< Previous | Contents | Next >

Bridge over the Nottingham Canal (photo: A P Nicholson, 2004).

But the canal system really was of inestimable benefit before the days of railways. As far as Nottingham is concerned we were joined up to Grantham and Lincolnshire by the opening of the Grantham Canal in 1797, the year in which the battle of Camperdown was fought, while the Erewash canal connected the Trent with the enormously important Cromford Canal in 1777, the year in which Saratoga surrendered. Indeed, canal traffic was so important that even after railways were established extensions were made in Nottingham, and the canal joining Poplar with Sneinton Hermitage, which provides so much dock space, was constructed in 1835. It is interesting to notice the bridges over the canal by the side of London Road. They are stone-built structures and they are of course a hundred and thirty three years old.

Proceeding down London Road from Trent Bridge one passes on the western side Ryall Street, which I think is a corruption of "Royal Street" for thereabouts were erected fortifications during the struggle between Nottingham men and the Newarkers during the Civil Wars, which were called the "Royal Hills" after King Charles I. They have of course completely disappeared and the street has recently been christened Ryehill Street.

Burton Almshouses in the 1920s. They were demolished in the 1950s.

Burton's Alms Houses were established by Miss Ann Burton, in 1859, as the date-stone shows. She lived in Spaniel Row and erected these Alms Houses for the accommodation of twenty-four widows, widowers, or unmarried persons over sixty years of age in needy circumstances, and of whatsoever religious persuasion they might belong. Her father was a prosperous saddler. She inherited his fortune and being of very quiet tastes she spent little money and her income accumulated until she was very wealthy. With a portion of her money she established these Alms Houses and drew up a will disposing of the remainder of her fortune, but a sudden seizure proved fatal and her will was never signed so that a very much disliked cousin came into a large and unexpected fortune.

The cattle market was opened about 1880 and is exceedingly well fitted and well accustomed. Queen's Road gets its name in rather a curious manner. In 1846 Queen Victoria and Prince Consort had been staying at Chatsworth and they were proceeding to Belvoir Castle. The railway of course was only open in those days as far as Nottingham and so Queen Victoria and her husband had to leave the train at the terminus, which is now the goods yard in Carrington Street. They stopped for a little time interviewing the important officials of the town and finally entered their carriage and drove down the new road which was in process of formation across the West Croft and whose completion had been hastened for the occasion. As Queen Victoria was the first person to pass over it, it was christened Queen's Road in honour of the event.

Under Leen Bridge was placed one of the public baths of the town for in addition to the one at Trent Bridge already mentioned and another at St. Anne's Well, the only accommodation for bathing in Nottingham at the time Blackner published his history in 1815 was under Leen Bridge and a very small establishment between Leenside and the canal, opposite to Navigation Row. As private houses were rarely fitted with baths it is rather unpleasant to think of the condition our forefathers must have got into.

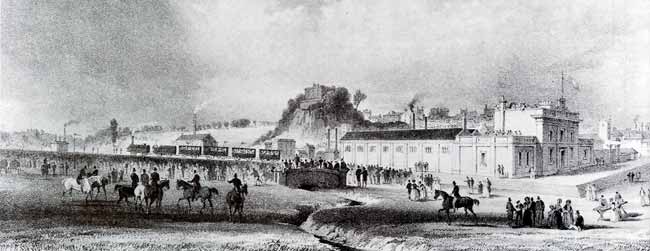

The first train leaves Nottingham for Derby, 30th May 1839.

