< Previous

BATH STREET RAMBLE: Two Local Green Spaces :

PART 2: From burial ground to Blue Butterfly Scheme :

ST MARY'S REST GARDEN

By Stephen Best

THE RECENTLY WIDENED BATH STREET in about 1908. In this faint, but interesting postcard view, the cemetery gates seem to be shut. Does the notice on the railings refer to opening times?

THE RECENTLY WIDENED BATH STREET in about 1908. In this faint, but interesting postcard view, the cemetery gates seem to be shut. Does the notice on the railings refer to opening times?(Part One of this article gave an account of Victoria Park, and this second part deals with its close neighbour, St Mary’s Rest Garden.)

WHEN NOTTINGHAM SUFFERED A disastrous outbreak of cholera in 1832, it became clear that there was an urgent need of suitable and sanitary burial places for its victims. Most of the town’s churchyards were full, or closely surrounded by dwelling houses. Aid came from Samuel Fox, a Nottingham Quaker, owner of a grocer’s shop in High Street, and a rare man. Every Sunday he helped teach reading and writing at the Adult School in East Street, and he was an ardent opponent of slavery. More to the point, he was a member of the Nottingham Board of Health and, owning a field in a convenient location, gave it for use as a burial ground for St Mary’s parish.

This piece of land lay just outside what were then the built-up limits of the town. It was close to the Beck Works, which stood between the present-day Bath Street and Brook Street, and near a spot known as the Stone Waterings. In those days, before the building of St Ann’s Well Road, this stretch of the Beck was still an unculverted stream. The Stone Waterings (just a few yards north of where St Catharine’s church now stands,) probably got its name from the pebbly nature of the bed of the stream here, and because this was a place where cattle drank. Other explanations of the name refer to stepping stones, or blocks of stone set up to secure the banks of the stream.

To Samuel Fox’s field was added one which formed part of St Mary’s glebe land, and a third was later given or purchased. For many years the cemetery was known locally as Fox’s Close or the Cholera Burial Ground. It was also at various times termed St Mary’s Cemetery, from the parish which owned it: the St Ann’s Cemetery, following the construction of the adjacent St Ann’s Well Road; and St Catharine’s Cemetery, after the creation of a new parish and subsequent building of a church here.

In 1833 a chapel was built within the site, and two years later the burial ground was consecrated as St Ann’s Cemetery. The 1844 directory gave its area as about six acres. When the new ecclesiastical district of St Catharine’s was established in the 1880s, the cemetery chapel was pressed into service as its church. In the same decade a site at the comer of the cemetery nearest the junction of Bath Street and St Ann’s Well Road, was given by St Mary’s parish for the building of the new St Catharine’s Institute. This was pulled down a number of years ago, but one of its gate piers still survives, bearing the date 1884. A temporary tin church was built alongside the institute in St Ann’s Well Road, to be replaced in the 1890s by the permanent parish church building. In his 1929 history of the church and parish2 the vicar, John Lester, stated that no burials had taken place in this part of the burial ground. I am reliably informed, however, that human remains have been found recently during the course of preparing the site for new development.

Early in the twentieth century a further swathe of ground was removed to permit the widening of Bath Street. This work also involved the removal and reburial of a number of bodies. The old cemetery chapel had by now, however, been demolished, so its site was used for these reinterments. The location of the old chapel is marked by a white slab on the higher ground near the middle of the rest garden, near two small shrubbery beds. It is inscribed: ‘Within this enclosure are interred the remains of the persons formerly buried on the southern side of this Burial Ground, which were removed to this place consequent upon the widening of Bath Street, 1906.’ Regrettably, the memorial stones disturbed by this work were not preserved, and potentially interesting inscriptions thus lost.

