< Previous

FOR GOD’S SAKE LOOK WHERE HE’S GOING:

The London Road railway collision of 1879

By Stephen Best

There is a King, and a ruthless King,

Not a King of the poet’s dream;

But a tyrant fell, white slaves know well

And that ruthless King is Steam

E.P. Mead

An Anthology of Chartist Literature

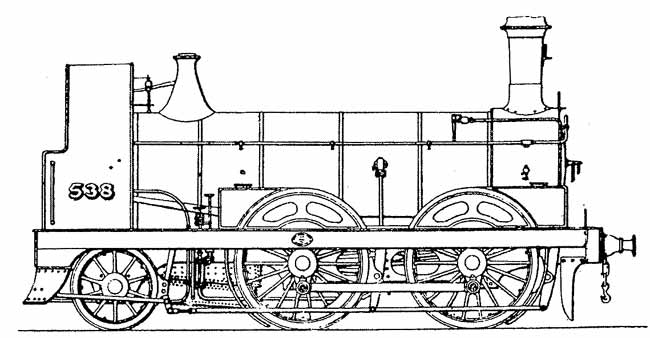

A Great Northern 0-4-2 engine, designed by Patrick Stirling. A locomotive of this type headed the 5.30 from Pinxton.

A Great Northern 0-4-2 engine, designed by Patrick Stirling. A locomotive of this type headed the 5.30 from Pinxton.

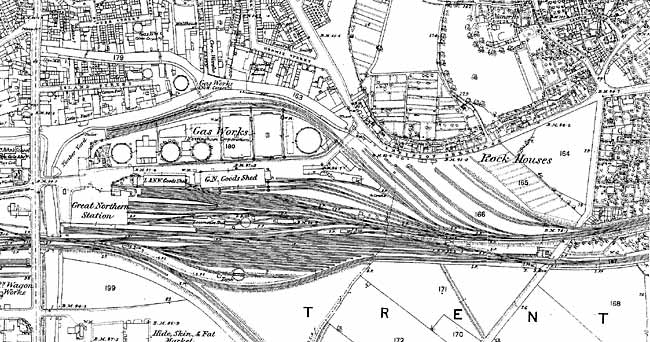

London Road Great Northern Station in 1881, showing its proximity to Sneinton.

The Old Coal-yard sidings, where the collision took place, lie south of the signal box in the middle of the map. There may have been alterations to the layout between the date of the accident and the publication of this map.

[Click on the map for a larger version suitable for printing]

In Sneinton Magazine no. 100 I mentioned several unfulfilled writing projects, saying, among other things, that I had never come across any instance of a railway accident occurring in, or close to Sneinton. Very recently, however, came the discovery that one had been staring me in the face for years, in the shape of a very brief entry in the Nottingham Date-Book. The following is the story which has been pieced together from this belated finding.

THE FIRST OF SEPTEMBER 1879 WAS something of a red-letter day for the Great Northern Railway in the Nottingham area.

Jointly with the London & North Western Railway, the Great Northern company had just built a line from Saxondale Junction, near Radcliffe-on-Trent, to Market Harborough. This would eventually join up with a Great Northern branch into Leicester, opening up a large area of east Leicestershire to rail traffic. It would also provide competition to the Midland Railway’s existing routes in the East Midlands.

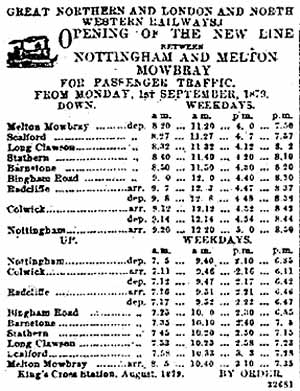

It was not found possible to complete all sections of the line at one and the same time, but a weekday service of four passenger trains in each direction between Nottingham London Road and Melton Mowbray was scheduled to begin on 1 September. Officials of the Great Northern, among them the staff at the station, were no doubt hoping for prominent newspaper headlines and some useful publicity. As things turned out, they received plenty of press coverage, but much of it was the opposite of what they were seeking.

The Nottingham Journal of 2 September did indeed print a brief report under the heading: THE NEW LINE BETWEEN NOTTINGHAM AND MELTON. This welcomed an important addition to the railway communication of the Midland district. The newspaper pointed out that although the only new stations served initially were Bingham Road, Barnstone, Stathern, Long Clawson and Scalford, it would in the near future be possible to reach Leicester by means of this line.

The Nottingham Daily Express of the same day considered that this was no unimportant addition to the railway communication of the Midland district, and paid tribute to the contractors, Benton and Woodhouse of Manchester, by whom, said the paper, considerable expedition has been manifested in pushing forward operations. Both newspapers displayed on their front pages a timetable for the new line.

