< Previous

WITH GRASSY TREAD:

Further thoughts on Sneinton churchyard

By Stephen Best

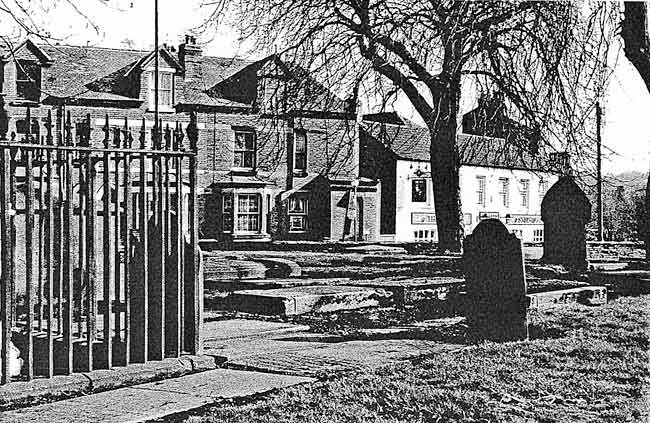

A view of the churchyard in the winter of 1991, showing the horse-chestnut which had to be felled in 2004. The railing in the foreground is part of the memorial to Thomas Martin.

A view of the churchyard in the winter of 1991, showing the horse-chestnut which had to be felled in 2004. The railing in the foreground is part of the memorial to Thomas Martin.‘The living come with grassy tread

To read the gravestones on the hill....'

(Robert Frost: In a Disused Graveyard)

DURING MORE THAN TWENTY years of writing about Sneinton certain topics have come to obsess me. Sometimes the imagination has been caught by an intriguing building, about which few facts are discoverable; or an historical figure of the locality, of whom one would like to find out more.

Another sort of obsession is the lost cause, or a cause that seems likely to be lost one day. London Road Low Level Station, discussed in the latest issue of Sneinton Magazine, is an example. Once it was hoped that it would become the city’s Industrial History Museum, but a change of mind by the council sadly signalled the end of that aspiration.

Also in this category, one particular bee in my bonnet is Sneinton churchyard, whose condition has long been a cause for concern. Situated in a fine position on Sneinton’s low hill, it is a major asset to the neighbourhood: a green open space dotted with mature trees, and a storehouse of memorial stones which uniquely illustrate the history of the neighbourhood. Add to this the presence of a splendid church, largely the work of Bodley and Hare, one of the country’s best firms of ecclesiastical architects at the beginning of the twentieth century. All this ought to be something that the community, both congregation and non-churchgoers, should hold dear, but somehow, something has frequently seemed missing in Sneinton’s attitude towards it.

I was about half way through writing this article when, in the late autumn of 2003, something happened to make the churchyard seem all the more relevant a subject for comment and concern. This is, therefore, a personal expression of unease, mixed with more than a dash of indignation. We have to begin, though, by sketching in a bit of the background.

During 1986 some members of Sneinton Environmental Society became anxious about the state of the churchyard, and with the enthusiastic backing of the then vicar, the Rev. John Tyson, set about trying to get this priceless heart of Sneinton tidied up and put in good order.

The Environmental Society offered financial support for this venture, and donations were also forthcoming from Nottingham Civic Society, Nottingham City Council, and the Diocese of Southwell.

A team from the Family First Project Agency arrived to rescue those headstones which were no longer in their proper places as grave markers. Many of these had, since the 1930s at least, lain flat on the ground, where they formed a sort of pavement. In this position they had been walked, cycled, and roller-skated over for more than half a century. It was decided that these should be fixed upright by iron cramps to the churchyard wall, where the possibility of further damage would be greatly reduced, and their inscriptions more easily readable.

Inevitably, the refurbishment of the churchyard had its teething troubles. In spite of these, however, all those headstones were reinstated whose correct locations were known. Others, while still in their right places, were toppling over, and had to be set up straight again. In addition, a very large amount of rubbish and masonry debris was cleared away, and we relaxed, believing that the churchyard was happily restored, and fit to be suitably appreciated as an historical focus of Sneinton, and one of its most important sites.