Writing in the 1920s, the local historian Robert Mellors noted that the old cemetery was now kept locked, but that relatives of those interred there could gain access on application to the groundsman at Victoria Park.3 I remember riding past the cemetery on the no. 44 trolleybus as a young boy during the war, and from the upper deck seeing its many gravestones. Then, in 1946, a plan was drawn up by the Public Parks Committee for the ground’s conversion into a rest garden.

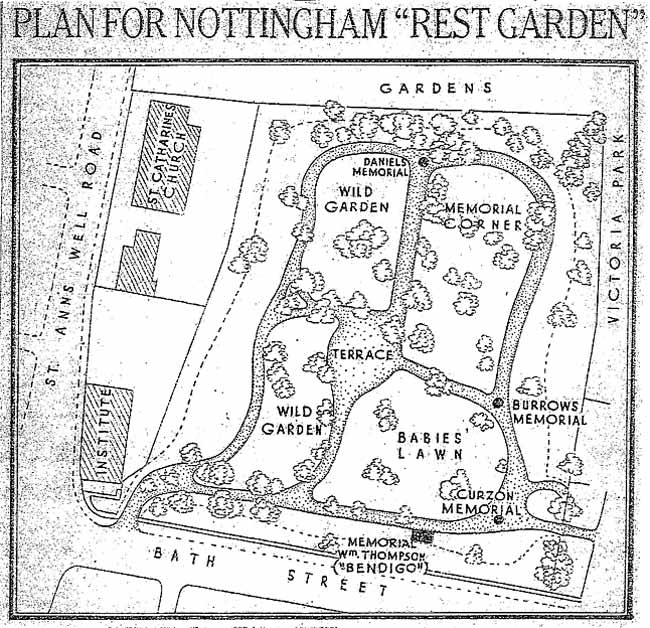

Most of the headstones were to be ranged along two of the perimeter walls, but four of the larger monuments would be left, placed at intersections of the main paths. One of the these was the recumbent lion marking the grave of the burial ground’s most celebrated occupant: William Thompson, the prizefighter Bendigo. The Nottingham Journal of 18 September printed a diagram of the proposed layout. In the light of a much more recent development here, it is interesting to see that a ‘wild garden’ was envisaged for the part of the rest garden, in which wild flowers and plants would be preserved.

The work of converting the burial ground was approved, but it was not until 27 July 1950 that the converted rest garden thus created was opened to the public. The annual report of the Public Parks Committee declared that: 'It is now a beautiful garden extensively used and greatly appreciated by the public.'

BENDIGO'S GRAVESTONE in 1987.

BENDIGO'S GRAVESTONE in 1987.The four prominent memorials may still be seen, Bendigo’s very close to the Bath Street wall. Remember, though, that before the widening of Bath Street Bendigo’s place of burial was closer to the middle of the cemetery than it is today. Bom in New Yard (now Trinity Walk), William Thompson appears, despite the myth that surrounds him, not to have been one of triplets. Nor was he the fairest and most chivalrous of opponents in the ring. After years as an habitual drunkard who was sent to the House of Correction on 28 occasions, he became a devout Christian on hearing a mission preacher. Bendigo holds the rare, if not unique distinction of having had a town in Australia, a bottled beer, and a tram named after him.

Bendigo died after a fall at his home in Beeston in August 1880. His funeral procession, in making the long journey to Bath Street, stopped at Canning Circus for a rest, some of the followers taking refreshment at the Sir John Borlace Warren pub (in recent years corrected to Borlase.). This can have done little to add to the solemnity of the occasion, and the subsequent graveside proceedings were enlivened by an old gentleman with an umbrella who knocked off the speaker’s hat. A full and extremely informative account of Bendigo’s career appears in Sneinton Magazine no. 47. 4

The myth, though, seems secure enough as long as the inscription at the head of his gravestone remains for passers-by to read: ‘In life Always brave, fighting like a lion. In death like a Lamb, tranquil in Zion. ’

THE MEMORIAL TO THE REV. HENRY DANIEL. Since this photograph was taken in 1987, the cross has been removed.

