Jessamine Cottages, Castlegate.

Improvements in the manufacture of bricks soon began to be made, and it would be an interesting study for anyone to compare the brickwork of any of the foregoing examples with the gate piers and the front wall of the Hon. Rothwell Willoughby’s house on Low Pavement (A.D. 1730-1740), and again with the “rubbed and gauged” portion of a house 29, High Pavement (opposite the County Hall), admitted to be the finest specimen of brickwork ever executed in Nottingham (A.D. 1820). The bricks, in this case, were made of washed and prepared clay and sand placed in moulds lined with metal,— copper or brass—and burnt in a kiln. Each brick would then be rubbed on a stone until it was reduced to the exact size or “gauge,” and its face made absolutely true.

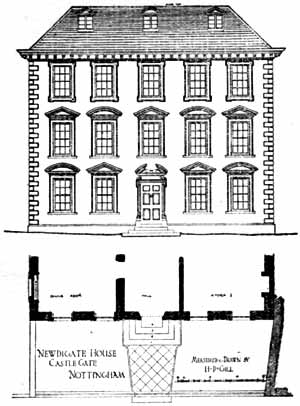

Newdigate House, Castlegate, Nottingham.

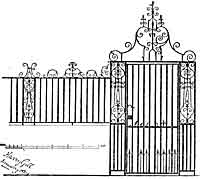

A house of a totally different type from any of those already mentioned (Newdigate House), stands on the north side of Castle Gate. It may be taken as a typical specimen of the houses built in the town during the reign of Charles II. I have not been able to find any documentary evidence to confirm the date of erection of this house, but judging by the style of it, and comparing it with other buildings that are dated, I should say it was built circa 1675. It is frequently referred to as Marshal Tallard’s house, from the fact that he lived there during the time of his captivity, after his defeat by the Duke of Marlborough at the battle of Blenheim, August 13th, 1704 (August 2nd old style). The façade is symmetrical, the outer walls are encased with stucco, and all the window and door openings are emphasized with heavy classical architraves and pediments in the same material. Instead of picturesque gables there is a horizontal cornice of bold projection, supported on oak brackets, carved into the acanthus leaf pattern, with molded and panelled soffits between. In front of the house is a low fence wall surmounted by a wrought iron railing of elegant design.

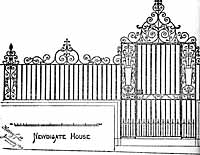

The mansions of this period were frequently adorned with wrought iron work, and it has been thought advisable to illustrate a few of the best examples remaining, as they are fast disappearing. A few words on the rise of this beautiful art may not be out of place.

Newdigate House.

Ever since the days when Thomas de Leighton fashioned the beautiful grille of wrought iron for the tomb of Queen Eleanor at Westminster, A.D. 1292, ironwork had been growing in favour as a decorative material. At first its use was restricted to such minor parts as the hands of clocks, weather vanes, hinges, and gratings, or “vizzylings,” as they were called in the Middle Ages. The art progressed through the 14th and 15th centuries, and as the need for plate armour declined, the smiths seem to have turned their attention more and more to decorative work, until it reached a high state of perfection in the 16th and 17th centuries, when we find elaborate examples in screens and entrance gates, .&c.

Low Pavement (Vault Hall.)

In 1693, Jean Tigou, a Frenchman, who has executed many important works in this country, published a “New book of Drawings” shewing a series of designs for wrought ironwork, but the English smiths’ work was not much affected by it. The broad effects he aimed at were not legitimate, as iron bars could not be hammered out to form such large leaves and “husks.” These were beaten out of thin sheets of metal (copper was sometimes used), and rivetted or brazed on to the bar work—not real smiths’ work but repoussé—and not calculated to endure in a climate like ours. The celebrated screens from Hampton Court, at one time exhibited in the Castle Museum as the work of a local smith, are now admitted to be fair examples of Tigou’s work. Huntington Shaw (born in Nottingham, June 26th, 1660, died at Hampton Court, October 20th, 1710), may have executed some of the work on these screens, but he was not responsible for the design. There is a popular supposition in Nottingham that all the best examples of ironwork are by Huntington Shaw, but that supposition cannot be maintained. In my opinion, it is doubtful if there is a single specimen of his work in the city.

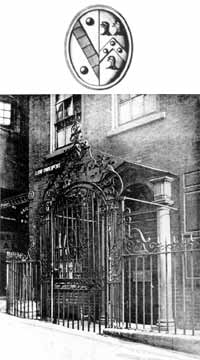

The finest example of ironwork remaining in situ is the railing and gate in front of a house on Low Pavement, at the corner of Drury Hill, formerly known as “Vault Hall.” This name was derived from the room or vaults beneath, where the ejected ministers, Whitlocke and Reynolds, used to hold their clandestine meetings.

26, Hounds Gate.

The house was enlarged and partly rebuilt in 1733 by Mr. Gawthern, who purchased it from William Drury, grandson of Alderman Drury (who caused the name to be changed from Vault Lane to Drury Hill). There is a spout head at the rear dated 1792, but that belongs to a later addition. The drawing-room decorations are said to be by the celebrated Brothers Adam. The iron railing and gates, together with that in front of Willoughby House, make a continuous length of about fifty yards, and are quite a striking feature of the Low Pavement. The scroll work above the gate supports an oval frame containing a coat of arms in repoussé work on both sides. Argent, a bend compony gules and azure between two pellets, Gawthern; impaling Or, on a chevron between three lions jambs erect sable, as many plates, Austen. This is the only specimen of ironwork in Nottingham that carries armorial bearings. At the southern extremity of the property in Broad Marsh there are two heads to the down spouts, in cast lead, having the initials F G and the Gawthern crest out of a mural coronet, or, a wyvern’s head, sable:

There is a railing very similar to the last in design and workmanship in front of 26 Hounds Gate.

Basford Hall.

Comparing the three foregoing examples with other work up and down the county, I should fix the date of their execution circa A.D. 1700; but while all these are very good specimens in their way, there is nothing about them to lead us to suppose that the smiths of Nottingham were better workmen to those of any ‘other town.

Another pleasing example of the same type of work, but perhaps later in point of time, is the gate to Basford House (opposite the church at Old Basford), and this illustration is rendered the more interesting because it was in this house that Philip James Bailey wrote his “Festus.”

The gates at ‘the entrance to Watnall Hall are a very fine specimen of smiths’ work, and worthy of inspection. (This illustration was kindly lent by Baron von Hube, and originally appeared in his book on the History of Greasley.)

Entrance gates, Watnall Hall.

Entrance gates, Watnall Hall.In the Castle Museum there are several exhibits of local wrought ironwork of great interest, notably the gates from Colwick Hall, dated 1776, and several brackets and signs, etc. When the time comes for their removal it is to be hoped that the Castle collection will be further enriched by the examples illustrated in this paper.

In the early days of wrought ironwork, the smith was the designer as well as the craftsman, and then the most artistic work was produced. During the reigns of Elizabeth and James, we can see that the design was beginning to be influenced by the whims of the builder and the decorator; towards the end of the 18th century, the influence of the smith can scarcely be seen at all, and wrought ironwork was rapidly losing all its characteristics. When the style introduced by the Brothers Adam came into general use, attempts were made to give a lighter and more elegant appearance to every branch of the building work, and wrought ironwork suffered in consequence, for at this period lead was sometimes substituted for the finer scroll work Even at its best, wrought ironwork is not a very suitable material for out-door work in our climate, for wherever it comes into contact with the damp it begins to corrode and perish. This led to the introduction of a more lasting, but far less artistic material—cast iron, and the individuality of the craftsman in hammered ironwork gradually passed away.