< Previous | Contents | Next >

The north east corner tower dates from c.1270 (A Nicholson, 2001).

Edward IV. was very partial to Nottingham and it was here that he was first proclaimed King in 1461. All through the Wars of the Roses, Nottingham remained Yorkist and the banner of the White Rose was displayed from the Castle. Edward IV. very much enlarged the castle. He took in the lower bailey, where now the bandstand is erected. All this was defended by an outer dry moat which is represented to-day by Castle Road and by walls and bastions, predecessors of the modern restorations. It was entered by the gateway which still remains in a restored condition and which was probably erected about 1470. In addition to all this Edward IV. commenced the great tower which was nicknamed "The Castle of Care" from the vast amount of care he took over it, and whose foundations are still visible in private grounds in Castle Grove. He had only carried this tower up for three stories when he died and was succeeded by Richard III. who was equally attached to Nottingham and who completed the Castle of Care, probably with wooden stories. Richard spent a considerable part of his short and stormy reign in Nottingham Castle and it was from it that he set forth in 1485 to Bosworth and death.

The Tudors realized that strongholds in private hands were a menace to the peace of the realm and so they set their faces against castles and they were gradually allowed to fall into disrepair and to become uninhabited. Nottingham Castle shared this fate to a great extent, for when Leland visited Nottingham in Henry VIII.'s reign, he found that the castle was in a state of disrepair.

Tradition has it that Cardinal Wolsey spent a night in Nottingham Castle on his way to Leicester after his arrest in 1530, but I think that if he slept in Nottingham at all it would be much more likely to be at Lenton Priory.

The castle had become so ruinous by James I.'s reign as to be of little military value and in 1603 it was granted by the King to Francis, Earl of Rutland. However, its stirring days were not yet over and in 1642 it was made the rendezvous of the Royal forces, although it was so ruinous that Charles I. was fain to sleep in Thurland Hall. On August 22nd, 1642, the Royal banner was unfurled on the top of the Castle of Care, but a violent gust of wind blew it down and it was re-erected just outside where St. James's Church now stands. Since Henry VIII. had established a standing army private banners had gone into disuse and the nation fought under the national banner made of the crosses of St. George and St. Andrew. As Charles's action divided the nation, he reverted to the ancient custom of a personal banner. These banners were usually formed from the livery colours of their owner, and in addition to the cross of St. George, they bore the War Cry, Arms, Supporters and Crest of the leader. There is a replica of King Charles's Banner shown in the castle. It is a large red streamer with cloven end.

Next the staff is a St. George's Cross, then the Royal Arms with a hand pointing to the crown and the legend "Give unto Caesar his due," then two other crowns each surmounted by a lion passant.

Charles left Nottingham on September 13th, 1642, and the castle was immediately occupied by Parliamentarian forces. Mrs. Hutchinson describes it as being "very ruinous" and goes on to give details as to its condition. These details do not contain much of interest except the fact that there was a spring of water "on the top of all the rock." This seems an extraordinary statement and I can only suppose that she had a well in mind. Colonel Hutchinson and his men put the castle into some sort of repair and held it all through the Civil War, although they were never called upon to repel any very serious assault. Of their occupation few traces remain, but to them are probably due the reparations to the gatehouse carried out in red brick.which are still noticeable. The castle was dismantled in 1646, much to Cromwell's annoyance as he had apparently hoped to keep it in his own hands and use it for his own purposes, but was forestalled by Hutchinson's loyalty to the Parliament. Its strength, however, in some sort remained until 1651 when it was completely wrecked, probably with the assistance of gunpowder by Major Thomas Poulton acting under orders from Parliament.

For twenty years it remained a desolation and then in 1671 it was bought from the Duke of Buckingham who in 1664, four years after the Restoration, had inherited it in the right of his mother, sole heiress of the Earl of Rutland, by William Cavendish, first Duke of Newcastle and grandson of the famous Bess of Hardwick. Cavendish was a typical Renaissance nobleman, ostentatious and greedy of honours and yet cultured and intensely loyal. At the outbreak of the Civil War he had been made commander of the King's northern forces and had met with considerable success, but after the defeat at Marston Moor he went into voluntary exile in Hamburg for eighteen years where he was much occupied by his favourite pastime of horsemanship, publishing in fact several treatises on the subject. He returned to England soon after the Restoration and immediately commenced the restoration of his ancestral home at Bolsover where, before his exile he had erected a series of magnificent buildings from the designs of the architects Smithson, father and son. Notwithstanding these great works and the fact that he was in his 83rd year, in 1674 he commenced the erection of a new palace on the site of Nottingham Castle which is virtually the building used nowadays as the Art Gallery. It is an extremely interesting and instructive study to compare Wollaton, Bolsover and Nottingham and note the progress in architectural development during the century that these buildings cover.

