|

|

| 24 Low Pavement. | 31 Castle Gate. |

In 1724, the building of the “New Change” was commenced. This was a brick building on ten stone columns and four brick pillars, designed by the mayor, Marmaduke Pennel. It was remodelled and partly rebuilt in 1814 by Edward Staveley, architect. When the piazza was enclosed and the shops brought to the front, a hope was expressed that the whole “when finished will have a very handsome appearance, and be an ornament to the Market Place, being all stuccoed and coloured to imitate stone.” The Exchange, very much as we see it to-day, was the outcome, and I will leave you to decide whether the “hope” was realized or not. It was originally intended to construct a balcony across the front, but this portion of the work was not carried out.

In 1770, the old County Hall on the Pavement gave place to the present gloomy and depressing structure. Being a place for the administration of public justice, it was deemed appropriate to carve the Fasces and Pileus— the Roman emblems of magisterial authority,—on the entablature above the four ponderous, engaged, Ionic columns; and the Royal Arms (Geo. III.) are displayed in the shaped pediment above. The original work has been repaired, and in some cases renewed, and modern additions have been made on either side, in order to keep pace with the growing demands.

A note by Deering with regard to the constables, gives at once an interesting comparison as to growth, and also a reminder of a custom now almost forgotten, although quite familiar a generation ago. “In the 18th century there were thirty constables, more than sufficient for a town of this extent, whilst too few watchmen are kept, the bare number of four, and these so remiss in their Duty, that they seldom give the Hours above twice in a night.”

The Assembly Rooms on Low Pavement—the place where ladies assembled for dancing and social intercourse on the first Tuesday in each month, and the Tradesmen’s Assembly in Gridlesmith Gate, whither the “wealthy tradesmen, their wives, sons, and daughters” repaired, are changed and gone beyond recognition. The race-course and grand-stand on the Forest, the bull-baiting rings in the Market Place are also things of the past, while the cockpits in the yards and cellars of taverns are occasionally brought to light, when excavations are being made for the foundations of picture palaces and other modern delights.

The General Hospital was founded in 1782, but practically the whole of the original buildings have been superseded by modern additions.

The external aspect of these old buildings is more or less familiar, but it is only the few who are privileged to see the internal work, wherein the chief attraction is to be found; for the craftsmanship of the joiner,— at one time restricted to upholstery and to the making of “joined” mahogany furniture,—was beginning to embrace the whole of the internal fittings in the house. This change was due to the increasing use of “firre-deales,” which were cut from coniferous trees and shipped from the Baltic ports and were beginning to take the place of English oak.

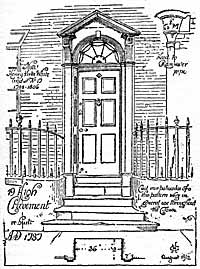

19 High Pavement, re-built 1737.

The entrance doorways were invariably narrow— many of them are not more than three feet wide—and were approached by a flight of stone steps carried over a sunk area protected by iron palisades. It is interesting to note in passing that the pattern of the palisades—the vase-topped standards and square rails with beaded and pointed heads—shew but little variation, the country through. The sunk area was made for the purpose of giving light and air to the basement; for whilst it must be said of the provincial maid of to-day, that “she always avoided anything low, with care the most punctilious,” the same cannot be said of her predecessor; as the domestic quarters in a town house of the 18th century were always placed beneath the reception rooms. Mr. Gotch has told us, that at Wollaton the domestic offices were relegated to the basement, because there was no back to the house, the design being symmetrical on all sides; and this may account for the adoption of a similar arrangement in subsequent houses.

No matter how simple the design of a doorway might be, the workmanship was good and well considered even to the smallest detail—hinges, knobs, locks, knockers—all well finished and suitable for the purpose, and a projecting pediment or hood was invariably contrived as a protection against the weather. In some instances, the supporting brackets to the hood were made of wrought-iron, in graceful scrolls with “snub” ends, but more frequently wooden consoles were used. Later in the century, probably due to the influence of the brothers Adam, figures were skilfully introduced on medallions and keyblocks, and although the subjects represented were often meaningless, the figures were gracefully modelled and well finished.

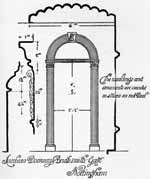

Jacobean doorway, Bridlesmith Gate.

A side entrance to a house on the western side of Bridlesmith Gate, composed of reeded pilasters and semi-circular arch, has a very fine figure study on the key block. This house is worthy of inspection, because the oak timbering across the passage is the remnant of an old frame-structure, and clearly shews to what extent the street has been encroached upon and made narrower by putting a modern shop-front in a plumb line with the overhanging upper storey of the old building.

Figure subjects were also frequently introduced in designs for door knockers; for while the lion’s head with a ring in its mouth would appear to have been the favourite design, a variety of other elegant patterns was sometimes used. (See the fine collection in the Art Museum, Nottingham Castle.)

The most distinguishing feature of the period, however, was the fanlight. In these days the term “fanlight” is applied to a light above a door, whether it be shaped like a fan or whether it be square and plain, but in the 18th century, when “every lady carried a fan, of which she made constant use, furling, opening, fluttering it ceaselessly,”—when, in fact, the lady’s fan was as indispensable as the gentleman’s silver snuff-box, the semicircular light was reasonably so-called because of its resemblance to the delicate framework of an open fan.

“The fan shall flutter in all female hands

And various fashions learn from various lands.” —T. GAY.

|

|

| 58 Castle Gate | High Pavement |

|

|

| 54 Castle Gate | 36 Castle Gate |

|

|

| Church Gate | St James' Street |

The fanlight and the sliding sash-window were contemporaneous, the one being the outcome of the other; for when casements with tiny panes of lattice-glass gave place to sashes with larger panes, a new problem presented itself, viz., how to cut up a circular table of glass to advantage; for it should be borne in mind that “blown” glass was then in vogue. A brief description of the process of manufacture may not be out of place, as it has gone out of use and almost out of remembrance; although, as recently as thirty-five years ago, it was common to see a travelling glazier, hawking in the streets for repairs, with a crate strapped on his shoulders containing semi-circular sheets of glass, the smaller ones known as “slabs,” the larger ones, containing the bullion or knot, known as “tables.”

The ingredients used for making “crown” glass— white sand, carbonate of lime, carbonate of soda, and other chemicals—were put into a crucible and heated in a furnace for forty-eight hours. After removing the dross from the surface, the liquid glass was allowed to cool down until it assumed the consistency of paste. A small quantity of this paste was then “gathered” on one end of an iron tube about five feet long, and blown by the mouth into a sphere, like a large soap bubble. The side of the sphere opposite to the blow-pipe was then flattened by contact with a hard surface, so that an iron rod, or “punty” could be attached when the blow-pipe was withdrawn. The glass attached to the “punty “—in appearance like an umbrella reversed by the wind—was heated up again in front of the furnace, and then twirled round and round on the “punty,” until it opened out and became a flat disc; when it was laid down on an iron table and placed in the annealing oven, where it was allowed to cool by slow degrees. It thus became a circular sheet of glass 48in. to 54in. in diameter, uneven in thickness and of varying colour, some parts being an agreeable green tint, others iridescent or smoky in appearance, according to the ingredients and the strength of the sulphur fumes. Each plate of glass was cut into two unequal parts, the larger one having a “bullion” or “knot” near the centre, where the “punty” had been attached. It is obvious that after cutting a certain number of comparatively large square panes out of a “table,” the bullion and the pieces with curved edges would go to waste, unless some way of using them could be found.