That the church was used as a fortified place in early times, is beyond doubt, and there is evidence that, even as late as the 17th century, the sacred building was used for military purposes; for the heavy oak doors within the porches at Hickling and Kelham, were pierced with holes by the defenders within, to accommodate the muzzles of their muskets, in much the same way as the parapet of a modern trench is loop-holed for rifles.

It is also clear, that during these stormy periods, the soldiery did not hesitate to use the church porch as an extemporised stable, whenever necessity so required (see drawing of tomb in Arundel Church, by Joseph Nash). Nevertheless, this will not account for the iron racking-ring still to be occasionally found beside the entrance. This is a survival from 18th century pluralist days, when the parson rode on horseback from village to village, and hitched his horse at the church-door while he conducted the service within.

While these notes were in preparation, German "kultur" let loose in Europe a flood of vandalism so overwhelming, that by comparison, the happenings in English churches pale into insignificance.

The general aspect of the church porch is soon described. There is a wide archway, seldom fitted with doors, but having a gate or bar to prevent the entrance of cattle; the slot to receive the same may have been filled up, but even so, its position is still discernible; the side walls of masonry, are either solid or pierced with very small windows; there is a roof of timber and thatch, or of vaulted stone; within, a stone seat or bench-table on either side; a stoup to contain holy water; a strong inner door of plain oak boarding, relieved with scrollwork of hammered iron, or, at a later period, with elaborate tracery or panelling.

Above the outer archway (and sometimes on either side of it also), a small panel or niche was introduced. This was very plain and shallow in the early examples, but gradually increased in depth and richness of ornamentation as time went on. Within the shelter of the niche was placed an image of the patron saint in whose honour the church was dedicated; hence the expression "like a saint on a church porch." Owing to the excess of Puritan zeal which followed upon the Reformation, while the niche remains intact it is only in isolated places that the ancient images have escaped destruction. At South Scarle, for instance, an image of St. Helen still occupies the niche; and over the north porch at Balderton, there is an ancient image, probably intended for St. Giles, the patron saint.

It is pleasing to be able to record that ancient niches, which have long been tenantless, are again receiving care and attention, and in village churches, here and there, the images have been restored.

Simple as the requirements were, the porch yet gave scope for much variety of treatment, according to the period of time, and the district in which it was built. While stone was the material generally employed, it is not unusual to find, in woodland districts especially, that timber was also used.

Two fine examples, built of oak and blanched by centuries of exposure, may be found in this county. To the south doorway of the Norman church at Laneham, a timber porch was added in the 14th century. The design and workmanship are such as would be devised by a village carpenter, and all the timbers are of sturdy proportions. It has successfully withstood all the ravages of time, and still gives protection to the ancient oak door with its contemporary ironwork.

At Hucknall, also, a timber porch was added, while Thomas Torcard was vicar (c. 1320). It was built on a stone plinth, and had a thatched roof. In 1872, this porch was carefully taken down and refixed, stone by stone, and timber by timber, in its present position. The thatched roof was not replaced, but the original timbering with the exception of the renewed barge-board, and the entrance door, with the slots for a fastening bar still remain.

From the 14th century onwards, wooden porches were in vogue, having sides of elaborate screen-work; but I have not met with any examples in this county. After the Reformation, many porches were rebuilt in plain brick-work (Edwalton); in some cases, a sundial painted on a board, was fixed in the gable, in place of the image niche. (Orston, previous to recent restoration.)

