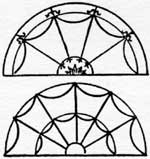

Fanlights.

The problem was solved by the introduction of the fanlight, with its graceful curves and loops. Examples may be found in every old town and village in England, and it is interesting to note the similarity, and at the same time the great variety in design; at first, they were elegant and pleasing, but later, they became clumsy and out of proportion. The bullions were considered to be abortive pieces, and were relegated to outbuildings, or to the back windows of houses. Although they were the product of a primitive method of manufacture now gone out of use, it has lately become necessary to manufacture spurious imitations in order to meet the growing demand. A genuine bullion is unmistakable, both on account of colour, and the “whirl” effect in the glass, and old crown glazing can always be identified by its smooth but uneven surface.

I have not been able to ascertain how the change from casements to sliding-sashes was brought about; it would appear to have been gradual and imperceptible and no reliable data can be found. In all probability the idea of the sliding-sash was brought from the Low Countries. It was not used in this country until the reign of Charles I. at the earliest, whilst subsequently, and especially during the reign of William III. and Queen Anne many casement windows were transformed into sash windows; for it is no unusual thing to find that in houses of the earlier date, window openings in the principal rooms were enlarged and fitted with sliding-sashes, while rooms of lesser importance retained the original casements.

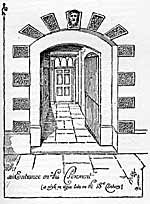

An entrance on "The Pavement" (a style in vogue late in the 18th century).

I have in my possession one of the earliest sash-pulleys used in Nottingham. It is made entirely of wood—not only the boxing but the grooved pulley also is made of wood, and I know of many sash-pulleys still in use having oak boxings and box-wood wheels. The next advance1 was the substitution of metal in place of boxwood for the pulley-wheels; the modern method is to make the whole thing entirely of metal, and in the best work the pulleys are run on ball-bearings of steel. The balance-weights were made of lead, roughly cast to suit the shape of the boxings and suspended by cords of catgut. The earliest sashes were divided into oblong panes about 12in. x 10in. with moulded glazing bars 1½in. wide. The size of lattice-panes in casements seldom exceeded 8in. x 4in.

From the Restoration onward until the reign of Queen Anne, doors were framed in two panels, technically known as “raised mitred,” from the panel, which was almost as thick as the framing, having a sunk margin all round, and a small moulding worked on the edge of the framing. Throughout the Georgian period, the fashion was to frame them in six panels, i.e., two panels in width and three panels in height. Fir was the material generally used for making doors, but occasionally (as in Lord Howe’s house) they were made of mahogany, beautiful in colour and figure. Oak as a material for doors still lingered, but strange to say, only in rooms of little importance. For instance, oak doors are found in the upper rooms only, in Willoughby House.

Internal door, 64 St James' Street.

Wood casings were used for external as well as internal openings, framed and panelled to correspond with the doors. The bolection mouldings were omitted in the lower panels of external doors and casings, so as to leave the panels flush with the framing.

Architrave mouldings were usually enriched and carried up above the door, so as to form a pediment or over-door with a frieze and cornice. Early in the century over-doors were sparingly ornamented, but as time went on, decoration became more lavish, and stucco was used either in whole or in part. The illustration from 22, High Pavement, shewing an adaptation of the Greek honeysuckle pattern, is made entirely of stucco painted in imitation of wood.

In the houses of the previous century, the staircase was either circular on plan,2 or arranged in a series of short flights with heavy newels and balustrades. In the 18th century, the fashion was to ascend in two flights, with a spacious landing placed mid-way; or in one continuous flight round a circular or oval well. In either case the handrail was continuous and finished with a wreath or scroll at the foot. The balustrade was light and elegant, formed with turned mahogany balusters in alternate patterns twisted and straight, set on a cut and carved string-board.

Bromley House. Staircase and hall.

The staircase at Bromley House (1752) may be taken as a typical illustration. It commences with a fine wreath or scroll and ascends in two flights with a half landing between. The steps are four feet wide, 113/8in. tread, 53/4in. rise, 2ft. 7½in from the nosing to top of handrail, which is supported from each step by three elegantly turned balusters, two spiral and one straight. There is a fine bit of carving on the spandrel brackets at the end of each step. Several staircases, almost identical in design, and probably made in the same workshop, are still left in situ, 64, St. James’s Street (1776),3 70, St. James’s Street, Eldon Chambers Wheeler Gate, Bulwell Hall, and possibly others. In some instances (64, St. James’s Street) each step, instead of being built up with tread and riser, was cut out of the solid, a custom by no means uncommon so long as timber was plentiful.

In Willoughby House the lower portion of the staircase is similar to those before described, but the upper portion commencing from the second floor is in oak, with one boldly designed baluster on each step. Dog-gates are fixed at the top and bottom of each flight respectively, where the change in design occurs.

In some houses the staircase is conspicuous, owing to the severity of its treatment. In all such cases it was sought to obtain effect, by the use of costly materials rather than by mouldings or carving. In Lord Howe’s house, the balustrade consists of an elegant polished mahogany handrail, carried on ebony balusters tin. square, set 3in. apart.

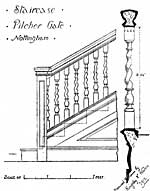

Staircase, Pilcher Gate.