In the ordinary course of events, the railway company would probably have been grateful for these modest expressions of approval, hoping they had caught the eye of prospective passengers in Nottingham. Unfortunately, however, the Great Northern, elsewhere in the Journal, also found itself the subject of a much lengthier news item topped by an arresting headline: ALARMING RAILWAY ACCIDENT AT NOTTINGHAM. TWENTY PERSONS INJURED.

Briefly, what had occurred was this. Just before half past six in the evening, the 5.30 passenger train from Pinxton, hauled by a 0-4-2 tender engine, was approaching the station, and was not far from the platforms when it struck a six-coupled goods engine standing in its path. In addition to the passengers referred to in the headline, several railwaymen were hurt. All those injured were eventually able to go home, or to their destinations, that evening.

Before we look at the press accounts of this mishap, a word is necessary about the layout of the Great Northern Station, better known to us today as London Road Low Level. Railway company rivalry in the Nottingham area had caused the Great Northern to lose the goodwill of the Midland Railway, and to be excluded from the latter company’s station in Station Street. This, a through station, would have been the ideal place for the companies to co-exist and cooperate, and infinitely more convenient for passengers, who could have changed from one company’s trains to another, without having to change, not only trains, but also stations.

As things fell out, however, the Great Northern had in the 1850s been obliged to construct its own terminus in Nottingham. Opened in 1857, this was reached via several miles of new track from Netherfield, running along the southern edge of Sneinton to London Road. Over the following decades the Great Northern developed several new routes in Nottinghamshire and nearby counties, but because its Nottingham station was a terminal one, all its trains, from whatever point of the compass, had to enter the station from the east. Although it was situated only yards beyond the old Sneinton parish boundary, the authorities never provided Sneinton with convenient and direct public road access to the station. Prospective passengers from here had to traipse along Pennyfoot Street and Fisher Gate to London Road, or to go via Evelyn Street and Poplar Street.

The lines approaching the station ran along the southern fringe of Sneinton on an embankment, crossing Meadow Lane by a bridge, and then descending to the level of the Great Northern goods yard and station. Sneinton had been part of the Borough of Nottingham only since 1877, and little or no building development had yet taken place along Colwick Road. A few large detached houses stood in gardens along Meadow Lane, but apart from these the dwellings nearest to the railway were in Sneinton Hermitage and the Lower Manvers Street and Poplar Street areas.

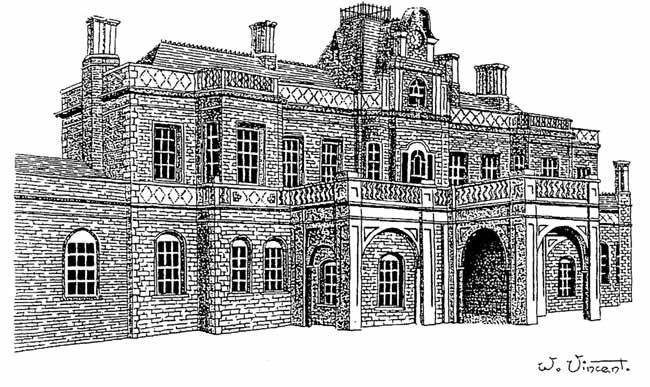

London Road Station: a drawing by Bill Vincent Reproduced by kind permission of the artist.

London Road Station: a drawing by Bill Vincent Reproduced by kind permission of the artist.In 1879 there were, in addition to the passenger station with its prominent overall roof, and a large goods yard with separate warehouses for G.N. and L.N.W.R. traffic, several sidings which stretched up towards Sneinton Hermitage. Here a fair amount of domestic coal was unloaded, and distributed by local coal merchants who maintained depots here. There were also long sidings leading to Eastcroft gasworks, immediately north of the station, on the north side of the canal. South of the running lines leading into the station were further sidings, known as the Old Coal Sidings or Old Coal-yard, and it is these which feature in this story.

So the scene is set. We shall see what four different newspapers had to say about the incident, and may be struck by how much their accounts varied from one another. According to the Journal of 2 September the accident took place at 6.24 p.m., not more than two hundred yards from the platform ends. Though originating from Pinxton, north-west of Nottingham, the train was, as we know, arriving at London Road from the east, having travelled in a huge curve around the north of town from Basford to Daybrook, Mapperley, Gedling and Colwick, before turning west towards Sneinton. Forty or fifty passengers were on board, and the speed of the train, as reported by this newspaper, was only about five miles an hour.