The porch made its appearance in England, at an early date. The church which Bishop Wilfrid built at Repton (c. 670), is said to have been "built of polished stone, with columns curiously ornamented, and porches." These would be in reality, but little more than deeply recessed doorways. If any Saxon porches were built in this county, no traces of them remain. Of 12th century porches, the earliest workmanship is contained in the north porch at Balderton. Several interesting points for study are here presented. To begin with, the outer gate was obviously once an inner doorway. It would appear that in the 13th century, the north doorway was taken out and reset in a forward position, so as to form a porch; but contrary to prevailing custom (see Norton Cuckney), the added work in niche, gable coping, and cross, was made to harmonize in style with the earlier work. Again, it should be noticed, that, unlike all others in the county, the jamb shafts are enriched with beaded cable and chevron, after the manner of the west doorways at Lincoln. The reason for this is not far to seek, for Balderton lay in the manor of Newark, which Countess Godiva gave to Remigius, the first Norman bishop of Lincoln; and Newark became a favourite place of residence for the bishops, especially after the princely Alexander had built his castle there. And so while all other Norman work in the churches of the county follows York traditions, the porch at Balderton favours Lincoln. In addition to enrichments on the shafts, the inner order of jamb and arch, carries the beak-head moulding, the intermediate order triple chevron, the outer order single chevron, and the hood moulding a triple row of billets.

Of the later Norman period, the north porch at Southwell, is perhaps the finest of its class in England, and is in many ways unique. It occupies the third bay from the west end, and being of spacious dimensions, it gives importance and interest to the church, when viewed from the north-west. It is a fair assumption, that generation after generation of Nottinghamshire folk have offered their Pentecostal gifts within its walls; for the Whitsuntide Processions were revived so soon as the rebuilding of the mother church had been completed (c. 1150). The White Book of Southwell (p. 124), contains a letter written by Thomas, Archbishop of York (1109-1114), addressed to all his parishioners of Nottinghamshire, praying them to "assist with their alms to the building of the church of St Mary of Suwell." The letter goes on to say, that they are "bound the more readily to do this, inasmuch as he was releasing them from the annual visitation to the church of York, incumbent upon all his other parishioners, & was allowing them to visit the church of St Mary of Suwell instead." By a decree of the Pope (Alexander, 1171), it was ordered that every year, both clergy and laity of Notts, should, at the Feast of the Passover, attend at the church at Southwell, in solemn procession, with a Pentecostal offering from every parish and hamlet in the county.

This order was ceremoniously obeyed for 600 years at least, and the picturesque, many coloured processions of the past lingered on until late in the 18th century. Deering writes (1751):—"The Maiore of Notttinghm & his brethren, & all the clothing likewise to ride in their best livery, at their entrance into Southvil, on Wytson Monday, & so to procession, Te Deum; without the Maiore & oder think the contrary, because of foulness of way, or distemperance of weder; also the said Maiore & his brethren, & all the clothing in likewise to ride in their livery when they be comyn home from Southvil in the said Wytson Monday, through the town of Nottinghm & the said Justice of Peace to have their cloakes borne after them on horse back at the same time through the towne." Numerous entries of expenses in connection with these visits appear in the "Borough Records."

The details of this porch have been frequently described. The salient features are a wide plain-moulded semi-circular arch, which springs from the horizontal string-course, decorated with the chevron or zig-zag ornament, which ran all round the exterior of the Norman church without a break, and was continued both inside and outside the porch, thus forming the abacus to the sturdy respond-shafts and the impost for the springing of the barrel vault. Below the string-course, the internal walls are faced with a double arcade of semicircular intersecting arches. A plain string-course crosses the face of the porch at the level of the eaves, and in the low-pitched gable above are three round-headed windows, which give light to a snug little chamber over the porch. This chamber is approached from the triforium passage, from whence all parts of the church are accessible. The gable is flanked by circular pinnacles, and the one at the north-west angle contains the flue from a corner fire-place in the chamber.

The Latin designation "domus inclusi" implies that this chamber was "the dwelling of one enclosed within the church," one whose duty it was to ring the bells, and to keep the lights burning before the altars. In A.D. 1294, Archbishop John Romanus ordered "a sacrist to be within the church of Southwell, to ring the bells of the appointed hours."

Barnaby Googe, not always a safe guide on English church usage, may yet be quoted. Writing of the Anniversary of the Day of Dedication of a church, he says :—

"All others voided from the church that thus shall hallowed be,

The Sexton only there remains enclosed secretly."

(Barnaby Googe, fo. 12. A.D, 1577.)

