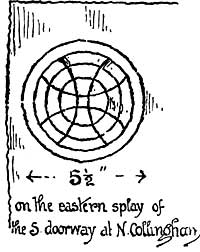

It is no unusual thing to find a cross, or a number of crosses (at Egmanton there are fifteen) cut in the eastern jamb, or on the wall near to the doorway. It is difficult now to determine for what purpose they were made, and many wild and random suggestions have been put forward. They are a survival of a very primitive custom, and recall the Scriptural words:—''This stone shall be a witness unto us." Joshua xxiv. 27. They were used to record a vow of seclusion, or a vow made at the commencement of a journey, to give an offering to Holy Church on the safe return. Just as Jacob put up a pillar of stone to record his vow:—"If God will be with me, & will keep me in the way that I go, & will give me bread to eat & raiment to put on so that I come again to my father's house in peace; then shall the Lord be my God" (Genesis xxviii. 20, 21.) Or they may have been made at the consecration of that part of the church.

We must now hark back again, in order to consider the chronological development of doorways. The remains of pre-Conquest, and early Norman doorways are very fragmentary. From them we may learn that the top of the doorway was invariably square, with a round arch above it. The tympanum, i.e. the space lying between the lintel and the intrados, or enclosing line of the arch, had either a plain stone face Linby, (North door), Maplebeck, Hockerton, or it was rudely incised (Everton), or more generally it served as a "Poor Man's Bible" (Biblia Pauperum) in bas-relief, the favourite subject being an allegorical representation of the unceasing conflict between Good and Evil, typified by the Archangel Michael, in combat with a fearsome Dragon, in the presence of the Lamb. The church of St. Michael at Hoveringham, rebuilt in 1885, retains the head of the doorway of the original church. Writhing dragons are entwined across the lintel, the ends whereof serve as springers to the arch stones, and are rudely sculptured with standing figures of St. Peter on one side, and a Bishop (unknown) on the other. On the tympanum, the conflict between St. Michael and the Dragon is rendered with a vigorous realism, mediaeval in its grimness.

A fragment of a very similar door-head is built into the wall of the north transept, at Southwell, and the remains of sculptured tympana are also found at Hawksworth, Kirklington, Carlton-in-Lindrick, and in the porch at Broughton Sulney.

Late Norman doorways are fairly numerous, especially in the neighbourhood of Southwell, where all the prebendal doorways are fine examples of the period.

Speaking generally, Norman doorways have semicircular arches, in receding orders of mouldings, which are often profusely enriched. Exceptions to the rule, are found in the south door at Southwell, which for obvious reason has a segmental head, and the south chancel door at Halam, which has a pointed head ; but the latter may be only a patchwork insertion.

Of enrichments, the chevron or "zig-zag," the latest in point of time, is by far the most prevalent in Notts. At Southwell, the skilled masons found the fine-grained magnesian sandstone exactly to their liking, and the mouldings were consequently kept small in scale, and impress the beholder by the regularity and profusion of their zig-zag lines. In village churches, where only indifferent local material and local talent were at command, the work was apt to be clumsy and irregular. It would seem to have been a recognised custom, to make the points of chevron, coincide with the joints of the stone. Where large blocks of stone were available, each capable of holding several patterns (Southwell), this did not matter so much: but when the rule adopted, was two points to one stone (Cuckney), or only one point to one stone (Balderton), regardless of the size of the block, much irregularity ensued. In almost every case where chevron is employed on the inner order, it is continued to the cill, without any intervening impost.

A little earlier in date is the beak-head, which occurs in the doorways at Southwell, Balderton, and Winkbourn; and the double-cone, at Southwell, Woodborough and Cuckney; while the earliest of all the enrichments, the billet, which appears to have been confined to hood-mouldings, is found at Southwell, Balderton, and Rolleston.