In an attempt to widen local interest in it, the churchyard has figured in a number of Sneinton Magazine pieces over the years, which tell the stories behind some of the more interesting memorials. (A list of these appears at the end of this article.) For some time a guide to the churchyard was under consideration, to be written by the present writer, and illustrated by the late John Severn, whose architectural and conservational expertise, always generously given, had been of vital importance during the churchyard clean-up. John’s untimely death put an end to this guide project for the foreseeable future.

More than once since the refurbishment there has been reason to feel disturbed by the apparent lack of care shown towards the churchyard by the community, and too many walks here have proved depressing. The living may have displayed interest in the disused New England burial ground described by Robert Frost, but it has sometimes seemed that hardly anybody gives a toss for Sneinton churchyard.

There have been times during the past couple of years when it has looked almost as unkempt and unappreciated as it has ever been. Not to mince words, it has been a mess; no sooner has one cartload of litter been cleared away, than another has taken its place.

The condition of the grass, too, has always been a problem. Much of it is in deep shade for most of the year; overshadowed on the north side by the church building in the winter, and throughout by trees in full leaf during the summer. A further displeasing impression is created by the muddy state of the turf on either side of the main path. Here, a closer look reveals tyre tracks left by vehicles which have churned the grass into mud. We shall return to this question later in the article.

Now for something worse. Since the tidy-up further headstones have been scratched or disfigured, while others have fallen foul of spray-painters. The churchyard Calvary commemorating Sneinton men who died in the Great War has not escaped the paint treatment; this is doubly regrettable, as its designer had stipulated that it should not be cleaned or scrubbed, but allowed to weather naturally. The war memorial has also lost its metal inscription plaques.

It is hard to know what can be done to counter the brainless minority who casually deface a churchyard, but people of every faith, or of none, should be able to see that if the heartland of one cherished belief is so little regarded, then all are threatened. If we cannot respect each other’s hallowed places, our community is in a sorry state.

Many stories, some of them no doubt fascinating, remain to be told about Sneinton churchyard memorials. John Kerkbee, who died in 1656, has the oldest gravestone to survive here. James Barnes was drowned in the Trent in 1874. Ann Elliott, buried here in 1868, had for many years been a servant to the Morley family of Sneinton Manor House.

Autumn mist in the churchyard 1992. The large memorial is that of the Rev. Edward Williams.

Autumn mist in the churchyard 1992. The large memorial is that of the Rev. Edward Williams.William Smith of Woolpack Lane erected many local buildings, including the Albion Chapel just down Sneinton Road from the church. William Woodward lived in the Nottingham Canal lock house at Trent Bridge, where he collected the company’s tolls. Thomas Hopkin, also 'of the Trent Bridge,' was surveyor and engineer to the Trent Navigation Co., and Wright C. Sissling was landlord of the Union Inn in London Road.

The churchyard in Autumn. The prominent tomb-chest marks the grave of the Rev. Edward Williams.

The churchyard in Autumn. The prominent tomb-chest marks the grave of the Rev. Edward Williams.

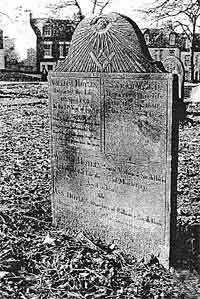

Mary Hopcroft’s gravestone, with a crowned and winged death’s-head.

The Hornbuckle family kept the Lord Nelson pub for several generations, and a group of three houses near the top of Sneinton Hollows still bears the name Hornbuckle Villas. Nathaniel Need and Caractacus D’Aubigny Shilton were prominent nineteenth-century residents of Notintone Place. William Winrow of Irongate Avenue (now Durham Avenue) made accordions, concertinas, and other musical instruments at his premises in Hollowstone. These and others have yet to be written about.

Gravestones commemorating people of no special wider interest can also have their value, for the way in which they exemplify variety in pattern and materials.

