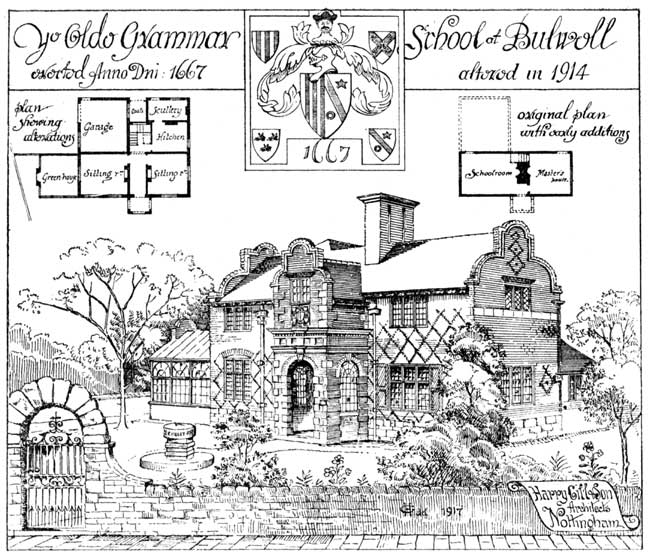

YE OLDE GRAMMAR SCHOOL, BULWELL.

In the centre of Nottingham's busy suburb of Bulwell, in touch with a ceaseless flow of traffic, there stands, within a walled garden, a building which savours of a former generation. It has “shaped” gables after the Dutch manner, the brick walls are diapered with dark coloured headers, the roofs are covered with irregular hand-made tiles, and the whole aspect of the building is redolent of “Restoration” days.

From a deed still extant we may learn that the building was erected in 1667, by George Strelley, of Hempshill, as a Free School “for the educating and teaching young children of the Inhabitants of the Parish” (Bulwell).

This building is now being restored and converted into a dwelling-house, and great credit is due to the owner, Mr. P. G. Chambers, for the conservative spirit he has displayed. It was illustrated and described in a general way in the Transactions of the Society for 1907, but further details are now available.

When the walls had been stripped of the thick growth of ivy preparatory to repairs, it was plainly to be seen that the work as it now stands had been built in instalments. The first portion was built during the lifetime of the founder, and comprised a schoolroom and master's house, in a plain oblong building of two storeys in height, having a shaped gable at either end.

As the windows were in the ends and at the back, the front wall was ornamented from end to end with continuous diamond-patterns, save for the space occupied by the entrance door. The porch is obviously a later addition, for although it is built with like materials, it is not bonded to the main building throughout any portion of its height. Moreover, the diamond - patterns in the south wall, formed with the “vizzylings” or dark ended bricks which came into contact with the flame in the “clamp” wherein they were burned, are continued behind the porch and stop against the doorway in a proper manner, thus proving that the porch was not contemplated when the front wall was built. It appears to have been added a few years later after the death of the founder in 1673. A panel over the entrance contains an achievement of arms.

The heraldry had become weatherworn and partly effaced, but with diligent care, and the generous assistance of Mr. J. C. Warren, it has happily been rescued from oblivion. By the generosity of Major G. C. Robertson, together with a contribution from the funds of the Society, the panel has now been restored. The sculpture was undertaken by a student of the Nottingham School of Art, and the blazon by one of our own members: Mr. Alexander Gascoyne. The panel comprises a central shield bearing Paley of six. Argent and azure, for Strelley impaling Argent, a bend azure between a mullet in chief and an annulet in base, gules for St. Amand.1 Surmounted with mantling and crest. An old man’s head couped and full faced, on his head a cap gold turned up with sable.

Four smaller shields, one in each corner, are blazoned as follows:—

(1) Paley of six, argent and azure—Strelley (Grandfather).

(2) Argent, on a Saltire azure five water bougets or — Sacheverel (Grandmother).

(3) Argent, three boar’s heads erased sable—Reding (Mother).

(4) Argent, a bend azure between a mullet in chief and an annulet in base gules—St. Amand (Wife).

George Strelley was the last but one of a long and illustrious line of Strelleys of Strelley, grandson of John Strelley, of Hempshill, and Anna, daughter and heiress of Patrick Sacheverell, of Hempshill. He married Ann, daughter of John St. Amand, of Mansfield. He was Mayor of Plymouth in the year 1667. Died February 10th, 1673, aged 63. A fine wall tablet to his memory is in the south transept of St. Andrew's, Plymouth.2

At a subsequent date the schoolroom was extended northward, which necessitated the windows being brought from the back wall to the front, where they were inserted without any regard to the symmetry of the diamond-patterns before mentioned. In connection with the diapering it is interesting to notice that the patterns in the gables are not truly centred. The builder apparently had an aversion to cutting his bricks, and preferred to work with full “headers” or “stretchers” even though it led him 41/2in. out of the central line.

Beneath the cill of the chamber window in the gable, a course of bricks set on edge excited my curiosity. Upon examination I found, embedded in each end wall, a tie beam of oak about 7in. by 5in. scantling, but now too much decayed to yield accurate dimensions. The tie was slotted on to a long and strong oak dowell upstanding at each end of the plate, the course on edge being built in front of it to hide it from view. The jambs and muntins of the chamber window are mortised and tenoned into the tie, which thus serves also as the window cill. Although more than half a century had elapsed since “timber framed” houses gave place to houses built entirely with bricks, the builders apparently looked upon the new style with a certain amount of distrust, and were not yet able to shake themselves free from the constructional methods of a former generation. But their idea of adding strength proved to be a source of weakness, for the oak tie, being hermetically sealed in the wall, has mouldered into dust.

Here, then, we have an interesting example of the methods and building materials in use 250 years ago.

