MANOR-HOUSES.

Of the old manor-houses, Algarthorpe is now only a name. It stood on the left bank of the Leen about half a mile southward of the church. Since it became the chief residence of the Eland family in the reign of Edward III., it was more generally known as Eland hall.

Basford hall, on the western border of the parish is now a modern structure.

Basford House (A Nicholson, 2005).

Basford house, the comfortable, square, brick-built house near the church, which still wears a distinguished look, is the Georgian successor of Bassa's manor-house. “Its panelled rooms and its old world garden (which formerly extended to the church and the Leen) with its pools of gold-fish, and its little tree grown from a cutting out of the willow on Napoleon's tomb,” as described by Miss P. C. Carey, have now lost all their attraction. Only one of the old trees, a splendid beech, remains; and a cedar tree, planted on the poet's twenty-first birthday. The entrance-gate is a charming example of local wrought iron-work, and a spout-head bears initials and date L. T. C., 1739. Thomas Bailey, author of “Annals of Nottingham,” lived here at one time, and it was here that his distinguished son, Philip James Bailey, wrote “Festus.” The poem, which took three years to write, was published in 1839, and the greater part of it was written in the old garden; since then the Midland Railway Company, who now own the property, have encroached upon it and taken away much of its beauty. A Grecian column, surmounted by a vase, which formerly stood in the garden, having been erected by Thomas Bailey to commemorate the passing of the Reform Bill in 1832, is now utilised as a monument to the Spencer family in the cemetery on the opposite side of the way, and near by it is the grave of the historian.

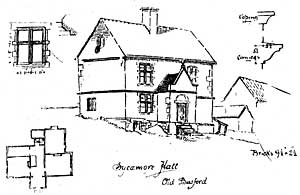

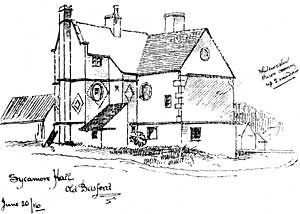

Sycamore Hall, Old Basford.

Sycamore Hall. This building, although of no great antiquity, is fast falling to decay. Denuded of its pleasant gardens and sheltering sycamore trees, it is but a shadow of its former state.

The walls are built with bricks, stone being sparingly used for angle quoins, cornices and dressings. The lower windows have mullions and transoms in the ordinary way, but some of the upper windows are contained within oval frames of stone-work. A coat of arms once filled the tympanum over the entrance doorway but it is now all cut away and destroyed. This is to be deplored, as it would undoubtedly give a clue to origin and ownership. It is said that a new Eland Hall was erected in Basford, in Colonel Hutchinson’s time, to the north of the church. I can only suggest that this is the building referred to. The brickwork and the stone quoins and cornices correspond with the re-constructed church of St. Nicholas, at Nottingham, commenced in 1671, and thus give an approximate date, but so far I have met with no other confirmation.

Internally, nothing of interest is left save perhaps a newel staircase which ascends in a continuous flight from ground-floor to attics.

The name “Sycamore Hall” is of comparatively recent origin, and I do not look upon this house as one of the ancient manor-houses. Three other houses in the vicinity lay claim to the distinction. One of these stands just above the mill in Mill Street; another, now converted into a pair of dwelling-houses, is a little further to the southward in Bagnall Road, but to my mind the most likely site is near the junction of Bulwell Lane and Southwark Street. Here, an old house overshadowed by yew trees, formerly stood on the north bank of the Leen, just where the old road recrossed it by a ford, in much the same relative position as the manor-house about half a mile lower down stream, which may have given rise to the lower ford being known as “le bas ford,” hence Basford.

ST. MARY’S, BULWELL.

The old church, Bulwell.

Bulwell at the present time is the antipodes of Bulwell of former days. Gone is the verdure from the valley. Gone are the trout from the stream. Gone are the rustic bridges and trackways. All gone before the march of progress and manufacture. The ancient village church is gone, and even the early dedication thereof is lost in obscurity: for although the new church is known as St. Mary's, as the old one was for some centuries before it, there are reasons for thinking this was not the original dedication. It is a general rule that the village feast synchronizes with the patronal festival, and as Bulwell Feast has long been celebrated on the 5th November, or on the first Sunday after that date, it seems unlikely that St. Mary the Virgin was the original patron saint. The York Records are silent on the matter, and we can only surmise that one of two things has happened. Either a personal dedication was originally adopted, as in the neighbouring parish of Nuthall, and this was exchanged for a biblical saint in after years; or it was one of the common instances of a compound dedication from which one of the names has been dropped since the fame of its owner began to pale. Anyway, the date of the Feast is the day ascribed to St. Elizabeth, cousin of the Virgin, and mother of St. John Baptist, a saint in whose honour no ancient dedication now survives.

The old church was demolished in 1850. It occupied a commanding position on the edge of the forest waste, on the left bank of the Leen. Its exact position and extent may still be determined by the monuments which abutted against it, and the memorials of Rectors in the chancel floor which still remain in situ. No description of the old church, other than a picture painted by a former Incumbent,1 is extant, and documentary references are but meagre. It is not mentioned in the Domesday Survey, but not long thereafter “Philip Marc, the Sherif, said he held Bulwell and the advowson of the church by demise from King John.” (Thoroton). From this, and other similar references, it is clear that a church was in existence here, as far back as the 12th century at any rate. In 1776—a bad time for church restoration—side aisles were added to the ancient fabric, which would appear to have then been in a tottering condition, for in 1800 the tiled roof was taken off and a slated roof substituted, and the tower walls repaired. Half a century later the old church was entirely demolished, and replaced by the present edifice which stands a little to the south of the old site. Two bells which hung in the old steeple are all that escaped destruction. They were left in the churchyard for a time and eventually recast by Taylor of Loughborough. They are now included in a ring of six bells which was installed in the new tower in 1860, so that nothing belonging to the old church now remains save the Registers (1621) and a number of gravestones. There were three bells in the old tower, and there is a tradition that one of them was taken to Basford church, but I can find no evidence whatever in support of this. (See Basford).

The list of Rectors is fairly complete, commencing with the name of William de Honeshill, presented to the living by the King, 8th April, 1283.

Bulwell parish church in 2005.

The graveyard is an extensive one and contains many memorials having quaint and interesting inscriptions. One of the earliest I have noticed is a slate floor-stone to Thomas Smith of Papplewick, “lately of Bulwell Forge,” who died December 27th, 1659, and his father, Ralph, who died ten years later. Parallel with it, but much earlier in date, is a large slab of local stone, 7ft. 7in. long, 3ft. 1in. wide, upon which may yet be traced portions of an incised cross, with an open book on one side of the shaft and a chalice on the other, (indicating the grave of a priest or rector), and an effaced black-letter inscription on a scroll at the top. Three other rectors are commemorated by slate stones to the eastward of these, viz.: Rev. Thomas Greening, 1666; Abraham Turner, 1729; Thomas Beaumont, 1771. These stones, now extramural, originally lay in the floor of the old chancel.

As at Linby, there is a plot of ground at the western extremity of the churchyard, crowded with nameless graves of “poor children from London”—another pathetic reminder of the time when children were sent out from London workhouses to work in the cotton mills of the Leen Valley.

(1) Rev. Charles Allen Alfred Padley, of Bulwell Hall, patron of the Living and Perpetual Curate, died May 11th, 1856.