< Previous

BATH STREET RAMBLE: Two Local Green Spaces :

PART 1: From eyesore to Award Winner : VICTORIA PARK

By Stephen Best

TEN YEARS AGO AN ACCOUNT OF THE early years of Victoria Park in Bath Street appeared in numbers 54 and 55 of Sneinton Magazine. While writing it, I could not help feeling that the park had somehow never been as fully appreciated in and around the neighbourhood as it deserved to be;

In 2004, however, justice was done when Victoria Park received a Green Flag Award in recognition of recent improvements made.

Before discussing these, and describing the park as it is today, a short outline of its history is appropriate. The park’s ups and downs during the nineteenth century are traced in much greater detail in the earlier article just mentioned.1

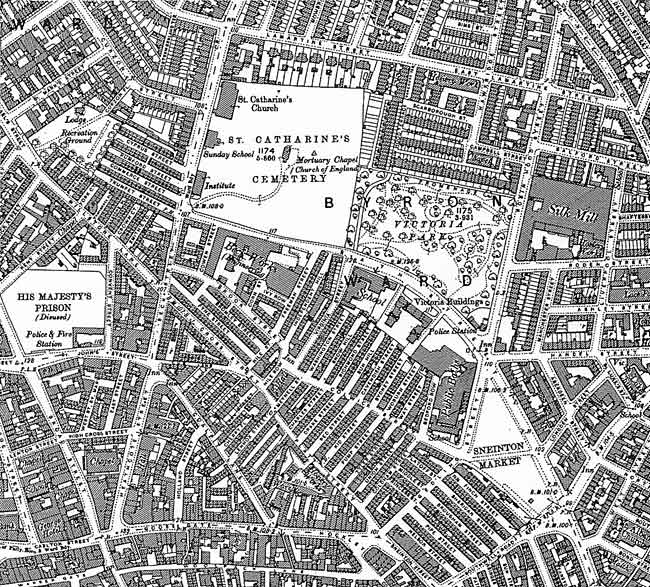

We first hear of a recreation ground on this site on the map of the 1845 Nottingham Inclosure Award, which refers to the open space as the Meadow Platt Cricket Ground. Next to it was the St Mary’s Burial Ground, now linked to Victoria Park, and with it forming a leisure area stretching down Bath Street from Robin Hood Street to St Ann’s Well Road. This cemetery, on land donated to the town by the prominent Nottingham Quaker Samuel Fox, gave Bath Street its former name, Burying Ground Lane. Now St Mary’s Rest Garden, it too flies the Green Flag, and an account of this interesting plot of land forms the second part of this article.

One consequence of the Inclosure Act was the rapid building-up of land north and east of Bath Street, and the cricket ground soon became a valuable recreational feature, surrounded as it now was by the expanding Borough of Nottingham.

By the 1870s the Town Council was engaged in considering improvements to the site, which for the time being came to nothing. Almost from the start there had been complaints about the shortcomings of the ground, and about some of its patrons, who included a number of rough customers. The 1870s saw Victoria Buildings built on the opposite side of Bath Street, and this pioneering block of municipal housing soon experienced its share of crime and hooliganism. It seems likely that some of the more lively occupants of the Buildings used, and misused the cricket ground just over the road.

During the following decade the ground experienced a variety of problems. Imperfect drainage proved a regular headache, and residents and passers-by were repeatedly annoyed by ball players. This resulted in an instruction to the policeman who lived in the adjacent lodge that cricket should be not allowed close to the streets which bounded the area.

