It was almost a century later, in the thirteenth year of the reign of King Edward I. (A.D. 1285), that the following proclamation was issued:—"And the King commandeth & forbiddeth from henceforth neither fairs nor markets be kept in churchyards for the honour of the church." (Stat. II. Chap. VI.)

Again, after another century had run its course, our own Archbishop Thomas Thoresby, issued a general mandate (18th April 1354), followed the next year by a prohibition special to Worksop:—"Let no one in church, or porch, or cemetery, on Sundays & holy days, keep market or place of selling; let wrestlings, archery meetings, and games be forbidden therein. (1367 Wilkins iii. 68) Strange to say, in a later statute [12 Richard II. C. VI.] servants were again ordered to amuse themselves with bows & arrows on Sundays, but to give up football and other games."

And thus, after yet another century had run its course, there came another prohibition, for in "Dives et Pauper" 1493 (2 Comm. C. XVI.) we find, "no markette sholde be holden by vytalers or other chapmen on Sondaye in the churche, or in the churche yerde, or at the churche gate, ne in sentuary ne out."

The references to archery in the foregoing extracts will account for the arrow-sharpening marks which abound on the south wall of many ancient churches.

I know that there is much diversity of opinion concerning the origin of these marks. I have found them in many villages on the outside of the south wall of the church; in one instance (Wilford), I have found them inside the church; on the chancel walls and on the east face of the pier-arcades, where they were probably made at a time when the chancel lay derelict, previous to rebuilding. At Barton-in-Fabis, they may be seen amid a multitude of initials and other devices, both inside and outside the south porch. This fact is sometimes quoted in support of a negative argument, as this porch was not built until near the end of the 17th century,—see keystone. But it must be borne in mind that in spite of 1693. previous prohibitions, the Laudian clergy supported the issue of a "Book of Sports" by King James I. in 1663, wherein all parishioners were urged to practise athletic games in churchyards on Sunday afternoons. As the walls of the south aisle at Barton are built with river-borne gritstone, the fine grained local "water-stone" of the porch was naturally resorted to. I have also found them on quoin-stones away from the churchyard; but only in villages, where the buildings so used stood in an open space, more suitable for archery practice than the churchyard (Barnby-in-the-Willows). In all cases, they are deep, narrow, vertical grooves, set in rows and quite distinct from the broad-shaped depressions to be found on jambs of porches, on rims of fonts, and on parapets of bridges; in fact, wherever soft fine-grained stone was used. These latter marks are obviously due to sharpening of blades, but some of them are quite recent in date.

The secular affairs of life, no less than its religious obligations brought the people to the church door. It was in the church porch, or the chamber above it, or in a screened enclosure at the west end of the church, that village children acquired the rudiments of learning, taught by the parish priest, or by a chantry priest, if there was one who possessed sufficient education himself to be a "scolemaister":—not always the case by any means. Many chantry endowments made provision for "a prieste to helpe the Vicar, and to teache children." Hence Shakespeare's allusion to "a pedant that keeps a school in the church" (Twelfth Night. Act III. Scene 2.)

The church porch thus became the forerunner of the village schoolhouse. John Evelyn records in his Diary, under date 1624 "I was not initiated into any rudiments until near four years of age, & then one Frier taught us at the church-porch of Wotton" (Surrey). This porch has since been modernized, but at that time it had a tiny chamber above it, which was used as a school.

Not only the pedant, but the pedlar also, made use of the church porch. From time immemorial, as previous quotations have shewn, goods were exposed for sale in the churchyard, and sometimes the wares of the pedlar were actually spread out enticingly on the stone benches of the porch, the better to attract the fancy of the devout, on leaving after the service. For instance, complaint was made by the churchwardens of Riccal that "Pedlars come into church porch at Feast time & there sell their merchandise" (York Fabric Rolls A.D. 1519). The church likewise became a repository for goods of another sort; for until poor-laws were enacted in the reign of Queen Elizabeth (1601), the poor and needy of the parish were dependent, for even the necessaries of life, upon doles.1 It was not at all unusual, therefore, for the benevolent to make provision for loaves of bread, &c., to be distributed on Sundays after morning service; and this custom lingers even yet in remote villages. That it was once very general, may be gathered from notice boards.

