< Previous | Contents | Next >

An itinerary of Nottingham

Cheapside and Long Row

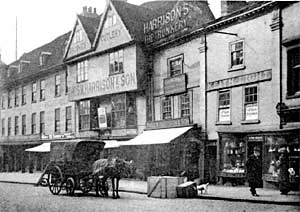

CHEAPSIDE.

Cheapside in 1912.

IT is no good crying over spilt milk or regretting that the march of progress has swept away the whole of this beautiful and interesting row. But it is impossible not to regret the passing of the beautiful old houses which formed Cheapside down to a few years ago. There was Babbington House with its gables, the delightful Georgian house occupied for so many years by Messrs. Thraves and there was also the last ancient bow-window shop in Nottingham situated upon this row.

Its name of Cheapside is not very ancient for it was called Rotten Row or Ratten Row in 1543 and appears to have changed its name to Cheapside some time in the 18th century. Cheapside was of course a most appropriate name, for "cheap" was the old name for barter, and Cheapside indeed formed a side of Nottingham Market Place Its continuation towards the west was Exchange Alley, that curious little thoroughfare which separated the shoe booths from the rest of the Exchange, and whose historical associations we have already seen.

LONG ROW.

Long Row in the 1930s.

Long Row is one of the oldest districts in the town as is shown by its lay-out. It consists of a number of very narrow sites fronting on to Long Row and extending to a great depth until they reached Parliament Street or the Back Side as it was anciently called. The sites were thus set out because of the great value of the frontage to Long Row and they were divided by paths many of which have come down to our own day in the form of those curious little passages which join Long Row with Parliament Street. In number one, now occupied by Messrs. Skinner & Rook, lived in the early days of the 19th century, Lord Lyndhyrst, who was at one time Lord Chancellor of England, and as we shall see he was not the only Lord Chancellor to live on Long Row. Not very far away is the Maypole Yard which commemorates the old Maypole Inn which was of such importance in the early part of last century when coaching was at its zenith. The Maypole had many coaches running from it, but seems to have specialised in coaches to Derby. It was in the Maypole Yard in 1825 that the tragedy took place whereby the "White Lady of Newstead" lost her life. This good lady's real name was Sophia Pyatt and in her old age she became an enthusiastic admirer of Byron. Nobody knows from whence she came or who were her connections, but for some years she spent the bulk of her time in pensive solitude amongst the gardens and ruins of Newstead Abbey. She was very deaf, and on September 21st, 1825, whilst on a visit to Nottingham she was knocked down and killed by a carrier's cart in the Maypole Yard, and to carry out her wishes her remains were interred in Hucknall Church as close as possible to the grave which held Lord Byron's remains.

The Black Boy Hotel in the 1930s. This Nottingham landmark was demolished amidst much public oppposition and replaced with a dull store in the 1960s.

The Black Boy Hotel is much modernised and its history, albeit associated to a certain extent with coaching, is not particularly fascinating, but in front of it, high up in a gable will be seen a modern statue representing Samuel Brunts, which reminds us that the land upon which it stands was part of the estate left for charitable use by this worthy when he died in 1711. He stated in his will that he wanted to benefit poor people in or near Mansfield, who "had been industrious and of sober life and conversation and feared the Lord." The estate which he vested in trustees has become extremely valuable so that the income from it is, I believe, over £6,000 per annum. There are some 250 pensioners receiving support from it each week while 300 scholars are receiving secondary education at Brunts' School, Mansfield, which is largely paid for by the charity. No. 17, which until a few years ago was noticeable because of the curious twisted columns which ornamented a window on the first floor and which were strangely reminiscent of the porch of St. Mary's at Oxford, was erected, I believe, about 1715 by Marshall Tallard. In it in 1793 lived Alderman Oldknow who was Mayor at the time and a riot took place in front of this house which is worth remembering as giving us some idea of the conditions under which our forefathers existed. It appears that a number of democrats who sympathised with the French Revolution had been permitted to drill in the fields of Nottingham, using dummy guns. This very much exercised the minds of the Tory party which felt that this drilling might be extremely dangerous, for the Jacobite troubles were still remembered and the horrors of the French Revolution were so close as to rouse suspicions where perhaps they were unjustified. At any rate the Tory mob attacked Oldknow's house, smashed his windows and generally damaged his property. As Alderman Oldknow was Mayor, one would have thought that he could have found sufficient protection in the police, but evidently that body was thoroughly inefficient. Alderman Old-know after threatening the crowd and after discharging a blank shot over their heads, shot off a blunderbus heavily charged with shot into the midst of the crowd, killing one man and severely wounding five others. This action effectually dispersed the mob, and it is interesting to find that Blackner in his History of Nottingham, published in 1815, not only commends the action of Alderman Oldknow in thus taking the law into his own hands, but claims as an inalienable right of all Englishmen the right to defend their own property even if it comes to killing people who may be presumed to be attacking it.

Lord Brougham lived in this house some time about 1820. He was Lord Chancellor of England and was associated with Mr. Denman, afterwards Lord Denman, as advocate for Queen Caroline in her celebrated trial. Finally Mr. Hind says that William and Mary Howitt, the Quaker poets, lived in this house for a short time, but I have never been able to find any confirmation of this fact.

In Greyhound Yard, which is named after the Greyhound Inn which has long since disappeared, took place a tragedy in 1808 when Mr. Joseph Hill was attacked and bitten by a dog. The wounds seemed to heal and Mr. Hill seemed no worse for his adventure for a time, but eventually the worst symptoms set in and hydrophobia developed and Mr. Hill died an agonising death. In reading old notices of Nottingham one is constantly reminded of the awful danger which was ever present in times past from mad dogs.

King Street and Queen Street (A Nicholson, 2001).

King Street and Queen Street represent that curious V-shaped slice of slum property which was called the "Condemned Area" and which was all swept away about the year 1888. It was a most unhygienic and immoral neighbourhood and nothing good could be said for it. It took about three years to clear and King Street was formed upon it and opened on June 22nd, 1892. But while clearing away so much that was undesirable, certain interesting features also disappeared; for example, the modern General Post Office stands on the site of Mellor's bell foundry where the fortune was made which was so nobly expended in founding the High School.

In Manning's Yard, which has also disappeared, lived Sandby the artist for some years, and Fennels Passage was so named from the Alderman Pennel who was sometime Mayor of Nottingham and was the architect of the original Exchange.

Another curious place that has disappeared is Crown Court which probably got its name from the Crown Inn which was a somewhat celebrated hostelry in times past and was a great rendezvous of the aristocracy. In 1815 there died in this court a certain Thomas Rippon who was a very curious character, but his chief claim to notoriety rested in the fact that he was a dwarf. He was only thirty-four inches in height, but in spite of his infirmity he was not only well-known but was highly respected. He lived to the advanced age of seventy-five and a few days before his death he ordered his own coffin to be made. This, according to his instructions, was to be six feet long and when it was brought home he got into it and laid down and expressed the highest satisfaction with it.