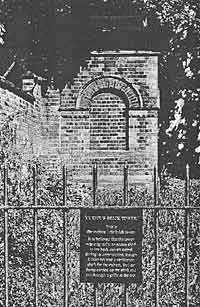

The 1880s brought a major upheaval, with the construction of the Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert. This substantial engineering project brought about the improved culverting of the Beck Stream, which originated at St Ann’s Well, and flowed beneath St Ann’s Well Road to its junction with Bath Street. From there its course led under Brook Street and Manvers Street. Although it had, over the years, been culverted in stages, it was hopelessly ineffective as a sewer. The projected culvert would therefore leave the old course of the Beck near the bottom of St Ann’s Well Road, its course taking under the Bath Street Cricket Ground, then beneath Sneinton Market, on its way to an outfall in the Trent at the end of Trent Lane,

A 2004 VIEW of THE BRICK TOWER built in the 1880s in connection with the Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert.

A 2004 VIEW of THE BRICK TOWER built in the 1880s in connection with the Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert.The contractors leased about 1,000 square yards of the cricket ground for the duration of the works, and provided the park with a feature which has mystified many people over the years. This is the little tower which still stands close to the boundary wall between the park and the former burial ground. Originally providing access to the culvert during construction, it thereafter became a ventilation shaft for the sewer tunnel, foul air being carried out through a grille at the top.

Behaviour in the cricket ground failed to improve, and eventually the police set an upper age limit of thirteen on those allowed to play there. Unsurprisingly this rule seems to have had little effect, local clergy being driven to grumble about acts of trespass in the burial ground by indisciplined cricketers.

Local people, meanwhile, continued to be exercised by the mucky state of the grounds. When it was wet, as we have heard, the drainage could not cope with the rainwater; when dry, an excess of dust caused much annoyance. Not only this, but residents urged the committee to improve the lighting, on account of the ‘purposes to which, owing to its badly lighted state, the ground was put.' The exact nature of this misbehaviour can only be guessed at, but it was troublesome enough for a large lamp to be erected on the site.

The Borough Engineer, Arthur Brown, had been requested to report on the state of the ground, and to suggest improvements, especially with regard to drainage. The Public Parks Committee, however, put off consideration of the report, and it was generally felt that the cricket ground needed major alterations, rather than minor improvements.

In 1891 two local councillors presented to the committee a petition signed by well over 500 local residents, asking that the cricket ground be improved, and after considerable humming and hawing on the part of the Borough Council, the Engineer was instructed to prepare plans for a redesigned and improved recreation ground. From this moment the modem park began to take shape.

In the following year the Public Parks Committee looked at no fewer than four schemes for an improved ground, but the Borough Engineer’s sensible and realistic plan was adopted. He proposed a wide shrubbery along the north and west sides, ornamental walks and beds in the grassed interior of the ground, and an asphalted play area, with swings, close to the Bath Street gate.

There followed the business of financing the improvements, and a delay in obtaining a loan from the Local Government Finance Board prompted a deputation from Nottingham United Trades Council to attend a meeting of the Committee in February 1893. They argued that severe unemployment in the town made it essential that an early start be made on the project, and indeed the job did begin almost immediately afterwards.

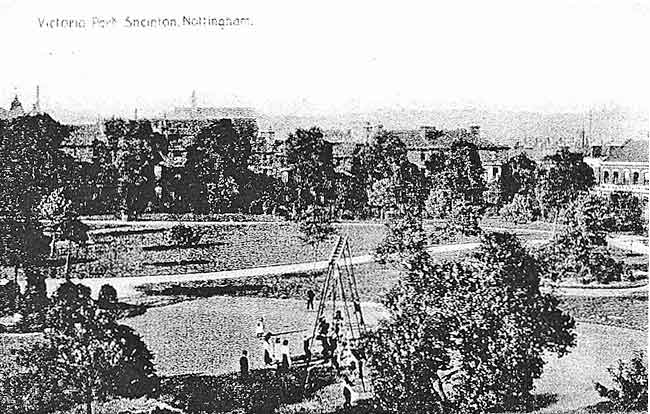

A VIEW OF VICTORIA PARK from the roof of Victoria Buildings. From a postcard of about 1907.

