In only one of these village churches (Basford) is there any appreciable amount of old work to be found, and even this is so intermixed with modern additions as to necessitate attention being drawn to it. In all other cases the traces of antiquity are well nigh obliterated. From the scanty information available, however, it may be assumed that shortly after the Conquest, probably in Peverel’s day, the three villages up-stream had each a small church, comprising chancel, nave, and western tower, such as would answer to Stretton’s description of Radford church as he knew it a hundred years ago (given on p. 17).

Basford and Bulwell have been visited by the Society during this year of half-day Excursions so restricted owing to exigencies caused by the war. Lenton and Radford, while not within the scope of any future itinerary, are worthy of some notice.

I desire therefore to make a record of the buildings as they stand to-day, with an account of the vicissitudes through which they have passed, before the data pass out of recollection.

NOTES AND REFERENCES to MILLS ON THE LEEN.

“See you our little mill that clacks,

So busy by the brook ?

She has ground her corn and paid her tax

Ever since Domesday Book”

Puck’s Song—Rudyard Kipling.

CASTLE MILLS. The “mills of Nottingham,” called Castle Milnes (23 Henry VI. 1444-5) are frequently referred to in State papers. Even before Henry III. had made the “new buildings” at the Castle “beautiful and gallant” there must have been more than one mill, for in the second year of his reign (1217) there is an entry of £21 18s. 6d. for repairs “to the mills under the rock of the Castle.” Their number is definitely stated in the next entry, which occurs in 1299 (Edward I.) when a charge of £6 is entered for mills “and mending three.” By the succeeding reign (Edward II.) their number had been increased to five, and the name of each mill is given. “1315. repairs to the weirs, etc., of Sparrow mill, Swallow mill, Doune mill, Dosse mill and Gloff mill.” That these were all water-driven mills and not windmills is clear from the mention of “weirs,” “watcrallys,” etc., both in this and the following extracts.

A.D. 1325. Edward II. “reparation to the houses, weirs, mills.” A.D.

1334. Edward III. “the houses in the Castle, and the walls and towers,

and the mills in the suburb require repair.”

A.D. 1362. Edward III. “repairing the chapel and a kitchen in the

Castle and four mills outside the same.”

A.D. 1366. Edward III. “for repairing and mending mills and weirs.”

A.D. 1423. Henry VI. “‘3 mylnewryghtys’ at work on 3 mills repairing ‘3

waterallys.’” &c., &c.

The mills “under the Castle rock” were on the Leen quite near to the Castle, but the “mills in the suburb” were to the west of Trent Bridge, on the north bank of the river, driven by the water of Trent conveyed across the meadow from a point near to the present Trent baths.

LENTON. Domesday: “In Lentune 4 sochmen and 4 bordars have two ploughs

and a mill.”

“Ulnod has one plough and one mill.”

There were two mills thus early in Lenton, and at least one other was established after the Priory was founded, contiguous to the site thereof.

RADFORD. Domesday: “In Redeford There [are]4 mills [rendering] 3 pounds etc.”

This was increased to four pounds in Peverel’s time; a very high valuation, as these were “demesne” mills on Peverel's own holding.

In 1224, the Vicarage of Radford “consisted of the whole alterage of that church, and four oxgangs of land belonging to the said alterage, likewise of the tythe of two mills [i.e., two of the before mentioned four mills] and of all that toft lying between the toft of the church and the waters of Lene.” (Torre. M.S.).

There are still the remains of four substantial mills in Radford.

BASFORD. Domesday: “In Baseford Pagan and Saffrid, William's men have . . . 3 mills. “Alvric held of the King. 1 acre of meadow and 2 mills.”

Only two mills remain in Basford; the upper one is still driven by water-power, but a turbine has supplanted the water-wheel.

Water wheel at Bulwell.

BULWELL. There is no early mention of mills at Bulwell, but no fewer than six were established on the Leen by the 18th century. A water-wheel is still in working within the shadow of the parish church [see sketch] and there are traces of three other mills down-stream and two up-stream, of which the highest—“Nither mill,” i.e., in relation to the more ancient and better known Forge mill—is still in work.

PAPPLEWICK. Within a mile of “Nither” mill is “Forge mill,” probably identical with the “mill of Blaccliff” before mentioned. This mill has a long history. It was erected by the Canons of Newstead, and probably used by them as an iron mill. Built into the walls of the church porch at Papplewick are two grave-covers each incised with a representation of a pair of bellows. These stones were undoubtedly used to cover the graves of officials who once had charge of the hearths in this forest smithy. It would appear that Henry II. gave this mill to the monastery at Lenton, in exchange for grants in Papplewick including another mill which the Canons of Newstede had made, “and a field of arable land upon the head of which the Canons made a Grange.” It was in use as a “hammer-mill” in the 17th century, but its early history is obscure. There were at least four mills in the parish of Papplewick and these were all converted in the 18th century into flax, or cotton mills. Forge mill is now used for grinding corn. Middle Mill has gone; the position is indicated by a gaunt three-story stone house which stands by the footpath from Bestwood to Hucknall. The old “Waukmill” for fulling cloth (now corrupted to Warkmill) near Papplewick Grange, is said to have been turned by a “breast-wheel” of enormous size. The mill has altogether disappeared from view; there is, in the vicinity, a cluster of stonebuilt dwellings with tiled roofs which were used by the workers in the cotton mills.

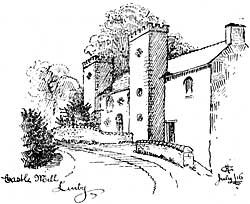

Castle Mill, Linby.

LINBY. Domesday: “in Lindeby there was a priest and a mill, etc., etc.

A Perambulation of the Forest boundary in 1232 reads thus:—

“thence by the middle of the town of Lindeby, to the mill of the same town which is on the waters of Lena.” A new mill was erected on this site near Papplewick Lake which came to be known as Upper mill or Castle mill. It is in a pseudo-gothic style of architecture with embattled towers built of local stone and “pebble-dashed.” The old mill stream and wheel is still in use for grinding meal for cattle, etc.

In 1785, James Watt here set up the first engine built by him for a cotton mill. The cotton industry was then in a flourishing state in this district, and numbers of poor boys of nine or ten years of age who were “on the parish” were brought from London workhouses and apprenticed in these large flax mills. The parish registers of Linby contain repeated entries of the death of “a London boy.” Their bodies, 163 in all, lie buried in the north-east corner of the churchyard, a pathetic result of the churchwarden and overseer poor-law days which came to an end in 1834.

It was to this mill that the damage was done when Lord Byron, after having held up the water of the reservoir, suddenly let it go until the whole valley was flooded. A lawsuit ensued, but the only compensation that could be obtained was a beautiful marble chimney-piece which is said to have been brought by Lord Byron from Italy. This was originally fixed in the drawing-room at Papplewick Grange, but has now been removed by the owner to his house at Cold Overton, near Oakham.