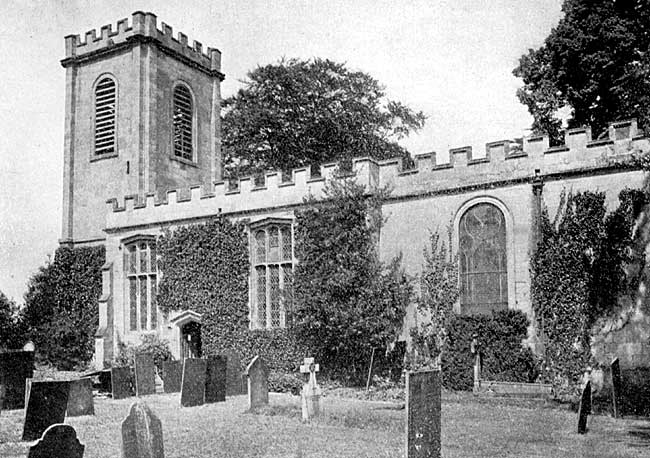

Colwick church and monuments

By Mr. George Fellows.

ON Tuesday, 14th September, 1915, the second half-day outing took place; it was on a smaller scale, for the same reason as the excursion held earlier in the season. A slight novelty, however, was introduced, as the party on this occasion availed themselves of the steamer which plies between the Trent Bridge and the river entrance to the grounds of Colwick Hall; on reaching the landing stage, the party, numbering about thirty-five, went on to the church, which, by the courtesy of the rector (the Rev. W. S. Hildesley), who was absent on duty as chaplain to the 2nd South Notts. Hussars in Norfolk, was open for the inspection of the visitors.

Colwick Church.

Our visit to Colwick brings us into touch with three notable Nottinghamshire families, viz., the de Colwycks, the Byrons, and the Musters.

The de Colwycks date back to the time of Henry II., possibly further back even than that, but it is on record that in the year 1174, a William de Colwyck paid the sheriff one mark because he sold a horse to the king’s enemies. Also in the sixth year of King Edward I., the jury found that a certain Reginald de Colwycke lived a hundred years, and that he and Philip his son had their park enclosed with hedge and ditch at their pleasure without the impeachment1 of the justices or ministers of the forest, and that the said William until now has so held it, paying his twelve barbed arrows to the king when he visited Nottingham.2 The estate consisted of two portions, viz., “Over” and “Nether” Colwick: the former comprised the church and the hall, and the latter the village of Colwick.

It is scarcely necessary to enlarge further upon the ownership of the estate prior to the time when it passed from the possession of the de Colwycks to that of the Byrons. This happened at the close of the 14th century by the marriage of Joane de Colwick, the heiress, with Sir Richard Byron, as his second wife, and so “carried this lordship to the family of Byron, a Lancashire family, whose pedigree is shown in Thoroton’s History, under the head of Newstead, as going back to the time of the Conqueror: it was thus that the Byrons first became identified with the county of Nottingham. It was not until 150 years later, viz., 28th May, 1540, that Newstead Priory was granted by letters patent by King Henry VIII. to Sir John Byron, knight, at the time of the dissolution of the religious houses.

It may incidentally be mentioned that trouble arose shortly after the marriage of Sir Richard to the heiress Joane, and a presentment was made against them (13 Richard II.) for hindering the course of the water of Trent at Over Colwick, “which is there found to be one of the great rivers of the Kingdom of England for passage of Ships and Batells (that is Boats) with Victuals and other merchandise from the Castle and Town of Nottingham to the water of Humbre and from thence into the Deep Sea. ” By the passing of an Act of Parliament promoted by the Corporation of Nottingham during the session just ended, it seems likely that this traffic may to some extent be resumed ere long.

The Monuments.

Colwick Church. Tombs on north side of chancel.

The chief interest in the church, which is dedicated to St. John, is the series of monuments in the chancel. It is unfortunate that the very inadequate light at the east end renders a scrutiny difficult. Doctor Thoroton makes no reference to these monuments in his county history, although he refers to a stained glass window, which no longer exists, of a man in “his Coat of Arms, holding his Shield, whereon also was depicted Gules, three (or four) Fusils in Fesse Argent and two Cinquefoils (or Mullets) in chief or. He was of the family of D’Aubeni in Brant Broughton: ” as the arms described are those of the Colwicks, it seems more likely that the figure in the window represented one of that family rather than one of the family of D’Aubeni of Lincolnshire.

Taking the tombs in chronological order, we find against the north wall, just outside the altar rails, the alabaster altar tomb of Sir John Byron, knight. This Sir John was a notable man, for he filled the offices of Steward of Manchester and Rochdale, and Lieutenant of Sherwood Forest, as is related on the moulded edge of his tomb; the latter office alone was one of some responsibility, for, according to a return dated 1538-9, there were in his day about 1,000 deer in the forest. According to the Muster Roll of the Thurgarton Hundred of Notts, 34 Henry VIII. (1543), we find “Nether Colwyke, Sir John Byron and xx household Servants with him to serve the King’s Grace horse and harnessed.” His name appears frequently in the state papers. It was to this knight that Henry VIII. granted the demesne of Newstead, as already stated. He married firstly, Isabel Lemington, by whom he had no issue, and secondly Elizabeth, a daughter of William Consterdine, of Lancashire, and widow of George Halgh or Haigh. In a book called The Real Lord Byron, Mr. Jeafferson tells us “he loved his wife something too soon and sought the priests blessing on their union something too late for decorum: ” however that may have been, it was thought expedient to procure a deed of gift in order to establish the son, who was born to them, in the estate. The families of Byron and Willoughby of Wollaton appear to have been on terms of close friendship, and to this several references are made in the Wollaton MSS., one or two of which may be worth recording. In the household accounts (1572) is an entry “December 25th to my Mrs that she lost at cardes at Colwyck by the hands of Mrs Elizabeth 10/-;” apparently Lady Elizabeth Byron did not scruple to play cards and win her friends’ money on Christmas Day. Let us hope she gave her winnings away in charity, for in the next year an entry shows she gave 18d. to the poor of Colwick, when she visited them with “my lady of Wollaton. ”

To this influential knight, Doctor Thoroton attributes the nickname of “Little Sir John with the great beard: ” it seems probable, however, that the historian has made an error of a generation, and that it was Sir John’s son, by the widow of George Halgh, who merited this cognomen on account of the exceptional size of his beard. This surmise is strengthened by the son’s figure on the front panel of Sir John’s tomb, where the son is represented kneeling at a faldstool and wearing a beard, which is also a conspicuous feature in his effigy on his own elaborate alabaster tomb against the south wall of the church, whilst, on the other hand, the incised representation of his father, between the two wives, on the mensa, shows no indication of his father having any beard at all.

(1) Thoroton’s History, p. 278,

gives “impediment.”

(2) Inquisitiones Post Mortem, vol. ii., p.

92.