Bulwell Free School.

During the next fifty years, several brick houses were built, all very much after the same design. Perhaps the most perfect specimen remaining, and certainly the best for the purpose of illustration, is an old house in Quarry Road, Bulwell. It has ‘the characteristic “shaped” gables, quoins, and dentilled string courses, and notwithstanding ‘its present sordid surroundings, it still retains a distinguished and picturesque appearance. The bricks are irregular in size–about 10ins. long x 21/2ins. thick–the usual hand-made, clamp-burnt bricks of the period, laid in irregular bond, with wide mortar joints. Above the open porch is a carved stone panel, containing a central shield surmounted by mantling and crest, with a space for the date beneath, and a smaller shield in each of the four corners. The crest is the well-known Saracen’s head of the Strelleys, and on the upper dexter shield there are traces of what appears to be Paly of six for Strelley. On the upper sinister shield the arms of Sacheverell, on a Saltire five water bougets are plainly visible. The remainder of the heraldry is now worn beyond recognition. A workman who repaired the building in 1900 has stated that the date 1667 was then legible on the date-stone.

I learn from a Deed of Trust, dated 1669, that this fine specimen of early brickwork, now occupied as a dwelling and known as “Strelley House,” was “built in the Parish of Bulwell in the County of Nottingham by George Strelley, late of Hemshill in the said County, esquire; for the educating and teaching young children of the Inhabitants of the said Parish.”

“The Honble William Byron of Bulwell Wood in the County of Nottingham, Esqre. was appointed Governor and Richard Slater of Nuthall in the said County, Esqre, Daniel Chadwick, Minister of the Parish of Bulwell, William Strelley of Arnold & Edward Clud of Northwell Park in the said County to be his Assistants.” These were appointed to meet at the school-house at least once in each year, and “for their accomodation at their General Meeting there shall be allowance of 6/8 to be spent in Ales & Cakes yearly on the first day of November, which charge to be borne by the said Schoolmaster out of revenue settled upon the School.”

Bulwell Free School, Nottingham.

James Wylde was appointed to be the schoolmaster, and he was to take not more than thirty children. of the parish of seven years old and upward, and instruct them in the “Latin tongue,” and “likewise to write & read written hand and to Cypher and cast acompts (that is to say) to be taught Arithmetick untill they shall attain the first 5 rules therein,” and “such of his Scholars as are capable of learning, & willing to learn, and to be taught, he shall use them mildly & with gentleness, & those that are perverse, & stubborn, & not, willing to be taught, to such the master is to give due correction with the rod, for the quickening on to learning.”

By an Order in Council, 12 December, 1885, a scheme was approved whereby this school was discontinued, and the building was directed to be sold, and out of the proceeds scholarships were instituted, to be known hereafter as the “George Strelley Endowment.”

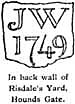

If the nobleman could display an achievement of arms on the buildings he erected, the poorer man could and did perpetuate his identity in a simpler manner. Almost every house that was built at this time, no matter how small or humble, had a panel built into the wall displaying initials and date–often the initials of husband and wife–and the date of the memorable year that saw their building completed. As a general rule they are lozenge or diamond-shaped stone panels, but I find that at least one of our local examples is made of iron, due no doubt to the fact that stone was scarce in this district.

Although these panels are very simple in design, they are very effective in appearance and invaluable as records, and it is a pity that so many of them have been removed. I think I am correct in stating that only seven examples that have any claim to antiquity now remain in Nottingham.