THE MEMORIAL TO THE REV. HENRY DANIEL. Since this photograph was taken in 1987, the cross has been removed.Over on the Lamartine Street side of the rest garden is the memorial to a more admirable figure, but one far less well known. This was the Rev. Henry Daniel, first vicar of St Luke’s church in Carlton Road. (The old City Mission building now used by the Congregation of Yahweh stands on the site of St Luke’s.) Daniel had become vicar in 1863, and this energetic young man had just started a parish mission in another part of Sneinton, Poplar Street, when he died of typhoid fever at the age of 32, in 1865. A very large assembly attended his funeral, and it was stated that when its head reached the cemetery, the funeral procession stretched unbroken all the way back to the church.5 On the plinth of Daniel’s memorial, we read that ‘He was the first incumbent of St Luke’s church in this town, and was greatly beloved and deeply regretted by his congregation, who erected this monument in remembrance of his untiring zeal and Christian love during the two years of his ministry among them. ’

Close to each other by the gate into Victoria Park are the two memorials to the Curzon and Burrows families. Although not commemorating anyone as well remembered as Bendigo, these, like the Daniel monument, were no doubt retained in situ on account of their imposing appearance, as compared with the general run of headstones in the cemetery. Both the Daniel and Burrows monuments have unfortunately lost much of their dignity during recent years. The cross has been removed from the top of the Daniel memorial, while the once impressive Burrows composition is now bereft of the short spire, with knobbly finial, which formerly crowned it.

THE BURROWS MEMORIAL IN 1987. It has since lost its spire; nothing remains above the gabled stage.

THE BURROWS MEMORIAL IN 1987. It has since lost its spire; nothing remains above the gabled stage.A number of the more modest stones, now ranged along the walls, became obscured by invasive shrubs over the years, and many of the inscriptions were consequently very difficult to read. Recently this vegetation has been much too thoroughly pruned away, with considerable loss to the picturesque quality of the ground. One stone which is still substantially hidden behind bushes is, however, well worth the labour of discovery. This is in memory of Thomas Bettney junior, ‘Who was drowned in the River Trent near Stoke Bardolf in a daring swimming venture on the 28th of July 1861, aged 21 years. His loss was deeply mourned by a large circle of friends and acquaintances.’

Clearly, a story lies behind a gravestone inscription such as this, and the local newspapers of the day reveal a sequence of events that would seem ludicrous, were they not so tragic. Perhaps the best account is in the Nottingham Journal of 9 August: ‘SHOCKING CASE OF DROWNING - On Sunday morning last, a young man named Thomas Bettney, aged 22, son of Mr Bettney, pipe maker, Station Street, met with his death under circumstances which are much to be regretted. The young man, it seems, left the Trent Bridges on Sunday morning in company with a friend, and sallied down the river in a boat with the intention of meeting Mr Hammersley’s steam boat, which, we understand, was coming in an opposite direction.

When they arrived opposite the village of Stoke they met the steam boat, and were taken into it. Immediately after, the deceased, who was a tolerably good swimmer, proposed to strip and have a bathe in the river. Some of those on board remonstrated with him on account of the coldness of the water, but he refused to hear, and made use of the expression, ‘Don’t be afraid; a man that’s born to be hung will never be drowned.’ Having divested himself of his clothing he jumped from the packet into the river, and swam to the side without difficulty. He again plunged into the water, but in following the steamer he was suddenly lost sight of, and was never seen afterwards.

An active search was at once commenced for the body, but with no success up to the present. It is the general impression that the young man was seized with cramp whilst in the water, and was thus prevented from gaining the side. The event has caused a painful sensation in the town, and has cast a gloom over the circle of his friends and acquaintances. ’

A week later the same newspaper reported the holding of an inquest on Thomas Bettney at Gunthorpe. The young man’s body had been recovered about 6 o’clock on the morning of Friday 2 August, five days after the accident. The Gunthorpe ferryman found it floating downstream, and Bettney’s remains were taken out of the water and removed to the Unicorn public house in the village, where an inquest jury returned a verdict of accidental drowning. It was again stated that an attack of cramp had caused the poor lad’s downfall.

