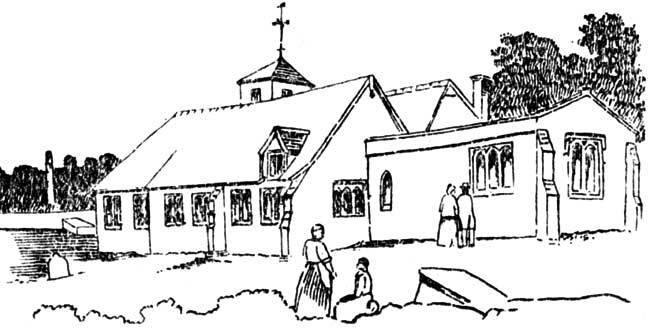

HOLY TRINITY, LENTON.

Church at Old Lenton, Notts. 1843. Now pulled down. From an old painting by J Smyth.

In spite of modern developments, a general air of antiquity still lingers in the vicinity of the great Cluniac monastery of the Holy Trinity, founded at Lenton by William Peverel in the dawn of the 12th century (c.1105).

Of the once majestic buildings, nothing remains save a broken length of rubble walling, two column bases in situ, and scattered fragments of worked stone in gardens, in the banks of the Leen, and in the walls of the chapel-of-ease now occupying the monastery site. This chapel is rendered very interesting, from an archaeological point of view, on account of these old stones, and also because it stands in a direct line with the long history of the Priory, which has been ably recorded by the late J. T. Godfrey.

In mediaeval times the parish church must have been contained within the monastery, for although the benefice is mentioned in the Taxation Roll of 1292, and the Inventory of church goods, taken in the reign of Edward VI., is still extant, together with the parish registers from 1540 onwards, no trace of a separate parish church has been found anterior to the Suppression.

It seems highly probable, therefore, that the nave of the monastic church was devoted to the needs of the parish. In the will of Sir Robert Burton, pbr., Vicar of Lenton, proved May 7th, 1516, he “desires that his body should be buried in the parish church of Lenton, on the south side of the high altar.”

With the suppression of the monastery in 1537, followed by the execution of the prior and some of his monks on a charge of treason in the following year, and the consequent desecration of the monastic buildings, came the necessity to provide a new parish church. There had long been a tradition that this was built upon the site of the chapel of the Hospital of St. Anthony, which stood within the precints of the monastery. This tradition was more than confirmed during subsequent building operations in 1884, for it was then discovered that the walls of the present chancel are actually the walls of the ancient chapel. A piscina niche in situ was disclosed, and the discarded foundations of the nave of the chapel were uncovered. It seems clear, therefore, that a parish church was evolved by building a new and wider nave to the old chancel of St. Anthony’s chapel. The level of the chancel floor was raised, new windows were inserted in the old walls, and a new roof was put on. All the new work was done in the Tudor style of architecture which at that time prevailed.

This building served the needs of the parish until 1842. As the parish was then developing very rapidly, a new site between Old and New Lenton was secured, and a new church, designed by Mr. Stevens, of Derby, was erected thereon. The building when completed was consecrated (Oct. 6th, 1842) and dedicated in honour of the Holy Trinity.

The old church on the priory site went out of use, and the nave was eventually demolished. The chancel and vestry were left standing and “put into good repair and condition in order that Burial Services may be performed therein.”

In July of that same year (1843), the foundation stone was laid of a chapel-of-ease in a distant part of the parish (St. Paul’s, Hyson Green). To this church, when completed and consecrated (April 18th. 1844), were removed the old reading desk, the pulpit, and the church bell originally dated 1591, was broken and replaced in 1829.

Thus matters stood until 1883. On the 22nd November in that year building operations were resumed. The old chancel was again refitted, new windows were inserted in the old walls, a new nave and aisles were built, and the old church, which is still known as the Priory church, was brought into regular use again as a chapel-of-ease. The mother church has thus become a daughter church, while still occupying the monastic site.

In spite of these vicissitudes “some slight traces of old work remain,” to quote from the guide books, and these traces are eloquent of the story of the past.

1. The chancel walling is in part the remains of the chapel of St. Anthony, and some of the stones re-used in the south aisle are ancient stones, as witness the scratch dial on the front face of the south eastern buttress.

|

2. The riser to the altar step is formed with two slabs of stone, about 6in. thick, carved on one edge, and together measuring 91/2ft. long. These stones, together with a coped coffin lid, were discovered about 4ft. below the post-Reformation chancel floor; a level approximating with the original floor of St. Anthony. The ornamentation is so much akin to the decoration on the old font, now in New Lenton Church, that I have no hesitation in pronouncing them to be contemporary.

3. The font has been frequently illustrated and described. It is only necessary to mention here that it is Norman in style and unique in design. After serving for upwards of 700 years in the monastic church, and then in the first separate parish church which stood upon the site, it was cast out, and occupied a place in the garden of a modern house built upon the site of the Priory gatehouse. It was eventually re-installed in the new church of Holy Trinity at New Lenton, where it still continues.

Seeing that Lenton Priory was famed for its guest-chambers, which were occupied from time to time by a long line of Royal1 and notable visitors, it is not presumptuous to think that some of the greatest in the land may have received baptism at this font.

One such baptism at any rate is definitely recorded. A Nottingham Jury in 1284 found that “William son of Nicholas de Cauntlow was born in the abbey of Lenton and was baptized in the church of the abbey on Palm Sunday 21 years before” (Calendarium Genealogicum 1. 139). To do ample justice to this brief statement would require the pen and the imagination of a weaver of romance; for although its purpose was simply a certificate that the said William had reached his manhood, many other things may be learned therefrom.