One very typical group of South Nottinghamshire headstones is made of Swithland slate, which provides a rich record for both historian and student of design. Unlike many other stones, slate weathers extremely well, and inscriptions cut in it retain their clarity, remaining almost as sharp as when new. To appreciate this fully, one has only to look at sandstone memorials in local churchyards and cemeteries. On these, even if the name of the person commemorated has survived, the detailed inscription is frequently worn away and illegible.

Slate, in contrast, is most durable. Although it can, through age and normal wear and tear, suffer minor flaking, chipping, and moss invasion, any more serious damage is usually the result of carelessness and vandalism. Slate headstones which have stood at Sneinton for over 200 years have lately been made unsightly by deliberate scratching, carving, and other defacement, and by wanton smashing with heavy objects.

This has sometimes happened when boys collecting conkers have thrown metal bars up into the horse-chestnuts. The falling conkers are of course accompanied by the bar, which can land willy-nilly on a valuable grave marker, damaging it irreparably. Quite apart from the aesthetic harm to the stone, it should not be forgotten that each one records a human life, and that the site is a consecrated one. Nor must it be overlooked that, although the churchyard has long been closed for burials, ashes are still interred here in a dedicated plot.

In the best account of the Nottinghamshire slate headstone, Maurice Barley identified the finest and most interesting early examples in the county.1 Although perhaps not possessing any stones which come into the very highest category, Sneinton can show sufficient examples to form a copy-book of a century or more of what may without exaggeration be considered a genuine, if minor, art form.

Just spend half an hour in the churchyard on a fine, warm summer day, and have a look at a few of these slate stones. Enjoy the delicate little fluted urns carved on the headstone of Rebecca Smith, wife of the wonderfully- named Daft Smith: the Gothic finial designs at the top of Jane Astill’s memorial: the charming spray of flowers and ears of com on the Bettney gravestone: and the intricate architectural composition, like an elaborate three-span bridge, carved above the name of Thomas Henderson.

Other architectural designs can be found on the stone in memory of William and Agnes Smith. Here the inscription is flanked by strange motifs; each of these looks like a fluted column topped by a ball, standing on a base featuring a tall two-light window.

Attractive decorations at the head of Eizabeth Barker's gravestone.

Attractive decorations at the head of Eizabeth Barker's gravestone.The headstone to William Hoyles and Sarah Ward displays striking Masonic symbols of square and compasses, and the all-seeing eye, while an earlier one commemorating Mary. Hopcraft (of another old Sneinton family) exhibits a terrifying winged and crowned death’s head. On Thomas Butler’s headstone is something resembling a giant stylized horseshoe: and Elizabeth Barker’s memorial stone has at its top what might be a lady’s fan, opened out to a full circle, and attached to a pretty ribbon. There are others equally worthy of examination.

Memorials made of different materials also warrant a close look. Thomas Martin’s chest tomb just east of the church has long lost its inscription, but part of its elegant iron railing survives; dating from the 1790s, it is embellished by pretty little urns. This must once have been a swagger piece of work, as befitted a rich man’s memorial. In the south-east comer of the churchyard, a High Victorian Gothic tomb chest - also long bereft of its identifying inscription - marks, I think, the grave of Arthur Morley, last of the great hosiery manufacturing firm of I. & R. Morley to live at Sneinton Manor House. His funeral in 1860 was witnessed by some four thousand people.

Thomas Henderson’s headstone features decorative architectural motifs.

Thomas Henderson’s headstone features decorative architectural motifs.

Masonic symbols adorn the Hoyles/Ward gravestone.

Like many others in the churchyard, this memorial bears the name of its maker, in this case J.E. Hall. A prominent builder and contractor in Victorian Nottingham, James Ebrank Hall’s business premises were at Carrington Street Bridge. His home was for some years in Sneinton: first in Belvoir Terrace, just across the road from the churchyard, and later in what was then the even more rural Colwick Road.

Go and see them all while you can. Remember, whenever a monumental inscription is broken, defaced or erased, it is lost for ever, and with it goes a little of our local heritage. Whenever a work of art, however minor, is lost through neglect or vandalism, we are all the poorer for it. When anyone gratuitously breaks the branches of a mature tree, one of the oldest living things in the neighbourhood is needlessly threatened.