Tickets had already been collected at Colwick, and passengers were preparing to alight, when the engine collided with a light engine, which was about to be despatched to Colwick to fetch some trucks. The Pinxton train, asserted the paper, had somehow got into the wrong line - that seems palpable.

The Journal related that, in spite of the low speed at which the collision took place, the impact was violent. Most of those who suffered were in one of the third class carriages, and were chiefly labouring people from the country stations between Pinxton and Nottingham. No part of the train was derailed, however, and both locomotives remained on the rails.

Immediately following the crash, the station staff went to the spot in strong muster, and the passengers, who were in a considerable state of alarm, were assisted from the carriages. Most of the injuries consisted of cuts and bruises, while several other passengers, although exhibiting no outward evidence of damage, appeared severely shocked. Among these were two women. No one, however, had suffered any broken bones.

It was stated that the most serious injury was incurred by John Healey, a Great Northern district inspector, who was riding in the front brake van, next to the engine. He suffered a cut and bleeding head and nose inflicted by broken glass, but was able to walk into the station, from where he was conveyed to his home to Colwick.

Another railway employee to have come off badly was the badly stunned passenger train guard, William Lightfoot. The Journal understood, however, that the footplate crews of both engines had escaped without injury.

Going on sale as it did, several hours later than the Nottingham Journal, which was of course a morning paper, the rival Nottingham Evening Post had more time at its disposal to uncover human interest stories from the accident. Obeying the golden rule of naming as many local people as it possibly could, the Post went into greater detail, and varied in several respects from the Journal version of events.

Noting that the train had been arriving at London Road on time, the paper suggested that it was entering the station at a rather high speed - remember that the Journal had reported this as about five miles per hour. The Evening Post, however, was at pains to point out that for its story it was relying on the impressions of passengers and bystanders: the officials of the Company maintaining the utmost reserve about the matter. This, one feels, can have occasioned no surprise: any railwayman chatting to the press about the causes of a significant accident would have been in serious trouble with his employers. Having raised the question of the train’s speed, though, the Post immediately went some way to play down its importance, by observing that this was: now rendered comparatively safe owing to the great brake power with which the vehicles are supplied. As will be seen later, not everyone would agree with this confident opinion.

The Evening Post related that, just before it reached the outer end of the new platform on the southern side of the station, the train unexpectedly turned off on to the line serving the side of the station normally used by excursion trains. The signal at the point box was at ‘all clear,'’ asserted the newspaper, so that this part of the occurrence must be the subject of an official investigation...

Of the two engines involved, the stationary light engine was stated to have suffered nothing worse than broken buffers on its tender, but it was otherwise with the passenger engine. The machinery in the front and below the buffer was damaged materially, and when it came to a stand - which it did without leaving the rails - it was considerably ‘disguised’ as to its outward appearance.

The Post agreed that perhaps the worst injuries had been incurred by Mr Healey, whom it described as one of the railway’s permanent way inspectors. It reported how the shock of being thrown to the floor had damaged the back of his head, while broken glass had cut him severely. As if this were not bad enough, two of the poor man’s teeth had been broken in the collision.

A number of passengers had been hurt through being dashed against one another by the force of the impact. Among these were two Nottingham medical men: Mr John Varley, surgeon, of Burton Street, and Dr Beverley Robinson Morris, physician, of Regent Street. These two gentlemen were returning together from a professional engagement at Eastwood, sitting opposite each other in their compartment, Varley with his back to the engine. Morris afterwards related how he had just remarked that they would be at the platform in a moment, when: There was a sharp report very like the crack of a rifle, only much louder. The carnage immediately stopped with a great shock, and Dr Morris was thrown forward, shaken and having his leg bruised. He seemed to be rendered unconscious for a moment or two, but that quickly passed off, and he then saw Mr Varley lying on the opposite seat and in quite an unconscious state. It was some time before the latter came round, and when he did Dr Morris went to give what assistance he could to two others who were injured.

The Evening Post named some of these casualties as a Mr, Mrs and Miss Goddard of Colwick; and Mr Richard Gretton, plumber, gasfitter, painter and glazier, of Peas Hill Rise, with two other members of his family. The Goddards and Grettons were all sent home in cabs. George Gale Robinson, a grocer with a shop in Carrington Street, was badly shaken. The guard of the train, William Lightfoot, described in the Nottingham Journal account as severely stunned, was, according to the Post, also badly shaken.

One unidentified gentleman, aged about seventy, had been riding in a compartment with his son and daughter, and the two men were unlucky enough to be thrown forward against each other, violently cracking heads. The old man incurred a cut forehead, while the younger received a gashed eye. Evidently no one considered it worth finding out and printing the names of any of the labouring people from the country stations. Judging from the timing of the train, these seem most likely to have been men who lived in Nottingham, but were employed somewhere along the route from Pinxton, and were coming home after a day‘s work.