Sufficent to say here, that Nicholas Cantelupe, the father of William, had inherited the manors of Greasley and Ilkeston by his marriage with Eustachia, sister and heir of Hugh Fitz-Ralph. Being a doughty champion in the cause of the Baronage against the King, he was away in the south on matters appertaining to the welfare of the Kingdom when the auspicious event occurred; and seeing that his new house at Greasley though being built was not yet completed, the guest-chambers at Lenton became a place of sanctuary in his absence,

The son thus born in the odour of sanctity was present at the Coronation of Edward II. (1307) and died in the following year. His eldest son William succeeded, but died before he was summoned to Parliament as a baron, and thus the inheritance came to his younger brother Nicholas, the friend and companion of Edward III., who, having obtained a “license to crenellate” in 1341, proceeded to fortify the house at Greasley which his grandfather had built, and founded in 1343 the Charterhouse at Beauvale.

|

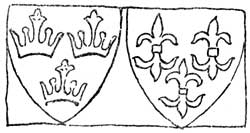

4. Built into the external wall above the west door is an old stone containing two carved shields of arms. Many attempts at elucidation have been made, but so far without success. I am disposed to think that the armorial bearings are not personal, but rather such arms as were attributed to an ecclesiastical foundation, or to a mediaeval saint. It is permissible therefore to conjecture that the stone was part of a monument or shrine; or, seeing that both the emblems apply to saints who were credited with miraculous powers of healing, they probably formed part of the decoration of the chapel of the Hospital of St. Anthony; an institution founded in olden time “for such as are troubled with St Anthony’s fire (erysipelas). I take the three crowns on the dexter shield to be the emblem of Saint Ethelred, king and martyr, and the three double fleur-de-lys, on the sinister shield, to be the emblem of St. Thomas of Hereford.

Ethelbert, King of East Anglia, was betrayed and foully murdered by Offa, King of Mercia, A.D. 782. His body was subsequeutly removed and buried in the Saxon cathedral at Hereford, where miracles are said to have been performed beside his grave. Offa was so much impressed that he caused a stone church to be erected in place of the wooden one, and this, in due course, became the cathedral church at Hereford, the ancient dedication whereof to S.S. Mary and Ethelbert still survives.

Thomas Cantilupe, a later Bishop of Hereford, was the last Englishman to be canonized, prior to the Reformation. He died August 23rd, 1282, at Civita Vecchia, while on his way to interview the Pope on matters concerning his diocese. His flesh was buried at Santo Severo at Orvietta. His heart was brought to the monastery of Ashridge,2 Bucks., and placed in a repository “made with exquisite art” which the founder had prepared for it “in a guilded shrine which contained a relic of Christ's blood” on the north side of the church. His bones were brought to Hereford, and the chronicler tells us that Gilbert, Earl of Gloucester, one of the bishop’s strongest opponents, touched the casket containing the bones “whereupon they bled afresh.” Then commenced a long series of miraculous cures, no fewer than 425 persons being cured of ills of body or mind. In 1320 a Bull of Canonization was obtained, and as the shrine of St. Ethelbert had by this time become “stale and unprofitable,” pilgrims flocked to the shrine of the new Saint Thomas. The arms of the See were changed from Gules three crowns. Or with a roundel between Ethelbert, K. & M. to Gules three leopard heads reversed, jessant-de-lys,3 the arms of Thomas Cantilupe. The saint was a son of William Lord Cantelupe, and cousin to the William Cantilupe who was born in the priory at Lenton, as before recorded.

|

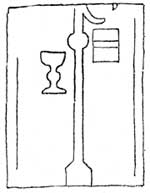

5. In an upright position, to the south of the west door, is a fragment of an incised grave cover. As the symbol on the dexter side of the cross-shaft is a chalice, and on the sinister side an open book, this is doubtless the memorial of a former vicar of the church. The work is of 14th century character, and similar in detail to other stones in the district.

It is known that two priests died during the first half of the 14th century while holding in succession the office of vicar of this church. Another vicar died in 1442, and willed his body to be buried in Lenton Church, near the grave of Robert de Thornton, who was vicar early in the 15th century. In the absence of any name or date, it is not possible to determine which of these was commemorated by the relic.

6. There is a tradition that, after the Suppression, the porch of the monastic church was removed to the south aisle of St. Mary’s, at Nottingham. After long experience, I have found that in matters archaeological at any rate it does not always follow that “legends are embellished facts,” or that “every legend had its origin in some authentic happening.” I have made a very careful examination of this porch, but beyond the fact that it obviously does not fit in well with its present position, I can find nothing to support the tradition that it originally came from Lenton. The connection between the Priory and St. Mary’s was long and intimate, the prior and convent being patrons of the vicarage until the Suppression and this probably first gave rise to the story.

While visiting the priory site, so redolent of the name and fame of Peverel, the visitor would do well to step across the way and take a look at a small brick building at the rear of the White Hart Inn. It is a plain whitewashed structure, having barred windows and studded doors, which give indication of its former use, for here in this “the Peverel prison,” debtors were wont to be confined until their indebtedness was discharged. The building was in use for the purpose until 1842.

(1) Henry III. 1230. Edward I. April 1302 and again April 1303. Edward II. In year of Accession, and again 1323. Edward III. 1336 and on other subsequent occasions. (2) The monastery of Ashridge was founded by Edmund of Cornwall, the brother of Henry III. (A.D. 1257) “to a new order of men, never before known in England, called Boni Homines, the Bonshommes.” Abbot Gasquet). (3) The arms of William Cantelupe are shewn with globular boss instead of the leopard heads.—Temp. Ed. I. Col. Arms.