A VIEW OF VICTORIA PARK from the roof of Victoria Buildings. From a postcard of about 1907.The work went on throughout 1893, with the task of levelling and draining the site proving the major engineering difficulty. Various alterations were made to the plan as work progressed and it was not until the spring of 1894 that the remodelled Bath Street Recreation Ground was ready for opening.

Victorian Nottingham was always eager to embrace the opportunity of a public jamboree, and the inauguration of the park on 7 May attracted a grand turnout of municipal worthies. The chairman of the Parks Committee, Alderman William Lambert, was accompanied by a dozen or so members of the Council, and it was a happy coincidence that a noted Sneinton resident and businessman, Ald. Frederick Pullman, was Mayor that year. Greeted by much applause, Pullman told the crowd that he had known the area for many years, and had always felt that the recreation ground needed improving. He did not exaggerate in claiming close associations with the neighbourhood. Pullman’s extensive and thriving drapery emporium was in Sneinton Street, only two or three hundred yards from Bath Street, while his house was in Castle Street, Old Sneinton. Alderman Pullman congratulated everyone involved in the remodelling, and, in declaring the ground open, named it Victoria Park.

Pullman also paid special tribute to John Sharkey, a former town councillor who had been specially prominent in pressing for the park improvements to be carried out. Sharkey no doubt wondered why the ungrateful voters of the area had failed to re-elect him.

The Nottingham Daily Guardian of 8 May thoroughly approved of the new park. One of its laudatory sentences was so full of compliments and subordinate clauses that it only just managed to totter to a conclusion: ‘The transformation of the old Bath Street playground, which had for years been an eyesore to that particular portion of the Sneinton district, into tastefully laid out walks, grass lawns, and shrubberies, provision also being made for the children in the matter of swings and other means of recreation, and which is henceforth to be known by the title of ‘The Victoria Park,’ is one that cannot fail to meet with the fullest appreciation, not only of the residents in the neighbourhood, but of the town generally.’

The Evening News report of the occasion suggested a rather more animated scene: ‘A very large crowd, numbering several thousand persons, awaited the opening of the gates with evident interest, and as soon as the gates had been thrown open the grounds were thronged, the younger people making immediately for the swings which were kept going all night.’

Within a year of the opening of the newly revamped park, vandalism and other misbehaviour was again so prevalent that the police were asked to station a constable at Victoria Park, to assist the caretaker in keeping order. (What had happened to the officer whose assistance had been called upon in earlier decades?) The nineteenth century ended and the twentieth began, however, with mention of pleasantly civilized entertainment at Victoria Park - concerts by the City Police band.

Anyone familiar today with Victoria Park who looks at the 1901 large-scale Ordnance Survey plan of the area will be struck by how few changes have been made to its layout since then. The remodelling of 1894 gave us, more or less, what we still see today, and the intervening 111 years have altered it only marginally.

THE PARK (2004) with the former open-air school in the background.

THE PARK (2004) with the former open-air school in the background.One change which has occurred might have interested the policeman responsible for helping out the caretaker. This officer would have had to travel only a few yards to take up his duties, from the police station which stood for many years at the comer of Robin Hood Street and Bath Street. Built in the standard municipal official style of the day, it remained operational until well after the Second World War. Modem premises succeeded the old one, but the police eventually gave up the building. Since they moved out, it has had a variety of uses, including a period as a bookmaker’s. It now belongs to Ernest Smith, the monumental masons.

Two decades into the twentieth century, a new structure appeared in Victoria Park’s northwest comer, close to the comer of Promenade and Robin Hood Terrace. First mention of what would eventually become a complex of several buildings occurs in Nottingham Corporation documents shortly after the end of the Great War. On 10 May 1920 the Education Committee minutes noted that: ‘The Open Air Kitchen Centres. which the Education Committee have recently established in the Public Parks, by the very kind co-operation of the Public Parks Committee, have been so phenomenally successful in improving the health of delicate children...and in promoting the health and education of scholars generally... ’ One result of this success was that additional accommodation was now thought necessary at Victoria Park - one extra classroom, cloakrooms, and latrines. The 1920 yearbook of the education authority listed Victoria Park as one of several locations for ‘branch recovery classes,’ subsidiary to the open-air recovery centre at the Arboretum.