Nottingham Castle was built from the Duke's own designs and was completed in 1679 by his son Henry Cavendish, the second Duke of Newcastle. The chief clerk-of-the-works was Marsh, Richard Neale was steward, and the total cost was £14,002 17s. 9d. The internal arrangements of rooms were different from those which obtain to-day and the principal rooms were on the first floor. One of the main entrances was by means of a double flight of external stairs on the East Terrace. This door was surmounted by a large equestrian statue of the first Duke, carved by that disappointing sculptor Sir William Wilson. Mutilated remains of this statue still remain to remind us of the fondness of the founder of the present Nottingham Castle for horsemanship.

I always find it interesting to remember that the building of Nottingham Castle was contemporary with Wren's building of St. Paul's Cathedral in London.

Nottingham Castle was the occasional residence of its noble owner from this time onwards, but in 1688 it offered asylum to the Princess Anne. Affairs had become so difficult in her father's court that at last she took the step of leaving it and her departure was almost the last straw and had not a little to do with James II.'s flight. She was handsomely lodged in rooms situate about where gallery A now is. She seems to have liked Nottingham so much that it is believed that she visited the place on several occasions after her accession to the throne.

In spite of the fact that in 1776 a grand ball was given in Nottingham Castle by the Earl of Lincoln to mark his appointment to the Colonelcy of the Nottingham Militia, the importance of the building gradually declined until finally in 1795 its great rooms and galleries were divided by walls and the whole building was let off in separate tenements. Amongst the various tenants were Miss Greaves whose Sedan Chair as late as 1825 bore her each week to Friar Lane Chapel and Miss Kirby whose elaborate breakfast and supper parties and generous and cheerful hospitality so much rejoiced the hearts of the bon-ton of Nottingham at the close of the 18th century.

About 1809 Lenton Road—"Park Passage" as it was called—was formed. It passes over the ancient ditch just near the Gatehouse and Stretton says that this ditch was filled to a depth of twenty feet. To rivet the south side of this wall, the 13th century wall of Henry III.'s time sustaining the east side of what is now the Castle Green was taken down, a bank was substituted, the moat disappeared and the stones of this wall used to form the wall on the south side of Lenton Road. It is interesting to bear in mind that considerable remains of the foundations of the walls of the medieval castle were found in 1924 when excavations were being made to provide the foundations for the Nurses' Home.

In 1831 the mansion was burnt by rioters amidst scenes of great tumult and disorder in the course of which much looting was carried out. It is stated that the costly tapestries of the castle were freely sold after these events by the rioters for 3/- per yard. Terrible damage was done and the whole place reduced to a mere shell. The Duke received £21,000 compensation for the outrage.

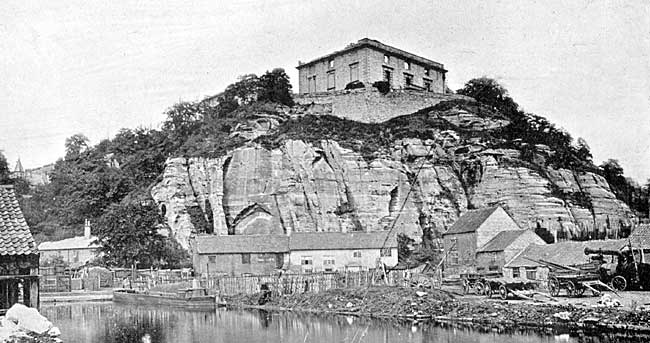

The ruins of Nottingham Castle, c.1870.

The castle remained derelict for forty years or so until finally it was let to the Corporation of Nottingham in 1875 on a 500 years' lease. Suitable alterations were made to the buildings and grounds and it was opened to the public on July 3rd, 1878, as a Museum of Fine Art.