This fatal mishap seems to have occurred in very strange circumstances. Mr Hammersley’s boat is referred to in the Journal as a packet, with the implication that it carried cargo between ports or plied for passengers. There is, however, no river carrier or public pleasure steamer proprietor of this name listed in any Nottinghamshire or Lincolnshire directory of the period. Although some river carriers did advertise daily voyages, it seems more likely that the vessel met by Thomas Bettney on this Sunday was a pleasure steamer.

Even so, it is scarcely credible that, on board a vessel plying publicly, Thomas Bettney would have taken the liberty of removing his clothes. And what had happened in the meantime to the boat in which he and his pal had sailed downstream to meet the steam vessel? One can only presume that it had been taken in tow by the latter.

My own speculation is that this may have been a free-and-easy, pre-arranged meeting between Bettney and his companion, and friends aboard Hammersley’s boat. There were very few Hammersleys in Nottingham at that date, but among them was William Hammersley, timber merchant and sawyer, who lived and worked in Parkinson Street, a turning off Station Street, and only a few yards from Bettney’s home. As very close neighbours, the Hammersley and Bettney families must have known each other. If the ownership of a steam boat may sound beyond the means of a man in Hammersley’s line of trade, it may be mentioned that his was a substantial business, employing a large number of men and boys. He even had easy access to the water, as his sawmill premises abutted on to the Nottingham Canal. All this is, I emphasize, only conjecture, and it still leaves several questions unanswered.

I suggest, though, that it does provide a possible explanation of the tragic event at Stoke Bardolph.

Its is worth noting that, even in July, fellow passengers on the boat cautioned Thomas Bettney that the Trent was too cold for safe swimming. The papers gave only a few column inches to his drowning, but the Nottingham press had plenty of other events to engage it during this week in 1861. The earliest major battle of the American Civil War had been fought a week earlier, on 21 July, and the Nottingham Journal devoted considerable coverage to the Confederate victory at the first Battle of Bull Run, or Manassas.

Thomas Bettney junior had worked for his father in the family pipe-making concern. The older man, however, had another business interest, as keeper of a beerhouse in Station Street, the Devonshire Arms. The Bettneys’ closest neighbours were Mr and Mrs Summers of the Commercial Hotel in the same street. Nine years after Thomas’s drowning, they too suffered the loss of a son in tragic circumstances when George Summers, a most promising Nottinghamshire cricketer, died aged only 25 after being hit on the head by the ball at Lord’s in a match against MCC in June 1870.

Two other gravestones standing beside the rest garden’s boundary wall commemorate sudden deaths. The first is to Willie Morris, aged five, who was accidentally drowned in August 1865. The Morris family lived in Pomfret Street, in one of the poorest areas of Sneinton. The little boy fell into the canal not far from his home, and the jury found that he had died as stated on the gravestone. The bereaved parents, however, had to endure an inquest which stretched over three sessions, rather than one, held at the Fox and Hounds public house, at the comer of Barker Gate and Machine Street. The site of Pomfret Street is now under the City Transport bus garage, while that of the Fox and Hounds is now part of the Ice Arena.

On the first day of the inquest, one of the jurors, a butcher named Burton, turned up wearing a bloodstained apron, and carrying his butcher’s steel. Coroner Michael Browne commented so unfavourably on Burton’s unsuitable appearance that, when the jury retired to view the body, the butcher took himself off in a fit of pique. The jury reassembled on the following day, with Burton present; another juror, however, named Kyte, was not. The infuriated coroner had to fix a third day for the inquest. When all the members did manage to turn up together, Browne seems to have been more concerned about the duties of jurymen, and the dignity of the coroner’s court, than he was about the feelings of the Morrises.