Subsequent annual reports of the Education Committee explained what Nottingham was trying to achieve at open-air schools such as Victoria Park. The report for 1924-25 stated that: ‘Habitually Delicate Children are received in the Committee’s Open-Air Recovery Centres in the Public Parks, all of which include well- equipped kitchens for cooking and serving meals specially arranged by the School Medical Officer. The children are all regularly visited by the School Medical Officer. The curriculum followed is that of the ordinary Public Elementary School, modified to meet the needs of these delicate children. ’

Four years later, we read in the annual report that: ‘The teaching in these schools is planned to provide as much individual tuition as possible, as many of the pupils are backward through non-attendance on account of ill- health, while others have made normal progress, though for a time their health demands their attendance at an open-air school. ’ Among the subjects specially mentioned as being on the curriculum of these schools were handicraft, typewriting, domestic subjects, nature study, and gardening.

During the 1920s Victoria Park was among the smallest of the handful of open-air 'park' schools in Nottingham; others included the Arboretum (the largest), Bulwell Forest, Nottingham Forest, and King Edward Park. While the Arboretum had an average daily attendance of about 114, that at Victoria Park varied between only 25 and 27 children.

1929 appears to have seen inter-committee discussion over the future of the Victoria Park Open-Air School. The Director of Education wrote in April to the Public Parks Committee, asking if they would give assent to the appropriation of the school site for educational purposes. On being asked for his advice, the Town Clerk’s reply was that the Education Committee had the right to appropriate the site, but the Parks Committee nonetheless told the education authorities that they could not agree to this proposal.

What happened next was a change of role for the school. The Victoria Park Open-Air School for Delicate Children closed in November 1929, to enable extensions to be carried out. Following this work, the school reopened after Easter 1930 as an 'open-air school for retarded children' replacing the St Catharine’s Temporary School. While the open air facilities at Victoria Park had formerly been only for physically defective children, the new buildings were to be for the sole use of children normal in health, but, in the parlance of the time, D. & B. (dull and backward.) The terms used seventy or eighty years ago to describe children with special educational needs ring uncomfortably on the modem ear. The additional classrooms erected brought the number up to four, and it was stated that the school was expected to have a capacity of 160 pupils.

VICTORIA PARK looking towards Promenade, 2004.

VICTORIA PARK looking towards Promenade, 2004.After the Second World War, the buildings were a nursery school for a number of years, but have for more than twenty years now been a Kingdom Hall of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. At this time of writing it is intended to replace the old buildings with a new Kingdom Hall, but I understand that there are likely to be objections to this plan.

One twentieth century development at Victoria Park which has caused some confusion was its designation as a King George’s Field. The associated insignia which appear on the Bath Street gateposts have led some to conclude that the park as a whole had undergone a change of name, but this is a mistaken impression. The panel on the left-hand side bears a lion, and the inscription ‘George V. AD 1910-1936;' the right-hand side displays a unicorn, and the words ‘King George’s Field.’ The King George V Playing Fields were set up as a memorial to the late King in November 1936. As defined by the Trust, a playing field was ‘any open space used for the purpose of outdoor games.'

It came as something of a surprise to find that Nottingham did not seek this status for Victoria Park until October 1956, in respect of ‘A piece of land having an area of two thousand square yards or thereabouts situate near the southern boundary of Victoria Park... and proposed to be developed for use as a children’s playground with the construction thereon of a shelter, netball pitch and playground apparatus.’ The 1956-57 annual report of the Public Parks Committee duly reported that funds had been received from the King George V Playing Fields Association ‘to lay out an equipped playground with a suitable shelter.’ This shelter is no longer to be seen.

PROMENADE from Victoria Park.