Advertisement in the Nottingham Daily Express of the day after the accident, giving details of the new train service to and from London Road.

Advertisement in the Nottingham Daily Express of the day after the accident, giving details of the new train service to and from London Road.Immediately after the crash two medical gentlemen were sent for: Dr H.O. Taylor of Castle Gate and Mr Buckoll, the Great Northern Railway’s local surgeon. They helped patch up the injured before they were moved. Like Buckoll, Dr Taylor would be quite familiar with railway injuries, as consulting surgeon to the Midland Railway in Nottingham. He was also the first official police surgeon in Nottingham Both doctors were closely associated with Sneinton. Herbert Owen Taylor was one of a well-known local medical family, several of whom were buried in the churchyard here. A gravestone inscription at Sneinton shows that he and his wife suffered the tragic experience of losing three one-day-old children: one in 1880 and twins two years later.

Edward Charles Buckoll lived and had his practice in Minerva Terrace, Sneinton Road within about six hundred yards of the collision site. In 1875 he had unsuccessfully stood as an Independent candidate for a place on the new Sneinton School Board. If Buckoll was at home when called out, he would have been able to reach the scene of the accident within a very few minutes.

There seems to be no indication of whether the noise of the collision was noticed in Sneinton, but some inhabitants of Sneinton Hermitage and Manvers Street lived only three hundred yards away, so might well have heard the loud report described by Dr Morris.

The Post had no hesitation in identifying the pointsman in charge of the signal box at the time of the accident as a man named Clarke, who had been put under examination as to his knowledge of the affair. (But read on for the full facts.) The paper was able to report that the track had been quite undamaged by the collision and that locomotives and rolling stock had been quickly removed from the scene.

In a postscript, the Evening Post noted that the Great Northern Railway’s superintendent had arrived on the spot at 11 p.m. the previous night. The prompt presence on the scene of such a senior officer would have indicated that the company was taking this comparatively minor accident very seriously. Some preliminary evidence had been taken about the crash, but no full inquiry had yet been started. There was good news about Mr Varley, whose injuries had been perhaps the worst of any farepaying passenger: he had passed a restless night, but was slightly improved by the morning.

This detailed account was in contrast to the coverage given by the Nottingham Daily Express, which that morning had been comparatively unconcerned about the whole affair. 'We learn that last evening an accident which might have proved very serious occurred on the Great Northern Railway close to this town. It seems from what we have been able to ascertain that a passenger train from Pinxton ran off a siding and came in collision with a tender. At first it was thought that several passengers had been seriously injured, but subsequently it was ascertained that this statement was incorrect, although the fact of the collision caused at the time considerable alarm and excitement. We further learn that the traffic was in no way impeded.

On the following day, 3 September, the Nottingham Journal was less confident of Mr Varley’s immediate recovery. He was, said the newspaper, far from being well. The report did, however, concede that none of the passengers had sustained a serious injury. It, too, mentioned that leading officials of the Great Northern company were in Nottingham to carry out their investigations.

That same morning, no lesser paper than The Times seemed to have had closer access to someone in the know, publishing a brief, but apparently fact-filled item on the collision: Mr Robinson, the assistant superintendent of the line, arrived in the town from London, and yesterday he inquired into the circumstances attending the accident, which, it appears, occurred through a mistake at the points. A short time before the collision a coal train arrived and was run into the coal yard at the back of the station. The engine was then detached and returned towards the points, about a quarter of a mile from the station, awaiting the passing of the passenger train from Pinxton to Nottingham before it was taken across to a siding. This train approached, and the signals not being against it, came on at a fair speed towards the station. The points man, however, after shunting the coal train into the coal yard, had neglected to alter the points so as to run the Pinxton train up to the passenger platform. The consequence was that it dashed violently into the stationary coal engine. The driver of the passenger train, seeing that a collision was inevitable, reversed his engine, jumped off, and escaped unhurt. The driver of the coal train also sprang to the ground and was uninjured, but the firemen of both the engines, whose names are Coulson and Elsam, remained at their posts, and were rather severely hurt...

A very interesting report appeared in the Nottingham Daily Express of 3 September, which now appeared anxious to make up for the insouciance of its item of the previous day. This time it headed its headline read: THE ALARMING RAILWAY ACCIDENT ON THE GREAT NORTHERN LINE NEAR NOTTINGHAM. One can only conclude that the Express had not troubled to send a reporter to the site before printing its earlier story, and subsequently found that its rivals had quite outshone it. A day later, therefore, it was at pains to inform readers that some people had indeed been rather seriously hurt.