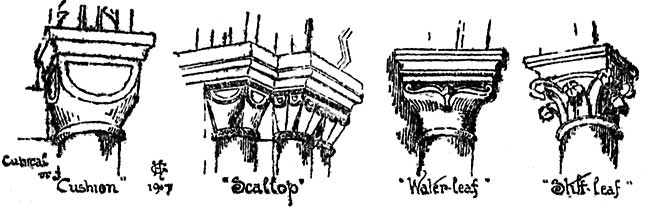

The jamb-shafts, (with the exception of Balderton already noticed,) are all plain, and surmounted by cushion capitals, which shew much variety of treatment. The earlier and simpler form was a plain stone, shaped like a bowl, truncated to conform with a square covering slab, or abacus. As time went on, the size of the truncated cone was decreased, and the number increased, so that each face of the capital held not one only, but a pair, or eventually a larger number of scallops. Each scallop, at first left plain, was afterwards painted, or it became a field for rude sculpture, and carved ornamentation, bewildering in its diversity, while yet exhibiting many points of likeness common to all of them.

Norman doorways remain to the following churches:—

Southwell:—c. 1150. North doorway:—five jamb shafts, six orders of arch-moulding, of which one is plain, one has beak-head enrichments, and all the remainder a dazzling array of chevron.

West doorway:—four jamb shafts, five orders of arch-moulding alternately plain and enriched with chevron, with a double row of billets on the hood-moulding. South doorway:—two jamb shafts, three orders of arch-moulding enriched with chevron, and a chevron stringcourse rises over the arch as a hood-moulding.

Woodborough:—c. 1150. A doorway, once the main entrance to the church, is now out of use and built into the north wall, three jamb shafts, three orders of arch-moulding enriched with chevron, double-cone and beaded cable.

Lanbham:—South doorway has double jamb-shafts, two orders of arch-moulding enriched with chevron, plain hood-moulding.

Balderton:—c. 1140. South doorway :—the arch-moulding carries one order of single chevron, two of double chevron, with semi-circle and billet on the hood-moulding.

Winkbourn:—South doorway:—one continuous order of beak-head in varying sizes; plain hood-moulding with long head terminals.

Norton Cuckney:—South doorway:—two continuous orders of double chevron, and one of double cone; plain hood-moulding, with long head terminal. Edingley:—West doorway:—two orders of chevron, with cable and nail-head on hood-moulding, with long head terminals.

Elston Chapel:—Said, upon what authority I know not, to have been removed, stone by stone, from East Stoke, in the 16th century; has a south doorway with continuous chevron on the inner order.

Traces of chevron are also found at West Drayton, and Cottam.

Small doorways of a plainer type remain to a number of churches in the county. These consist of plain mouldings or simple chamfers, which carry no enrichment, save perhaps that the hood-moulding terminates on a long head corbie, fashioned with beaded lines into the semblance of a head of a monster dragon. The west doorways at Plumtree and Mansfield, south doorways at Norwell, Wysall, Harworth, Carburton, south chancel doorway at Edwinstowe, north door (built up), at Attenborough, &c. are examples. They are all of early type and belong to the Norman or Transitional periods; but they are somewhat difficult to classify with precision.

During the Transitional period in the long and peaceful reign of Henry II. (1154-1189), semi-circular arches were at first predominant, but they began to give place to pointed arches, and "nail-head," and the early form of " dog-tooth " ornaments began to appear. The finest doorways in the county of this period, are the great western doorway, and the north doorway at Worksop, where in addition to chevron and cable enrichments, the nail-head and dog-tooth are profuse on arch-moulding and jambs; but owing to extensive restorations, very little of the original work remains.

South Leverton:—c. 1180. South doorway:—three recessed orders of arch-moulding, the inner order carries on face and soffit, a form of chevron enriched with leaves. At this time, a marked development of the capital took place, for the cushion gave place to an inverted bell the rim whereof broke into broad leaves, with an incurved volute at each extremity, to give support to the overhanging corners of the abacus, which still remained square on plan. This has come to be known as the "water-leaf" capital. It prevailed 1165-1190.

