The statues that once stood upon these brackets were destroyed ages ago. The one on the north side would probably be a representation of one of the missionary bishops, St. Paulinus or St. Aidan; the one on the south side would surely be St. Swithun, for it was incumbent on the parishioners at the time to provide “the principal image in the chancel of the saint in whose honor the church is dedicated” (1305-1368), and this is one of the three churches in Nottinghamshire dedicated to the weather saint.

This statement is corroborated by the list of wills in the Torre MS. at York. “10th August 1534. John Shirley of Wodborowe” willed that “his body to be buried in the chancel of Wodborowe before S Swithin.” 13th Nov. 1558. Henry Shirley of Woodborowe, “his body to be buried in the close of S. Swithin's in Wodborowe upon the south side of ye chancell.”

St. Swithun, Prior and afterwards Bishop of Winchester, died July 2nd, 862, and was buried, at his own request, “in the churchyard, where passers by might tread on his grave and where the rain from the eaves might fall on it.” In 971 his body was translated to a gilded shrine within the church, but not until after the operations had been delayed for forty days by incessant rain, as a protest against the violation of the good bishop's wishes. The saint’s day, July 15th, is still considered ominous.

“St. Swithun's day if thou dost rain, for 40 days it will remain.

St. Swithun's day if thou be fair, for 40 days ‘twill rain na mair.”

The sedilia, on the south side, framed within the returns of a heavy cill moulding, although modern in appearance, is actually contemporary with the rest of the work. It cannot be looked upon as a successful design. The decline from absolute perfection, which is just apparent in the great east window, is more pronounced in the treatment of the sedilia. Comparing the mechanical work here with the beautiful sedilias at Heckington, Hawton, and other churches of the same type, we cannot fail to notice that the decadence of Gothic architecture, so noticeable all over the country after the visitation of the “black death,” had already commenced.

The piscina is treated in a very unusual manner, having a short filleted shaft with cap and base mouldings that correspond with the respond of the chancel arch. Opposite the sedilia is a plain square aumbry (now fitted with a new door), a very poor substitute for the glorious Easter sepulchres that adorn the earlier churches built by this school.

In a list of duties for parish clerks, 1462, instructions are given "to cover the altar and rood with lentyn cloths & to hang the vail in the choir," and frequent references are found concerning "the veil which in Lent hangeth between the choir and the sight of the people" (Lyndwood). The iron hooks, to which this veil was fastened, may still be seen on both sides of the chancel, just above the altar rail.

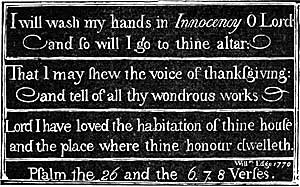

While I have much sympathy with the rector who recently protested against "the abominable tablets plastered like blisters and blackheads over the walls of churches," I would nevertheless like to draw your attention to a mural tablet on the north side, both with regard to the beauty of the script and the appropriateness of the quotation :—

It is worthy of note that this tablet was put up in 1770— a time of terrible apathy and exclusiveness—not by a priest, but by a layman, William Edge, the churchwarden, whose agitation resulted in the settlement of the first resident vicar in Woodborough.

All traces of the oak screen and the stone base upon which it stood have been removed. It is said to have been " like the one at Lambley but having more work in it," but this description is not very helpful, for the screen at Lambley is now but a relic of its former state. For many years two paper garlands, in memory of two young girls, hung upon the screen.

The choir stalls, pulpit, and western screen are quite modern. They were designed and executed by the late Mansfield Parkyns, assisted by a local joiner, Richard Ward, for many years a churchwarden, and they were presented on Christmas Eve, 1893, as recorded on the brass tablet attached to the seat near the pulpit.

The nave requires very little description. Alas 1 that well begun is only half done. The chancel must have been completed before the nave was commenced. This is clearly indicated by the fact that the western buttresses of the chancel form the east end of the aisles, and the weatherings of the buttresses can be clearly seen both inside and outside. The arcade, of three bays, is fairly good. I think the original intention was to have five bays, for if you look on the south side of the south-west pier, you will see the spring of the arch as though it was intended to carry on the arcade further westwards. The nave roof is constructed in a very elementary manner, apparently with a view to economy, for the main timbers had evidently been used before, probably in the old Norman roof.

The clerestory windows are very poor—three on the south side and two on the north side—placed without any regard to design or symmetry, and the aisle windows are even worse, for no two of them are of the same size. The tracery was added in 1891.

The south door is of the same date as the north arcade, but the porch was added at a later period. The small square western tower is a very poor specimen of architecture. It was built during the reign of Queen Mary (1553-1558). It contains four bells, cast by Henry Oldfield, of Nottingham, early in the 17th century.