PROMENADE from Victoria Park.I said earlier that not much had changed at Victoria Park since the end of the nineteenth century. We already know, however, that the park has been given a Green Flag Award for 2004 - one of four in Nottingham - so something has indeed changed here lately, and for the better.

First it should be explained what a Green Flag Award is. This scheme recognizes and encourages good standards in parks and green spaces. Although independently run, it has backing from the Government and from the Countryside Agency. English Heritage, and other bodies, and entry for an award is through the Civic Trust. Launched in 1996, it made its first awards a year later. The award aims to recognize the diversity and qualities of urban and countryside parks, and the value of green spaces to those who use them. To quote from its brochure: 'Many places that were run-down and neglected just a few years ago are, today, exemplars of good park management.’ As an interested and sympathetic layman, I can say only that my recent visits to Victoria Park, in 2004 and in the early part of 2005, have confirmed this observation.

PART OF THE PARK in 2004, showing one of specially designed benches and litter bins.

PART OF THE PARK in 2004, showing one of specially designed benches and litter bins.The first thing the visitor today notices on entering by the main Bath Street entrance is the handsome information board, with raised metal letters. This describes the park, summarises its rules, provides useful phone numbers, and gives an outline of its history. We read that the park contains uniquely-designed benches and bins, and features a water cascade, ornamental flower and tree planting, shrub areas, children’s playground, ball court, picnic benches, wildflower meadows, and toilet block. We are further told that the main activities are strolling, children’s play, picnicking, football and basketball, and dog exercising,. A developing calendar of events is mentioned.

The basic framework of Victoria Park still exists, with areas of grass dotted with handsome mature trees; there is, however, less asphalt than there used to be. Two children’s areas are provided, railed, and with hedges in which pyracantha is prominent. Provided with a bark surface, these play areas feature slides, horses and a swing. Adjacent to one of them is a hard court with football goal and basketball net. There are more swings nearby, set on a ‘soft-landing’ surface.

A couple of picnic tables stand on the grass, and the main planted area of ornamental plants has a circular bed as centrepiece, as it did in the 1890s. Each visitor will have a particular favourite among the plants: mine include the hostas, which I found miraculously free from snail and slug damage. Among much else to enjoy can be found lavender and dark-leaved prunus, fatsia, santolina, potentilla, hebe, hemerocallis, rudbeckia and crocosmia. The litter bins and benches are, as promised, striking, as well as pleasing and functional.

Two other notices, in the same style as the main one, explain the function of the tower built as part of the Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert, and give a brief history of the adjacent St Mary’s Rest Garden.

THE WATER CASCADE in 2004. The headstone has been brought in from the Rest Garden, next door.

THE WATER CASCADE in 2004. The headstone has been brought in from the Rest Garden, next door.It is a pity that the attractive little water cascade has to be behind locked railings (though one understands why this is necessary,) and the lavatories also appear to be usually locked. These inescapable precautions apart, one’s only disappointment is that nowhere on site is the well-merited Green Flag award explained.

Each time I have visited the park, there has been an encouragingly small amount of litter lying about, but a surprisingly sparse number of users. No doubt I went at the wrong times. The occupants of the houses in Promenade, of Park View flats, and of the apartments in the former Bancroft’s Factory overlooking it, are very fortunate to have such a pleasant open space on their doorsteps. Those responsible for its daily care deserve our thanks.

As I recently wrote elsewhere, it was a real pleasure to talk with the groundsman cutting the grass in the old burial ground next door, and to learn from him that a wildflower meadow was to be created there. When he mentioned that he took an interest in local history, and was familiar with the relevant websites, I felt that the place was in excellent hands.

This account of Victoria Park was completed in the spring of 2005. If, as seems likely, further developments occur in the near future, they will be reported in the magazine.

The second part of this article will, as mentioned earlier, deal with the old burial ground, now St Mary’s Rest Garden, whose history is absorbing and quite complicated.

(To be continued in the next issue)

1. A full list of footnotes will be included at the end of Part Two.

< Previous