This second Daily Express account gave the public several personal details not reported in the other papers. A third doctor, Mr Charles Vernon Taylor, had joined his brother and Mr Buckoll in attending to the injured. Like his brother, C.V. Taylor would within a few years put up a memorial in Sneinton churchyard to an infant child.

One of the injured, Richard Richmond of Peas Hill Road, had been badly bruised and cut about his face and body, and although he will not be able to resume his occupation at present, he is progressing as well as can be expected. Like Gretton, Richmond was a plumber, and actually lived, not in Peas Hill Road itself, but just round the comer in Brighton Street, which ran from Peas Hill Road to Dame Agnes Street. His close neighbours Mr and Mrs Gretton were reported as: still confined to their beds, although their condition has improved.

Mr Robinson of Carrington Street was progressing satisfactorily, but was yet unable to attend to his grocery business. A Mrs Timms of the Meadows had received bruises and other injuries, while Mr Varley, though unconscious during the night, was now considerably better. He was, however, much hurt about the head, and his medical attendants are of opinion that for the present his friends should not disturb him.

Here, then, were stories in four different newspapers describing the collision. The Nottingham public had been told that the passenger train had been entering London Road Station at about five miles an hour: or at a rather high speed: or at a fair speed. The point of collision was no more than two hundred yards from the station platforms: or it was about a quarter of mile from them. The four footplatemen all escaped injury: or only two of them did.

No doubt a trawl through other newspapers available in Nottingham in 1879 would reveal even more points of discrepancy (no pun is intended) between their various accounts. Each of the four papers quoted had differed from at least one of the others in some aspect of reporting the incident, while the Nottingham Daily Express had, as noted, achieved the added distinction of contradicting itself within the space of twenty-four hours.

It would take the inspecting officer of the Board of Trade’s Railway Department to set out the sequence of events clearly, fairly, and dispassionately. That gentleman was Major Francis Marindin, Royal Engineers, who succeeded in presenting his report on the collision to the Board on 5 September, only four days after the collision occurred.

Marindin would be back in Nottingham within a few months, as the inspecting officer for the new Midland Railway bridge over the Trent on another new line to Melton. This was the structure now known as Lady Bay road bridge. In between looking into the London Road collision and judging the fitness for traffic of the Trent bridge, Marindin would be one of the officers summoned to Scotland to examine the wreck of the fallen Tay Bridge at the end of December 1879.

His report on the London Road Station collision concisely restated the circumstances of the accident. As the Pinxton train came into Nottingham station: It was turned into the Old Coal-yard sidings, and came into collision with a goods engine which was standing on these sidings, waiting to come out.

The inspector gave the number of persons injured as twenty-five passengers and five railway servants. He added that the train guard and an inspector who was travelling in the train (Lightfoot and Healey) were too badly hurt to appear at his inquiry. His report confirmed that the passenger engine had received the greater damage: Leading buffer-beam, buffers, footplate, and fall-plate broken; framing end broken and bent; sand boxes and life guards broken. The tenders of both engines, together with two carriages, had also been knocked about. Considering that their bodywork was of wood, the carriages sustained less damage than might perhaps have been feared.

The signal box concerned in the movement of the two trains was 408 yards east of the platform ends, and the junction of the lines leading to the old and new platforms was 105 yards nearer to the station. The box contained 43 levers, which were fully interlocked. It was, therefore, theoretically impossible for a signalman to lower a signal for a train to pass until the points had been set in the proper direction. Nor could the signalman show signals which would lead to a collision between trains, or move any points affecting a line on which a train was travelling under clear signals. Significantly, however, the system of interlocking in use at this box was somewhat out of date, and installations of this pattern were no longer being made.

The first railwayman to give evidence to Major Marindin was Joseph Jeffs, who had worked in the Nottingham box for almost seven years. He told the inspector that he had been senior man on duty, with Signalman Clark, the man named by the press, working under him to Team the box.’ The goods train arrived from Boston just before six, and disposed of wagons in the Great Northern goods yard and the Old Coal-yard. At about 6.23 the goods engine returned tender-first to the signal, which allowed access to the Coal-yard, and was at danger.

The incoming Pinxton train went by his box under clear signals, travelling at its usual speed, about 10 to 12 miles an hour. As it passed, Clark cried out: ’For God’s sake look where he’s going,’ and Jeffs realised that the points were set for the Old Coal-yard. It was, he said, too late for him to do anything as the train was by then over the locking mechanism. He had, he said, not previously noticed that the point lever was over: T trusted to the locking mechanism,’ he told the inspector. After the collision he found that the point lever was over, and had asked the chief signal inspector how such a thing could be possible. Jeffs stated that he had known of interlocking hooks slipping, but not at these signals or points.

