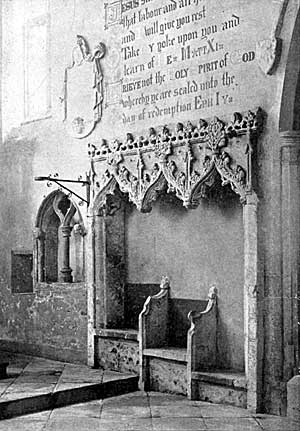

Sedilia at Laxton.

The chancel bears evidence of having been re-built in the early Perpendicular Period, say about 1400, and of the arcades, at least a century earlier, being left untouched, and re-used. The arches in the aisles were probably narrowed at the late restoration, their first pointed character not being original. The south chapel was the burial place of the chief or superior lords of the manor, holding of the King, the Everinghams, a family descending from the Norman Alselins, and one of great power and wealth, endowed with the hereditary custodianship of the royal forests of Notts. and Derbyshire, down to the close of the thirteenth century. Their importance, and that of their Anglo-Saxon or old English predecessors, is no doubt indicated by the large earthworks (the largest in the county), situate in the “Old Hall Grounds,” some quarter of a mile distant from the north of the church. The north chapel was the burial place of the secondary, or inferior lords of Laxton, who obtained their name from the place, and who rose to great wealth and importance as the Lords Laxington. Sir John, Lord Laxington, was Lord Keeper of the Great Seal to Henry HI.; and, before his death, in 1257, he founded a chantry here, dedicated to St. Mary, and gave it to the Abbot and Convent of Rufford, ‘to pray for the souls of his ancestors here buried. This Lexington family purchased the the manor of Tuxford, and was succeeded by the Lungvillers and Bekerings, whose arms are carved on the outer eastern face of the substitute for their chapel. These later families became connected with the church by marriages with heiresses about 1272.

The eastern portion of the chancel is highly decorated. On the north side is an Easter sepulchre with an aumbry in its recess; on the south side a richly designed, three-seated sedilia minus a number of shields, and a double piscina; east of the latter, and in a line with the altar, is a low side window, a somewhat remarkable feature in this position; above, and also in the south wall is a tall, narrow, transomed window of graceful form, with a corresponding one, similar, but not identical, in the north wall. The east window is wholly modern, the former one was lower in the sill, but otherwise all record of it is lost.

Figure of Bishop Rotherham, Laxton.

My descriptions of most of the details of this formerly important church, are but reflections of the light thrown upon it by members of the Thoroton Society. Especially the iron hook and sheath pulley fixed in the western spandril of the sedilia, which has long been a puzzle, but is now proved to be part of the machinery for the working of the Lenten Veil, dating from the 15th century—a feature believed to be unique in the county.1 The identification of the figure of Archbishop Rotherham, and his intimate association with the fabric, originates with Mr. T. M. Blagg, and has had a flood of light thrown upon it by Canon Leigh-Bennett’s life of the Archbishop.

Though much has been “restored” out of sight and knowledge, we must yet be thankful that so much of interest remains, and that we can look at the redeeming portions of the modern work of 1860, namely the sculpture in stone of heads and foliage, which is the work of an able artist from Lincoln.

There are six bells in the tower. One inscribed

“Benedicta sit scn (Sancta) Trinitas,” is possibly mediaeval, or has come down to us from Archbishop Rotherham’s time. It has a maker’s mark, which looks like an evil monster at work at a forge.

Two are Elizabethan, dated respectively 1591 and 1599. They each bear the arms of France and England, quarterly with lion and dragon as supporters. The former has the inscription “GOD SAVE OUR QUEEN,” the latter “GOD SAVE OUR CHURCH, OUR QUEEN, OUR REALME, AND SEND US PEACE IN GOD. AMEN.” These inscriptions are in Roman capitals, and one has a maker’s mark, difficult to describe without a rubbing, but in which a cross and a crescent moon and a rayed sun are prominent.2

Another is “Jacobean, dated MDCXXI., inscribed, “GOD WILL REWARD MY BENEFACTORS.”

Two more are modern, one a gift from the Martin family. The other, cast by Jno. Warner & Sons, London, in 1860, records the date of the restoration, or rather rebuilding of; the greater portion of the church, the internal part alone being now original.

The above account was followed by a carefully prepared paper on the effigies and tombs, by Mr. W. Stevenson, of Hull, which will be found in the Supplement of this number of the Society’s Transactions.

It is to be regretted that the interesting heraldic glass, mentioned as existing in the church at Laxton, in the days of Dr. Thoroton, should have been lost or improved away.

The following arms, however, still survive,

appearing untinctured in two places in the oak roof of the nave. There is some conflict among authorities as regards the colour of the field of the arms of this family. Guillim says “ the field is ruby, three water bouget pearl . . . ;” and Burke, in his “Dormant and Extinct Peerages,” confirms this description; but in Papworth’s “Armorials” (p. 346) they are described as “Azure, three water bougets or.” Dr. Thoroton abstains from committing himself to either rendering, but in his plate of arms they are shown in accordance with the two first authorities.

These arms now exist in a mutilated form on the shield of the effigy of the man on the triple tomb, where the lion is carved in relief, and gives no indication of the tinctures.

It seems to be generally admitted that the field of the arms of Everingham was gules, but the tincture of the lion is diversely described. Dr. Thoroton, in his plate of arms, shows the Everingham lion as vair. A. E. Lawson Lowe, in his “Notts. Armoury” (vide “The Reliquary,” vol. xvi., p. 107) gives vair the preference. In Burke’s “Armoury” the same, with the addition that the lion is crowned or. In such an old authority as” Parliamentary Writs,” vol. I, p. 411, is a table of arms borne by knights, temp. Edward I., where the following appears:—“Sire Adam de Everingham, de goules a un lion rampaund de veer;” but some “tricking” by the Heralds College, in the possession of the Vicar, of the arms which at one time appeared in this church, shows the lion to be charged as checquey in every case, and there seems to be some reason for thinking that it was thus (impaled with the arms of Hastings, of Pembroke), in the east window in former days. (Vide Thoroton.)

This shield is carved in stone on the outside of the east end of the north aisle. It is a modern restoration of what existed previously. Dr. Thoroton remarks, under Shelford, p. 148, “This family of Stanhope before used the coat of Longvillers for their paternal coat, as in Tuxford, Newstead, and other places may be observed.” Strelley is one of the other places.

This shield appears near the above arms of Longvillers in the east window of the north chapel, and is described by Thoroton as “a chequey with a Bendlett,” but most (if not all) other authorities, use the term “bend.”

It will be noticed that there are no armorials of the Lexingtons now remaining in this church.

Laxton, it will be seen, was the “Mecca” of this excursion, and hence the large share of notice accorded to it, but, being a place replete with interest, this isolated parish can only be regarded as partially exhausted by such a brief inspection as was possible on the occasion of this, the first visit of the Thoroton Society.

(1) This may be detected in the illustration as a projection

on the right hand top corner of the sedilia, just under the cornice, and

between the crocket and the pinnacle.

(2) Clearly founded by one of the Oldfields—the second Henry or George—J.S.