< Previous | Contents | Next >

An itinerary of Nottingham

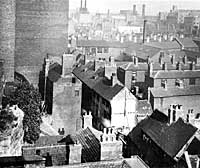

Narrow Marsh

View over Narrow Marsh in the 1920s. Much of the area was demolished in slum clearance schemes during the 1920s and 1930s.

ONE hardly recognises Narrow Marsh under its modern name of Red Lion Street which was bestowed upon it in an access of zeal in 1905. I think the authorities must have come to the conclusion that the cup of wickedness of Narrow Marsh was full, and that the very name had something unholy about it and so they thought that by changing the name they could change the character of the inhabitants. Well, their intentions no doubt are very praiseworthy, but in attempting to get rid of the name of Narrow Marsh they have attempted to destroy an extremely interesting relic of the past, and in spite of the official and very prominent notice board displaying the brand new name of Red Lion Street, the name of Narrow Marsh holds its own pretty firmly to-day, and this is not to be wondered at. It is the natural name of the thoroughfare situated between the river Leen and the foot of St. Mary's cliff, and it has been called Narrow Marsh with an astonishing variety of spelling ever since 1315, or the year after the battle of Bannockburn. In those far off days it was called "Parvus Mariscus," "The little marsh," and rather dignified it looks in its cloak of Latin. It was part of the route from south to north, thrust aside by the fortifications of Edward the Elder's burgh and also perhaps is one of the oldest thoroughfares in Nottingham. Its age is very great and it must have existed for centuries before its debut into history in 1315. Its physical features are, of course, the great 70ft. precipice which overhangs it on the north, and the river Leen which alas ! has now vanished, on the south. It was of extreme importance as a business thoroughfare during the earlier part of the middle ages, and in fact, right down to the general introduction of wheeled traffic in the 17th century it was, the main commercial street of Nottingham. Traffic passed along it and up Drury Hill, through the Postern Gate into Bridlesmith Gate and so onward to the north. We get corroborative evidence of this importance of Narrow Marsh as late as 1523. In that year a subsidy was called for, a sort of tax to which practically everybody had to contribute, and the roll has come down to our own days wherein is inscribed the different amounts which had to be raised by each street in Nottingham. The total sum collected for the whole town was £50 6s. 8d., which would probably be worth somewhere near a thousand pounds nowadays. Of this sum Low Pavement was assessed for £9 5s. 0d. the highest amount apportioned to any street. Narrow Marsh was assessed as the next most important street and had to bear £7 13s. 2d. I need not trouble you by giving you the full list of the streets of Nottingham, but it is interesting to notice that Long Row, which we should consider by far the most important street in Nottingham only had to contribute £2 9s. 6d. in those far off days.

As Narrow Marsh was so busy and important a thoroughfare the frontage to it became exceedingly valuable, the result is that it is laid out in long narrow strips, with their narrow ends towards the busy thoroughfare. These narrow strips of course had to have a back lane to admit of access to their rear and this lane has come down to us as Leenside, while the narrow strips are represented by the curious courts and alleys which join up these two roads. This type of lay-out is always regarded as extremely early and it is paralleled in only one other place in Nottingham, and that is upon Long Row which presents the same phenomena of narrow frontage, long, thin strips represented by courts and alleys which join up into the back road which is nowadays called Parliament Street. These courts and alleys are reminiscent of the Wynds of Edinburgh, the Rowes of Yarmouth, and other similar passage-ways in ancient towns. The late Mr. W. Stevenson was of the opinion that Narrow Marsh was considerably older in date than Long Row and he went so far as to advance the theory that it represented a pre-Conquest estate belonging to the priest of Nottingham. Domesday Book refers to the fact that "In the croft of the priest there were sixty five houses," etc., which the king retained in his own hand, and Mr. Stevenson thought that these sixty-five houses are probably represented by the scores of houses in and about Narrow Marsh nowadays. It could never have been a very pleasant place of residence in spite of its extraordinary prosperity. A horrible miasma arising from the swamps of the Leen must, one would have thought, have been conducive to ague and rheumatism and other unpleasant diseases. Moreover, we know that it was constantly being flooded: for example, in 1795 and again in 1809, flood water reached it and rendered it difficult for traffic to pass. But in spite of it all it has always been a populous district and, curiously enough, as if to comment upon hygienic science and research, there are even to-day, half-a-dozen fig trees blossoming and fruiting on the filthy cliff which overhangs the chimneys of the houses below it. It is an interesting fact to remember that the last thatched house in Nottingham stood somewhere in Narrow Marsh. I cannot place the exact site but in 1854, it belonged to the Rev. James Hine.

Narrow Marsh formed, together with its back land and the street accommodating those lands, the southern outskirt of Nottingham before the enclosure of the last generation. The streets south of Leenside were not formed until after 1751, when the country had begun to settle down again after the alarm caused by the Jacobite rebellion of 1745.

Let us now make a tour through Narrow Marsh and see what we can find to interest us and to tell us of its extraordinary past. The first street we come to on the southern side is Pemberton Street which is largely composed of houses built in 1848 by the Plum tree Trust. On their facade is the Plumtree Arms "Argent, a chevron between two mullets pierced in chief and an annulet in base sable" below which is the motto "Sufficit Meruisse." A few yards beyond this street is the inn called the "King's Head." Now, this "King's Head" has attached to it a most entertaining history, for it was a resort of the romantic Dick Turpin. What we know about Dick Turpin and his dealings with Nottingham is contained in a little pamphlet published in 1924 by Mr. Louis Mellard. It is a series of extracts from a diary kept by a Lincolnshire farmer, whose name is suppressed but who goes under the title of "Tobias 'K'". Tobias appears to have been much occupied in living a double life. He was a respectable farmer doing rather well somewhere near Lincoln, but part of his time seems to have been occupied in acting as a purchaser of stolen goods from Turpin and other "horsemen" as they were euphemistically called in those days. The "dramatis personae" of the comedy staged in Nottingham consisted of Tobias and Turpin himself and a gentleman called Alfred Coney who appears to have been a man with pretension to some good birth but an out and out bad lot. He acted as an agent for many highwaymen and succeeded in disposing of their ill-gotten gains for them. Coney lived at the "Loggerheads," an inn on the other side of Narrow Marsh to the "King's Head," a little further west, and his companion was a lady of the name of Martha who is described as "once a good looking wench, too good for that ugly, fascinating devil Coney." I think she must have been his wife and loved him in spite of his terrible record for there are many instances of her faithfulness to him. Martha and Coney had amongst their numerous circle of friends, a couple who lived just behind the "Loggerheads" who went by the delightful titles of "Bouncing Bella" and "Lanky Dobbs." "Lanky Dobbs" was ostensibly a chimney sweep by profession, but in reality he was a most excellent and useful spy, for in pursuing his respectable occupation he had numberless opportunities of discovering where the "stuff" lay and how to get at it. Coney himself was not a burglar, but he had at his beck and call numberless gentlemen who were prepared to act for him. He appears to have reduced the whole thing to a science of whistling. A certain note meant that a burglar was wanted, another note that a pickpocket was required and so forth, and one can imagine that a shrill whistle from the windows of the "Loggerheads" in the middle of the 18th century would produce quite a lot of candidates for whatever job might be on hand. It is worth remembering that a gentleman called "Slimmy" seems to have been regarded by his confreres as the most expert and accomplished burglar of Nottingham in those days.