Sturton-le-Steeple:—A very similar doorway, minus the chevron enrichment (both these doorways are illustrated in Vol. XIII.)

Carlton-in-Lindrick:—The south doorway was removed when the aisle was added half a century ago, and reset in the western face of the tower. The inner arch has single chevron continuous to the cill; the next order has chevron on face and soffit, the remaining two orders and the hood have plain mouldings. The triple jamb-shafts have foliated capitals with the exception of the outer ones, which have out-curved volutes. North Leverton:—South doorway in three orders, similar to South Leverton, but with "dog-tooth " enrichments.

At Darlton, a south doorway has detached jamb-shafts, with water-leaf capitals, and a plain arch-moulding, having bold outstanding dog-tooth ornaments on the hood-moulding. There is a similar doorway at East Drayton. The inner doorway of the south porch at Selston (c. 1199) has a plain arch-moulding in three orders, and two rows of dog-tooth ornament between the triple jamb-shafts. This doorway presents some curious features which point to its having been rebuilt.

But perhaps the most curious example of reconstruction to be seen in this, or any other county, is the south doorway at Teversal, which appears to have been built up with Norman materials, probably taken from the west end of the original church. The arch is in two square-edged orders. The face of the outer order is enriched with the "sunk-star" ornament, which is carried some distance down the jambs, when it is interrupted by the insertion of some old cap stones. No reasonable explanation has yet been made to account for the fact that not only are these jamb stones fixed upside down, but two capitals are carved on one stone, the one immediately above the other. I am puzzled to account for this phenomena, and like other writers before me, I simply record it with an admission of my perplexity. A series of pateras, or medallions, are carried round the inner order of the arch, and down the jambs, containing emblems of the patron saint (Catharine) and other symbols. The curious patchwork of this doorway, is equalled by the curious door. I am of opinion that the foundation of the door, and the iron strap-hinges and scrolls, pertain to the 12th century, and that the door was strengthened at a later date by the addition of a chamfered frame and muntins, which were superimposed, and nailed on to the old plank door, while in situ; hence the irregularities in the workmanship.

All the before mentioned doorways have semicircular arches. A disused1 western doorway at Gedling which has jamb-shafts with water-leaf capital, and pointed bowtell in the arch-moulding, has nevertheless a pointed arch, and from this time onwards, the pointed arch prevailed.

A spacious south porch was built at Blyth c. 1180, and rebuilt in its present position when the south aisle was enlarged, c. 1287. The twin jamb-shafts have the water-leaf capitals, but what most impresses the beholder is the large equilateral pointed arch, in three orders of deeply undercut plain mouldings. Its proportions are now somewhat marred by an embattled parapet, added in the 15th century, when that form of roof became common in the district. At Norton Cuckney, an original Norman porch was partly rebuilt in the 13th century, and thereby lost some of its character.

The western portal at Thurgarton Priory (founded 1140 and rebuilt in the 13th century), is perhaps as fine as anything of the same period in England. The central doorway has eight jamb-shafts on either side, but they are set in a row on the widely splayed face of the jamb, and not in receding orders, after the usual manner. The capitals are entirely composed of plain mouldings, and the necking, bell, and abacus, are all circular on plan. The deeply undercut arch-mouldings lie on rectangular planes, with dog-tooth ornaments in the hollows. The north-west doorway in the tower is a small replica of the same design.

The north porch and inner doorway, have been rebuilt, and the capitals and the arch stones of the entrance, and part of the voussoirs of the arch of the inner doorway are perhaps the only original work which remains; but all the proportions are exquisite, and the mouldings are deeply undercut and enriched with dogtooth ornaments.

(1) Since this paper was written the doorway has been opened out, repaired, and fitted with a new oak door, in memory of an officer who fell in the great war.