In 1846 The Nottingham and Lincolnshire railway was opened and the old railway from Derby was extended across Carrington Street to join up with the new line. A new station was built in Station Street which remained in use down to 1904. It was completed in 1848, and the street leading down to it was christened Station Street. It is rather interesting to remember that in Station Street Messrs. Hine Mundella & Co., established the first steam-driven hosiery factory in Nottingham so recently as 1851. The London and North Eastern Low Level station with its attendant yards are of curious genesis. It was erected in 1857, the year of the Indian Mutiny. It was a time of sad depression in Nottingham and work was scarce. The authorities therefore eagerly accepted the Company's offer to take soil from Woodborough Road to form a huge platform raised above flood level upon which to erect their station and sidings. The site from which the soil was taken was on the hill leading up to Mapperley. In 1632 Fox Lane is mentioned as extending from what is now Mansfield Road to Sandy Lane, the modern Huntingdon Street and Windsor Street. The lane then became a mere cart-track called Goose Wong or Goose Meadow Lane, which led up the hill and was closed by a stile about where Cranmer Street now enters Woodborough Road. From there a footpath led by the side of the Tode Hole Hills, meaning of course the Fox Hole Hills, for "tode" or "tod" is an ancient name for fox, and joined Red Lane about where Alexandra Park now stands. This track was put into good order by unemployed workmen and the surplus soil was accommodated by the Great Northern Railway Company, and the town was tided over a period of grave unemployment. Previous to the construction of this thoroughfare, the way to Mapperley had been via St. Anne's Well Road, or via Redcliffe Road which used to be called Red Lane, and which in addition to its appalling gradient was on clay and was practically impassable for a good part of the year.

St. John's Schools were erected in 1846 and almost directly opposite is Island Street, which is now so much occupied by the great works of Messrs. Boot as to have become almost a private road. Island Street had its dramatic day in 1848. At that time the Chartists were very threatening and the authorities were on the look out for riots. They made huge preparations swearing in no fewer than sixteen hundred special constables. It was feared that the first assault would be delivered upon the gas works which were then situate in Island Street, so they were garrisoned by a large number of workmen and provisioned to stand a siege. Huge chains were stretched across the street to prevent rushes and the walls were re-enforced and loopholed for rifle fire. Fortunately the preparations had a calming effect upon the hotheads and no riot took place.

The Crown & Anchor Inn was the starting place of one of the many post-gigs which ran out of Nottingham. These gigs differed from the ordinary mail coaches, for while carrying letters and parcels, they were forbidden to carry passengers. The gig from the Crown & Anchor left at 6.30 each morning for Derby. It must have been a very inconvenient system to have gigs and other conveyances starting from inns all over the town instead of making a general rendezvous at the Post Office.

And now we come to Plumtree Square and the reason for this square is now perfectly obvious for we have seen that the ancient road was set a little bit to the west of the present London Road, aiming, in fact, for the foot of Malin Hill. The newer road was placed by the side of it and became the main thoroughfare. As the old road was gradually abandoned encroachments were made upon its surface, but this little bit of the old double width road has remained to our own day.

St. Patrick's Roman Catholic Church was erected in 1880 at a cost of £6,000 and the reredos contains panel paintings of the Blessed Virgin, St. Patrick, St. Joseph, St. Anthony and St. Winifred.

Before we leave London Road it would perhaps be as well to consider the condition of roads during the middle ages for they were far from being the smooth surfaced well kept thoroughfares to which we are accustomed. Within the confines of the town of Nottingham, drawings so late as the 18th century show that it was necessary to place stepping stones to get across the mud, even in the most important streets, and if such were the conditions that obtained in the heart of a busy town what must the roads have been like in country districts?

The Romans indeed left us a fine system of well engineered excellently paved roads, but after the departure of the Roman government at the commencement of the 5th century there was no provision whatever for the upkeep of the roads except a few sporadic charities. They were utterly neglected and became mere tracks extending at times over quite a wide strip of country as passengers passed from side to side endeavouring to find firm foot hold. They were often overgrown with brambles and bushes, they were impeded by ruts and streams meandered about them at their own sweet will and worse than that, they were the haunt of foot-pads and cut-throats. We can get some reflection of the condition of mediaeval roads in the fact that when Alan of Walsingham, the architect of Ely Cathedral desired to bring great logs from the forests of Norfolk to his church in 1322, the first thing he had to do was to construct a road which took four years to settle sufficiently to carry the weight of the logs. Again after the dissolution of Jerveaux Abbey in Yorkshire in 1547 it was found impossible to remove the lead from the abandoned buildings for six months or more for the roads during winter were so foundrous that no waggons could be dragged over them and the transaction had to remain until the summer had dried and hardened the roads. It was not until Macadam who was appointed surveyor to the roads round Bristol in 1816, hit upon the idea of covering roads with stones broken to pass a two inch ring that the modern system of road construction came into force, and it is due to him and to such experts as Blind Jack of Knaresborough that we owe our present excellent road system.