We must not leave the church without noticing the font, by the south door. Although it looks so very new, it is actually the font belonging to the Norman church. It is made out of a single block of white Mansfield stone. I made a sketch of it in 1873, when it stood " on a round pillar in the form of a stilton cheese." The oak cover is quite modern (1846). At one time this font stood in the chancel near the altar rails. (Baptism was administered in the vicarage at that time.) Near to the font is the old parish chest, with three locks, one each for the vicar and wardens.

At the Restoration of the monarchy, a new altar-table was presented to the church by John, son and heir of Robert Wood, of Lambley, Recorder of Newark. This table now stands in the south aisle. It has five bulbous legs, characteristic of the period, and a carved Latin inscription continued on all the four sides, as follows: "Sacro usui me dedit Johannes, filius et heres Roberti Woode de Lambley armigeri, qui Johannes fuit Recordator de Newarke, unus custodum pacis comitatus et Viridarius Forests de Sherwood, soli Deo Fretus. Qui secum considerat quam vana et instabilis est potestas, is nihil timebit. Deum time et eum ama ut ameris ab eo. Amabis Deum si imitaberis eum, in hoc autem omnibus vel prodesse et nulli nocere. Eripe me inimicis meis Domine. Ad te confugi."

A silver chalice, with lid, and a silver paten (Charles II. hall-mark) were given at about the same time.

The registers begin with baptisms, 1547-1555, and then there is a gap to 1577. Burials do not begin until 1572, and weddings until 1573.

There are no monuments of special note. A 12th century sepulchral slab with incised cross has been used for the door-stone to the porch, and another lies near the chancel arch. A monumental slab near the pulpit, to the memory of William Alvey, has been broken, but John Alvey has, apparently, tried to make good the damage by carving the date 1681 on the chancel wall.

Just a few words about the exterior. The cross on the eastern gable has a sculptured representation of the Crucifixion on one side, and the Virgin and Child, attended by SS. Catherine and Margaret, on the other. This cross was restored in 1891, but it is an exact reproduction of the original. A similar cross adorns the west gable, but without the attendant angels. I know of only one other instance of a sculptured gable cross in this county, and that is at Clifton. There is a beautiful little triangular window in the apex of the gable, and immediately below it two shields are suspended, bearing paly of six for Strelley, the sinister shield being differenced for Strelley of Woodborough, with "a great cinque-foyle," as Thoroton calls it. If you look carefully you will see that this cinquefoil is made with six petals instead of five. I have frequently noticed a similar error in work of this period, and I can only attribute it to lack of heraldic knowledge on the part of the mason, or to the well-known fact that it is easier to divide a circle into six parts than five.

The buttresses are very effective, having bold weatherings and gabled terminations, with grotesque heads on either side. These carvings are worthy of special study. They are generally said to be typical of the expulsion of evil spirits from the church, but I have an idea that in this case they were intended to represent the sufferings caused by tha terrible sickness, the " black death," which decimated the country (1349), only a few years before this chancel was built.

As you pass along by the south side your attention will surely be drawn to the initials, dates, and diagrams that have been scratched on the wall-stones. The earliest date I have noticed is 1661. The circular diagrams were used as sundials, a movable gnomon being inserted in the hole in the centre of the dial.

But older and more interesting than dates or diagrams, are to be seen a number of curious, vertical grooves that have given rise to much comment. We noticed them at East Leake and Costock, and they are to be found at Lambley, and, in fact, on the south wall of the churches that were built before the introduction of gunpowder, in all parts of the country, and especially where the stone is of a fine smooth grain. Some say they are caused by the school children sharpening their slate pencils, but they are generally too high up for that. Others say they were caused by the sexton sharpening his pick, but I am assured that the sexton would never attempt to sharpen a hardened pick on a soft stone, he would go to the village blacksmith to have it " drawn " in the usual way. Besides, they are only found on the south side. The most popular theory is that they were caused by the sharpening of arrows, a reminder of the days when archery was the first line of attack, and when the youths were required to practise shooting on the south, side of the churchyard on Sunday afternoons.

It is no unusual thing to find that when a church was rebuilt in the Decorated period, the only portions of the old church deemed worthy of preservation were the font and the main entrance. It was so in this case. On the north side there is a doorway, built in, not for use, but for preservation. Like the font, it belongs to the Norman church of circa 1150. It has triple shafts with cushion caps and moulded bases, arid an arch moulding of three orders, containing varieties of the well-known Norman mouldings, the cable, the cone* and the chevron.

In the year 1887, the bishop of the diocese visited this church and described it as "a ruin," and its deplorable condition justified the term. During the incumbency of the Rev. F. G. Slight (1891), building was begun under Messrs. Naylor & Sale, of Derby, and the church thoroughly restored.