For instance—in the porch at Beeston, there is a painted panel containing:—

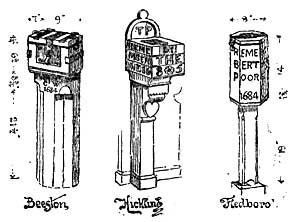

The admonitions to "Remember the Poor" were familiar to all who entered the church; for near to the door stood a pillared alms-box of stout oak, made secure with iron bands and padlocks. Post Reformation alms-boxes may still be found at Beeston, Eakring, Edwalton, Car Colston, Fledboro', Hickling, Hockerton, Kelham, Kirton, Rampton, Sutton-cum-Lound, South Muskham. They are all very similar in design, and bear the initials of the churchwardens, date, and a bold request to "Remember ye. Poore," while the pre-Reformation alms-boxes, which alas! have all disappeared, were often ornate in design, and bore a variety of texts chiefly taken from Tobit's instruction to his son Tobias with respect to almsgiving. (Tobit. Chap. IV. v. 7—11.)

In these modern days, the, bulky parish notices attached to church doors all over the land are but the survival of a custom established even long before the Norman Conquest. In those far off days, did a beast stray from its owner's crewyard, or a sheep from the fold, notice thereof had to be displayed at the church door; if an outlaw was proclaimed by the sheriff, if a leper was banned as unclean, if an accusation was brought against a tenant or a bondsman, or if a thief or a murderer abjured the realm and was banished, notification thereof was made at the church door. If a war levy was to be raised, or a church-rate collected, full particulars were posted at the church door. It was here also, that all kinds of legal business were transacted. "In an informal fashion, the clergy of the church filled the place of the village notary; for the fly-leaves of the books used at the altar were utilized for various kinds of memoranda, and an entry, made by the priest in 'Christ's Book,' or in a 'Gospel Book,' could be appealed to as a legal record of a transaction." (Baldwin Brown's Arts in Early England.) In many villages, legal documents were taken to the church for safe keeping and stowed away in the stout iron-bound oak chest generally to be found either in the church or in the porch chamber.

Criminal, as well as civil cases were dealt with in the church; for from very early times, every church and every churchyard had the privilege of sanctuary; and thus, the fugitive, who fled from the consequences of his crime, fell into the hands of that ancient officer, the Coroner, whose manifold duties were discharged under the shadow of the church. For centuries, the Coroner's inquest was wont to be held in the church porch. Dr. Cox has traced the custom in Derbyshire, back to the 13th century. He tells us that the enquiry was usually held on a Sunday, twenty-four jurors, i.e. "12 sworn men" and twelve jurors called from the four nearest townships, being in attendance to ascertain the cause of death. The corpse was viewed in the church porch, and the subsequent enquiry was conducted, either in the porch or within the church. ("Charles Adderley the Crowner sat upon him in Twyford Church. June 24 1669.") There is also a well-known case at Pleasley, on the border of Notts, and Derbyshire, where the following entry was found written on the loose leaf of an early register—" 1573. Tho Maule fd. hunge on a tree by ye wayeside after a druncken fitte April 5. Same nighte at midd nighte buried at ye. nighest crosse roads wt. a stake yn. him, manie peopple from Manesfeilde." (Parish Registers of England, p.114.)

The banishment of the murderer and the felon also came under the jurisdiction of the Coroner. The right of sanctuary within the church lasted for a period not exceeding forty days, during which time the parishioners were to provide the fugitive with food, and the four nearest townships were held responsible for his safe-keeping. Then, unless his offence had been "purged" by the interposition of his friends, or by the priest of the church, he must either give himself up to justice, or confess his crime and "abjure the realm." In the latter case, in the presence of the Coroner, with twelve representatives from the four townships in attendance, the culprit was stripped of his clothes, and clad in a single garment of sackcloth, was taken to the churchyard gate or stile, where a cross of white wood was given into his hands, and a seaport assigned to him, with instructions as to route and distance to be travelled each day, keeping strictly to the highway all the time. He then took the oath something after this wise:—" I . . . . for the crime of . . . . . which I have committed, will quit this realm of England, never more to return, except by leave of the Kings of England or their heirs, so help me God & his Saints."

According to a number of Coroners' rolls still extant, such a scene at the churchyard gate must have been at one time very familiar.

Beverley and Durham were the most noted places of sanctuary in the north; for there, not only in the church, but also within a radius of a mile from the church, the culprit was free from molestation.