All of this may sound like the outpourings of a Cassandra, crying ‘Doom, doom!’ Indeed, I cannot pretend that this is a specially optimistic article, but it was the fate of Cassandra to be ignored, and, frankly, fresh solutions for safeguarding the future of the churchyard are not easy to find. One thing, however, seems likely. Unless the community of Sneinton at large, not just the St Stephen’s congregation, remains alert to the problems which beset the churchyard, future generations will be left to shake their heads and wonder how Sneinton let slip one of its finest features. Already it is possible to imagine official voices arguing that what the church really needs is a car park, and that no-one really wants the trouble of the upkeep of this awkward expanse of muddy grass.

This was just about as far as I had reached in writing this piece when, late last year, an additional reason for disquiet forced itself to the forefront. For a number of years Nottingham City Council has been responsible for routine care of the trees and grass in the churchyard, and one recognizes that a busy local authority has many other claims on its time and resources. It has, however, sometimes been hard to escape the feeling that the council regards the grass, not as an asset to be kept in good, manageable condition by sensitive trimming, but as a nuisance to be suppressed as severely as possible.

Local anxiety upon this point had been reflected in a letter to the Autumn 2003 Sneinton Magazine. In it James White pointed out in exemplary detail how far this treatment differed from the recommendations set out in the Churchyard Handbook. He warned that large chunks of turf were being sliced from the uneven surface of the churchyard through the use of a ride-on mower in both dry and wet weather. Not only this, but he expressed the fear that very old shallow burials might be disturbed by over-vigorous use of heavy machines. The concerns of Sneinton people had, he reported, been passed on to the council and the P.C.C.

What, then, was the response of Nottingham City Council to this? A lighter, more delicate approach to the maintenance of the churchyard? If only that had been so. During the last week of November 2003 council workers set about removing fallen leaves, of which there are, admittedly, a great many every autumn. Following a prolonged period of torrential rain, someone in charge decided to clear the piles of leaves by using a mechanical shovel mounted on a tractor. Anxious onlookers watched (some from passing buses) as this operation proceeded, and the results were plain for all to see.

The grass looked in places as though a military exercise had taken place in the churchyard; one member of the congregation went so far as to liken it to the Somme. Ugly scars circled the church where the machines had run. It seemed at the time that the grass might need special restorative treatment, and indeed it yet may. Although, in spring 2004, much of it appears superficially in reasonable condition, closer inspection reveals that in very many places the green surface is composed of shallow-rooting weeds, which have sprung up where the grass was skimmed off too harshly.

There is also the very real worry that the weight of heavy vehicles has caused surface subsidence above the brick-lined burial vaults, of which there are a number in the churchyard. Not to be overlooked, either, is the danger posed to gravestones by such heavy machinery threading between them; even a glancing blow to a memorial is likely to inflict serious damage. A curious result of this scalping treatment is worth mentioning: one gravestone which had been sunk beneath ground level actually reappeared above the surface during the process.

It did also seem a pity that those who so sedulously scraped up every fallen leaf, even to the detriment of the grass, could not have also cleared away the other rubbish that disfigured the churchyard. Blue plastic crates: rolls of carpet: bits of upholstery: glass: plastic bottles and bags - all these were left behind by the leafremoval team. The blame for the presence of such junk lies, of course, entirely with the antisocial minority who dump it here. (It is only fair to record that this kind of refuse is disposed of through regular visits from hard-working council staff, some of whom have expressed dismay at the condition in which they found the churchyard.)

This writer, with others, has muttered for years about the dangers to Sneinton churchyard, pointing out the need for vigilance in the face of hooliganism and neglect. Last year’s bungled leaf clearance, however, suggests that we have to be on guard against a further threat. One hesitates to describe what happened in November 2003 as official vandalism, but the action taken was, at the least, highly insensitive. It would be interesting to know if Sneinton was singled out for such inappropriate treatment, or whether unsightly tyre marks similarly marred the grass at the Castle, Wollaton Park, and the Arboretum.

