Piazza, Long Row, Nottingham.

A house on Long Row (No. 18) was evidently designed by the same hand, and built by the same craftsmen, for the details are alike in every respect; save that a peculiar feature was introduced in the central window of the first storey, where the pediment is supported on twisted columns having Corinthian capitals. This was a favourite Jacobean conceit, of which the south porch of St. Mary’s, at Oxford, designed and executed by Nicholas Stone, is a well-known example. The house is now denuded of its most prominent feature, the overhanging eaves-cornice. This was removed in March, igo6, by order of the Corporation, owing to its decayed and dangerous condition. The cornice was a very fine piece of workmanship. The modillions were hewn out of solid blocks of oak, the carving being apparently roughed out with the chisel, smoothed over with stucco, and thickly coated with paint. The exposed portions of the wood were found to be perfectly sound and good, but decay had set in wherever it had been in contact with the walls.

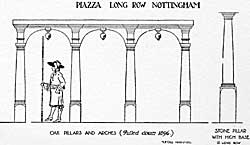

It is interesting to note in passing that the piazza of this house is the only place on the Row where columns with high bases remain, but whereas all the original ones were said to be oak posts set up on square stone bases to avoid contact with the damp ground, these are yellow Mansfield stone throughout. Two columns in the centre of the façade have been dressed down in recent years, but the two outer ones retain the original pattern.

There is an original oak pillar with a high base in situ on Cheapside, near the Shambles. It is partly hidden behind a larger column, and might easily pass unnoticed. It appears to be a surviving remnant of a Jacobean colonnade of oak pillars and arches, similar in design to the one removed from Long Row and preserved in the Castle Museum.

Thirty years ago a house very similar in its details to the one described, but having a wider frontage (five windows instead of three) was standing on South Parade. It was pulled down in 1878, to clear the site for Smiths’ Bank.

Overhanging cornices soon gave place to parapet walls of plain brickwork; but whether the change was due to apprehension of decay, or to the growing scarcity of oak, I know not.

Willoughby House, Low Pavement.

“The beautiful and well finished house” on Low Pavement built (1730-40) by Rothwell Willoughby, third son of Thomas Willoughby, of Wollaton; and Bromley House,1 on Angel Row, built (1752) are good examples of the mid-century style; but it will be noticed that whereas the earlier houses give an impression of stateliness, and refined detail, the absence of the boldly carved cornice and the paucity of stonework cause the later work by contrast to look spiritless, insipid and thin. The contrast is in appearance only, for the walls of these later houses are substantial in thickness, and very well built; the roofs are well timbered and covered with thick hand-made tiles; and there is a prodigal use of lead in the wide gutters behind the parapets, and on the valleys and hips. Easy access to the roofs was always provided, as the view from the parapet was a consideration.

The internal fittings will be referred to later ; but it may be well to mention here that at the rear of Willoughby House, there is a range of rock cellars which were said to be “the finest in the town” (Deering). The wine-cellar and the beer-cellar, on either side of a main passage, are circular on plan, and there is a large square cellar beyond. To support the ceiling each has a central shaft, having cap and base mouldings of an architectural character. The workmanship is clean and accurate, and may well be mistaken for masonry, despite the fact that it is all carved in the “living sandstone rock.”

19, Castle Gate.

During the latter half of the century, an elegant and polished style of architecture was introduced by a famous family of four talented brothers named Adam, who carried out extensive works in London and the provinces. It is a moot point whether any work was executed in Nottingham from their designs. The chimney-pieces and decorations in a house on Low Pavement have been attributed to them; and a stucco façade in St. Mary Gate, if not indeed designed by them, exhibits all the marked features of their style. A house at 19, Castle Gate (corner of Stanford Street), a large brick building with stone sparingly used—is also characteristic of their mode of treatment. In the hands of these brothers, and of Robert Adam especially, the windows always received careful consideration and treatment. An effect of size and importance was often given, as in this instance, by placing a “Venetian window” in the centre of the fenestration—i.e., three windows, having a fanlight above, enclosed within a sunken arch. An attempt was made to lighten the appearance of the parapet wall above the classic frieze and cornice, by placing at intervals a series of stone or stucco balusters in open panels; and this treatment was repeated as an ornamental string course, beneath the first floor window cills. But perhaps the most noteworthy feature in this façade is the portico, and especially the carving on the frieze, which consists of an ox-skull hung amidst garlands and flowers. The explanation is not far to seek. It was the custom in ancient Rome for altars to be decorated in a temporary manner with the skulls of slain animals set as trophies amidst garlands of flowers. The Italian architects of the Renaissance, Vignola and others, embodied this temporary form of decoration in their rendering of the Orders of Roman Architecture, and the English architects of the Georgian era were content to make a slavish copy for the adornment of houses and other buildings, in which such a design became incongruous.