In 1643, while Cromwell's troopers were in possession of the church, William Clay the Registrar of Southwell, successfully hid his wife in this little chamber, and while she was in hiding, their daughter Joan was born.

The only other example of a Norman porch-chamber in England, is the contemporary north porch of the church of St. Giles, at Bredon, Worcestershire, which follows on the same general lines as Southwell, but is not nearly so elaborate in detail.

South porch, Holme.

We shall have to leave the Norman period, and bridge over three and a half centuries, before we find another church in this county with a loft or anchorage above the porch. At Holme, near Newark, an extension of the village church was made in the 15th century, comprising a new chancel with side chapel, south aisle to the nave, and a south porch with a chamber above it, approached by a spiral stair-turret in the north-west angle.

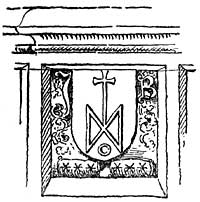

At this period, it was not at all unusual for the patron to decorate a new porch with heraldic insignia (see also Linby), and so, at Holme, we find a row of (seven) armorial shields, which stretch across the front of the porch, between the apex of the doorway and the drip-mould beneath the loft window-cill. These display the arms of the Bartons and their alliances.

The will of John Barton is still preserved in the Castle Museum at Nottingham, wherein he directs his body to be buried "in my new tomb in the chapel recently constructed by me at Holme." The will is dated 10th December, 1490, and this gives us the approximate date of the porch. John Barton was a well-known merchant of the staple of Calais. The 5th shield1 from the west carries his initials and merchant's mark.

When Newark and its neighbourhood was ravaged by the Plague, in 1666, this chamber also became the domicile of a recluse, in a different sense from the original one, as the following extract from Dickinson's History of Southwell" (1801) will shew. "Over this porch is a chamber, called as far back as memory or tradition reach 'Nan Scott's Chamber.' - - - The last great plague which visited this kingdom is reported to have made particular havoc in the village of Holme. - - -During its influence, a woman of the name of Ann Scott is said to have retired to this chamber with a sufficient quantity of food to serve her for several weeks. Having remained there unmolested till her provisions were exhausted, she came from her hiding-place. To her great surprise, she found the village entirely deserted, only one person of its former inhabitants except herself, being then alive. Attached to this asylum, & shocked by the horrors of the scene without, she is said to have returned to her retreat, & to have continued in it till her death at an advanced period of life."

From this 17th century tradition of Nan Scott, who if not the last, was contemporary with the last person who found habitation within the church in England since the Reformation, right back to within half a century B.C. when, according to the sacred drama, Judith, the reputed patroness of all ankeresses, secluded herself in her own house for three years and four months, after her husband had succumbed to sunstroke in the barley-field of Bethulia, a host of women and of men not a few have sought in seclusion a shield from the "world's volubility" and sorrow. Unlike the hermits, who loved freedom and solitude, and quite apart from the practice of monastic seclusion, ankerites always favoured the vicinity of Holy Church. A little chamber, plastered on to the walls of a church like a swallow's nest (see the Life of Dame Julian of Norwich in the 14th century)—a chamber in the steeple (Upton)— a vestry chamber on the north side of the chancel (Gedling and Hawton)—a chamber above the vestry (Lambley)—or a loft over the porch (Holme)—each in turn has been made to serve the purpose. In some instances, the chamber was furnished with a piscina, which proves that it was intended for a clerical occupant; in others the presumption in favour of a cleric is very strong, but in not a few cases such chambers are known to have been occupied by lay recluses, male or female, until the Reformation came, when they were either swept away, or converted into libraries, parish muniment rooms, &c.

"I would have thee build

Such a room for him, as our Anchorites

To holier use inhabit.

Let not the sun

Shine on him till he's dead."

Webster. Duch. Malfi. iii. 2.

(1) Argent : two triangles meeting by their apices in the centre of the shield, from which issues a cross patae ; and at the base an annulet Sable. Below are two wool-sacks, each charged with three estoiles of six points in fesse. At the side of the shield are the initials J.B.