He believed that it was in his instructions to see that the road was right before setting the signals for a train, but did not know where that instruction was written down. Jeffs did, however, insist that it was not his duty to test the locking system: if anything was found to be out of order he sent for a fitter.

William Clark, who had already seen his name in the newspaper in connection with the accident, had been a signalman for three years, and had worked at the boxes at Netherfield Lane and Colwick North Junction before coming to London Road to learn the working of this bigger signal box. He corroborated Jeffs’s evidence, and had pulled off the signals for the passenger train, under the supervision of Jeffs. He had not observed that the points lever was also off ‘until the engine and half the train had passed the box. Had I had more experience in the box, I would probably have seen that the lever was over, and had no business to be over; but I did not feel quite at home in the box.’

In charge of the engine of the passenger train was Joseph Shotcliffe, had been a driver for four years, but on passenger trains for only a month or so. He deposed that as his train approached the station, all the signals were clear for him to run into the old platform. He passed the signal box at 8 or 10 miles an hour, and only noticed that the points were set for the Old Coal-yard when his engine wheels were almost on top of them. Steam was shut off, and Shotcliffe immediately reversed his engine. He did not, however, sound his whistle. The brake was already on, and his fireman was further tightening it up until the moment of impact.

Just before the collision occurred Shotcliffe jumped off his engine, escaping injury of any kind. He told the inspector that: ‘My engine, no. 46, is a four-wheel coupled tender engine. The only break [sic] is an ordinary hand-break, with one wooden block on each of the six tender wheels.’ This means, remember, that the engine itself had no brake at all acting upon it. The driver added that he had not seen the goods engine blocking his path until after he had put his own engine into reverse.

Shotcliffe’s fireman, Thomas Coulson, had been firing for ten months. He too had not noticed the position of the points until his engine was within a very few yards of them, whereupon: ‘I called out to my mate ‘Woa!’ Coulson’s hand was on the brake already, and he further tightened it, but did not think that speed had been much reduced below 10 miles an hour when they struck the light engine. He told Major Marindin: 'There was a considerable shock, and I was knocked against the face-plate of the fire-box, and somewhat hurt. I am quite fit for work again.'

George Atkin, the driver of the goods engine, had five years’ experience behind him. He described how his engine had reversed up to the signal, and had stood waiting to leave the siding for about seven minutes. He had sounded his whistle to remind the signalman he was waiting for the road. Atkin had not noticed the position of the points, and saw that the passenger train was on the wrong line only when it was within five or six yards of him. He had no time to get to the reversing lever, so, calling out to his fireman, he jumped off the footplate. It was Atkin’s opinion that the force of the collision had driven his own engine back about forty or fifty yards. He agreed with Shotcliffe and Coulson that the passenger train was still moving at 8 to 10 miles an hour when it struck, but said that it had been impossible for him to judge the speed exactly. Of his fireman he recalled; 'My mate stuck to the engine and was rather hurt.’

The inspector next interviewed William Huthwaite, who was stationed at Bottesford, and the fitter in charge of maintaining all the locking frames between Nottingham and Grantham. He stated that he generally visited each signal box once a fortnight, but always came to the Nottingham box every week. He would examine all the apparatus, and traffic permitting, would try out the interlocking, If anything was found broken he reported it to the inspector of signal fitters, but if something merely needed oiling, cleaning, or tightening, he did it himself He had last examined and oiled the signal frame al Nottingham on 30 August, just two days before the accident. Everything was in order, and Huthwaite thought he had spent a couple of hours at the box. He told Major Marindin that between 9 and 10 o’clock on the evening of the collision.

Inspector White had called him to the box, and ordered him to put a fresh interlocking hook on the defective locking bar. White told him that the lever had been slipped past the hook by the signalman.

The inspector of signal fitters, James White, told the inquiry that he was at home when the collision occurred. Having been called out, he went with two other Great Northern officials to the signal box. Here the signalman worked the levers and tried the locking, and it was found that a part of the interlocking was out of order. Going beneath the box and examining the frame, they discovered that an interlocking hook was out of place, so that it did not engage with the lever. The bolt was a little loose, and White considered that it had probably been knocked out of place by the lever having been put back violently. White concluded by stating that although he had known an interlocking hook broken, he could not remember one knocked out of place in this manner.