It was felt by many that the City Council let Sneinton down over this affair, and that it must do better in future if its green credentials are not to be scoffed at. As argued earlier in this article, the churchyard is not only a haven in the middle of a built-up district, but a repository of its local history and heritage. If those entrusted with its care cannot be relied upon to nurture it, we shall find it increasingly hard to persuade the general public that it is a place to be cherished.

The editor of this magazine wrote to the appropriate council department to complain about the above events, and received in reply, not a written answer, but a telephone call. He was told that the authorities have now agreed not to bring heavy machinery into the churchyard in wet weather, but that they justify its use on the grounds of economy of manpower. This is by no means a reassuring message - not everyone will agree on a precise definition of wet weather, and it is surely self- evident that tractors can damage memorial stones just as severely in dry conditions as in wet. Future autumns are awaited here with apprehension.

In returning to the subject of churned-up mud at the sides of the churchyard path, I run the risk of upsetting some acquaintances. It would, however, surely help matters if churchgoers and others with business at St Stephen’s could keep to a minimum the parking of cars in the churchyard. Of course, those physically disadvantaged in any way, or carrying heavy loads, have to drive their vehicles close to the building. Almost everyone who does so, however, is obliged to reverse on to the grass before leaving by the paved paths, so adding a further contribution to the unsightly muddy mess. The church path presents an increasingly ugly appearance, looking more and more like a motor access drive. Its lack of charm has been emphasized recently as a result of the writing incised by hooligans in the wet concrete after resurfacing.

Nobody should conclude that Sneinton is indifferent to the condition of its churchyard - or, indeed, to its real nature and function. But if everyone takes in a car as a matter of course, what hope is there of persuading others to respect it for what it is? And that, emphatically, is not a car park. There is, after all, a car park close by in Windmill Lane, which many, though not all, could use without undue hardship. The authorities must never be given an excuse to look for a way of turning a labour-intensive and awkward area of grass, trees, and gravestones into an expanse of asphalt for the sake of mere convenience.

Make no mistake, such things have happened elsewhere. Just because locations like Sneinton churchyard are ecologically and culturally important to a vocal minority like the Environmental Society, we run the risk of being tempted into believing that they are safe for ever. But unless people kick up a row when councils and residents fail to look after them properly, we face an unacceptable outcome. Remember the nightmare scenario sung about by Joni Mitchell in Big Yellow Taxi more than thirty years ago - her words remain just as relevant today:

They took all the trees,

Put ’em in a tree museum,

And they charged the people

A dollar and a half just to see ’em.

Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you’ve got

Till it’s gone.

They paved Paradise

And put up a parking lot.

The loss of a valued tree is no mere abstract anxiety, nor is it necessarily the result of vandalism. In recent weeks one of the magnificent horse-chestnuts by the churchyard wall, nearly opposite the Fox pub, had to be felled. This was the result of disease first noticed some time ago, and no one is to blame. It is hoped that the tree will be replaced, but one wonders how much chance any replacement will have of being allowed to grow without being vandalised. It is also a sobering thought that, even if all goes well with a new tree, it will be several generations before this comer of the churchyard looks the same again.

At about the same time as the horse-chestnut was cut down, a very large and heavy branch fell from a mature ash tree on the south side of the church, accompanied by lesser boughs. It is understood that natural decay caused this mishap, too. The only lucky feature of this accident was that the branches narrowly missed the noteworthy Henderson headstone, mentioned earlier in this article. Even so, the falling wood caused further damage to an already cracked flat gravestone next to it.

Such unhappy events serve as a reminder that our trees have enough natural hazards to contend with, quite apart from the additional intervention of destructive humans. We need to remain doubly watchful.

Earlier in this article I recommended readers to go and see the gravestones while they can. It may, however, already be too late, as by the time this appears in print the churchyard gates may have been locked against the public. Just as I finish, a notice is displayed on the gates, asking for public comment on a proposal to do this. There could be no more futile course of action than to lock the churchyard. Quite apart from being a gesture of hopelessness, of defeat even, it would be a discourteous act, whatever its legal validity. And, of course, it would solve nothing.