The Borough Records of Nottingham contain numerous references to sanctuary:—A.D. 1329. John de Colston, for slaying the wife of Henry de Pek, both of Nottingham, escaped from the Town Gaol, and fled to the sanctuary of St. John of Beverley. (Vol. III. p.207.)

A.D. 1393. Henry de Whitley, of Nottingham, after slaying his wife, fled to the Friars Carmelite of Nottingham, and kept to the church, and could not be taken. (Vol. I. 255.)

In the same year John Leveret was captured at Coddington and brought to Nottingham Gaol, he having broken sanctuary, having left the church of the Friars Minor to which he had fled. (Vol. I. 257.)

The regulations as to sanctuary varied in different places. The privilege was granted in very early times, and continued, with certain modifications made during the reign of Henry VIII., until 1623, when it was finally abolished by King James I.

The ring handles on church doors, sometimes alluded to as "sanctuary knockers," are but enlarged closing rings. In a general way, both ring and pendant handles were arranged to serve as knockers also, and they were so used in the parochial processions; but the fugitive had no special need for a knocker, as he was safe from molestation, so soon as he had passed over the churchyard stile, or through the lych-gate.

The lych-gate was once a common feature; but it is now almost a thing of the past and forgotten, save that in recent years several modern reproductions have been set up, as at Bingham, Stanford-on-Soar, Sutton St. Ann's, &c. "Lic" is an Anglo-Saxon word for a dead body, its original sense being probably form. It was a funeral custom, upon arrival at the place of interment, to place the coffin upon a stone; there to await the attendance of the priest. The "coffin-stone" was about six feet long, oblong in shape, and generally narrower at one end than the other. The practice is said to have originated with the Druids. In course of time, a covered gateway was erected over the stone, in order to give shelter and protection to the mourners. The earliest reference to a "lych-gate" is dated A.D. 1272, and refers to a gate near to Gloucester Cathedral, beneath which the corpse of the murdered king, Edward II. was subsequently placed in 1327.

Another old-time funeral custom is associated with the doorway on the north side of the nave, now invariably built up with masonry. According to the ancient ritual, the corpse was carried into the church by the north door and out of it by the south door. There is also a tradition, that this door always stood open, in order to allow the evil spirits exorcised at Baptism to pass out of the church to the north side—the side symbolical of darkness and evil. There is a lack of definite information concerning the use of this door, but the inferences are all in favour of the suggestion, that its chief purpose was liturgical; and if it were possible to recall a village service say of five centuries ago, we should see the liturgical processions emerge from the church by the door on the north side, to re-enter by the door on the south side.

In early days, trial by ordeal was conducted in the church porch. Ordeal is Anglo-Saxon for "out-deal," a decision, and if we may give credence to a monkish chronicle, Emma, the mother of Edward the Confessor, on being charged with complicity, proved her innocence by walking barefoot over red-hot ploughshares, without sustaining any hurt. Be that as it may, we have it on record, that during the fifty years which elapsed between the Assize of Clarendon (1166), and the Council of Lateran, in the reign of Henry III. (1216), when it was abolished, trial by ordeal, or "the judgment of God"—i.e. an attempt to determine guilt or innocence by subjecting the accused to a test—took place in many a church porch. Usually, it took the form of handling or treading upon hot iron, or plunging the hand and arm into boiling water. It is still said of some places, Caistor, Northants, for instance, where a thick heavy door is filled with nails, that the ears and the skin of malefactors who had been found guilty of sacrilege were nailed to the church door ; but such gruesome details are now too remote for investigation.

The "trick" of trying persons suspected of witchcraft by throwing them into a pond, continued long after trial by ordeal had been abolished; for in mediaeval days, witchcraft was accounted an offence against the Church and was only punishable by the ecclesiastical courts.

1669. July 13th. "The widow Comon was put into the river to see if she would sink, because she was suspected to be a witch, & she did not sink but swim" (Archdeacon Bufton's Diary). Therefore she was held to be guilty, for, strange to say, under these circumstances it was better to sink than to swim.

During periods of internecine warfare, and especially during the Carolean civil war, many a prisoner of war faced the setting sun for the last time, as he stood for execution, against the western wall of the south porch of the parish church. A cluster of dents in the stone-work about 4½ feet high from the ground, is probably all that remains to tell of the tragedy.

(1) Towards the end of Queen Elizabeth's reign, owing to the influx of silver from South America, prices had become seriously increased while wages remained stationary. Hence among the poor, arose a period of deeper and wider distress.