Burton had been far from penitent on the previous day, and had 'ignorantly abused’ the Coroner, who threatened him with a fine. Kyte, however, was apologetic about his absence, pleading that he had been very busy in the market on that day, and that the inquest had quite slipped his mind. Unimpressed by this, Browne told him that he, too was liable to a fine of £50, but he eventually decided not to impose such a punishment.

We do not know whether Mr and Mrs Morris were present on every occasion, but all this delay can only have intensified their distress. An exceedingly unlucky family; the Morrises also lost a daughter, Lizzie, at the age of four, while Mr Morris himself died at 38.

The second headstone stands to the memory of Thomas Mayfield, ‘who was accidentally killed by a fall’ on 5 November 1874, aged 65. The date is a familiar one, and indeed played a significant role in Mr Mayfield’s sudden death. A framework-knitter, he had left his home at 19 Campbell Grove, just behind Bath Street Cricket Ground, and hardly a hundred yards from his eventual burial place, to walk up Blue Bell Hill. At this date there was comparatively little housing development here, and the hill made an excellent vantage point ‘for the purpose of obtaining a better view of the bonfires which were being held in the town in commemoration of Guy Fawkes’ day.’ Unhappily, this was a dangerous place to walk around after dark, as the Nottingham Daily Express subsequently made clear: ‘The hill is interspersed with embankments, and it would seem that whilst enjoying the sight the deceased suddenly fell over and sustained fatal injuries. ’

Mr Mayfield’s body was found between seven and eight the next morning by Henry Loverseed, member of a well-known Nottingham firm of builders and contractors, who was on his way to work. 'The body was conveyed to the Police Station...Dr Herbert Taylor was called in to see it, and the general supposition is that the neck of the unfortunate man is broken.’ The newspaper considered it pertinent to remind its readers that his son, Corporal Mayfield, was one of the best shots in the Robin Hood Rifles.

The manner of Thomas Mayfield’s death elicited a ferocious letter to the editors of the Nottingham Daily Express on 10 November. Under the heading 'DANGEROUS HOLES' Thomas Clarke of 28 Promenade accused Nottingham Corporation of neglecting to ensure the safety of the public: 'If proof of this were wanting, it is furnished in the death of my near neighbour Mr Mayfield, of Campbell Grove. In proof of what I say, he might have lost his life or fractured his limbs six months since, much nearer his own home close to or within 20 yards of his own front door, on the Paddock, New Sneinton, or the cricket ground, as it is termed, where holes ...were dug all round the Cricket Ground for the planting of trees. These holes were suffered to remain open with no defence of any kind...to warn people of their danger... ’

Mr Clarke had visited the Corporation Offices, where he ‘mentioned one hole in particular, far more dangerous than the rest, being within a yard or so of the path where people passed to the twitchell, and where poor Mayfield had to pass to his house, twenty yards from where this hole was dug.’ Clarke related that, following his complaints, the worst hole had been protected by a barrier, and all the others on the Cricket Ground filled in.

It is interesting that Mr Clarke referred to the ground as the Paddock. During the nineteenth century few seem to have been at all sure of what it should be called. Meadow Platt Cricket Ground: Bath Street Cricket Ground: Bath Street Recreation Ground: Robin Hood Street Cricket Ground; all these titles and others appeared in print, and we now find that there was at least one other local name in use. The Paddock suggests something less than a genteel ornamental ground, and indeed an old gentlemen wrote to Nottinghamshire Guardian in 1925, recalling that the place had, in those early days, been 'a huge area with some swings, but given up generally to a number of rough characters.’

The ‘twitchell’ refers, I think, to the pedestrian path through Robin Hood Terrace, leading off the park. Clarke’s motive was no doubt all very public spirited, but we may wonder how the Mayfields felt about the death of their head of family being used as a stick with which to beat the Corporation. We almost began this article with people grumbling about the state of the Bath Street Cricket ground, and with Mr Clarke we almost end on a similar note.

