesser-known provision merchants, though having at various times branches in Radford, Bulwell, Hyson Green, the Meadows, West Bridgford, and St Ann’s Well Road. Skinner’s took a full page advertisement for their shop at 68 Sneinton Hermitage, across the road from the police station. The Latest News! Skinners' are Expert Provision Merchants...Their Prices attract Customers. Their Quality begets Confidence.

Skinner’s Champion Blends of tea were slightly cheaper than Marsdens, and the shop also sold other goods on which it particularly prided itself: Best Preserved Ginger and refined English Honey... We especially recommend Bolsover High-Class Preserves, their quality and price always gives satisfaction.

The Sneinton Hermitage shop is now a private house - the useful little Hermitage shopping parade has long ceased to exist, and presents a forsaken face to passers-by today. After Skinner’s ceased to trade here between the wars, a fruiterer named Pickbum took over no. 68. A decade of two later the building became the rather unlikely headquarters of Mrs Stella Wigley’s School of Dancing.

In 1911 John E. Slight had not long taken over a grocer’s shop at 141 Sneinton Dale from Proctors, whose main premises were in Colwick Road. He urged local people to Try Slight's Malted Food for Children and Invalids, and was agent for Ceylindo Tea, a product otherwise unrecorded in these pages. The shop, at the comer of Ena Avenue, was for many years from the 1930s Bramley’s grocers, and currently accommodates the Azadi Asian Resource Project.

A few doors from Slight, Albert Mellows ran a confectionery and news agency at no. 131, for which he placed a modest advert in the COOKERIE BOOKE. Mellows was to remain here in Sneinton Dale until the Second War, and was followed by other confectioners, Ivy Torry and Arthur Cartwright. The shop is, at the time of writing, still in the same line of business as Naik Newsagents.

One Sneinton trader whose advertisement seemed to crop up in every local publication of the day was Bates the baker of 102 Sneinton Road. His familiar loaf of bread with the slogan Eat Bates’ Bread, It Bates All, duly appeared in the book.

Even Bates, however, could not rival one Sneinton firm in persistent high-profile advertising. This was Pullman & Sons, of Sneinton Street and Derby Road. Pullman’s advertisements have featured at length several times in Sneinton Magazine, so it will suffice here to mention that their notice in the cookery book took it for granted that everybody knew all about them, and merely reminded readers that The "Unanimous Verdict" in this District is that If you must have 20/- value for every £ you spend - Pullman & Sons, Ltd, the Cash Drapers, is the 'Shopping Centre’ for you. Make a Note of This!

Pullman’s close neighbour, the gentlemen’s outfitters Price & Beal, were just around the comer in Southwell Road, and had branches elsewhere in Nottingham. Their business would remain in Sneinton until the 1990s, outlasting Pullman’s by three decades. Their little advert in the book was a masterpiece of selfconfidence: Price & Beal are the Tailors for the well-dressed man. Waiting to see you - You know the addresses.

Another very long-lived Sneinton shop was Whiting’s, who occupied the imposing building that turns the comer of Colwick Road and Sneinton Boulevard. Well remembered as pawnbrokers, Whiting’s were in fact much more, as their big advertisement made plain. The Cheapest House in the District for Men’s Boys’ and Youths’ Clothing. Shirts that Wash and Wear Well. Special Line in Gents’ Box Calf and Glace Kid boots, 8/11 worth 10/6... White Quilts, Blankets, Tablecloths, Sheets, Ready Hemmed. Carpet Squares, Axminster Hearth Rugs and Special Pegged Cloth Hearthrugs, 5/11. Satin Walnut Bedroom Suite, £4.19.6. Walnut Sideboard, £3.15.6. Useful Sideboard, £2.15.6. Any Article May be Laid By.

Whiting’s, who occupied these premises when new in the first decade of the twentieth century, carried on their profitable and invaluable business at 1-9 Colwick Road well into post-war years. The building is now home to The Food Junction, which provides take away curries, kebabs and pizzas.

Two local laundries advertised in the COOKERIE BOOKE, as they did regularly in the St Stephen’s parish magazine. William Saxon’s Manor Laundry in Sneinton Hermitage stood at the foot of Lees Hill Footway. He claimed to have Branches Everywhere, which was perhaps pitching it a bit high for an empire with collection offices only in Sneinton, Forest Fields, and Radford. The National Laundry, with agencies in Sneinton Road and Trent Road, owned a works at Wilford Bridge, where they carried out High-class Family Work. Open- air drying.