The churchyard should be a natural focus of Sneinton’s identity, and a place where something of the history of the community can be felt. In order to achieve this people have to be able to visit it, become familiar with it, and value it. To erect a barrier between it and the community will diminish its place in the heart of the neighbourhood. It was not to create an inaccessible place that Sneinton Environmental Society and Nottingham Civic Society put up money for the 1980s restoration.

What a message a locked churchyard will give to Sneinton: ‘Here is the historical centre of your community, but it is barred to ordinary law-abiding citizens.’ And while the harmless visitor and the reflective walker will find themselves excluded, the trouble-maker and the vandal will easily climb in and indulge in their malpractices, safe in the knowledge that they will not be disturbed by legitimate passers-by. They will indeed be very glad to have the place to themselves if people like me can no longer get in.

The following, whose memorials are in the churchyard, have been written about in previous issues of Sneinton Magazine. Some of the stones are easy to find and to read, while others may elude all but the most determined searcher. A look at the relevant articles, listed below, should prove helpful in locating gravestones in this latter category.

Thomas Henry BUTLER of Belvoir Terrace: son of the master of Nottingham Free Grammar School, d. 1858

no. 30, Spring 1989

Daniel FINN of Gridlesmith Gate (Pelham Street): tailor, d. 1802

no. 31, Summer 1989

William FRUDD of High Pavement: dancing master, d. 1791

no. 31, Summer 1989

Richard GOULD: farrier, d. 1802

no. 30, Spring 1989

George GREEN of Belvoir Hill and Notintone Place : mathematician and physicist, d. 1841

Passim

Joseph LOWE of Highfield House: draper, and Mayor of Nottingham, d 1810 (and others of his family)

no. 62, Spring 1996-7

Thomas MARTIN of Castle Gate: merchant hosier, d. 1795

no. 43, Summer 1992

Arthur MORLEY of Sneinton Manor House: hosiery manufacturer, d. 1860

no. 76, Autumn 2000

James SKINNER of Pierrepont Street: old soldier, and beerhouse keeper, d. 1872

no. 68, Autumn 1998

Thomas STEVENSON of Dale Street: blacksmith, d. 1886

no. 30, Spring 1989

William and Ann TOMLIN of Belvoir Hill: brother-in-law and sister of George Green, d. 1880

no. 30, Spring 1989

John WAINMAN of Portland Place, Walker Street: juvenile offender, d. 1881

no. 40, Autumn 1991

Rev. Edward WILLIAMS: Unitarian minister, d. 1787

no. 31, Summer 1989

General WOLFE of Island Street and Hermit Street: wharfinger, coal dealer, and publican, d. 1849

no. 68, Autumn 1998

Rev. Dr. Robert WOOD of Mansfield: former assistant curate of Sneinton, master of Nottingham Free Grammar School, chaplain to Nottingham Gaol, and vicar of Cropwell Bishop and Wysall. d. 1839

no. 30, Spring 1989

Mary Ann, Diana, and Mary Anne WRIGHT: first three wives of Christopher Norton Wright of Chapel Bar, Long Row East, Lister Gate, and Addison Street: stationer, publisher, and printer, d. 1813, 1823, and 1837

nos. 20 & 21, Spring & Summer 1986

John Hose read this article in proof, and visited the churchyard with me to assess its present state. I am very grateful to have enjoyed the benefit of his specialist knowledge. All unattributed opinions expressed in this article are my own, and do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Sneinton Environmental Society, or the editor of Sneinton Magazine. I am of course solely responsible for any errors.

FOOTNOTE: 24 May 2004. BBC East Midlands News on CEEFAX reported that officials in Mansfield had apologised after a mechanical digger damaged a number of graves in the town’s cemetery. The digger hit a number of graves, compressing the grass and leaving ridges on the surface. A councillor said that repair work had been carried out on the grass, and steps taken to ensure that the incident would not be repeated.

1. 'Slate headstones in Nottinghamshire.' Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire, v. 52, 1948

< Previous