There is a good staircase of a different type in an old mansion house (now used as a warehouse) at the top of Pilcher Gate, having a panelled newel in place of the wreath, and all the balusters are spirals.

A spacious hall, adorned in some cases with columns and enriched with modelled plaster-work on frieze and ceiling, was planned to receive the staircase. The last remaining examples are Lord Howe’s house and romley House; although in the latter case the full effect cannot be seen, because a portion of the hall has been screened off to form an office. In houses of any pretension, it was the custom to have a small chamber, known as the “powder box,” contiguous to the hall or landing, and communicating therewith by means of an oval-shaped window, in order that visitors might pop in their heads and have their wigs powdered up, preparatory to entering the reception room. Needless to say, these apartments have now all been relegated to other uses.

If the craftsman bestowed more care and attention on one detail than another, it surely was on the chimney-piece. When in its original setting, an old chimney-piece always has a homely look, as though it belonged to the house; but in these days when a high price is put upon genuine work of the Queen Anne and Georgian periods, it is no unusual thing to find a good old chimney-piece far away from its original position.

Plumtre House, with its “grand stucko’d front” built in the Italian Taste, and which “joined to the external beauty of the Italian the inside Conveniences of the English Taste “—stood on the north side of the Church of St. Mary until 1853-4; when the estate was sold for £8,410 and the house was pulled down to make room for a new thoroughfare from Stoney Street to St. Mary Gate (Broadway). The house was built by John Plumtre4 (1712-15) one of Nottingham’s notable Sons, a liberal patron of literature and art, a member for the Borough in three Parliaments (1706-13, 1715-27, 1734-37).

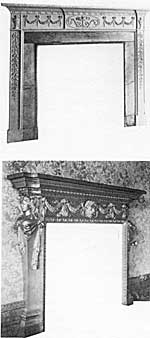

Chimney-piece, 12 High Pavement; chimney-piece, from Plumptre House (now in Bulwell Hall).

So far as I know, the only fragment5 remaining is a very fine chimney-piece, which is now fixed in Bulwell Hall. It is a fine example of wood carving in the style known as “Queen Anne,” having curious mouldings and terminal figures, of the “Caryatick Order,” as Isaac Ware calls them, “where caryatides stand at seeming ease,” at either end to support the shelf (7ft. long and 51/2ft. high). A mask surrounded by oak leaves and swags of flowers on the frieze are 18th century additions. This chimney-piece was removed to Bulwell by Mr. William Stevenson, and he it was, who caused the garlands on the frieze to be added; but apart from this information, no one could tell that it was not all original work. The marble interior and grate are modern, and the chimney-piece has recently been gilded.

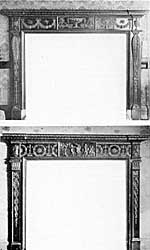

There are several fine chimney-pieces in wood and marble in a house, 26, Low Pavement6 (Mr. Gawthern’s house). In the room on the ground-floor, an alcove treated in the same style as the chimney-piece illustrates a familiar feature of the time. The graceful proportions of this room, and the refined details seem to confirm the tradition that it is the work of Robert Adam—the central tablet with figure subjects, and the leaning toward Greek rather than Roman models are very characteristic of his work. The elaborate ornamentation is carved in deal and helped out in stucco, or in some cases it is made entirely of the composition known as Adam’s stucco.

Chimney-pieces, 26 Low Pavement (Mr Gawthern's house).

This stucco was cast in box-wood moulds and used indiscriminately for external, as well as for all the finer internal decorations on chimney-pieces, doors, &c. In some cases the finer scrolls and tendrils appear to have been added after the castings were fixed. This kind of treatment, applied in a liquid form is sometimes referred to as “confectionery” stucco. Enrichment after this manner is now used only by the picture-frame maker and gilder.

(1) The original sashes in Willoughby

House have heavy glazing bars, “crown” glazing and wooden pulley-boxes

with metal wheels.

(2) Bulwell Wood Hall, and an old house in Mettam’s Yard, Hucknall Torkard,

are good examples.

(3) The figures 1776 on a spout head at rear of the building indicates

the date when this house was built. The earliest Deed extant is dated Mich.

40th Elizth. 1598, and consecutive Deeds down to 1677 refer to “2 messuages

in St. James’s Lane” which were apparently pulled down to make a site

for this spacious house.

(4) The house is not shewn in Kip’s view, but if we may judge by the style

of the architecture it must have been built very early in the 18th century.

It is shewn and illustrated in the margin of a map “published according

to Act of Parliament Nov. 30th, 1744 by Thos. Peet and Jno. Badder, by

whom Noblemen, Gentlemen, &c., may have their lands accurately surveyed

and map’d, and Artificers work measured at Reasonable very low Rates.” Probably

John Badder was the architect who designed the house, and the brother of

Thos. Peet may have been the builder, as “Peet’s Woodyard “ is carefully

shewn on the map.

(5) The Plumtre arms and a two-light Norman window built in the wall under

an archway in Broadway are in grit-stone and belong to a building much

older than the one now under consideration.

(6) Formerly known as Vault Hall. The house was sold to Alderman William

Drury (hence Drury Hill) for £103. 21 Charles I. 1645, and resold by his

grandson to William Gawthern for £500 in 1733.