William Osgarby, The Old Established Cutlery Shop, advertised from 9 Southwell Road, an address which would disappear in the 1930s when the wholesale market was built. Osgarby was Furnishing Ironmonger, Tinman and Cutler, stocking Baths, trunks, Wire netting, etc.

A possible relation of the Sneinton Dale grocer appeared in the person of F. Slight, dispensing chemist of 2 Colwick Road, whose advert stated that he sold Pure Drugs, Patent medicines, Nursing and Surgical Requisites, and that he offered Prescriptions Carefully Dispensed at store Prices.

Franklin Slight remained at the shop until inter-war years, when Boots began a long association with this address. Other pharmacists continued to trade here until the building entered a lengthy period of dereliction in the 1990s. It now houses the Sneinton Dental Centre.

There were of course dentists in Sneinton in 1911-12, and one such practice placed an advertisement in the book. Messrs. Staniforth and Griffin had a surgery at 1 Sneinton Bank Chambers, above the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Bank at the comer of Carlton Road and Manvers Street. Their stay here, however, proved short, and by 1916 they were advertising themselves as Artificial Teeth Manufacturers in Alfreton Road. By a quirk of coincidence, the former bank building, which eventually became the NatWest, today houses The Denture Clinic. The entrance to Sneinton Bank Chambers now displays the nameplate of the enigmatically-named Titanic Diving.

We end with an advertiser who also submitted a recipe for the book. Miss Dorothy Grundy, of 'Glen Esk,' Sneinton Hermitage, affected the genteel practice of using her house name only, and omitting its number, 33. Her line of work was Dressmaking. Ladies’ Own Materials made up in Latest Styles and Fashions. The Grundys would be lost to the Hermitage within four or five years, and like many other names we have found in the book, we should never have come across her had she not contributed to it.

There is not much else to report. The editor of the book, whoever he (more probably she) was, did not consider any kind of introduction necessary, or any section containing useful local information. As suggested earlier, perhaps it was hoped that the recipes would secure a sale far wider than Sneinton, and that parish pump details would be irrelevant for many purchasers. We do not know the price of YE NEWE SNEINTONE COOKERIE BOOKE, but it would be very surprising if it were more than sixpence.

W.P. Cranmer made a fair job of printing the little book. There were very few misprints, and for these the compilers were probably to blame. Perhaps the most exotic of these was the spelling of kedgeree as 'Kedegaree'. He laid out the advertisements well enough, and was sparing in the use of over-elaborate display typefaces. Cranmer could not, however, resist the temptation of using a heavy black-letter Gothic for the cover title. Unfortunately, the two photographs in the book, of Hyde Bain’s and Marriott Bros.’ shops, were, as they often were in directories of the day, rather muddy and indistinct. Again, this was probably the fault of photographer, rather than printer.

Cranmer did very little in the way of embellishing the text, and when he did employ a decoration, it was usually the same one. This was an odd motif, rather like a fancy brooch, or an elaborate belt buckle, which appeared several times in the course of the book, whenever the printer had a bit of space to fill up. It consequently provided a curious accompaniment to the components for Lentil Soup, Caledonian Pudding, Ginger Cordial, and finally, the previously-mentioned Recipe for Happiness.

This unsigned item ended the book, and, I suppose, exemplified the kind of values for which the new and hopeful St Christopher’s church stood. It ran as follows: Happiness is not to be procured like hardbake - in a solid lump - it is composed of innumerable small items. The recipe for its acquisition is simple, and therefore we ignore it. Love in marriage; fidelity in friendship; affection between parents and children; courtesy in intercourse; devotion to duty; and perfect sincerity in every relation in life; these are the ingredients of a HAPPY LIFE.

For all its imperfections, we should salute editor and printer for bringing out this little sidelight on the neighbourhood’s social history. Although, apart from the item just quoted, it points no moral, nor illuminates any great event in the story of the locality, it adds another piece to the patchwork of Sneinton’s past. We would, I believe, be the poorer without it.

My best thanks to Jenny and Dick Eminson, without whom I should never have seen the book in the first place. I am very grateful to them both.

My wife Sue has read this article in draft, and her keen critical sense has taken me to task for not saying more about the women who supplied the recipes, although including information about their husbands. In my defence I point out that street directories and most other reference books of the period are all too reticent on the subject of females, unless of the aristocracy. After the release of the 1911 census I may be able to rectify these omissions.

An account of how the new parish church came to be built can be found in Mission accomplished: the early years of St Christopher's Church. Sneinton Magazine 49, Winter 1993/94.

< Previous