Despite the cutting-back of shrubs already referred to, and the loss of some trees, St Mary’s Rest Garden is a very agreeable place today, and the maturing meadow will further enhance it. It is marked by two stakes bearing labels which tell the visitor that this a ‘Blue Butterfly Scheme. Grasslands for Wildlife.’ So a project first mentioned as long ago as 1946 is gradually taking shape here.

Less happy is the possibility of a tall building springing up on the site of St Catharine’s vicarage, which would not only loom over the open space, but also overwhelm the former church building next door. We await developments.

We end this brief account of the Bath Street green spaces with a pleasant, and rather hopeful recent addition. Within a group of saplings stands a roughly hewn block of stone with a small metal plaque bearing these words: ‘This grove of trees was planted on 27th February 2003 by Nottingham Inter Faith Council. Baha’is, Brahma Kumaris, Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, Quakers, Sikhs. Growing in faith side by side. ’

Bath Street has never been regarded as one of Nottingham’s more beautiful or fashionable locations, but it lies in an area of the city which is by no means devoid of visual interest. The fact that it has never lain within the historical bounds of Sneinton parish is no bar to its being championed by this magazine. After all, Sneinton Market is only a short stone’s throw away, and even during the nineteenth century locals considered the district to be part of Sneinton, as Thomas Clarke’s letter of 1874 indicates.

It came, therefore, as very welcome news to this magazine that Sneinton Market and its environs have been designated as a conservation area by the City Council.

A number of buildings and features of this neighbourhood have been mentioned in Sneinton Magazine over the past 25 years. These include Victoria Park itself: Promenade: the old Town Mission Ragged School: Victoria Buildings (now Park View Court:) the former Bancroft’s Factory in Robin Hood Street: Victoria Baths, the former Wholesale Market: and the erstwhile St Luke’s School. Having recently argued its merits in print,6 this writer is especially glad to learn that the City Transport bus depot’s noteworthy frontage is to be included in the Conservation Area.

Sneinton Magazine, in association with its publisher, the Sneinton Environmental Society, has tried to do its share in keeping this unsung bit of Nottingham in the public eye, and it is intended that more will be written about some of these buildings in future issues of the magazine.

There have been success stories in recent decades, such as the Ragged School restoration and the modernisation of Victoria Buildings. The conversion of the Wholesale Market into small business units must be considered only a partial success while so many of these continue to stand empty. The demolition of recently firedamaged buildings in of one of the former market avenues is not a good sign, nor is the immediate conversion of the resultant vacant site into yet another car parking lot, complete with minatory notices. Although there is plenty for local environmentalists to feel pleased about, much remains that requires our vigilance.

THE PLAN FOR CONVERTING THE CEMETERY into a REST GARDEN as it appeared in the Nottingham Journal of 18 September, 1946.

NOTES

Part 1

1. 'The making of Victoria Park..’ Sneinton Magazine 54-55, Summer 1995

Part 2

2. ‘Dear S. Catharine’s. ....a history of the church and parish of S. Catharine, Nottingham, by the Vicar.’ Nottingham, printed by Hill & Tyler, 1929

3. ‘The gardens, parks and walks of Nottingham and district., ’ by Robert Mellors, Nottingham, Bell, 1926

4. ‘Bendigo the boxer,’ by Krzystof Cieskowsld. Sneinton Magazine 47, Summer 1993

5. ‘A low, unpretending building: the story of St Luke's church.' Sneinton Magazine 19, Winter 1985/6

6. ’A very poor area: the metamorphosis of the Carter Gate/ Manvers Street area: pt 3. ' Nottingham Civic Society Newsletter 122, September 2003

Unless otherwise indicated, all illustrations are from photographs by the author.

This article is for Ken Brand, who has for years listened patiently to the bees in my local history bonnet, and who, like me, dreams of the day when we discover the identity of the architect of Bancroft’s Factory.

< Previous