The last railway servant to be interviewed by Inspector Marindin was Amos Pigott, signal superintendent. He had been standing in the station when the accident happened and was immediately on the spot. After visiting the site of the collision, he went into the box. He told Jeffs to try the locking mechanism, and quickly discovered that the home signal for the main line platform could be lowered quite easily at the same time that the points were open for the Old Coal-yard. Going underneath the frame, he could see nothing amiss, but Inspector White found in his presence that the offending interlocking hook no longer prevented the signal from being pulled, and was loose at the bolt. He ended his evidence by stating that there were several frames of this type on the line, and that hooks often needed tightening up. He did not, though, remember any previous case of an accident arising from failure of a lock.

Having heard the accounts of all these railwaymen, Major Marindin came to his conclusions about the accident. He suited that the driver of the train from Pinxton had approached the station on time, under clear signals allowing him to enter the old platform line. After passing the signal box the driver saw that the points were set for the Old Coal-yard sidings, and although he immediately reversed his engine and applied the tender brake, he still struck the tender of the goods engine at a speed of about eight miles an hour.

The signalling apparatus should have rendered such a situation impossible, but part of the interlocking equipment was loose, and had failed to act. The inspector could not say how long before the accident this component had worked loose, or whether this was the result of violent or improper usage. He did, however, judge that the way they were fixed was such that they might easily become loose unless very carefully attended to.

Marindin had been told that signalling frames of this design did not seem to get out of order to an unusual extent, but it was a fact that none of this pattern were any longer manufactured, and that more reliable means of locking had been adopted.

He therefore came to the conclusion that the main cause of the collision was undoubtedly the failure of the interlocking apparatus, but still considered that the signalman Joseph Jeffs was not free from blame. Although there were no printed regulations to back this up, it was widely understood that signalmen should ensure, before pulling off a signal, that the line to which it applied was not obstructed. Had Jeffs looked more carefully at the frame in his box, he would have seen that a lever that ought to have been put back was still in the wrong position. He would still have had time to reset the points and avoid the collision.

Driver Shotcliffe of the passenger train also received a sharp word. He, said Marindin, seemed not to have been very prompt in his reactions, or more might have been done to avert the collision in the 100 yards before he hit the standing locomotive. Had he sounded his whistle, the guards' brakes in his train might have been applied, and the driver of the other engine might have begun to move it, so lessening the force of the impact.

These were, however, really side issues, and the inspector put in a nutshell the real cause of the Great Northern Station collision:

The lesson which this accident teaches is, that it is not safe for signalmen to trust to the interlocking apparatus under their control to be absolutely infallible.

Every machine, however perfect of its kind, is liable to get out of order, and although it is almost impossible to over-estimate the value of these modern inventions as safeguards against the mistakes arising from human fallibility, yet it is now no less necessary than it always has been for signalmen to exert the utmost vigilance, and to bring the whole of their attention to bear upon the working of the points and signals for which they were responsible.

Ail this was sound commonsense, and Signalman Jeffs himself had spoken the simple truth when he told the inspecting officer: 'I trusted to the locking mechanism.' The railway company itself, though, did not escape further criticism in Major Marindin's closing sentence. In conclusion, it should be observed that, had the driver had at his command proper continuous break., he might certainly have considerably mitigated the force of the collision, even if he had not been able to avert it altogether.

These final observations, of which printed copies were sent to the Great Northern Railway on 20 September, reflected a sentiment that would be repeated on many occasions over the years by officers of the Railway Inspectorate. While railwaymen could undoubtedly grow too confident in the infallibility of the safety precautions under which they worked, they frequently had to contend with inadequate equipment and modes of operating, when better ones existed. At London Road in 1879, even if some very humbly paid railway servants did not act as quickly as they might have done, they were working with an already obsolescent form of signalling installation, and with trains of insufficient brake power. In spite of what the Evening Post airily believed, the Great Northern used a far-from-ideal braking system.

The newspapers, as was their right and usual practice, had offered a mixture of conjecture and fact about this collision. Well respected local people had been passengers in the train, and the Nottingham public would eagerly have read about their experiences and, indeed, their injuries. William Clark, though, might with justice have felt that his name should not have been bandied about with so little regard for the facts: at no time during the incident had he been in charge of the signal box.

When the inspector’s report was made public later in the month, the Nottingham Journal summed up its findings very briefly, under the headline: CONTINUOUS BRAKE. It reported simply that the main cause of the accident had been a failure in the locking apparatus, and that better brakes might have enabled the driver to reduce the speed of the train, if not halt it. before impact. Significantly, the paper no longer mentioned the levelling of any criticism at ordinary railway servants. The company, not its men, was the real culprit. From the brevity of this news item one cannot help feeling that the collision was now stale news, and that Nottingham had lost interest in the story.