When brick building first came into vogue in this district, early in the 17th century, and indeed for some time thereafter, it was customary to build upon a stone foundation. In the building under notice all the walls (with the exception of the porch) stand upon a base of local hammer-dressed stone which serves as a plinth to the brickwork above.

The Old Grammar School, Bulwell (A Nicholson, 2003).

The district is still famous for the two excellent kinds of walling material that were then employed. It abounds in good beds of calcareous limestone, overlaid with a covering of clay. The stone is used for walling and for pavings, and it also yields, when burnt, a good lime for mortar or plaster. The clay is extensively worked for bricks and terra cotta, and is also used in the manufacture of flowerpots.

In all probability the bricks under notice were manufactured on the site, the clay being dug out of the ground and baked in a clamp. The bricks average in size 91/4in. by 21/4in. by 41/2in., and thirteen courses rise 3ft. All projecting courses are protected with a creasing formed with three courses of roofing tiles.

The roofing tiles are also made of local clay. They are 111/2in. long by 7in. wide, dark and weather stained on the exposed surfaces, but clean and bright-red upon fracture. They are hung with one nib to riven oak laths and bedded in mortar. Generally speaking the tiles are as sound as when they were first put on, and it is rather curious to find that where any decay is found it is, in all cases, at the “head,” where the tile is most protected from the weather, and never at the “tail” where it is exposed.

The main roof has spars of fir timber 31/2in. by 31/2in., mixed with oak spars 4in. by 3in., 15in. centres, supported by oak purlins 6in. by 6in. The porch roof has couple spars of oak, halved and trenailed at the ridge without any intervening ridge piece. It seems probable therefore that the main roof has been subsequently renewed and raised. Further confirmation of this is found in a chase in the brickwork at the back of the gables, about 9in. below the present line of rake. This was evidently intended to receive the tiles and “collaring” of the original roof.

The floors are constructed with 41/2in. by 3in. joists, splayed at the ends and notched into 11 in. by 9in. beams, all in fir timber and still clean and bright. The timbers are seen overhead, unceiled; the plaster floors, which are about 3in. in thickness, are laid on riven oak laths and skimmed with plaster on the underside. Floors made with Bulwell lime plaster were in vogue in this district until quite recent times. After the floor was laid it was usual to pound the surface with a large boulder from time to time, in order to delay the setting of the plaster as long as possible. By this means a durable, homogeneous floor was obtained having avery smooth and even surface. The floors in question, notwithstanding over two centuries of wear, have still a metallic ring, nor do they show any signs of disintegration.

A steep, straight flight of stairs, executed in chestnut, gave access from the masters’ room to the chambers above. The treads in most cases have been renewed in deal during recent years, but the chestnut risers are still in fairly good condition.

The Old Grammar School, Bulwell (A Nicholson, 2003).

The doors are small in size, being in some cases less than 6ft. high, framed in two panels, and hung to solid frames, all executed in oak. An attempt was made to exclude all draughts by rebating the edges of the outer doors as well as the frames. This, of course, necessitated the use of strap hinges with projecting knuckles, all in wrought-iron.

Only two of the original window-frames remain ; they are framed solid in oak, pinned together with trenails, chamfered on the inner side, and without any opening casement. The later windows are all in fir [which gradually became general for joiners' work from this time onward] moulded on the inner side, fitted with opening casements hung on wrought-iron hinges, and glazed with square “quarries” in lead cames. With one exception all the old leaded glazing had been replaced with sheet glass, but there are indications in the frames to show where the original iron stancheons and saddle bars were fixed.

In carrying out the repairs, great care has been taken to preserve the old work wherever it was possible to do so; where alteration or rebuilding was imperative, old material has been used as far as possible. There were no rainwater spouts on the old building. New eaves spouts of wood, lined with lead have been fixed, the fronts whereof are enriched with lead “pateras,” cast from models supplied by students of the Nottingham School of Art. The rainwater heads are either old ones obtained in the district, or new ones made to correspond therewith. A sun-dial has been set up in the garden ; the base is an old millstone from one of the Leen-valley mills ; the shaft is built up with old bricks ; the head is cast in lead in conformity with old work, and the brass dial has served its day and generation in the grounds of an old hall in the immediate vicinity. The garden is entered through an arched gateway; the wrought-iron entrance gate is new, but made up from patterns of 17th century work in the district.

(1) The family appears to have

migrated from St Amand, a village in France, on the “Hindenburg line,” and to have settled in

Nottingham in the 14th century The same arms were borne by the Samons

of Nottingham, “benefactors of St. Mary's Church, and by the Salmonds

of Annesley Woodhouse, benefactors of Selston Church, to whom a grant

of land was made by the Prior of Beauvale, 10 August, 5 Henry VII.

(2) The tablet bears a quartered shield (1)

Paley of six, argent and azure—strelley (2) Argent, an eagle displayed sable armed anil langed

gules—somerville (3) Argent, on a saltire [sable] three water bougets

of the first—sacheverell (4) Argent, a chevron between three martlets sable—

5) Or, a fesse dancette sable—vavasour (6) Argent, three boar's heads erased sable—reding. (7) Quarterly

one and four Argent, a bend azure between a mullet in chief and an annulet

in base gules , two and three Argent, a bend engrailed sable—st. amand.

(8) Paley of six, Argent and azure—STRELLEY.

On either side Strelley impaling St. Amand, and at the bottom Strelley

alone. Erected by Mrs. Ann Strelley, widow, daughter of John St. Amand,

of Mansfield, in memory of George Strelley, her late husband, lineally

descended from Strelleys of Strelley, and “Mayor of this Borough in

the year 1667.” He died February 10th, 1673, aged 63, leaving issue

only George “his sonne and heir.”