Owing to the vigilance of one of our members, the old brick house in Sussex Street (Turncalf Alley), next door to the “Chelsea Pensioner,” although repaired and covered externally with stucco, still retains the date panel put in by the original builder.

|

|

The Borough Records contain references to a William Petty, who was a Bridgmaster in 1656, and an Alderman of the town in 1682, and it seems very possible that it was he who built this house by the side of the footpath leading to the Trent Bridge, whither his business took him.

|

The “White Horse”, at Radford, is another characteristic example. Here again the old brickwork has been covered with stucco and whitewash, but the shaped gables, the heavy dentil string courses and pediments are unmistakable, and the date of erection is recorded on a beautiful panel of the usual type, built into the front wall, just below the eaves. Perhaps the most interesting bit of early brickwork remaining is in Castle Gate, on the west side of St. Nicholas’ Rectory. The house once stood back from the street line with a garden or forecourt, which has since been built upon, thus hiding to some extent the shaped gable and the beautiful old brickwork, but a peep down the passage will reveal the “cut and rubbed” work in the cornice, and the pilasters, which are worthy of more than passing notice. A very interesting date-stone is fixed high up in the west wall.

|

In the brick chimney stack on the north side of the old building in Friar Yard, that once formed part of the Carmelite Friary, there is a square stone panel, containing the initials of John Manners, husband of the celebrated Dorothy Vernon, who converted the premises into a dwelling house for his own occupation.

Three other date-stones are all that remain to complete the list.

|

|

|

Two old houses that deserve passing mention, as the “Sawyer’s Arms”, in Lister Gate, and the “Hearty Good Fellow,” in Mount Street, but in both cases, owing to recent renovation, only a very small portion of the original work remains.

Old house, Castlegate.

During the reign of Charles I. (1625-1649), an Act was passed to regulate the size of bricks. Hitherto the bricks made in this country were of various sizes and colors, and sometimes they were turned out in large blocks of ornamental shape, more like our modern terracotta. Henceforward they were to be uniform in size, and a heavy tax was imposed upon all bricks, made for sale in this country.

The following is the text of a Proclamation made by the King, 2 May, 1625, and, although it expressly mentions only the City of London, it was made to apply to other parts of England:

By the King. A Proclamation concerning Buildings, and Inmates, within the Citie of London, and confines of the same.

“That in the moulding of the said Brickes, the moulds be throughly and well filled, and not set in the moulds, in the laying downe; And that they be sufficiently and well dried before they be put into the Kilne, and then carefully and throughly burned; So as for the assize, every Bricke being burned, conteine in length, nine inches, in breadth, foure inches one quarter and halfe a quarter of an inch, and in thicknesse, two inches and one quarter of an inch.”

The bricks were made by hand, in wooden boxes or moulds, and, after being partly dried in the sun, they were burned in clamps—i.e., pyramidal stacks of raw bricks with a fire burning inside. Being made of unwashed clay and sand, the bricks came out with a very uneven face, but of a fairly uniform color; save that in the course of burning, the ends of some of the bricks came into contact with the fire and were partly vitrified, and so became much darker in color. These were picked out and utilized to form the diaper patterns so often seen in old brickwork.

St Peter's Street, Old Radford.

The "White Horse", Old Radford.

There is an example of this in an old house in St. Peter’s Street, Old Radford. The pattern is considerably marred by the insertion of three modern sash windows, but sufficient of it remains to give the effect. This house was at one time used as the Peverel Prison—presumably when the Court was temporarily removed from Lenton in 1842, and there are people still living who can remember the time when prisoners were kept there. Mr. James Granger can distinctly recollect conversing with a man whilst imprisoned there for a debt contracted with the late Alderman Fowler. This man was allowed to keep his stocking frame on the premises, and to walk out as far as the Market Place on Saturday nights, the rigours of the Basford and Lenton prisons of olden days being considerably relaxed by this time. The building on the opposite side of the road was formerly the old workhouse. It has since been converted into a block of cottages, but still wears a plain official aspect: a contrast with the old workhouse building of St. Nicholas’ parish on Castle Road (formerly called Gillyflower Hill), which is also converted into dwellings (Jessamine Cottages), and forms one of the most picturesque groups of brick building within the city. The old brick houses at the foot of the Castle Rock, in Brewhouse Yard (illustrated in Transactions, Vol. VIII.), give another interesting picture of the brick architecture of past days.