We end by returning to Major Marindin’s official report. In common with many others submitted by the Railway Inspectorate, the one on the London Road collision is a fascinating document. Although much of the evidence presented is necessarily rather technical and matter-of-fact, the human factor continually breaks through, Although no fatalities occurred in this accident, we are made to realize that, here on the edge of Sneinton, men going about their daily work were suddenly caught up in a moment of intense fear and considerable danger. Signalman Clark cries out 'For God’s sake look where he’s going/ Fireman Coulson calls 'Woa' to his mate, sticks to his post, suffers a considerable shock and is 'somewhat hurt? In spite of this, this modest man reports himself quite fit for duty after a day or two. Driver Atkin states that the force of the crash drives his own engine back forty yards or more, his fireman, still on the footplate, being ‘rather hurt?

And meanwhile, a quarter of a mile away on this late summer afternoon, people in innumerable Sneinton homes, oblivious of the minor drama being played out almost on their doorsteps, are sitting down to their evening meal.

POSTSCRIPT

The 1881 census was taken just over a year and a half after the collision. Examination of its Nottinghamshire returns has revealed where some of the central figures in the accident were living at this latter date, and whether they were still following their same occupations. Happily, most indications are that they had emerged reasonably intact.

Mr John Varley, the most severely hurt of the passengers, was sufficiently well, at the age of 67, to be still in medical practice in Burton Street. Dr B.R. Morris, who had shared a compartment with Varley, also remained active as a physician, at 9 Regent Street. Morris was now 61.

Several of the railwaymen concerned were based at Sneinton’s near neighbour Colwick, where the Great Northern Railway had in the 1870s laid out extensive sidings, locomotive shed and workshops. Streets of company houses were also built in what in 1885 would become the new ecclesiastical parish of Netherfield.

The two railwaymen reported as too badly hurt to attend Major Marindin’s inquiry were doing the same jobs as they had been in 1879. The inspector, John Healey, was now 41, and resident in Traffic Terrace, a row of G.N. staff houses right alongside the entrance to the locomotive sheds. Not far away, in Manvers Street (not to be confused with the Sneinton Manvers Street,) was the home of the guard William Lightfoot, thirteen years younger than Healey.

The young firemen of the two engines involved were apparently fully fit, too. Thomas Coulson, who had told the inquiry he was quite well enough for work only a day or two after the collision, had by 1881 reached the age of 24, and lived in Curzon Street, within a short walk of the sheds. Coulson was still firing, as was John Elsom, last heard of on the footplate of the light engine as the passenger train bore down on him. Although his driver reported that he had been hurt, Elsom had evidently not come to any serious harm. He was a neighbour of Lightfoot in Manvers Street.

Joseph Jeffs, the signalman who figured prominently in the incident, did not live in the railway settlement of Colwick. In 1881, and now aged 34, his house was in Brighton Street, where, strangely enough, one of the injured passengers, Richard Richmond, also lived, With Richard Gretton, another passenger casualty, residing close by in Peas Hill Rise, it is possible that the signalman was on nodding terms with these two men who had shared a traumatic event with him.

Joseph Shotcliffe, driver of the Pinxton train, did not appear anywhere in the Nottinghamshire returns for 1881. One can only conjecture whether he had transferred to another area, or had left railway service altogether. His failure to sound his engine whistle had been adversely commented on by Marindin, but it is extremely unlikely that this would have cost him his job. A very young railway fireman, whose name was written as James Shotliff, was living in 1881 in a Colwick lodging house; he may have been a relation.

George Atkin, driver of the goods engine, was another not listed at Colwick in the census returns. A railway engine driver bearing this name, however, was at this date resident in Kirke White Place, The Meadows. If this is indeed our man, one is tempted to wonder whether he. might have left the Great Northern sometime after the accident, and joined the rival Midland Railway, whose engine sheds in Middle Furlong Road were just around the comer from Kirke White Street, very close to Atkin’s home.

One final note: passenger trains from Pinxton had begun only in 1876, and continued to run into London Road Station until the opening of Nottingham Victoria in 1900. From that date onwards they terminated at the latter station. The Pinxton branch eventually lost its passenger service in January 1963.

It is possible that some readers may fed little sympathy for the railwaymen involved in this story. If so, they are invited to read Frank McKenna’s ‘The railway workers 1840-1970,’ (Faber, 1980.) Described by Jack Simmons, the great historian of the Victorian railway, as written ‘sometimes with indignation and compassion,’ this absorbing book makes one understand the working conditions that railway employees had to put up with, day in and day out. At the head of this piece I have taken the liberty of including the verse quoted at the beginning of McKenna’s book.

< Previous