There is reason to suppose that this fine building was originally the town-house of the illustrious family of Howe of Langar. Lord Howe represented Nottingham in Parliament at the time of the Revolution, and several members of the family held the seat in succession. The house is a spacious one and exhibits in the interior, even more than in the exterior, the influence of the Adams style of treatment.

Of this band of four brothers, Robert Adam (1728-1792) was the leading light and most indefatiguable worker. For forty years he was engaged in making designs for buildings and decorations. Stone, as a building material, was too heavy for his delicate treatment, and so the decorative features were executed in stucco—a secret concoction made up of powdered marble, pitch, oil, and other ingredients, the invention of a Swiss clergyman named Liardet, which, when properly executed, became harder and sharper with every year, and was scarcely distinguishable from stone. Whether we admire the Adams style or not, and opinion is very divided upon it, the individuality is most marked, and the workmanship is always excellent.

It is seldom that a town-house of this period was set back more than a few feet from the street line, but the owner always took care to reserve an open space on the south or west side. If the house stood on the south side of the street and faced the north, it had a garden in the rear; but if the other way about, then a plot of land on the opposite side of the street formed the garden or “vista.” These vistas, once considered essential, have now all been put to other uses, and it is only here and there (notably in St. James’s Street and Castle Gate) that the surrounding walls and gateways remain to indicate their former purpose. This is to be regretted; because the “vista” was always a graceful adjunct of a town-house, and the walls and gateways were of charming design.

Cheapside.

Concerning the “new fronting” process recorded by Deering, one example at least remains in premises at the east end of Cheapside (Rotten Row). Prominent in the illustration thereof, a “frame building” is seen, with projecting storeys and steep gables, said to have been the town-house of the Babyngtons; and adjoining it on the east side, and in sharp contrast therewith, is a building divided into three bays with pilasters, and having a horizontal cornice and parapet of classic design. Upon examination, however, it is clear that this also was once a gabled building; but the projecting barge-boards have been taken away, the gables cut back and “hipped,” and a “parapet wall after the newest fashion” substituted.

This is a very interesting remnant of the old town; for in addition to the “frame building,” and the “new fronting with parapet walls,” the illustration shews two of the old fashioned shop-fronts with a door in the centre and a bow-window on either side. In one case, the original glass in small panes still survives; in the other, the glazing bars have been cut away and one large sheet of glass substituted. Since the removal of a similar shop front from the Long Row a few years ago, I believe these are the only original shop fronts, in the style once so prevalent, now remaining in Nottingham.2 At the extreme left of the view is seen the oak pillar with the high base before mentioned.

St Nicholas church.

Picturesque gables at rear of Castle Gate.

The public buildings of the period call for very little notice. The parish church of St. Nicholas was re-built in 1682 in a very debased style of Gothic architecture. The only point worthy of notice in regard to it is the quality of the brickwork, and the harmonious way in which it groups with contemporary buildings in the vicinity. Indeed, the brickwork in late 17th and early 18th century buildings is invariably charming. The cottages in Brewhouse Yard,3 a group of similar gables in Castle Gate, (best seen from Walnut Tree Lane), and Jessamine Cottages, on Gillyflower Hill,4 originally built in 1729 as a workhouse for the parish of St. Nicholas, and converted into cottages in 1815, are picturesque and pleasing examples of brickwork.

(1) This house was built by George Smith,

the banker. A stone in the wall on the south side of the garden is inscribed

with initials and date, G.S., 1752. George Smith, who married Mary Howe,

a granddaughter of Prince Rupert, was made a baronet in 1757. He

inherited from his father, as a wedding gift, the house and estate at East

Stoke. His son, the second baronet, assumed by sign-manual, 7th February,

1778, the name of Bromley, and by Royal license, 6th April, 1803, the name

and arms of Pauncefote.

(2) There is a small bow-window in a private house on Birch Row, Alfreton

Road.

(3) Illustrated in Transactions, Vol. VIII., 1904 (frontispiece).

(4) Illustrated

in Transactions, Vol. XL, 1907, p. 110.